Photoionization Spectroscopy O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vibrational-Rotational Spectroscopy ( )

Vibrational-Rotational Spectroscopy Vibrational-Rotational Spectrum of Heteronuclear Diatomic Absorption of mid-infrared light (~300-4000 cm-1): • Molecules can change vibrational and rotational states • Typically at room temperature, only ground vibrational state populated but several rotational levels may be populated. • Treating as harmonic oscillator and rigid rotor: subject to selection rules ∆v = ±1 and ∆J = ±1 EEEfield=∆ vib +∆ rot =ω =−EEfi = EvJEvJ()′,, ′ −( ′′ ′′ ) ω 11 vvvBJJvvBJJ==00()′′′′′′′′′ +++−++()11() () + 2πc 22 At room temperature, typically v=0′′ and ∆v = +1: ′ ′ ′′ ′′ vv=+0 BJJ() +−11 JJ( +) Now, since higher lying rotational levels can be populated, we can have: ∆=+J 1 JJ′′′=+1 vv= ++21 BJ( ′′ ) R − branch 0 P− branch ∆=−J 1 JJ′′′=−1 vv=−0 2 BJ′′ J’=4 J’=3 J’=1 v’=1 J’=0 P branch Q branch J’’=3 12B J’’=2 6B J’’=1 2B v’’=0 J’’=0 EJ” =0 2B 2B 4B 2B 2B 2B -6B -4B -2B +2B +4B +8B ν ν 0 By measuring absorption splittings, we can get B . From that, the bond length! In polyatomics, we can also have a Q branch, where ∆J0= and all transitions lie at ν=ν0 . This transition is allowed for perpendicular bands: ∂µ ∂q ⊥ to molecular symmetry axis. Intensity of Vibrational-Rotational Transitions There is generally no thermal population in upper (final) state (v’,J’) so intensity should scale as population of lower J state (J”). ∆=NNvJNvJ(,′ ′′′′′′′ ) − (, ) ≈ NJ ( ) NJ()′′∝− gJ ()exp( ′′ EJ′′ / kT ) =+()21exp(J′′ −hcBJ ′′() J ′′ + 1/) kT 5.33 Lecture Notes: Vibrational-Rotational Spectroscopy Page 2 Rotational Populations at Room Temperature for B = 5 cm-1 gJ'' thermal population NJ'' 0 5 10 15 20 Rotational Quantum Number J'' So, the vibrational-rotational spectrum should look like equally spaced lines about ν 0 with sidebands peaked at J’’>0. -

Optical Spectroscopy - Processes Monitored UV/ Fluorescence/ IR/ Raman/ Circular Dichroism

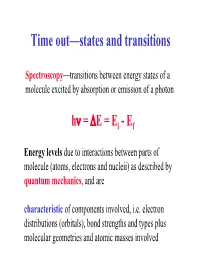

Time out—states and transitions Spectroscopy—transitions between energy states of a molecule excited by absorption or emission of a photon hν = ∆E = Ei -Ef Energy levels due to interactions between parts of molecule (atoms, electrons and nucleii) as described by quantum mechanics, and are characteristic of components involved, i.e. electron distributions (orbitals), bond strengths and types plus molecular geometries and atomic masses involved Spectroscopic Regions Typical wavelength Approximate energy Spectroscopic region Techniques and Applications (cm) (kcal mole-1) -11 8 10 3 x 10 γ-ray MÖssbauer 10-8 3 x 105 X-ray x-ray diffraction, scattering 10-5 3 x 102 Vacuum UV Electronic Spectra 3 x 10-5 102 Near UV Electronic Spectra 6 x 10-5 5 x 103 Visible Electronic Spectra 10-3 3 x 100 IR Vibrational Spectra 10-2 3 x 10-1 Far IR Vibrational Spectra 10-1 3 x 10-2 Microwave Rotational Spectra 100 3 x 10-3 Microwave Electron paramagnetic resonance 10 3 x 10-4 Radio frequency Nuclear magnetic resonance Adapted from Table 7-1; Biophysical Chemistry, Part II by Cantor and Schimmel Spectroscopic Process • Molecules contain distribution of charges (electrons and nuclei, charges from protons) and spins which is dynamically changed when molecule is exposed to light •In a spectroscopic experiment, light is used to probe a sample. What we seek to understand is: – the RATE at which the molecule responds to this perturbation (this is the response or spectral intensity) – why only certain wavelengths cause changes (this is the spectrum, the wavelength dependence of the response) – the process by which the molecule alters the radiation that emerges from the sample (absorption, scattering, fluorescence, photochemistry, etc.) so we can detect it These tell us about molecular identity, structure, mechanisms and analytical concentrations Magnetic Resonance—different course • Long wavelength radiowaves are of low energy that is sufficient to ‘flip’ the spin of nuclei in a magnetic field (NMR). -

Rotational Spectroscopy and Interstellar Molecules

Volume -5, Issue-2, April 2015 » Plescia, J. B., and Cintala M. J. (2012), Impact melt Rotational Spectroscopy and Interstellar in small lunar highland craters, J. Geophys. Res., 117, Molecules E00H12,doi:10.1029/2011JE003941 » Plescia J.B. and Spudis P.D. (2014) Impact melt flows at The fact that life exists on Earth is no secret. However, Lowell crater, Planetary and Space Science, 103, 219- understanding the origin of life, its evolution, and the fu- 227 ture of life on Earth remain interesting issues to be ad- » Shkuratov, Y.,Kaydash, V.,Videen, G. (2012)The lunar dressed. That the regions between stars contain by far the crater Giordano Bruno as seen with optical roughness largest reservoir of chemically-bonded matter in nature imagery, Icarus, 218(1), 525-533 obviously demonstrates the importance of chemistry in » Smrekar S. and Pieters C.M. (1985) Near-infrared spec- the interstellar space. The unique detection of over 200 troscopy of probable impact melt from three large lunar different interstellar molecules largely via their rotational highland craters, Icarus, 63, 442-452 spectra has laid to rest the popular perception that the » Srivastava, N., Kumar, D., Gupta, R. P., 2013. Young vastness of space is an empty vacuum dotted with stars, viscous flows in the Lowell crater of Orientale basin, planets, black holes, and other celestial formations. As- Moon: Impact melts or volcanic eruptions? Planetary trochemistry comprises observations, theory and experi- and Space Science, 87, 37-45. ments aimed at understanding the formation of molecules » Stopar J. D., Hawke B. R., Robinson M. S., DeneviB.W., and matter in the Universe i.e. -

Rotational Spectroscopy

Applied Spectroscopy Rotational Spectroscopy Recommended Reading: 1. Banwell and McCash: Chapter 2 2. Atkins: Chapter 16, sections 4 - 8 Aims In this section you will be introduced to 1) Rotational Energy Levels (term values) for diatomic molecules and linear polyatomic molecules 2) The rigid rotor approximation 3) The effects of centrifugal distortion on the energy levels 4) The Principle Moments of Inertia of a molecule. 5) Definitions of symmetric , spherical and asymmetric top molecules. 6) Experimental methods for measuring the pure rotational spectrum of a molecule Microwave Spectroscopy - Rotation of Molecules Microwave Spectroscopy is concerned with transitions between rotational energy levels in molecules. Definition d Electric Dipole: p = q.d +q -q p H Most heteronuclear molecules possess Cl a permanent dipole moment -q +q e.g HCl, NO, CO, H2O... p Molecules can interact with electromagnetic radiation, absorbing or emitting a photon of frequency ω, if they possess an electric dipole moment p, oscillating at the same frequency Gross Selection Rule: A molecule has a rotational spectrum only if it has a permanent dipole moment. Rotating molecule _ _ + + t _ + _ + dipole momentp dipole Homonuclear molecules (e.g. O2, H2, Cl2, Br2…. do not have a permanent dipole moment and therefore do not have a microwave spectrum! General features of rotating systems m Linear velocity v angular velocity v = distance ω = radians O r time time v = ω × r Moment of Inertia I = mr2. A molecule can have three different moments of inertia IA, IB and IC about orthogonal axes a, b and c. 2 I = ∑miri i R Note how ri is defined, it is the perpendicular distance from axis of rotation ri Rigid Diatomic Rotors ro IB = Ic, and IA = 0. -

Hydrogen Conversion in Nanocages

Review Hydrogen Conversion in Nanocages Ernest Ilisca Laboratoire Matériaux et Phénomènes Quantiques, Université de Paris, CNRS, F-75013 Paris, France; [email protected] Abstract: Hydrogen molecules exist in the form of two distinct isomers that can be interconverted by physical catalysis. These ortho and para forms have different thermodynamical properties. Over the last century, the catalysts developed to convert hydrogen from one form to another, in laboratories and industries, were magnetic and the interpretations relied on magnetic dipolar interactions. The variety concentration of a sample and the conversion rates induced by a catalytic action were mostly measured by thermal methods related to the diffusion of the o-p reaction heat. At the turning of the new century, the nature of the studied catalysts and the type of measures and motivations completely changed. Catalysts investigated now are non-magnetic and new spectroscopic measurements have been developed. After a fast survey of the past studies, the review details the spectroscopic methods, emphasizing their originalities, performances and refinements: how Infra-Red measurements charac- terize the catalytic sites and follow the conversion in real-time, Ultra-Violet irradiations explore the electronic nature of the reaction and hyper-frequencies driving the nuclear spins. The new catalysts, metallic or insulating, are detailed to display the operating electronic structure. New electromagnetic mechanisms, involving energy and momenta transfers, are discovered providing a classification frame for the newly observed reactions. Keywords: molecular spectroscopy; nanocages; electronic excitations; nuclear magnetism Citation: Ilisca, E. Hydrogen Conversion in Nanocages. Hydrogen The intertwining of quantum, spectroscopic and thermodynamical properties of the 2021, 2, 160–206. -

Rotational Spectroscopy

Rotational spectroscopy - Involve transitions between rotational states of the molecules (gaseous state!) - Energy difference between rotational levels of molecules has the same order of magnitude with microwave energy - Rotational spectroscopy is called pure rotational spectroscopy, to distinguish it from roto-vibrational spectroscopy (the molecule changes its state of vibration and rotation simultaneously) and vibronic spectroscopy (the molecule changes its electronic state and vibrational state simultaneously) Molecules do not rotate around an arbitrary axis! Generally, the rotation is around the mass center of the molecule. The rotational axis must allow the conservation of M R α pα const kinetic angular momentum. α Rotational spectroscopy Rotation of diatomic molecule - Classical description Diatomic molecule = a system formed by 2 different masses linked together with a rigid connector (rigid rotor = the bond length is assumed to be fixed!). The system rotation around the mass center is equivalent with the rotation of a particle with the mass μ (reduced mass) around the center of mass. 2 2 2 2 m1m2 2 The moment of inertia: I miri m1r1 m2r2 R R i m1 m2 Moment of inertia (I) is the rotational equivalent of mass (m). Angular velocity () is the equivalent of linear velocity (v). Er → rotational kinetic energy L = I → angular momentum mv 2 p2 Iω2 L2 E E c 2 2m r 2 2I Quantum rotation: The diatomic rigid rotor The rigid rotor represents the quantum mechanical “particle on a sphere” problem: Rotational energy is purely -

Fine-And Hyperfine-Structure Effects in Molecular Photoionization: I

Fine- and hyperfine-structure effects in molecular photoionization: I. General theory and direct photoionization Matthias Germann1 and Stefan Willitsch1, a) Department of Chemistry, University of Basel, Klingelbergstrasse 80, 4056 Basel, Switzerland (Dated: 2 October 2018) We develop a model for predicting fine- and hyperfine intensities in the direct photoionization of molecules based on the separability of electron and nuclear spin states from vibrational-electronic states. Using spherical tensor algebra, we derive highly symmetrized forms of the squared photoionization dipole matrix elements from which which we derive the salient selection and propensity rules for fine- and hyperfine resolved photoionizing transitions. Our theoretical results are validated by the analysis of the fine-structure resolved photoelectron spectrum of O2 (reported by H. Palm and F. Merkt, Phys. Rev. Lett. 81, 1385 (1998)) and are used for predicting hyperfine populations of molecular ions produced by photoionization. I. INTRODUCTION dynamics.19–21 Thus, there is a growing need for theo- retical models capable of describing fine- and hyperfine Photoionization and photoelectron spectroscopy are effects in molecular photoionization. Whereas the hy- among the eminent experimental techniques to gain infor- perfine structure in Rydberg spectra has previously been mation on the electronic structure of molecules, on their treated within the framework of multichannel quantum- 14–18 photoionization dynamics and the structure and dynam- defect theory (MQDT), we are not aware of -

INTRODUCTORY LECTURE on ROTATIONAL SPECTROSCOPY

INTRODUCTORYINTRODUCTORY LECTURELECTURE onon ROTATIONALROTATIONAL SPECTROSCOPYSPECTROSCOPY CristinaCristina PuzzariniPuzzarini Dip.Dip. ChimicaChimica ““GiacomoGiacomo CiamicianCiamician”” UniversitUniversitàà didi BolognaBologna CODECSCODECS SummerSummer SchoolSchool 20132013 THEORETICALTHEORETICAL SPECTROSCOPYSPECTROSCOPY EE Eel Evib Erot ELECTRONICELECTRONIC VIBRATIONALVIBRATIONAL ROTATIONALROTATIONAL FREQUENCYFREQUENCY REGIONREGION mm/submm waves Rotational Spectroscopy Electronics Photonics “Building”“Building” thethe ROTATIONALROTATIONAL SPECTRUMSPECTRUM intensity (a.u.) 0 20 40 60 80 100 frequency (cm-1) (1)(1) RotationalRotational energyenergy levelslevels (2)(2) SelectionSelection rules:rules: transitionstransitions allowedallowed (3)(3) IntensityIntensity (transitions)(transitions) CoordinateCoordinate SSyystemstemss Molecule-fixed coordinate system Lab-fixed coordinate system ROTATINGROTATING RIGIDRIGID BODYBODY (CLASSIC(CLASSIC VIEW)VIEW) 1 T ωTIω 2 == angolarangolar velocityvelocity II == inertiainertia tensortensor AngolarAngolar VelocitVelocityy vi r i x ω y RIGIDRIGID BODY:BODY: v ωr i i z InertiaInertia TensorTensor I xx I xy I xz n n 2 2 2 2 I xx mi ri xi mi yi zi i1 i1 I I yx I yy I yz n I xy mi xi yi i1 I zx I zy I zz ByBy cconvenonventiontion:: IIc IIb IIa INERTIAINERTIA TENSORTENSOR II Principal Principal I xx I xy I xz I x 0 0 inertiainertia I I yx I yy I yz systemsystem I 0 I y 0 I zx I zy I zz 0 0 I z AngularAngular MomentMoment RIGID BODY J e defined in the rotating -

Infrared Spectroscopy—Mid-Infrared, Near-Infrared, and Far-Infrared/Terahertz Spectroscopy

Analytical Sciences Advance Publication by J-STAGE Received December 17, 2020; Accepted February 11, 2021; Published online on February 19, 2021 DOI: 10.2116/analsci.20R008 Tutorial review Infrared Spectroscopy—Mid-infrared, Near-infrared, and Far-infrared/Terahertz Spectroscopy Yukihiro OZAKI1,2* 1School of Science and Technology, Kwansei Gakuin University, Sanda, Hyogo 669-1337, Japan 2Toyota Physical and Chemical Research Institute, Nagakute, Aichi 480-1192, Japan *corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract This article aims to overview infrared (IR) spectroscopy. Simultaneously, it outlines mid- infrared (MIR), near-infrared (NIR), and far-infrared (FIR) or terahertz (THz) spectroscopy separately, and compares them in terms of principles, characteristics, advantages, and applications. MIR spectroscopy is the central spectroscopic technique in the IR region, and is mainly concerned with the fundamentals of molecular vibrations. NIR spectroscopy incorporates both electronic and vibrational spectroscopy; however, in this review, I have chiefly discussed vibrational NIR spectroscopy, where bands due to overtones and combination modes appear. FIR or THz spectroscopy contains both vibrational and rotational spectroscopy. However, only vibrational FIR or THz spectroscopy has been discussed in this review. These three spectroscopy cover wide areas in their applications, making it rather difficult to describe these various topics simultaneously. Hence, I have selected three key topics: hydrogen bond studies, applications of quantum -

6 Basics of Optical Spectroscopy

Chapter 6, page 1 6 Basics of Optical Spectroscopy It is possible, with optical methods, to examine the rotational spectra of small molecules, all the Raman rotational spectra, the vibration spectra including the Raman spectra, and the electron spectra of the bonding electrons. Some of the quantum mechanical foundations of optical spectroscopy were already covered in chapter 3, and the optical methods will be the topic of chapter 7. This chapter is concerned with the relation between the structure of a substance to its rotational, and vibration spectra, and electron spectra of the bonding electrons. A few exceptions are made at the beginning of the chapter. Since the rotational spectrum of large molecules are examined using frequency variable microwave technology, this technology will be briefly explained. 6.1 Rotational Spectroscopy 6.1.1 Microwave Measurement Method Absorption measurements of the rotational transitions necessitates the existence of a permanent dipole moment. Molecules that have no permanent dipole moment, but rather an anisotropic polarizability perpendicular to the axis of rotation, can be measured with Raman scattering. Although rotational spectra of small molecules, e.g. HI, can be examined by optical methods in the distant infrared, the frequency of the rotational transitions is shifted to the range of HF spectroscopy in molecules with large moments of inertia. For this reason, rotational spectroscopy is often called microwave spectroscopy. For the production of microwaves, we could use electron time-of-flight tubes. The reflex klystron is only tunable over a small frequency range. The carcinotron (reverse wave tubes) is tunable over a larger range by variation of the accelerating voltage of the electron beam. -

Rotational Spectroscopy and Observational Astronomy of Prebiotic Molecules

Rotational Spectroscopy and Observational Astronomy of Prebiotic Molecules Thesis by Susanna Leigh Widicus Weaver In Partial Ful¯llment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California 2005 (Defended May 2, 2005) ii °c 2005 Susanna Leigh Widicus Weaver All Rights Reserved iii Acknowledgements I owe my gratitude to so many people for their guidance, assistance, friendship, and moral support during the completion of my graduate work. My time at Caltech has been an incredible experience, and I will always remember the wonderful people that I have met in the last few years. Thank you to Geo® Blake, my advisor, for showing all of us with his daily example that a person can indeed still have fun while being a scientist. Yet for all of the fun, you have also taught me how to look at all sides of an issue and how to ¯nd answers for myself, even when there might not be an answer to ¯nd. As a ¯rst-year student in your class I would have never guessed just how well I would know those numbers that I am supposed to keep in the back of my head! Also, thank you for teaching me when to be cautious and when to cut my losses, and especially how to make this choice e®ectively at 3 A.M. at an altitude of 14,000 feet. Thank you for opening the doors to the ¯eld of astrochemistry{I knew when I came to Caltech that I wanted to combine the ¯elds of chemistry and astronomy, and with your help I have now carved out my own niche in this exciting, emerging ¯eld. -

Rotational Spectroscopy

Rotational Spectroscopy Molecular rotations require little energy to excite them. Pure rotation spectra occur in the microwave region of the spectrum (~1 - 200 cm-1). It is important to note that a molecule cannot rotate about some arbitrary axis - the principle of conservation of angular momentum dictates that only a few rotations are possible. In general, rotation must be about the centre of mass of a molecule, and the axis must allow for conservation of angular momentum. In simple cases, this can often be recognised intuitively through symmetry - such as with the water molecule. A pure rotation spectrum can only arise when the molecule possesses a permanent electric dipole moment. Like with vibrational spectroscopy, the physical effect that couples to photons is a changing dipole moment. Since molecular bond lengths remain constant in pure rotation, the magnitude of a molecule's dipole cannot change. However, since electric dipole is a vector quantity (it has both size and direction) rotation can cause a permanent dipole to change direction, and hence we observe its spectra. Since homonuclear molecules such as dinitrogen (N2) have no dipole moment they have no rotation spectrum. Highly symmetric polyatomic molecules, such as carbon dioxide, also have no net dipole moment - the dipoles along the C-O bonds are always equal and opposite and cancel each other out. It is important to recognise also that if a molecule has a permanent dipole, but this dipole lies along the main rotation axis, then the molecule will not have a rotational spectrum - such as for a water molecule. In pure rotational spectroscopy for a simple diatomic molecule, the energy levels - as displayed below - are given by EJ = BJ(J+1), where J is the rotational quantum number, B is the rotational constant for the particular molecule given by B = h2 / 8π2I with the unit of Joules, where I is the moment of inertia, given by I = μr2 - where r is the bond length of this particular diatomic molecule and μ is the reduced mass, given by μ = m1m2 / m1 + m2.