Saudi Arabia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saudi Arabia.Pdf

A saudi man with his horse Performance of Al Ardha, the Saudi national dance in Riyadh Flickr / Charles Roffey Flickr / Abraham Puthoor SAUDI ARABIA Dec. 2019 Table of Contents Chapter 1 | Geography . 6 Introduction . 6 Geographical Divisions . 7 Asir, the Southern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �7 Rub al-Khali and the Southern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �8 Hejaz, the Western Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �8 Nejd, the Central Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 The Eastern Region � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 Topographical Divisions . .. 9 Deserts and Mountains � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �9 Climate . .. 10 Bodies of Water . 11 Red Sea � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Persian Gulf � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Wadis � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � 11 Major Cities . 12 Riyadh � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �12 Jeddah � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � �13 Mecca � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � � -

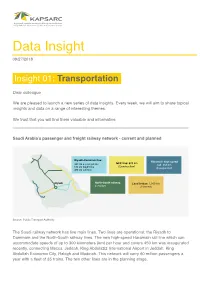

Data Insightsinsight 09/27/2018

DataData InsightsInsight 09/27/2018 Insight09/27/2018 01: Transportation Dear colleague We are pleased to launch a new series of data insights. Every week, we will aim to share topical insights and data on a range of interesting themes. We trust that you will find them valuable and informative. Saudi Arabia’s passenger and freight railway network - current and planned Riyadh-Dammam line: Haramain high speed GCC line: 28 km 449 km passenger line rail: 450 km (onstruction) 54 km freight line (Inaugurated) 400 km su-lines Riyadh North-South railway: Land bridge: 1,30 km 2,750 km (Planned) Source: Public Transport Authority The Saudi railway network has five main lines. Two lines are operational: the Riyadh to Dammam and the North-South railway lines. The new high-speed Haramain rail line which can accommodate speeds of up to 300 kilometers (km) per hour and covers 450 km was inaugurated recently, connecting Mecca, Jeddah, King Abdulaziz International Airport in Jeddah, King Abdullah Economic City, Rabigh and Madinah. This network will carry 60 million passengers a year with a fleet of 35 trains. The two other lines are in the planning stage. The existing North-South Railway project is one of the largest railway projects, covering more than 2,750 kilometers of track. It connects Riyadh and the northern border through the cities of Al-Qassim and Hail. The Riyadh to Dammam line was the first operational line: • The freight line opened in the 1950s, connecting King Abdulaziz Port in Dammam with Riyadh, through Al-Ahsa, Abqaiq, Al-Kharj, Haradh, and Al-Tawdhihiyah. -

Saudi Arabia. REPORT NO ISBN-0-93366-90-4 PUB DATE 90 NOTE 177P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 336 289 SO 021 184 AUTHOR McGregor, Joy; Nydell, Margaret TITLE Update: Saudi Arabia. REPORT NO ISBN-0-93366-90-4 PUB DATE 90 NOTE 177p. AVAILABLE FROM Intercultural Press, Inc., P.O. Box 700, Yarmouth, ME 04096 ($19.95, plus $2.00). PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Cultural Differences; Cultural Opportunities; *Foreign Countries; *Foreign Culture; Intercultural Communication; International Relations; Overseas Employment; Tourism; Travel IDENTIFIERS *Saudi Arabia ABSTRACT A guide for persons planning on living in or relocating to Saudi Arabia for extended periods of time, this book features information on such topics as entry requirements, transportation, money matters, housing, schools, and insurance. The guide's contents include the following sections: (1) an overview; (2) before leaving; (3) on arrival; (4) doing business; (5) customs and courtesies; (6) household pointers; (7) schools; (6) health and medical care; (9) leisure; (10) cities in profile; (11) sources of information; and (12) recommended readings. Three appendices are also included: (1) chambers of commerce and industry in Saudi Arabia; (2) average celsius temperatures of selected near eastern cities; and (3) prior to departure: recommended supplies. (DB) ***********************************************1!*********************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** U.S. DEPARTMENT OP EDUCATION Office of Educitional Research Ind Improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) ty,thls document has been reproduced Se Keived from the person or worn/aeon I (Quieting it O Minor changes Aare been made to improve reproduction Quality Points of view or opinions stated in this docu . -

Stranded Umrah Pilgrims Back in Kuwait After Harrowing Ordeal 52 Expats Stuck in Kingdom for 20 Days After Passports Go Missing from Hotel

SHAABAN 19, 1440 AH WEDNESDAY, APRIL 24, 2019 Max 31º 28 Pages Min 16º 150 Fils Established 1961 ISSUE NO: 17815 The First Daily in the Arabian Gulf www.kuwaittimes.net Stranded umrah pilgrims back in Kuwait after harrowing ordeal 52 expats stuck in kingdom for 20 days after passports go missing from hotel By Sajeev K Peter KUWAIT: Forty-four out of 52 umrah pilgrims from Kuwait, who were stranded in the holy city of Makkah after losing their passports and documents, returned to Kuwait yesterday. They had spent more than 20 traumatic days in the kingdom waiting for new travel documents. They arrived to a rousing welcome early yesterday, and were received at the border by police officers, office- bearers of the India Sunni Jamaat organization, volun- teers and relatives. However, eight of the pilgrims could not enter Kuwait as they only had exit passes and no passports, and had to go back to Makkah. According to sources, the tour oper- ators who took the pilgrims to the kingdom on umrah visas offered to help them complete their formalities and promised them air tickets to go back to their respective countries at the earliest. “We entered Kuwait around 6 o’clock in the morning, as we had to spend almost a day at the Kuwait-Saudi border because eight people in our group didn’t have passports,” said Razak Cheruthuruthy, one of the pilgrims. He said Kuwaiti officials had to KUWAIT: HH the Amir Sheikh Sabah Al-Ahmad Al-Jaber Al-Sabah presents the Amir Football Cup to captain of Kuwait SC Hussein Hakim and other players at Jaber Al-Ahmad resolve some technical problems, as they were entering International Stadium yesterday. -

Results from the Saudi Residents' Intention to Get Vaccinated

Article Attitudes toward the SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine: Results from the Saudi Residents’ Intention to Get Vaccinated against COVID-19 (SRIGVAC) Study Sami H. Alzahrani 1,* , Mukhtiar Baig 2 , Mohammed W. Alrabia 3, Mohammed R. Algethami 4 , Meshari M. Alhamdan 1, Nabil A. Alhakamy 5 , Hani Z. Asfour 3 and Tauseef Ahmad 6 1 Family Medicine Department, Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, P.O. Box 80205, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 3 Department of Medical Microbiology and Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] (M.W.A.); [email protected] (H.Z.A.) 4 Preventive Medicine and Public Health Resident, Ministry of Health, Jeddah 21577, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 5 Department of Pharmaceutics, Faculty of Pharmacy, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 6 Department of Epidemiology and Health Statistics, School of Public Health, Southeast University, Nanjing 210096, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +966-500004062 Abstract: Vaccine uptake could influence vaccination efforts to control the widespread COVID- Citation: Alzahrani, S.H.; Baig, M.; 19 pandemic; however, little is known about vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia. The present Alrabia, M.W.; Algethami, M.R.; study aimed to assess the Saudi public’s intent to get vaccinated against COVID-19 and explore Alhamdan, M.M.; Alhakamy, N.A.; the associated demographic determinants of their intentions as well as the reasons for vaccine Asfour, H.Z.; Ahmad, T. -

Communications and Information Technology Commission

Communications and Information Technology Commission Practical Information Event: Meeting of ITU-T Study Group 20 Regional Group for the Arab Region (SG20RG- ARB) and the fourteenth meeting of the Arab Standardization Team Host country: Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Location: Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Date: 7 October 2019 2 1 Location Riyadh is located on the Najd plateau in the centre of the Arabian Peninsula. It inhabits an area that geological studies refer to as the Arabian Shelf, characterized by its sedimentary rock, and is the capital city of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Today, with its strategic location, Riyadh is no more than a two hour-flight away for the entire population of the Arabian Peninsula. Increase the radius to a seven hour-flight and Riyadh becomes a viable market for more than half of the global population. This fact, along with Saudi Arabia’s significant population growth, has played a significant role in the economic growth, diversity and development in Riyadh, which, along with its surrounding areas, has been attracting unprecedented levels of local, national, regional and international investment. 1.1 King Khalid International Airport (RUH) Riyadh is served by the King Khalid International Airport, approximately 35 km to the north of the city, running flights to and from all corners of the globe, including cities in Europe, Asia and the Middle East. The airport has three main terminals: Terminals 1 and 2 serve international departures and arrivals; and Terminal 5 serves domestic flights. 1.2 Transport Riyadh has a safe, modern public transport network. In addition, there is a list of smart transport applications which have been approved by the public transport authority and can be downloaded onto smartphones. -

Visit Saudi Content Toolkit December 2020

Content Toolkit 1 Visit Saudi Content Toolkit December 2020 VisitSaudi.com Content Toolkit 2 This is your ‘Welcome to Arabia’ content toolkit. The purpose of this toolkit is to provide you with information, images and video to give you the support needed to create beautiful, inspiring, consistent content to promote Saudi as a destination around the world. The contents of this toolkit can be used to create powerful communications across print, social and online formats. Content Toolkit 3 A word from our CCO Dear Friends and Partners of the Saudi Tourism Authority, Saudi is the most exciting travel destination in the market today. Largely unexplored by international leisure visitors, Saudi is the true home of Arabia – a land rich in culture, heritage, mystique and romance. A land of adventure and unparalleled hospitality. Saudi is a study in contrasts. From Al Jouf in the north to Jazan in the south, you’ll find arid deserts and lush valleys, clear seas and rugged mountains, ancient archaeological sites and modern architecture, haute cuisine and street food. It is a country of natural beauty, great diversity and hidden treasures. Saudi’s tourism offering focuses on delivering authentically Arabian adventure, culture and heritage underpinned by remarkable hospitality. It is the Kingdom’s unique natural attributes and its authenticity as the home of Arabia that will attract and enthrall travelers. Saudi opened its doors and hearts to the world of leisure tourism in September 2019 with the launch of our tourism e-visa service. And before the global ban on international travel is response to the coronavirus pandemic, it was the fastest growing tourist destination in the world, according to the World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) Economic Impact Report. -

Profile of a Prince Promise and Peril in Mohammed Bin Salman’S Vision 2030

BELFER CENTER PAPER Profile of a Prince Promise and Peril in Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030 Karen Elliott House SENIOR FELLOW PAPER APRIL 2019 Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the author and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, the Harvard Kennedy School, or the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Design and layout by Andrew Facini Cover photo: Fans react as they watch the “Greatest Royal Rumble” event in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, Friday, April 27, 2018. (AP Photo/Amr Nabil) Copyright 2019, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America BELFER CENTER PAPER Profile of a Prince Promise and Peril in Mohammed bin Salman’s Vision 2030 Karen Elliott House SENIOR FELLOW PAPER APRIL 2019 About the Author Karen Elliott House is a senior fellow at the Belfer Center and author of On Saudi Arabia: Its People, Past, Religion, Fault Lines—and Future, published by Knopf in 2012. During a 32-year career at The Wall Street Journal she served as diplomatic correspondent, foreign editor, and finally as publisher of the paper. She won a Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting in 1984 for her coverage of the Middle East. She is chairman of the RAND Corporation. Her earlier Belfer Center reports on Saudi Arabia, “Saudi Arabia in Transition: From Defense to Offense, But How to Score?” (June 2017), and “Uneasy Lies the Head that Wears a Crown” (April 2016) can be found at www.belfercenter.org. -

The 2020 Vision of Saudi Arabia's Vision 2030

The 2020 Vision of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 Sebastian Meyer Karim Henide Director, Fixed Income Indices Associate, Fixed Income Indices Executive summary The early modern Kingdom of Saudi Arabia derived the greatest portion of its income from taxes relating to religious tourism (the Hajj to Mecca and Medina). Saudi Arabia’s income stream proved vulnerable in the wake of the Great Depression, where pilgrimage appetite declined precipitously. This highlighted the Kingdom’s need for an alternative source of wealth. Simultaneously, World War I had spotlighted the importance of hydrocarbons in future industrial development and military efforts1. Perceptively, the ruler and founder of the modern Kingdom, King Abdulaziz bin Abdul Rahman, initiated Saudi Arabia’s commercial exploration for oil. The upstream effort proved fruitful on 3rd March 1938, when a team from Standard Oil of California struck black gold in the desert bordering the Persian Gulf, establishing the Dammam oil well No. 7. The discovery was the beginning of a string of discoveries that signalled the beginning of an oil-focussed economy, with the Kingdom later founding the Ghawar mega field in 1948, the largest crude oil source in the world, constituting approximately a third of Saudi’s cumulative production today. Today, Saudi Arabia is undergoing yet another pivotal economic and social evolution. To support its ambitions, the Kingdom has begun to tap private and public markets for capital. Avenues for raising capital have included conventional debt markets, and the issuance of Sukuk- Sharia-compliant Islamic financial obligations. Saudi Arabia has been recently reappraised by several development institutions, seen its long-term sovereign credit rating ameliorate and maintained resilience of the US Dollar-pegged Saudi Riyal (SAR), which has been supportive of domestic and foreign investor confidence. -

Saudi Arabia's War with the Houthis: Old Borders, New Lines by Asher Orkaby

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 2404 Saudi Arabia's War with the Houthis: Old Borders, New Lines by Asher Orkaby Apr 9, 2015 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Asher Orkaby Asher Orkaby received his PhD in Middle East history from Harvard University and is currently a research fellow at the Crown Center for Middle East Studies. Brief Analysis Heeding fears over Iranian subversion and the security of the vital Bab al- Mandab Strait, the United States and other countries have been drawn into a longstanding Saudi-Yemeni dispute whose deep roots may not be fully appreciated. n its continued effort to undermine the Houthi tribal movement in Yemen through force of arms, Saudi Arabia I has managed to gather a growing alliance of Arab countries as well as logistical support from Turkey and the United States. Some have been surprised by the intervention's suddenness and the increasing ferocity of the air campaign, to which the number of Yemeni civilian casualties is a testament. Yet the latest military confrontation should not come as a surprise, since it occurs within the context of an eighty-year history of tensions between Riyadh and Yemen. Within one year of Saudi Arabia's emergence as a unified state in 1932, the Kingdom of Yemen had already declared war against its northern neighbor over a border dispute. Upon receiving a Saudi peace delegation in 1933, Imam Yahya, the king at the time, famously derided Ibn Saud, the founder of Saudi Arabia, by saying, "Who is this Bedouin coming to challenge my family's 900-year rule?" During the ensuing war, the Saudi Bedouin army managed to capture the Yemeni coastal region of Asir and the northernmost provinces of Najran and Jizan, but it was forced to halt the offensive on the capital city of Sana because its troops could not navigate the north's difficult mountainous terrain. -

Al-Badr Murabaha Fund in Saudi Riyals

Al-Badr Murabaha Fund in Saudi Riyals Open-End Shariah-Compliant Money Market Investment Fund. This is the amended version of the documents for Al-Badr Murabaha Fund in Saudi Riyals that reflects the following changes: • Update the names of the Board of Directors members with and type of membership According to our letter sent to the Capital Market Authority on Dhu al Hijah 26, 1442 AH, corresponding to August 05, 2021 AD. Contents: Terms and Conditions, Information Memorandum, Summary of Information Public Salam Zaki AlKhunaizi Nawwaf bin Zaben AlOtaibi Chief Executive Officer Chief Compliance, Governance and Legal Officer Terms and Conditions Al-Badr Murabaha Fund in Saudi Riyal An open-ended investment fund in a money market, subject to Islamic Shari’a. Al-Badr Murabaha Fund in Saudi riyals was approved as an investment fund that complies with Shari’a standards approved by the Shari’a Supervisory Committee appointed for the investment fund. The terms and conditions of the Al-Badr Murabaha Fund in Saudi Riyal and all other documents are subject to the investment funds regulations and encompass complete, clear, correct, non-misleading, updated and amended information. We advise investors to read the terms and conditions and other related documents of Al-Badr Murabaha Fund in Saudi Riyal, accurately and carefully and understand them before making any investment decision regarding the fund. In the event of lack clarity, financial advice should be sought from a financial adviser licensed by the Capital Market Authority to explain the following: a. The suitability of investing in the fund to achieve the investment goals b. -

Statistiken – Daten Und Analysen Q1-05

√ Oesterreichische Nationalbank Eurosystem Statistiken Daten & Analysen Q1/05 Die Quartalspublikation ªStatistiken — Daten & Analysen fokussiert ihre Berichte auf die o‹sterreichischen Finanzinstitutionen, Finanzstro‹me und Au§enwirtschaft. Der Tabellen- und Erla‹uterungsabschnitt deckt finanz- wirtschaftliche und realwirtschaftliche Indikatoren ab, die — erweitert — auch auf der OeNB-Website abrufbar sind. Schriftleitung Aurel Schubert, Gerhard Kaltenbeck, Eva-Maria Nesvadba Koordination Manfred Fluch, Irmgard Wenko Redaktion Karin Fischer, Susanne Pelz, Christiana Weinzetel Technische Gestaltung Peter Buchegger (Grafische Gestaltung) Hausdruckerei der OeNB (Layout, Satz, Druck und Herstellung) Ru‹ ckfragen Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Hauptabteilung Statistik/ Statistik Hotline oder Sekretariat des Direktoriums/O‹ffentlichkeitsarbeit Postanschrift: Postfach 61, 1011 Wien Telefon: Statistik Hotline (+43-1) 40420-5555 Sekretariat des Direktoriums/O‹ffentlichkeitsarbeit (+43-1) 40420-6666 Telefax: Statistik Hotline (+43-1) 40420-5499 Sekretariat des Direktoriums/O‹ffentlichkeitsarbeit (+43-1) 40420-6698 E-Mail: [email protected] und [email protected] Bestellungen/Adressenmanagement Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Dokumentationsmanagement und Kommunikationsservice Postanschrift: Postfach 61, 1011 Wien Telefon: (+43-1) 40420-2345 Telefax: (+43-1) 40420-2398 E-Mail: [email protected] Impressum Medieninhaber (Verleger), Herausgeber und Hersteller: Oesterreichische Nationalbank Otto-Wagner-Platz 3, 1090 Wien Gu‹nther Thonabauer,