A Critical Evaluation of the Public Consultation Process in Sustainable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Replacement of the St-Jacques Overpass Over the Decarie Expressway in Montreal

Replacement of the St-Jacques overpass over the Decarie expressway in Montreal Category: Transportation Presented to: Canadian Consulting Engineering Awards 2020 Cima+ | SNC-Lavalin inc. April 30, 2020 Table of Contents Context and Innovation 3 Complexity 5 Social and/or Economic Benefits 7 Environmental Benefits 9 Meeting Client’s Needs 11 2 | CIMA+ | SNC-Lavalin inc. | Canadian Consulting Engineering Awards | Category : Transportation CIMA+ | SNC-Lavalin inc. | Canadian Consulting Engineering Awards | Category : Transportation | 1 CONTEXT AND INNOVATION Located in the heart of Montreal, the original bridge on Saint-Jacques street was a rein- forced concrete structure built in 1967 that made it possible to cross the Décarie highway (A15). Although this structure was not at the end of its life, the location of the foundation elements was incompatible with the layout of the new Turcot interchange, forcing its re- DECK INSTALLATION placement. The location of the bridge also coincided with the Saint-Pierre collector buried BY LAUNCH in the ground. In order to replace the structure, the MTQ wanted a bridge with a strong architectural signature marking the entrance to downtown Montreal in this highly visible location from all directions. The selected structure is an asymmetrical cable-stayed bridge with two continuous spans, of 55 and 65 m long. The deck is an orthotropic box type with variable inertia, en- tirely made of steel. It is supported by 10 guy lines (5 per span) which are supported by a steel pylon with variable geometry having a height of 55 m. CONTEXT AND The structure was designed to allow an installation by launch. -

Projet De Remplacement Du Tablier Du Pont Honoré-Mercier

PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release Major Roadwork Blitzes at the Champlain Bridge Two Weekends in May Longueuil, May 3, 2016 – The Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges Incorporated (JCCBI) would like to advise road users that two major roadwork blitzes will take place at the Champlain Bridge in May. These blitzes will entail replacing 2 expansion joints and the repair of another expansion joint on the bridge’s deck, and thus result in complete closure to all traffic in one direction at a time. The work will be performed during the weekends of May 20-21 and 27-28, from Friday at 10 p.m. to Monday at 5 a.m. This roadwork is essential in order to avoid that water creep into cracks between lanes and damage some of the bridge’s structural members. Expansion joints fill the space between the bridge’s spans, which are mutually independent. They also enable traffic to flow safely, since they prevent discontinuity in the pavement. These blitzes will allow to complete various maintenance work operations and in some cases, contractors and other partners will also conduct work during these blitzes to keep additional lane road closures down to a minimum for users. BLITZ 1: Weekend of May 20-21 As part of this blitz, two expansion half-joints will be replaced on the Champlain Bridge’s upstream side, which will lead to the following road network restrictions: + Complete closure of the Champlain Bridge, toward the South Shore + Closure of Hwy. 15 South from the Turcot interchange down to Hwy. 132 + Closure of one out of three lanes on the Champlain Bridge towards Montreal + Closure of all access ramps to Hwy. -

2014-2024 Québec Infrastructure Plan Will Inject Fresh Vigour Into Major Road Projects, the Maritime Strategy and the Re-Launch of Plan Nord

The Québec Infrastructure Plan The desInfrastructure infrastructures Plan Papier 30 % fibres recyclées postconsommation, certifié Éco-Logo. Procédé sans chlore et fabriqué à partir d’énergie biogaz. Québec Infrastructure Plan 2014-2024 Legal Deposit - June 2014 Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec ISBN 978-2-550-70742-4 (Print Version) ISBN 978-2-550-70749-3 (Online) © Gouvernement du Québec - 2014 Message from the Chair of the Conseil du trésor Investments of $90.3 billion, managed responsibly and rigorously for the benefit of Quebecers and economic development Our government has committed to managing public infrastructures responsibly and rigorously to promote Québec’s economic growth while emphasizing choices that will ensure the sustainability of our real estate and road assets. As Chair of the Conseil du trésor, I aim to have public infrastructure investments meet the priority needs of the population, particulary for vulnerable client groups, while providing a powerful tool for economic development. In a context of rigorous public expenditure management, we have prioritized infrastructure projects that meet the following two criteria: A commitment to countering obsolescence and ensuring public safety The Government is announcing major investments needed to stop the deterioration of assets that are vital to delivering quality services to the population. Accordingly, over $50.6 billion has been allocated to the maintenance, repair and replacement of the entire portfolio of government assets, such as on the roads and in schools and hospitals. A commitment to economic development We are delivering on our commitment to economic development and job creation. Thus, the 2014-2024 Québec Infrastructure Plan will inject fresh vigour into major road projects, the Maritime Strategy and the re-launch of Plan Nord. -

April 11, 2017 C ROCHELLE CANTOR REAL ESTATE BROKER 514.605.6755 [email protected]

WESTMOUNT INDEPENDENT Weekly. Vol. 55 No. 7b We are Westmount April 55, 6458 Process outlined to replace Trent Y Masters turn (' Election of interim mayor set for April >? BF L9CA<<? SE<<?<F members during a special public council meeting April 24 at 7 pm in the council The wheels were set in motion April 3 to chamber. choose an interim mayor to replace Peter While this person is commonly known Trent. No sooner had he officially an - as an “interim mayor,” under the law this nounced that his resignation would take ef - person will be the mayor with full powers fect April 13 than a resolution declaring the and responsibilities of the office, city clerk position vacant was adopted. Martin St-Jean, director of Legal Services, It also stated the council would not pro - told the Independent last week. ceed to fill the vacancy through by-elec - This new mayor will serve until the gen - tion but by an option to elect one of their eral municipal elections throughout Que - bec on November 5. If the mayoralty is Photo: Martin C. Barry contested and the incumbent interim Westmount Page p. 16 mayor is re-elected, this person will simply The Westmount YMCA Masters swim team’s continue in the position. In the event that head coach Abdenour Hammadache, left, and only one person files to assistant coach Mohamad Alsabbagh are seen See: Letters p. 6 run for mayor and is a dif - continued on p. 19 with the team April H at the Y’s pool, where they • Trent’s swan song, p. -

TRANSFORMATION of the TURCOT YARDS 10 Things to Know About the New Nature-Park Project

TRANSFORMATION OF THE TURCOT YARDS 10 things to know about the new nature-park project August 2018 10 THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT THE NEW NATURE-PARK PROJECT IN THE TURCOT YARDS NEW NATURE-PARK IN THE TURCOT YARDS Ville de Montréal. (2018). Design vision for a new nature-park in the Saint-Jacques Escarpment Ecoterritory. 1 INTRODUCTION THE MUNICIPAL A NEW NATURE-PARK DEVELOPMENT VISION ON THE SITE OF THE 1 FORMER TURCOT RAIL YARDS The transfer of the autoroute northward, to the site of the former Turcot yard, will free up The Ville de Montréal will develop a completely Since this major park is to belong to citizens, a vast space between rue Notre-Dame and the new nature-park in the heart of the city, in the the municipal administration seeks to learn new highway. space freed up by reconstruction of the Turcot their aspirations with regard to the project. interchange. Located in the Saint-Jacques The Office de consultation publique de This newly vacant space offers a rare Escarpment Ecoterritory, this major park will Montréal will start the consultative process well opportunity to create a new green space. cover almost 30 hectares along 2 km. This ahead of the project’s realization. Subsequently, The major park project will provide numerous unique ecosystem offers a variety of landscapes various participatory activities will be deployed social, economic and environmental benefits — woods, wetland, prairie — and will allow for throughout the project development process. and will significantly improve quality of life the creation of a new green gateway to the city, for Montrealers. -

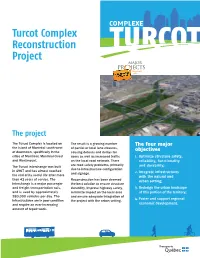

Turcot Complex Reconstruction Project

Turcot Complex Reconstruction Project The project The Turcot Complex is located on The result is a growing number The four major the Island of Montréal south-west of partial or total lane closures, objectives of downtown, specifically in the causing detours and delays for cities of Montréal, Montréal-Ouest users as well as increased traffic 1. Optimize structure safety, and Westmount. on the local road network. There reliability, functionality are road safety problems, primarily The Turcot interchange was built and durability; due to infrastructure configuration in 1967 and has almost reached and signage. 2. Integrate infrastructures the end of its useful life after more with the natural and than 41 years of service. The Reconstruction has been deemed urban setting; interchange is a major passenger the best solution to ensure structure and freight transportation axis, durability, improve highway safety, 3. Redesign the urban landscape and is used by approximately minimize impact on the local area of this portion of the territory; 280,000 vehicles per day. The and ensure adequate integration of 4. Foster and support regional infrastructures are in poor condition the project with the urban setting. and require an ever-increasing economic development. amount of repair work. Westmount Côte-des-Neiges / Montréal-Ouest Notre-Dame-de-Grâce Reconstruction of the Turcot Complex 15 includes: 720 • Reconstruction of the Turcot interchange; Lachine Rue oine Sai -Ant Montréal-Ouest nt- Saint es • Reconstruction of the de La Vérendrye Jacq Rue cqu ues -

Projet De Remplacement Du Tablier

PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release Major Roadwork Blitzes at the Champlain Bridge Two Weekends in May Longueuil, May 3, 2016 – The Jacques Cartier and Champlain Bridges Incorporated (JCCBI) would like to advise road users that two major roadwork blitzes will take place at the Champlain Bridge in May. These blitzes will entail replacing 2 expansion joints and the repair of 2 other expansion joints on the bridge’s deck, and thus result in complete closure to all traffic in one direction at a time. The work will be performed during the weekends of May 20-21 and 27-28, from Friday at 10 p.m. to Monday at 5 a.m. This roadwork is essential in order to avoid that water creep into cracks between lanes and damage some of the bridge’s structural members. Expansion joints fill the space between the bridge’s spans, which are mutually independent. They also enable traffic to flow safely, since they prevent discontinuity in the pavement. These blitzes will allow to complete various maintenance work operations and in some cases, contractors and other partners will also conduct work during these blitzes to keep additional lane road closures down to a minimum for users. BLITZ 1: Weekend of May 20-21 As part of this blitz, two expansion half-joints will be replaced on the Champlain Bridge’s upstream side, which will lead to the following road network restrictions: + Complete closure of the Champlain Bridge, towards the South Shore + Closure of Hwy. 15 South from the Turcot interchange down to Hwy. 132 + Closure of one out of three lanes on the Champlain Bridge towards Montreal + Closure of all access ramps to Hwy. -

Occupier's Guide

Montreal - Q4 2018 Occupier’s Guide Market Trends Vacancy Average Rent Net Absorption 11.8% $29.59/SF 75,354 SF Office: Class B buildings have been upgrading their common areas to attract tenants from It is an exciting time for the Montreal office and industrial markets. Foreign companies are the Class A- category who would gravitating to Montreal more than ever from all industries to benefit from low occupancy like to generate savings and keep costs, labor costs and an abundant talent pool. Overall, operating a business in the Greater their central location with close Montreal Area on average costs less than any other major metropolitan area in Canada and proximity to amenities and metro the US. As Canada’s university capital, Montreal is the home to 11 university institutions lines. with 320,000 post-secondary students and is currently considered the best city in the world for international students. Office: Coworking continues to be a growing trend in Montreal. There are also many incentive programs to entice foreign companies to open their WeWork has taken on an additional operations in the GMA for major projects and innovations with grants, interest free loans 20,000 SF at L’Avenue and Fabrik8 and other support available such as low electricity rates as low as US2.48c/kWh for large will be delivering up to 200 000 SF power. Labour development grants are also offered such as 25% of costs to implement in the Plateau of mixed co-working training programs and 50% of costs to create an HR Department. and office space in 2019. -

Expressway Aesthetics Montreal in the 1960S

e ssaY | essai Ex PrEssway aEsthEtics Montreal in the 1960s MgT Ar ArE E. HODgES is a Professor in > Margaret E. HodgeS the Department of Art History at Concordia University, Montreal. Her research focuses on Canadian architecture and urban planning, the work of women architects, and the aesthetics of architecture. n this paper I examine the Modern Iaesthetics of the urban expressway as it applies to the Turcot Complex in Montreal, built during the 1960s and early 1970s. The aesthetic value of the elevated expressway was understood in terms of its functionality, to ensure the smooth flow of traffic and the overall working of the city. The possibility of moving at high speeds was part of the aesthetic experience as it contributed to a new way of seeing the world. I argue that the Turcot Complex can be understood in terms of a functionalist aesthetics articu- lated in the urban theory of Blanche and Daniel van Ginkel of van Ginkel Associates, Montreal. I suggest that the phenomenological experience of the elevated expressway, when functioning as first designed, continues to express the positive qualities as articulated in the work of such perceptive theorists as Kevin Lynch in the 1960s. I compare the van Ginkels’ approach with what I call the green aesthetics of today’s approach to urban mobility in North American cities. Montreal is currently deciding on how to handle the deteriorating Turcot Complex and I look at some of the options being debated, including the levelling of the elevated system. In postwar North America, the cross-town expressway was considered a tool to solve the mobility problems of dense intercity traffic. -

Saint Raymond 2011 Baseline Report

Research Report SERIES DECEMBER 2012 RR12-02E Saint Raymond 2011 Baseline Study Kraemer, S., Merriman, J., Prince, J., Bornstein, L. School of Urban Planning, McGill University Abstract Saint-Raymond, a sub-neighbourhood of Notre-Dame-de-Grace and located just a few minutes West of downtown Montreal, lies immediately adjacent two megaprojects, the Turcot Interchange and the new McGill University Health Centre (MUHC). With a small and relatively stable residential population, Saint Raymond has a high proportion of non-Canadian-born residents. Th e neighbourhood is defi ned by signifi cant physical barriers, isolating it from other parts of the City, but these same factors may also have played a role in softening gentrifi cation pressures that have been strongly felt in surrounding areas. Th e arrival of the MUHC Glen Campus and the reconstruction of both the Décarie Expressway and the Turcot Interchange present a historic opportunity for the area to benefi t from changes going on around it and to improve connections with surrounding areas. Th is report paints a portrait of the neighbourhood and highlights the directions in which the neighbourhood may be headed. Cite as Kraemer, S., Merriman, J., Prince, J., Bornstein, L.(2012). “Saint Raymond 2011 Baseline Study”. Research Repot RR12-02E. Montréal: CURA Making Megaprojects Work for Communities - Mégaprojets au service es communautés. More reports and working papers at www.mcgill.ca/urbanplanning/mpc/research/ Community-University Research Alliance CURA } Alliance de recherche communauté-université L. Bornstein, Project Director — J. Prince, C. Vandermeulen, Project Coordinators School of Urban Planning Suite 400, Macdonald-Harrington Telephone: +1 (514) 398-4075 815 Sherbrooke Street West Fax: +1 (514) 398-8376 Montreal, Quebec H3A 2K6 www.mcgill.ca/urbanplanning/mpc Contents 1. -

The Westmount Historian PHOTOGRAPHY AS HISTORY

The Westmount Historian NEWSLETTER OF THE WESTMOUNT HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION VOLUME 10 NUMBER 2 FEBRUARY 2010 PHOTOGRAPHY AS HISTORY Cover photographs of Westmount c. 1890’s selected from Robert Harvie photographic album in WHA archives The Westmount Historian PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE NEWSLETTER OF THE WESTMOUNT believe that photographs present wonderful believable HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION Iimages of our history if we know how to look at them February 2010 and if we have enough of them. In this newsletter you Volume 10 • Number 2 will find photographs of lives lived at the end of the 1800s here in Westmount and surrounding areas. Most photo- EDITOR: graphs have been selected from the albums of two long Doreen Lindsay time Westmount families: the perfectly preserved James CONTRIBUTORS: Kewley Ward Family Album (he was mayor from 1873 to 1883 when West- Caroline Breslaw mount was a small area of the much larger Notre-Dame de Grace munici- Barbara Covington Doreen Lindsay pality) and the two Robert Harvie family albums which contain photographs made by Mr. Harvie himself in the late 1890s. Photos: WHA Archives Photos: pages 9, 10, 15 Notman Archives Of course, no account of photography in the Montreal area would be com- plete without a reference to William Notman, the well known Montreal WESTMOUNT HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION based, Scottish born professional photographer. William Notman’s photo- BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2009 – 2010 graphs of turn of the century life in Montreal provide a background and Doreen Lindsay, president context to the life of our two local families. Caroline Breslaw, vice-president We are including one of the 1971 photographs made by Brian Merrett and David Freeman, treasurer Anne Barkman, membership & website Jennifer Harper when they documented the demolition of homes on Selby Margarita Schultz, recording secretary Street during a period of destruction in the search for progress. -

The Westmount Historian

The Westmount Historian NEWSLETTEROFTHE WESTMOUNT HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION VOLUME 10 NUMBER 1 SEPTEMBER 2009 The Westmount Historian PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE NEWSLETTER OF THE WESTMOUNT If We had liVed here 100 Years ago We WoUld haVe HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION heard a cock crow in the morning and Watched farm- September 2009 ers ploW their fields betWeen the scattered hoUses Volume 10 • NUmber 1 along dirt roads. Fresh spring Water flowed down the hill from the children’s plaYgroUnd that We noW call EDITOR: Doreen Lindsay MUrraY Park. WestmoUnt Park Was a forest of trees With comfortable pathways along a deep ravine. If We CONTRIBUTORS: RUth Allan-RigbY looked Up We coUld see the feW large elegant Villas that doted oUr moUn- Caroline Breslaw tainside. We WoUld, of coUrse, Walk proUdlY on Wooden sideWalks along Barbara Covington neWlY opened macadamiZed streets. CommUnitY life Was actiVe. We Doreen Lindsay could read in the new free Public Library or attend a meeting in Victoria Photos: WHA Archives Hall. All our household necessities of milk, bread and ice Would be de- livered to our door bY horse and Wagon and We could enjoy shopping WESTMOUNT HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION for shoes, jeWelrY, or food aroUnd Greene AVenUe or if We liVed closer to BOARD OF DIRECTORS 2009 – 2010 Victoria Avenue, at the new large Biltcliffe department store. Doreen Lindsay, president We became a City 100 Years ago (1908) This newsletter combines the re- Caroline Breslaw, vice-president sUlt of siX months of research bY Caroline BreslaW, RUth Allan-RigbY and David Freeman, treasUrer mYself. RUth concentrates on mUnicipal serVices: the Police and Fire De- Anne Barkman, membership & Website Margarita Schultz, recording secretary partments, the CPR station, transport, the LibrarY and Victoria Hall.