John Zorn Provides Us with Many Valu- Able Insights Relating to the Composer’S Aesthetic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Masters at the Brooklyn Academy of Music

- NEW MASTERSAT THE BROOKLYNACADEMY OF MUSIC News Contact: Ellen Lampert/212.636.4123 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE December 13, 1982 Contacts: Ellen Lampert Susan Spier (212) 636-4123 Glenn Branca will present the world premiere of his SYMPHONY NO. 3 (Gloria) at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, January 13-16 as part of BAM's NEXT WAVE series. Performances in the Helen Owen Carey Playhouse will be Thursday through Saturday evenings (January 13-15) at 8:00pm and Sunday (January 16) at 2:00pm. SYMPHONY NO. 3 (Gloria) will continue Branca's use of home-made instruments, as exhibited in the electric stringed instruments he used in SYMPHONY No. 2 at St. Mark's Church last year. For SYMPHONY NO. 3, Branca has designed keyboard instruments which have been built by David Quinlan, a professional builder of harpsichords and folk instruments. The sixteen musicians for SYMPHONY No. 3 include Branca himself plus Jeffrey Glenn, Lee Ranaldo, Thurston Moore, Barbara Ess, David Quinlan, Craig Bromberg, and Stephen Wischerth on drums. Branca, tagged an "art-rocker" for his new music/rock experimentation, formed an experimental rock quintet with Jeffrey Lohn in 1977, called the Theoretical Girls. His next group was called The Static, a guitar-based trio, with which he moved from rock clubs to performances in alternative art spaces such as The Performing Garage. Known for the theatricality of his performances, Branca has toured throughout the U.S. and Eu rope with The Glenn Branca Group, a,,,J li.::!LO,dcd l'NO d;i.:.urns ·for 9;-j f<.eccrds, 'Lesson No. -

John Zorn Artax David Cross Gourds + More J Discorder

John zorn artax david cross gourds + more J DiSCORDER Arrax by Natalie Vermeer p. 13 David Cross by Chris Eng p. 14 Gourds by Val Cormier p.l 5 John Zorn by Nou Dadoun p. 16 Hip Hop Migration by Shawn Condon p. 19 Parallela Tuesdays by Steve DiPo p.20 Colin the Mole by Tobias V p.21 Music Sucks p& Over My Shoulder p.7 Riff Raff p.8 RadioFree Press p.9 Road Worn and Weary p.9 Bucking Fullshit p.10 Panarticon p.10 Under Review p^2 Real Live Action p24 Charts pJ27 On the Dial p.28 Kickaround p.29 Datebook p!30 Yeah, it's pink. Pink and blue.You got a problem with that? Andrea Nunes made it and she drew it all pretty, so if you have a problem with that then you just come on over and we'll show you some more of her artwork until you agree that it kicks ass, sucka. © "DiSCORDER" 2002 by the Student Radio Society of the Un versify of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circulation 17,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN ilsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money ordei payable to DiSCORDER Magazine, DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the December issue is Noven ber 13th. Ad space is available until November 27th and can be booked by calling Steve at 604.822 3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. -

Meet Me by the Pleroma

MEET ME BY THE PLEROMA Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Fine Arts in Electronic Music and Recording Media Mills College, May, 2009 By Charles Johnson Approved by: _______________________ Chris Brown Director of Thesis ________________________ Fred Frith Head, Music Department _________________________ Sandra C. Greer Provost and Dean of the Faculty Reading Committee: _______________________ James Fei _______________________ Pauline Oliveros Contents: 1. Introduction………………………………………………………….…..6 2. Development Process……………………………………………………9 2.1 Preliminary Work……..…………………….……………………….9 2.2 Materials…………..…………………….…………………….……15 2.3 The Form..…………………….……………………...……………..20 3. Context Within My Work………….……………………...……………21 4. Context Within My Interests…………………………………………....23 4.1 Musical Interests………………………..…………………………..23 4.2 The Sonic Other……….………………………..…………………..25 4.3 Philosophical, Social, Political…………………..………………….27 4.4 About the Title……….………………………..…………………….32 5. Concept…….………………………..…………………….…………….36 5.1 Why Difference Tones?………………….………………….………36 5.2 Considerations for the Performers……….………………….………37 5.3 Considerations for the Audience……….………………….………..38 6. Signal Flow Performance……….………………………….……………41 6.1 Staging……………………..…………………….…………………..41 6.2 Comments on Performance.…………………….…………………...42 6.3 Audience Reaction.………..…………………….…………………..43 7. Appendix A. Score to Meet me by the pleroma …………………………47 8. Appendix B. Technical details…………………………………………...50 9. Bibliography……………………………………………………………..54 -

Джоð½ Зоñ€Ð½ ÐлÐ

Джон Зорн ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Ð ´Ð¸ÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) The Big Gundown https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-big-gundown-849633/songs Spy vs Spy https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spy-vs-spy-249882/songs Buck Jam Tonic https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/buck-jam-tonic-2927453/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/six-litanies-for-heliogabalus- Six Litanies for Heliogabalus 3485596/songs Late Works https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/late-works-3218450/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/templars%3A-in-sacred-blood- Templars: In Sacred Blood 3493947/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/moonchild%3A-songs-without-words- Moonchild: Songs Without Words 3323574/songs The Crucible https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-crucible-966286/songs Ipsissimus https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ipsissimus-3154239/songs The Concealed https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-concealed-1825565/songs Spillane https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spillane-847460/songs Mount Analogue https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/mount-analogue-3326006/songs Locus Solus https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/locus-solus-3257777/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/at-the-gates-of-paradise- At the Gates of Paradise 2868730/songs Ganryu Island https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ganryu-island-3095196/songs The Mysteries https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-mysteries-15077054/songs A Vision in Blakelight -

Experimental

Experimental Discussão de alguns exemplos Earle Brown ● Earle Brown (December 26, 1926 – July 2, 2002) was an American composer who established his own formal and notational systems. Brown was the creator of open form,[1] a style of musical construction that has influenced many composers since—notably the downtown New York scene of the 1980s (see John Zorn) and generations of younger composers. ● ● Among his most famous works are December 1952, an entirely graphic score, and the open form pieces Available Forms I & II, Centering, and Cross Sections and Color Fields. He was awarded a Foundation for Contemporary Arts John Cage Award (1998). Terry Riley ● Terrence Mitchell "Terry" Riley (born June 24, 1935) is an American composer and performing musician associated with the minimalist school of Western classical music, of which he was a pioneer. His work is deeply influenced by both jazz and Indian classical music, and has utilized innovative tape music techniques and delay systems. He is best known for works such as his 1964 composition In C and 1969 album A Rainbow in Curved Air, both considered landmarks of minimalist music. La Monte Young ● La Monte Thornton Young (born October 14, 1935) is an American avant-garde composer, musician, and artist generally recognized as the first minimalist composer.[1][2][3] His works are cited as prominent examples of post-war experimental and contemporary music, and were tied to New York's downtown music and Fluxus art scenes.[4] Young is perhaps best known for his pioneering work in Western drone music (originally referred to as "dream music"), prominently explored in the 1960s with the experimental music collective the Theatre of Eternal Music. -

Some Notes on John Zorn's Cobra

Some Notes on John Zorn’s Cobra Author(s): JOHN BRACKETT Source: American Music, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Spring 2010), pp. 44-75 Published by: University of Illinois Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/americanmusic.28.1.0044 . Accessed: 10/12/2013 15:16 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Music. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 198.40.30.166 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 15:16:53 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions JOHN BRACKETT Some Notes on John Zorn’s Cobra The year 2009 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of John Zorn’s cele- brated game piece for improvisers, Cobra. Without a doubt, Cobra is Zorn’s most popular and well-known composition and one that has enjoyed remarkable success and innumerable performances all over the world since its premiere in late 1984 at the New York City club, Roulette. Some noteworthy performances of Cobra include those played by a group of jazz journalists and critics, an all-women performance, and a hip-hop ver- sion as well!1 At the same time, Cobra is routinely played by students in colleges and universities all over the world, ensuring that the work will continue to grow and evolve in the years to come. -

Program Notes

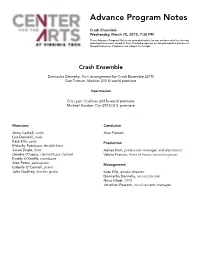

Advance Program Notes Crash Ensemble Wednesday, March 25, 2015, 7:30 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. Crash Ensemble Donnacha Dennehy: Turn (arrangement for Crash Ensemble 2015) Dan Truman: Marbles (2015) world premiere Intermission Eric Lyon: Dualities (2015) world premiere Michael Gordon: Dry (2013) U.S. premiere Musicians Conductor Anna Cashell, violin Alan Pierson Lisa Dowdall, viola Kate Ellis, cello Production Malachy Robinson, double bass Susan Doyle, flute Adrian Hart, production manager and electronics Deirdre O’Leary, clarinet/bass clarinet Valerie Francis , front of house sound engineer Roddy O’Keeffe, trombone Alex Petcu, percussion Management Isabelle O’Connell, piano John Godfrey, electric guitar Kate Ellis, artistic director Donnacha Dennehy, artistic partner Neva Elliott, CEO Jonathan Pearson, tour/concerts manager Program Notes TURN (2013-14; arrangement for Crash Ensemble, 2015; U.S. premiere) DONNACHA DENNEHY This intricate, detailed piece is one of the most overtly melodic of my purely instrumental works in years. Gently lunging melodies combine to produce a bustling tapestry of sound. Turn literally turns over its phrases, varying upon each repetition. Once I decided to dedicate this piece to my mother, an inveterate knitter, it struck me: that’s exactly what a turn is in knitting, a reworking on top of an already established stitched pattern! On a larger level Turn pushes towards build-ups that end each time with a literal turn in direction. This in a major way constitutes the modus operandi of the piece. -

The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-27-2013 Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, David Allen, "Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The hiP lip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1098. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1098 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Patrick Burke Pannill Camp Mary-Jean Cowell Craig Monson Paul Steinbeck Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966–1976 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. All rights reserved. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... -

John Zorn. the Gift; Songs from the Hermetic Theatre (2001). Chimeras; Masada Guitars (2003)

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2008-01-01 John Zorn. The Gift; Songs from the Hermetic Theatre (2001). Chimeras; Masada Guitars (2003). Masada Recital; Magick (2004). Rituals (2005). Astronome; Masada Rock; Moonchild Christian T. Asplund [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Music Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Asplund, Christian T., "John Zorn. The Gift; Songs from the Hermetic Theatre (2001). Chimeras; Masada Guitars (2003). Masada Recital; Magick (2004). Rituals (2005). Astronome; Masada Rock; Moonchild" (2008). Faculty Publications. 914. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/914 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. RecordingReviews 129 JohnZorn. TheGift; Songs from the Hermetic Theatre (2001). Chimeras;Mas- ada Guitars(2003). Masada Recital;Magick (2004). Rituals (2005). Astronome; MasadaRock; Moonchild (2006). Each of these recordings appears on John Zorn'sown label,Tzadik. Once the unrulyupstart, John Zorn is now a MacArthurfellow, whose formi- dable catalogdivides easily intoearly, middle, and late periods.The earlyperiod dates fromthe mid-1970s to themid-1980s, when Zorn pioneeredthe practice of "comprovisation,"a termused to describe"the making of new compositionsfrom recordingsof improvised material/'1 Ultimately, Zorn's comprovisationblurs the lines between active listenerand composer,since both createnew works when theyimpose structureon foundsonic material.His earlystructuralist-modernist approach to comprovisationproduced esoteric,often severely pointillist music, and evolved into thegame pieces of the late 1970s and early 1980s,culminating in themasterpiece of strategy,Cobra (1984), the last early-periodwork. -

Battles Around New Music in New York in the Seventies

Presenting the New: Battles around New Music in New York in the Seventies A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David Grayson, Adviser December 2012 © Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher 2012 i Acknowledgements One of the best things about reaching the end of this process is the opportunity to publicly thank the people who have helped to make it happen. More than any other individual, thanks must go to my wife, who has had to put up with more of my rambling than anybody, and has graciously given me half of every weekend for the last several years to keep working. Thank you, too, to my adviser, David Grayson, whose steady support in a shifting institutional environment has been invaluable. To the rest of my committee: Sumanth Gopinath, Kelley Harness, and Richard Leppert, for their advice and willingness to jump back in on this project after every life-inflicted gap. Thanks also to my mother and to my kids, for different reasons. Thanks to the staff at the New York Public Library (the one on 5th Ave. with the lions) for helping me track down the SoHo Weekly News microfilm when it had apparently vanished, and to the professional staff at the New York Public Library for Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, and to the Fales Special Collections staff at Bobst Library at New York University. Special thanks to the much smaller archival operation at the Kitchen, where I was assisted at various times by John Migliore and Samara Davis. -

El Próximo Mes De Diciembre Inicia Bestia Festival

México D.F., martes 24 de noviembre de 2015 EL PRÓXIMO MES DE DICIEMBRE INICIA BESTIA FESTIVAL Se realizará en el Lunario y en el foro principal del Auditorio Nacional Otras actividades se llevarán a cabo en la Biblioteca Vasconcelos y en la SAE Institute México Este encuentro musical, que llega a su tercera edición, está curado por John Zorn Tendrá un cierre espectacular con un cine-concierto del filme El Gabinete del Dr. Caligari, con música en vivo del Órgano monumental del Auditorio El encuentro internacional de música BESTIA Festival, que se ha distinguido por programar a los artistas más representativos de la escena avant-garde, jazz, rock, hardcore y música experimental, con propuestas y grupos que difícilmente se presentan en otros escenarios de México, arrancará a principios de diciembre, realizándose por primera vez en el Auditorio Nacional y en su foro alterno el Lunario. La curaduría de la edición de este año del Festival, que presentará el Ciclo John Zorn México, estará a cargo de este influyente artista de la escena avant-garde en Nueva York. Si bien este festival fue creado por iniciativa de Estudio Paraíso y Volumen ACHE, desde su primera edición lo ha dirigido Claudia Curiel; y en esta ocasión el encuentro ampliará su programación con el apoyo del Auditorio Nacional, quien participa como coorganizador y sede de la edición 2015, en la que participarán más de 25 músicos nacionales e internacionales de primer nivel para interpretar repertorio de Masada así como propuestas de jazz, rock e improvisación. El concierto de apertura de la tercera edición de BESTIA Festival se realizará en la Biblioteca Vasconcelos el viernes 4 de diciembre, en el que participarán dos ensambles mexicanos, seleccionados por Zorn: Dora Juárez con “Cantos de una diáspora” y Micro- Ritmia de Ernesto Martínez “Sincronario”, quienes han grabado en la disquera del artista (Tzadik). -

The Kitchen Welcome's Back Avant-Garde Composer And

For Immediate Release January 20, 2015 THE KITCHEN WELCOME’S BACK AVANT-GARDE COMPOSER AND GUITARIST GLENN BRANCA TO PRESENT THE PREMIERE OF THE THIRD ASCENSION, FEBRUARY 23-24 Latest Development of Branca’s Influential 1981 Work The Ascension, Featuring Reg Bloor, Arad Evans and Owen Weaver The Kitchen welcomes back American avant-garde composer and guitarist Glenn Branca after more than twenty years for the premiere of The Third Ascension, a new work for guitar, bass, and drums. Conducted by Branca, this piece is the latest development of Branca’s influential 1981 work The Ascension, in which he experiments with resonances generated by alternate tunings for multiple electric guitars. Joining Branca will be Reg Bloor, Brendon Randall-Myers, Luke Schwartz and Arad Evans on guitar, Greg McMullen on bass, and Owen Weaver on drums. These shows will be recorded live for a subsequent album release. Artist Richard Prince has created a special poster for the concert, along with a limited-edition print. As a founder of the bands Theoretical Girls and Static in the seventies, Branca’s signature blend of hard rock with a contemporary music sensibility has earned him the title of "godfather of alternative rock." The importance of his music, particularly of The Ascension, is felt through the lasting impact it has made on its followers. In a 10.0-rated review of the album’s 2003 reissue, Pitchfork writes, “from these bloodied guitar strings and twisted metal carnage you can discern not just the euphoric guitar bliss of everyone from Sonic Youth to My Bloody Valentine, but also the mighty crescendos of Sigur Rós, Mogwai, Black Dice, Godspeed You Black Emperor!, or whomever, here executed with a plasma-like energy and melodic/harmonic structure still light-years beyond the forenamed.” The album has been called "one of the greatest rock albums ever made" (All Music) and “simply essential 20th-century music" (Tiny Mix Tapes).