Winter Music a Composer’S Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Masters at the Brooklyn Academy of Music

- NEW MASTERSAT THE BROOKLYNACADEMY OF MUSIC News Contact: Ellen Lampert/212.636.4123 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 13, 1982 Contacts: Ellen Lampert Susan Spier (212) 636-4123 Glenn Branca will present the world premiere of his SYMPHONY NO. 3 (Gloria) at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, January 13-16 as part of BAM's NEXT WAVE series. Performances in the Helen Owen Carey Playhouse will be Thursday through Saturday evenings (January 13-15) at 8:00pm and Sunday (January 16) at 2:00pm. SYMPHONY NO. 3 (Gloria) will continue Branca's use of home-made instruments, as exhibited in the electric stringed instruments he used in SYMPHONY No. 2 at St. Mark's Church last year. For SYMPHONY NO. 3, Branca has designed keyboard instruments which have been built by David Quinlan, a professional builder of harpsichords and folk instruments. The sixteen musicians for SYMPHONY No. 3 include Branca himself plus Jeffrey Glenn, Lee Ranaldo, Thurston Moore, Barbara Ess, David Quinlan, Craig Bromberg, and Stephen Wischerth on drums. Branca, tagged an "art-rocker" for his new music/rock experimentation, formed an experimental rock quintet with Jeffrey Lohn in 1977, called the Theoretical Girls. His next group was called The Static, a guitar-based trio, with which he moved from rock clubs to performances in alternative art spaces such as The Performing Garage. Known for the theatricality of his performances, Branca has toured throughout the U.S. and Eu rope with The Glenn Branca Group, a,,,J li.::!LO,dcd l'NO d;i.:.urns ·for 9;-j f<.eccrds, 'Lesson No. -

Meet Me by the Pleroma

MEET ME BY THE PLEROMA Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Electronic Music and Recording Media Mills College, May, 2009 By Charles Johnson Approved by: _______________________ Chris Brown Director of Thesis ________________________ Fred Frith Head, Music Department _________________________ Sandra C. Greer Provost and Dean of the Faculty Reading Committee: _______________________ James Fei _______________________ Pauline Oliveros Contents: 1. Introduction………………………………………………………….…..6 2. Development Process……………………………………………………9 2.1 Preliminary Work……..…………………….……………………….9 2.2 Materials…………..…………………….…………………….……15 2.3 The Form..…………………….……………………...……………..20 3. Context Within My Work………….……………………...……………21 4. Context Within My Interests…………………………………………....23 4.1 Musical Interests………………………..…………………………..23 4.2 The Sonic Other……….………………………..…………………..25 4.3 Philosophical, Social, Political…………………..………………….27 4.4 About the Title……….………………………..…………………….32 5. Concept…….………………………..…………………….…………….36 5.1 Why Difference Tones?………………….………………….………36 5.2 Considerations for the Performers……….………………….………37 5.3 Considerations for the Audience……….………………….………..38 6. Signal Flow Performance……….………………………….……………41 6.1 Staging……………………..…………………….…………………..41 6.2 Comments on Performance.…………………….…………………...42 6.3 Audience Reaction.………..…………………….…………………..43 7. Appendix A. Score to Meet me by the pleroma …………………………47 8. Appendix B. Technical details…………………………………………...50 9. Bibliography……………………………………………………………..54 -

Program Notes

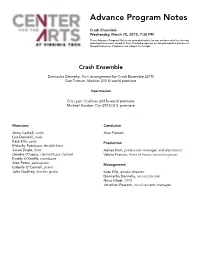

Advance Program Notes Crash Ensemble Wednesday, March 25, 2015, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Crash Ensemble Donnacha Dennehy: Turn (arrangement for Crash Ensemble 2015) Dan Truman: Marbles (2015) world premiere Intermission Eric Lyon: Dualities (2015) world premiere Michael Gordon: Dry (2013) U.S. premiere Musicians Conductor Anna Cashell, violin Alan Pierson Lisa Dowdall, viola Kate Ellis, cello Production Malachy Robinson, double bass Susan Doyle, flute Adrian Hart, production manager and electronics Deirdre O’Leary, clarinet/bass clarinet Valerie Francis , front of house sound engineer Roddy O’Keeffe, trombone Alex Petcu, percussion Management Isabelle O’Connell, piano John Godfrey, electric guitar Kate Ellis, artistic director Donnacha Dennehy, artistic partner Neva Elliott, CEO Jonathan Pearson, tour/concerts manager Program Notes TURN (2013-14; arrangement for Crash Ensemble, 2015; U.S. premiere) DONNACHA DENNEHY This intricate, detailed piece is one of the most overtly melodic of my purely instrumental works in years. Gently lunging melodies combine to produce a bustling tapestry of sound. Turn literally turns over its phrases, varying upon each repetition. Once I decided to dedicate this piece to my mother, an inveterate knitter, it struck me: that’s exactly what a turn is in knitting, a reworking on top of an already established stitched pattern! On a larger level Turn pushes towards build-ups that end each time with a literal turn in direction. This in a major way constitutes the modus operandi of the piece. -

The Kitchen Welcome's Back Avant-Garde Composer And

For Immediate Release January 20, 2015 THE KITCHEN WELCOME’S BACK AVANT-GARDE COMPOSER AND GUITARIST GLENN BRANCA TO PRESENT THE PREMIERE OF THE THIRD ASCENSION, FEBRUARY 23-24 Latest Development of Branca’s Influential 1981 Work The Ascension, Featuring Reg Bloor, Arad Evans and Owen Weaver The Kitchen welcomes back American avant-garde composer and guitarist Glenn Branca after more than twenty years for the premiere of The Third Ascension, a new work for guitar, bass, and drums. Conducted by Branca, this piece is the latest development of Branca’s influential 1981 work The Ascension, in which he experiments with resonances generated by alternate tunings for multiple electric guitars. Joining Branca will be Reg Bloor, Brendon Randall-Myers, Luke Schwartz and Arad Evans on guitar, Greg McMullen on bass, and Owen Weaver on drums. These shows will be recorded live for a subsequent album release. Artist Richard Prince has created a special poster for the concert, along with a limited-edition print. As a founder of the bands Theoretical Girls and Static in the seventies, Branca’s signature blend of hard rock with a contemporary music sensibility has earned him the title of "godfather of alternative rock." The importance of his music, particularly of The Ascension, is felt through the lasting impact it has made on its followers. In a 10.0-rated review of the album’s 2003 reissue, Pitchfork writes, “from these bloodied guitar strings and twisted metal carnage you can discern not just the euphoric guitar bliss of everyone from Sonic Youth to My Bloody Valentine, but also the mighty crescendos of Sigur Rós, Mogwai, Black Dice, Godspeed You Black Emperor!, or whomever, here executed with a plasma-like energy and melodic/harmonic structure still light-years beyond the forenamed.” The album has been called "one of the greatest rock albums ever made" (All Music) and “simply essential 20th-century music" (Tiny Mix Tapes). -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright The Electric Guitar in Contemporary Art Music Zane Mackie Banks A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Sydney Conservatorium of Music Sydney University 2013 Statement of Originality I declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. Signed: …………………………………………………………………………… Date: ………………………………………………………………………………. Abstract Since 1950 the electric guitar has occupied an ever-increasing presence in contemporary art music both as a solo and chamber instrument. -

May 23–June 11, 2016

FOR RELEASE: March 8, 2016 PROGRAM UPDATES AND Contact: Katherine E. Johnson NEW EVENTS ADDED (212) 875-5718; [email protected] UPDATED May 25, 2016 May 23–June 11, 2016 THREE-WEEK EXPLORATION OF TODAY’S MUSIC PRESENTED BY THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC AND TWELVE PARTNERS IN EIGHT VENUES THROUGHOUT NEW YORK CITY NEWLY ADDED: Insights Series: Free NY PHIL BIENNIAL Preview Night with Alan Gilbert, May 11 at David Rubenstein Atrium NY PHIL BIENNIAL Play Dates: Post-Concert Meet-Ups with Composers and Artists #biennialist Social Media Contest Programs for New York City Electroacoustic Music Festival with Works by More Than 30 Composers June 5–7, 2016, at National Sawdust BOULEZ’s Messagesquisse and STUCKY’s Second Concerto for Orchestra Added to Finale Program with Alan Gilbert and the New York Philharmonic In Tribute to the Late Composers June 11 at David Geffen Hall From May 23 to June 11, 2016, the New York Philharmonic and Music Director Alan Gilbert will present the second NY PHIL BIENNIAL, a wide-ranging exploration of today’s music by an array of contemporary and modern composers. A flagship project of the New York Philharmonic, the NY PHIL BIENNIAL brings together an international roster of composers, performers, and curatorial voices for concerts presented both on the Lincoln Center campus and in venues throughout the city. The 2016 NY PHIL BIENNIAL will feature works by more than 100 composers, more than half of whom are American, spanning in age and experience from students to iconic legends. Reflecting the Philharmonic’s growing collaborations with music education organizations from New York City to Asia, in the second NY PHIL BIENNIAL the Philharmonic will present new-music programs from some of the country’s top music schools, ranging from high school to university levels, and youth choruses from the East and West Coasts. -

Gbranca-Introduction-Interview.Pdf

Introduction Avant. The Journal of the Philosop hical-Interdisciplinary Vanguard Volume II, Number 2/2011 www.avant.edu.pl ISSN: 2082 -6710 Symphony No Introduction Witold Wachowski translation: Ewa Bodal An avant -garde composer, associated with progressive genres of music and controve r- sially rec eived works might seem to be an ideal – and thus, in a way, obvious – inter- locutor for the editors of a journal that itself decided to provoke with the word “avant” in its title. Nothing could be more wrong. It would be a misunderstanding to expect any fac ilitation , a miraculous coming together of thoughts on the science -art field, knowing winks of the eye, or understanding without unnecessary words. Glenn Branca is unruly and individualistic as an artist, but also unruly and individualistic as an interlocu tor. The exchange of opinions turned out to be far from easy, a few times we even “got one in the head”. Our provocative questions resulted in various, but a l- ways clear reactions from the American composer. Yet, even those questions which turned out to mis s the mark provided a rather brilliant picture of the creator’s attitude. Musical embodiment is, on many levels, consistently obvious for him. However, in Bra n- ca’s case this corresponds with an uncompromising approach of a progressive artist. He is also an artist who does not express a particular urge for cooperating with scientists, entering sub -personal areas of creating art and reception thereof. He does not need that; he works with a completely autonomous laboratory, and his body of work is co n- temporary in and of itself, and not through extra -artistic connections. -

Dueling with Symphonies by KYLE GANN TUESDAY, JUNE 26, 2001 at 4 A.M

Dueling With Symphonies BY KYLE GANN TUESDAY, JUNE 26, 2001 AT 4 A.M. 1 Glenn Branca’s latest piece starts out deafening and gets louder. In the late 1970s, Glenn Branca and Jeffrey Lohn invited Rhys Chatham to play bass with their band, Theoretical Girls, for a couple of gigs. Chatham was then music director of the Kitchen, and the aim was apparently to get the band a Kitchen gig, which it did. Chatham had been writing works for multiple guitars, such as his famous of 1977. By the early 1980s, Chatham and Branca both emerged writing for multiple guitar ensembles with unconventional tunings. But Branca, a rocker, put out records faster than the classically trained Chatham, and the critics gave him credit for all the innovations, referring to Chatham incorrectly as a member of Branca's band. Nasty words flew, and the two haven't spoken in many years. Around 1981 Branca started writing symphonies for six to 12 guitars. Chatham moved to Paris in 1987, where he wrote a piece for 100 electric guitars, , which premiered in Lille in 1989. He followed this with two more symphonies for 100 guitars, and none of the three have yet been played in New York. Branca planned out a giant symphony for 2000 guitars, intended to be performed in Paris—where Chatham lives—in 2000. The plans fell through, for reasons easy to imagine; as consolation, he performed his Symphony No. 13, titled , in New York, Chatham's hometown, on June 13, with—naturally—100 electric guitars. Chatham is scheduled to have performed in New York in guitars. -

Instrumental Modifications and Extended Performance Techniques

Instrumental modifications and extended performance techniques. The instrumentarium of Western music throughout its history has been in a state of continuous change, and every type and period of music has given rise to its own modifications of existing instruments and playing techniques. The desire for instruments capable of greater range, volume and dynamic control has led not only to the use of new materials and improvements in design but also to the invention of new instruments, many of which have achieved small success and are now regarded as little more than curiosities. These developments, naturally, form the matter of other articles in this dictionary, in which the evolution of individual instruments to their present state is fully described. The 20th century saw an unprecedented expansion in the instrumentarium and a host of new approaches by composers and performers to the use of existing instruments; because these experiments often took place outside the mainstream of musical life it seems appropriate to discuss them as a group. 1. Introduction. In the second half of the 20th century the problem of creating a repertory for a new or modified instrument became less significant than in the past, when even instruments for which major composers wrote important works (such as Schubert's Sonata for arpeggione and piano, d821) were not thereby guaranteed survival; indeterminate and graphic scores and compositions with unspecified instrumentation, together with various areas of free improvisation, have supplemented the compositions of those who often combine the three distinct functions of instrument inventor and/or builder, performer and composer in a single person. -

This Interview with Glenn Branca Was Conducted with Brian Bridges by Telephone on Friday 18Th April, 2003, and Lasted Approximately 1Hr, 10 Mins

This interview with Glenn Branca was conducted with Brian Bridges by telephone on Friday 18th April, 2003, and lasted approximately 1hr, 10 mins. The following is an edited transcript. GB: So you wanted to know how I got into the tuning stuff? BB: Yeah, and what was the whole progression...One thing I was listening to today was Symphony No. 1 and I noticed...did I hear a just tuned fifth: were you beginning to throw in all sorts of tuning systems and then have them ‘slug it out’...and then the whole harmonic series thing developed, or what was the real genesis? GB: Well in the late seventies, I started doing a rock band, and then I wanted to do things with rock instruments that were a little more interesting to me than doing a rock band - it was an experimental band called Theoretical Girls and, ah, so I still had a lot of ideas about experimenting with guitars that weren’t gonna work with the band, so I started working with, like, a number of guitars. I wrote my first piece called Instrumental for Six Guitars and, ah, at that point is when I started fooling around with tuning - well, that was just another one of the experiments that I was doing, and it worked out really well, this kind of octave tuning that I came up with, where all the strings were tuned to the same note, but in three octaves, and I found that there was a lot I could do especially [indistinct] clusters. And the sound of that particular piece was so interesting to me that I figured I needed to start developing that, and eventually I dropped the whole idea of the band and started just working on this whole guitar-type thing. -

Academy of Music

1 P153s. oo3cf;- BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC BOARD OF TRUSTEES Hon. Edward I. Koch, Hon. Howard Golden, Seth Faison, Paul Lepercq, Honorary Chairmen; Neil D. Chrisman, Chairman; Rita Hillman, I. Stanley Kriegel. Ame Vennema. Franklin R. Weissberg, Vice Chairmen; Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Chief Executive Officer; Henry Bing, Jr.. Warren B. Coburn, Charles M. Diker, Jeffrey K. Endervelt, Mallory Factor, Harold L. Fisher, Leonard Garment, Elisabeth Gotbaum, Sidney Kantor, Eugene H. Luntey, Hamish Maxwell, Evelyn Ortner, John R. Price, Jr., Richard M. Rosan, Mrs. Marion Scotto, William Tobey, Curtis A. Wood, John E. Zuccotti. OFFICERS Harvey Lichtenstein President and Chief Executive Officer Judith E. Daykin Executive Vice President and Genera! Manager Richard Balzano Vice President and Treasurer Karen Brooks Hopkins Vice President for Planning and Development ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE STAFF Ruth Goldblatt Assistant to President Sally Morgan Assistant to General Manager David Perry Mail Clerk FINANCE Perry Singer Accountant Jack C. Nulsen Business Manager Pearl Light Payroll Manager MARKETING AND PROMOTION it Marketing Nancy Rossell Marketing Coordinator BARI Susan Levy Director, of Audience Development Jerrilyn Brown Executive Assistant Jon Crow Graphics Margo Abbruscato Information Resource Coordinator Press Ellen Lampert General Press Representative Susan Hood Spier Associate Press Representative Diana Robinson Press Assistant Tom Caravaglia House Photographer PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT Jacques Brunswick Director of Membership Denis Azaro -

Product of Culture-Clash: the Theatre of Eternal Music And

Product of Culture-Clash: social scene, patronage and group dynamics in the early New York Downtown scene and the Theatre of Eternal Music1 Brian Bridges Introduction This article will explore the background to the establishment of the Downtown avant- garde art and music scene in New York, including a survey of the role of the experimental composer in American music. It will investigate cultural interactions and influences between some of the main players in the early Downtown scene, focusing in particular on the Theatre of Eternal Music (TEM), the ensemble formed in the 1960s by New York-based “founding-father” Minimalist La Monte Young. It will examine some of the cross-pollination which occurred between the group and the environment in which it developed and will briefly survey the manner in which historical accounts have attributed varying degrees of credit to members of the group, along with a brief account of the current dispute between Young on the one hand and Tony Conrad and John Cale on the other. 1. Scene-setting The art world in 1960s New York enjoyed the healthy combination of low rents in Downtown spaces (which could be retrofitted for both accommodation and display purposes) and a fortuitous proximity to rich patrons. In keeping with the restless Social Darwinistic nature of the city, these patrons were often interested in funding artistic endeavours which evoked and reflected a certain “edginess”. Along with the changing roles of curators, dealers and galleries in promoting the works of living artists to an unprecedented degree, this created a distinctly favourable situation for many visual artists.