Dueling with Symphonies by KYLE GANN TUESDAY, JUNE 26, 2001 at 4 A.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Masters at the Brooklyn Academy of Music

- NEW MASTERSAT THE BROOKLYNACADEMY OF MUSIC News Contact: Ellen Lampert/212.636.4123 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 13, 1982 Contacts: Ellen Lampert Susan Spier (212) 636-4123 Glenn Branca will present the world premiere of his SYMPHONY NO. 3 (Gloria) at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, January 13-16 as part of BAM's NEXT WAVE series. Performances in the Helen Owen Carey Playhouse will be Thursday through Saturday evenings (January 13-15) at 8:00pm and Sunday (January 16) at 2:00pm. SYMPHONY NO. 3 (Gloria) will continue Branca's use of home-made instruments, as exhibited in the electric stringed instruments he used in SYMPHONY No. 2 at St. Mark's Church last year. For SYMPHONY NO. 3, Branca has designed keyboard instruments which have been built by David Quinlan, a professional builder of harpsichords and folk instruments. The sixteen musicians for SYMPHONY No. 3 include Branca himself plus Jeffrey Glenn, Lee Ranaldo, Thurston Moore, Barbara Ess, David Quinlan, Craig Bromberg, and Stephen Wischerth on drums. Branca, tagged an "art-rocker" for his new music/rock experimentation, formed an experimental rock quintet with Jeffrey Lohn in 1977, called the Theoretical Girls. His next group was called The Static, a guitar-based trio, with which he moved from rock clubs to performances in alternative art spaces such as The Performing Garage. Known for the theatricality of his performances, Branca has toured throughout the U.S. and Eu rope with The Glenn Branca Group, a,,,J li.::!LO,dcd l'NO d;i.:.urns ·for 9;-j f<.eccrds, 'Lesson No. -

Meet Me by the Pleroma

MEET ME BY THE PLEROMA Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Electronic Music and Recording Media Mills College, May, 2009 By Charles Johnson Approved by: _______________________ Chris Brown Director of Thesis ________________________ Fred Frith Head, Music Department _________________________ Sandra C. Greer Provost and Dean of the Faculty Reading Committee: _______________________ James Fei _______________________ Pauline Oliveros Contents: 1. Introduction………………………………………………………….…..6 2. Development Process……………………………………………………9 2.1 Preliminary Work……..…………………….……………………….9 2.2 Materials…………..…………………….…………………….……15 2.3 The Form..…………………….……………………...……………..20 3. Context Within My Work………….……………………...……………21 4. Context Within My Interests…………………………………………....23 4.1 Musical Interests………………………..…………………………..23 4.2 The Sonic Other……….………………………..…………………..25 4.3 Philosophical, Social, Political…………………..………………….27 4.4 About the Title……….………………………..…………………….32 5. Concept…….………………………..…………………….…………….36 5.1 Why Difference Tones?………………….………………….………36 5.2 Considerations for the Performers……….………………….………37 5.3 Considerations for the Audience……….………………….………..38 6. Signal Flow Performance……….………………………….……………41 6.1 Staging……………………..…………………….…………………..41 6.2 Comments on Performance.…………………….…………………...42 6.3 Audience Reaction.………..…………………….…………………..43 7. Appendix A. Score to Meet me by the pleroma …………………………47 8. Appendix B. Technical details…………………………………………...50 9. Bibliography……………………………………………………………..54 -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

Program Notes

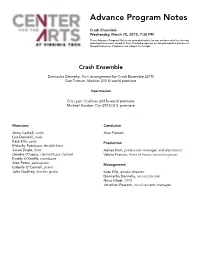

Advance Program Notes Crash Ensemble Wednesday, March 25, 2015, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Crash Ensemble Donnacha Dennehy: Turn (arrangement for Crash Ensemble 2015) Dan Truman: Marbles (2015) world premiere Intermission Eric Lyon: Dualities (2015) world premiere Michael Gordon: Dry (2013) U.S. premiere Musicians Conductor Anna Cashell, violin Alan Pierson Lisa Dowdall, viola Kate Ellis, cello Production Malachy Robinson, double bass Susan Doyle, flute Adrian Hart, production manager and electronics Deirdre O’Leary, clarinet/bass clarinet Valerie Francis , front of house sound engineer Roddy O’Keeffe, trombone Alex Petcu, percussion Management Isabelle O’Connell, piano John Godfrey, electric guitar Kate Ellis, artistic director Donnacha Dennehy, artistic partner Neva Elliott, CEO Jonathan Pearson, tour/concerts manager Program Notes TURN (2013-14; arrangement for Crash Ensemble, 2015; U.S. premiere) DONNACHA DENNEHY This intricate, detailed piece is one of the most overtly melodic of my purely instrumental works in years. Gently lunging melodies combine to produce a bustling tapestry of sound. Turn literally turns over its phrases, varying upon each repetition. Once I decided to dedicate this piece to my mother, an inveterate knitter, it struck me: that’s exactly what a turn is in knitting, a reworking on top of an already established stitched pattern! On a larger level Turn pushes towards build-ups that end each time with a literal turn in direction. This in a major way constitutes the modus operandi of the piece. -

Someone in the Kitchen with Music

'omeone's in The Kitchen, with Music NE night a soprano simply a space where com- cause concert halls generally were ready to do public con- his best to describe the crawls out from under posers can organize their have proscenium' stages . But certs yet. And in concerts pieces. "There will be a pure a piano to sing a con- own concerts. As such, it is the opportunity to manipu- which involve traditional in- electronic piece by Laurie temporary song. An- not a very good outlet for late the performance space struments ; we have to see Spiegel, and a `tape piece by other night a cellist is lying composers seeking perform- has proved to be an impor- to it that all the performers Jim Burton which incorpo- on a bed of television sets ances of string quartets or tant stimulus to composers. will be of professional cal- rates some dialogue. Then playing her instrument while song cycles. But it is ideal it has been particularly use- iber . And, of course, there' there will be two short thea- the audience mills around. for composers of electronic ful for electronic composers, is not much point in our do- ter pieces by Mike Levenson. Another night a chorus of 20 music, composers who per- who found out long ago that, ing performances of Webern, One he performs in a gorilla people is wandering around form their own music, and without a live performer to Varese, or even Stockhausen, mask, and the other is a the room making strange composers who, for various focus on, it was difficult to because those things are pro- snare drum solo with socio- gurgling sounds with their reasons, want to control the draw audiences into their gramed frequently by groups political overtones. -

Album Reviews

Album Reviews I’ve written over 150 album reviews as a volunteer for CHIRPRadio.org. Here are some examples, in alphabetical order: Caetano Veloso Caetano Veloso (A Little More Blue) Polygram / 1971 Brazilian Caetano Veloso’s third self-titled album was recorded in England while in exile after being branded ‘subversive’ by the Brazilian government. Under colorful plumes of psychedelic folk, these songs are cryptic stories of an outsider and traveller, recalling both the wonder of new lands and the oppressiveness of the old. The whole album is recommended, but gems include the autobiographical “A Little More Blue” with it’s Brazilian jazz acoustic guitar, the airy flute and warm chorus of “London, London” and the somber Baroque folk of “In the Hot Sun of a Christmas Day” tells the story of tragedy told with jazzy baroque undertones of “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen.” The Clash London Calling Epic / 1979 London Calling, considered one of the greatest rock & roll albums ever recorded, is far from a straightforward: punk, reggae, ska, R&B and rockabilly all have tickets to this show of force that’s both pop and revolutionary. The title track opens with a blistering rallying cry of ska guitar and apocalypse. The post-disco “Clampdown” is a template for the next decade, a perfect mix of gloss and message. “The Guns of Brixton” is reggae-punk in that order, with rocksteady riffs and rock drums creating an intense portrait of defiance. “Train in Vain” is a harmonica puffing, Top 40 gem that stands at the crossroads of punk and rock n’ roll. -

The Kitchen Welcome's Back Avant-Garde Composer And

For Immediate Release January 20, 2015 THE KITCHEN WELCOME’S BACK AVANT-GARDE COMPOSER AND GUITARIST GLENN BRANCA TO PRESENT THE PREMIERE OF THE THIRD ASCENSION, FEBRUARY 23-24 Latest Development of Branca’s Influential 1981 Work The Ascension, Featuring Reg Bloor, Arad Evans and Owen Weaver The Kitchen welcomes back American avant-garde composer and guitarist Glenn Branca after more than twenty years for the premiere of The Third Ascension, a new work for guitar, bass, and drums. Conducted by Branca, this piece is the latest development of Branca’s influential 1981 work The Ascension, in which he experiments with resonances generated by alternate tunings for multiple electric guitars. Joining Branca will be Reg Bloor, Brendon Randall-Myers, Luke Schwartz and Arad Evans on guitar, Greg McMullen on bass, and Owen Weaver on drums. These shows will be recorded live for a subsequent album release. Artist Richard Prince has created a special poster for the concert, along with a limited-edition print. As a founder of the bands Theoretical Girls and Static in the seventies, Branca’s signature blend of hard rock with a contemporary music sensibility has earned him the title of "godfather of alternative rock." The importance of his music, particularly of The Ascension, is felt through the lasting impact it has made on its followers. In a 10.0-rated review of the album’s 2003 reissue, Pitchfork writes, “from these bloodied guitar strings and twisted metal carnage you can discern not just the euphoric guitar bliss of everyone from Sonic Youth to My Bloody Valentine, but also the mighty crescendos of Sigur Rós, Mogwai, Black Dice, Godspeed You Black Emperor!, or whomever, here executed with a plasma-like energy and melodic/harmonic structure still light-years beyond the forenamed.” The album has been called "one of the greatest rock albums ever made" (All Music) and “simply essential 20th-century music" (Tiny Mix Tapes). -

Rethinking Minimalism: at the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism

Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism Peter Shelley A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee Jonathan Bernard, Chair Áine Heneghan Judy Tsou Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music Theory ©Copyright 2013 Peter Shelley University of Washington Abstract Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism Peter James Shelley Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Jonathan Bernard Music Theory By now most scholars are fairly sure of what minimalism is. Even if they may be reluctant to offer a precise theory, and even if they may distrust canon formation, members of the informed public have a clear idea of who the central canonical minimalist composers were or are. Sitting front and center are always four white male Americans: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass. This dissertation negotiates with this received wisdom, challenging the stylistic coherence among these composers implied by the term minimalism and scrutinizing the presumed neutrality of their music. This dissertation is based in the acceptance of the aesthetic similarities between minimalist sculpture and music. Michael Fried’s essay “Art and Objecthood,” which occupies a central role in the history of minimalist sculptural criticism, serves as the point of departure for three excursions into minimalist music. The first excursion deals with the question of time in minimalism, arguing that, contrary to received wisdom, minimalist music is not always well understood as static or, in Jonathan Kramer’s terminology, vertical. The second excursion addresses anthropomorphism in minimalist music, borrowing from Fried’s concept of (bodily) presence. -

Winter Music a Composer’S Journal

CD 82 How the subarctic winter light inspired new music of elemental harmony and colour From Winter Music A Composer’s Journal by John Luther Adams For the past twenty-five years composer John Luther Adams has made his home in the boreal forest near Fairbanks, Alaska. From there he has created a unique musical world, grounded in the elemental landscapes and indigenous cultures of the North. Each winter— which, he says, “is the season when I burrow most deeply into my music”—he keeps a daily journal as he tries to understand where the music is leading him. The winter of 1998–99 was a time of change, as he com- posed a major new piece entitled The Immeasurable Space of Tones. The present article comprises journal selections from that period and is excerpted from Winter Music: Selected Writings 1974–2000—a book in progress that includes journals, essays, and other writ- pho tos by Gayle Young ings by John Luther Adams. 32 MUSICWORKS 82 WINTER 2002 Winter Solstice, 1998 January 20, 1999 For much of the year, the world in which I live is a vast, For me, composing is not about finding the notes. It’s white canvas. In the deep stillness of the solstice, I’m pro- about losing them. Although I’m still involved in writing foundly moved by the exquisite colours of the subarctic scores, the most difficult thing is not to know what to write winter light on snow. Reading art critic John Gage’s essay down; it’s to know what not to write down. -

Download This

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE The Crossing Contact: Katy Salomon | Morahan Arts and Media [email protected] | 863.660.2214 Annenberg Center Contact: Katherine Blodgett | Communications Consulting [email protected] | 215.431.1230 The Crossing and the Annenberg Center Present The Month of Moderns 2021 Outdoors and Spatially Distanced in New Hope, West Philadelphia, and Germantown Using Echoes Amplification Kits June 3-6: The Forest at Bowman's Hill Wildflower Preserve in New Hope June 11-13: The World Premiere of Matana Roberts’ “we got time.”, a Work Honoring the Life of Breonna Taylor, with Ars Nova Workshop at The Woodlands in West Philadelphia June 18-19: The World Premieres of Wang Lu’s At which point and Ayanna Woods’ Shift and the US Premiere of David Lang’s the sense of senses at Awbury Arboretum in Germantown “[A] gift for lending social activism poetic form.” – The New York Times www.crossingchoir.org Philadelphia, PA (April 28, 2021) — Grammy® Award-winning choir The Crossing, led by Donald Nally, announces the return of its annual summer festival of new music, The Month of Moderns 2021, co-presented with the Annenberg Center from June 3-19, 2021. Each of the three outdoor programs, spread throughout Philadelphia and neighboring New Hope, will be performed with singers and audience spatially distanced using The Crossing’s Echoes Amplification Kits designed by in-house sound designer Paul Vazquez, which allow an intimate aural experience while observing pandemic-time protocols. The Crossing will reprise their sold-out October 2020 run of The Forest at Bowman's Hill Wildflower Preserve in New Hope from June 3-6, 2021; perform the world premiere of Matana Roberts’ “we got time.”, a work honoring the life of Breonna Taylor, presented in collaboration with Ars Nova Workshop at The Woodlands in West Philadelphia from June 11- 13, 2021; and present the world premieres of At which point by Wang Lu and an expanded version of Ayanna Woods’ Shift, plus the U.S. -

Ecstatic Music Festival™ 2012 Oneida & Rhys Chatham

Merkin Concert Hall Saturday, March 17, 2012 at 7:30 pm Kaufman Center presents Ecstatic Music Festival™ 2012 Oneida & Rhys Chatham The program will be announced from the stage. Oneida Hanoi Jane, guitar Showtime, guitar Snaps London, synths, organ and effects Bobby Matador, organ, bass guitar and vocals Kid Millions, drums and vocals Rhys Chatham, composer, guitar and trumpet About the Ecstatic Music Festival The Ecstatic Music Festival was inaugurated in 2011 by Kaufman Center (kaufman-center.org). Deeply committed to music education and performance that incorporate the ideas and trends of the 21st century, the Center sought to put truly modern music on its stage—redefining music for the post-classical generation, and serving it up to new audiences. Until now, the blurry lines between the classical and pop genres were typically crossed in downtown clubs and alternative spaces. The Ecstatic Music Festival has brought that new stuff into a more traditional concert hall setting, where a relaxed atmosphere meets up with the exquisite acoustics that the artists and the music deserve. Under the inspired direction of curator Judd Greenstein, the Ecstatic Music Festival’s programs give true meaning to the notion of “Ecstatic Music” as a joyful and adventurous collaboration between composers and performers from the indie/pop and classical realms. This year’s Ecstatic Music Festival includes three New Sounds® Live concerts hosted by WNYC’s John Schaefer, which are webcast live on Q2 Music and taped for future broadcast on WNYC. Q2 Music is the festival’s digital venue and the center for on-demand artist interviews and concert audio. -

100 Guitar Orchestra

RHYS CHATHAM SS A CRIMSON GRAIL ’ (100 GUITAR ORCHESTRA) USA | PRESENTED IN ASSOCIATION WITH ROOM40 John Johnson Photo: RHYS CHATHAM’S A CRIMSON GRAIL ABOUT RHYS CHATHAM (100 GUITAR ORCHESTRA) USA Rhys Chatham is a composer and multi- PRESENTED IN ASSOCIATION WITH ROOM40 instrumentalist from Manhattan, currently CARRIAGEWORKS living in Paris. He was the founder of the 12 & 13 JANUARY music program at The Kitchen in downtown Manhattan in 1971 and was its music director between 1971–73 and 1977–80. Rhys Chatham altered the DNA of rock and created a new type of urban music by fusing Composer & Dan Cunningham Frank Macias the overtone-drenched minimalism of John Conductor Simon Dawes Robert MacManus Cale and Tony Conrad with the relentless, Rhys Chatham Jacob Dawson-Daley Nick Maher elemental fury of the Ramones – the textural intricacies of the avant-garde colliding with Concertmaster Iain Downie Joe Manton the visceral punch of electric guitar-slinging David Daniell James Dunlop Luke Martin punk rock. Section Conductors David Eastwood Gerard Mason With Rhys Chatham’s composition Guitar Lisa MacKinney Max Edgar Asher McLoughlin (1977), he became the first composer to Bonnie Mercer Trio Gary Evesson Mark Morse make use of multiple electric guitars in special Julia Reidy Sam Filmer Louis Mullins tunings to merge the extended-time music David Daniell Justin Finch Ben Murphy of the sixties and seventies with serious hard Producer, Manager Tony Flint Stuart Neale rock. Chatham continued this pursuit over & Technical Director the next decade, culminating in 1989 with Scott Fraser Daniel Nesci Regina Greene, the composition and performance of his first Front Porch Productions John Gnanasekaran Carla Oliver symphony for an orchestra of one hundred Andrew Green Liam O'Shea electric guitars, An Angel Moves Too Fast to Audio Technician Harry Hadley Stephen O'Sullivan See.