Alternatives to Taxonomic Hierarchy: the Sahaptin Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

Field Bindweed (Convolvulus Arvensis): “All ” Tied Up

Weed Technology Field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis): “all ” www.cambridge.org/wet tied up Lynn M. Sosnoskie1 , Bradley D. Hanson2 and Lawrence E. Steckel3 1 2 Intriguing World of Weeds Assistant Professor, School of Integrative Plant Science, Cornell University, Geneva, NY USA; Cooperative Extension Specialist, Department of Plant Science, University of California – Davis, Davis, CA, USA and 3 Cite this article: Sosnoskie LM, Hanson BD, Professor, Department of Plant Sciences, University of Tennessee, Jackson, TN, USA Steckel LE (2020) Field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis): “all tied up”. Weed Technol. 34: 916–921. doi: 10.1017/wet.2020.61 Received: 22 March 2020 Revised: 2 June 2020 But your snobbiness, unless you persistently root it out like the bindweed it is, sticks by you till your Accepted: 4 June 2020 grave. – George Orwell First published online: 16 July 2020 The real danger in a garden came from the bindweed. That moved underground, then surfaced and took hold. Associate Editor: Strangling plant after healthy plant. Killing them all, slowly. And for no apparent reason, except that it was Jason Bond, Mississippi State University nature. – Louise Penny Author for correspondence: Lynn M. Sosnoskie, Cornell University, 635 W. Introduction North Avenue, Geneva, NY 14456. (Email: [email protected]) Field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis L.) is a perennial vine in the Convolvulaceae, or morning- glory family, which includes approximately 50 to 60 genera and more than 1,500 species (Preston 2012a; Stefanovic et al. 2003). The family is in the order Solanales and is characterized by alternate leaves (when present) and bisexual flowers that are 5-lobed, folded/pleated in the bud, and trumpet-shaped when emerged (Preston 2012a; Stefanovic et al. -

Birding Tour South Africa: Western Cape Custom Tour

BIRDING TOUR SOUTH AFRICA: WESTERN CAPE CUSTOM TOUR 8-12 OCTOBER 2016 By Chris Lotz Orange-breasted Sunbird (photo John Tinkler) www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | T R I P R E P O R T Western Cape custom tour October 2016 ITINERARY Date (2016) Location Overnight 8-Oct Cape Town to Tankwa Karoo Sothemba Lodge, Tankwa 9-Oct Full day in the Karoo Sothemba Lodge, Tankwa 10-Oct Tankwa Karoo to the Overberg Mudlark River Front Lodge 11-Oct Agulhas Plains Mudlark River Front Lodge 12-Oct Betty's Bay and Rooiels (back in Cape Town) Day 1: 8 October 2016 I fetched Robert and Elizabeth from Hotel Verde at Cape Town International Airport at 7:30 a.m., and we immediately started heading toward the amazingly endemic-rich Tankwa Karoo. But we had lots of birding to do before getting to the Karoo. En route we stopped in the famous Cape wine town of Paarl for an hour or two, as Paarl boasts some excellent birding sites and is perfectly right on the way to the Karoo. Just as we entered Paarl we were glad to be able to stop for a pale-phase Booted Eagle soaring above us – we actually ended up seeing a good number of this small eagle throughout our tour. After admiring the eagle we headed for the botanical garden within the Paarl Mountain Nature Reserve, where we got acquainted with a bunch of fynbos endemics and other goodies. This trip proved excellent for raptors. As we arrived at the botanical garden, we saw a Black Harrier hunting, then later we got amazingly close views of a perched African Goshawk – a two-accipiter morning is always a good morning! Three species of beautiful sunbirds were much in evidence: Malachite, Southern Double-collared, and Orange-breasted Sunbirds. -

Namibia & the Okavango

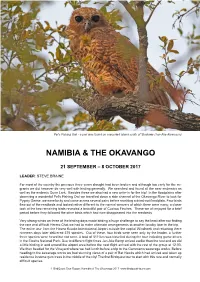

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

Bonner Zoologische Beiträge

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Bonn zoological Bulletin - früher Bonner Zoologische Beiträge. Jahr/Year: 2004 Band/Volume: 52 Autor(en)/Author(s): Adler Kraig Artikel/Article: America's First Herpetological Expedition: William Bartram's Travels in Southeastern United States (1773-1776) 275-295 © Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.zoologicalbulletin.de; www.biologiezentrum.at Bonner zoologische Beiträge Band 52 (2003) Heft 3/4 Seiten 275-295 Bonn, November 2004 America's First Herpetological Expedition: William Bartram's Travels in Southeastern United States (1773-1776) Kraig Adler Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA. Abstract. William Bartram (1739-1823), author of the epic Travels Through North & South Carolina. Georgia, East & West Florida (1791), was the first native-born American naturalist to gain international recognition. He was trained by his father - John Bartram, King George Ill's "Royal Botanist in North America" - who took him on his first ex- pedition at the age of 14. Although William, too, was primarily a botanist, he developed a special interst in turtles. He visited Florida in 1765-1767 and North Carolina in 1761-1762 and 1770-1772. William Bartram's expedition of 1773-1776, through eight southeastern colonies, was undertaken with the patronage of British sponsors. It began on the eve of America's War of Independence but, when the Revolutionary War com- menced in 1775, it became America's first herpetological (and natural history) survey. At least 40 different kinds of amphibians and reptiles are recorded in "Bartram's Travels", most of them identifiable to species. -

Recerca I Territori V12 B (002)(1).Pdf

Butterfly and moths in l’Empordà and their response to global change Recerca i territori Volume 12 NUMBER 12 / SEPTEMBER 2020 Edition Graphic design Càtedra d’Ecosistemes Litorals Mediterranis Mostra Comunicació Parc Natural del Montgrí, les Illes Medes i el Baix Ter Museu de la Mediterrània Printing Gràfiques Agustí Coordinadors of the volume Constantí Stefanescu, Tristan Lafranchis ISSN: 2013-5939 Dipòsit legal: GI 896-2020 “Recerca i Territori” Collection Coordinator Printed on recycled paper Cyclus print Xavier Quintana With the support of: Summary Foreword ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Xavier Quintana Butterflies of the Montgrí-Baix Ter region ................................................................................................................. 11 Tristan Lafranchis Moths of the Montgrí-Baix Ter region ............................................................................................................................31 Tristan Lafranchis The dispersion of Lepidoptera in the Montgrí-Baix Ter region ...........................................................51 Tristan Lafranchis Three decades of butterfly monitoring at El Cortalet ...................................................................................69 (Aiguamolls de l’Empordà Natural Park) Constantí Stefanescu Effects of abandonment and restoration in Mediterranean meadows .......................................87 -

Ecology and Management of Field Bindweed (Convolvulus Arvensis

United States Department of Agriculture NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE Invasive Species Technical Note No. MT-9 February 2007 Ecology and Management of field bindweed [Convolvulus arvensis L.] by Jim Jacobs, NRCS Invasive Species Specialist, Bozeman, Montana Figure 1. Field bindweed forms mats of trailing, twining vines. Abstract Field bindweed is a persistent perennial weed in the Convolvulaceae taxonomic family found on cultivated fields, orchards, plantations, pastures, lawns, gardens, roadsides and along railways. It is listed as one of the ten most serious weed problems worldwide. Its extensive, competitive root system is capable of vegetative reproduction. This combined with long-lived seeds makes it difficult to manage. Dense tangled mats formed from the trailing vines, and vines climbing on crops, reduce crop yields and increase production costs. Over 500 seeds per plant can be produced from the funnel-shaped flowers. Field bindweed is native to the Mediterranean region and was first recorded in the United States in 1739. In Montana, it was first collected in 1891 from Missoula County near the University of Montana, and by 2001 it had been reported from all Montana Counties except Richland and Fallon (http://invader.dbs.umt.edu). Propagules of field bindweed migrate as contaminants of crop seed and hay, when attached to farming equipment, and they have been intentionally introduced as ornamental or medicinal plants. Once established, field bindweed will persist after most control applications. However, the leaves are not shade tolerant and competitive plants will suppress field bindweed and reduce its seed production. On croplands, frequent cultivations will reduce root reserves; however infestations can increase under no-till or reduced till management. -

ELEMENT STEWARDSHIP ABSTRACT for Convolvulus Arvensis L. Field Bindweed to the User: Element Stewardship Abstracts (Esas) Are Pr

1 ELEMENT STEWARDSHIP ABSTRACT for Convolvulus arvensis L. Field Bindweed To the User: Element Stewardship Abstracts (ESAs) are prepared to provide The Nature Conservancy's Stewardship staff and other land managers with current management related information on those species and communities that are most important to protect, or most important to control. The abstracts organize and summarize data from numerous sources including literature and researchers and managers actively working with the species or community. We hope, by providing this abstract free of charge, to encourage users to contribute their information to the abstract. This sharing of information will benefit all land managers by ensuring the availability of an abstract that contains up-to-date information on management techniques and knowledgeable contacts. Contributors of information will be acknowledged within the abstract. For ease of update and retrievability, the abstracts are stored on computer. Anyone with comments, questions, or information on current or past monitoring, research, or management programs for the species described in this abstract is encouraged to contact The Nature Conservancy’s Wildland Weeds Management and Research Program. This abstract is a compilation of available information and is not an endorsement of particular practices or products. Please do not remove this cover statement from the attached abstract. Author of this Abstract: Kelly E. Lyons Evolution and Ecology, University of California at Davis. THE NATURE CONSERVANCY 4245 North Fairfax Drive, Arlington, Virginia 22203-1606 (703) 841-5300 2 SPECIES CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME Convolvulus arvensis L. Convolvulus is derived from the Latin, convolere, meaning to entwine, and arvensis means ‘of fields’ (Gray, 1970). -

The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation

M DC, — _ CO ^. E CO iliSNrNVINOSHilWS' S3ldVyan~LIBRARlES*"SMITHS0N!AN~lNSTITUTl0N N' oCO z to Z (/>*Z COZ ^RIES SMITHSONIAN_INSTITUTlON NOIiniIiSNI_NVINOSHllWS S3ldVaan_L: iiiSNi'^NviNOSHiiNS S3iavyan libraries Smithsonian institution N( — > Z r- 2 r" Z 2to LI ^R I ES^'SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTlON'"NOIini!iSNI~NVINOSHilVMS' S3 I b VM 8 11 w </» z z z n g ^^ liiiSNi NviNOSHims S3iyvyan libraries Smithsonian institution N' 2><^ =: to =: t/J t/i </> Z _J Z -I ARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHilWS SSIdVyan L — — </> — to >'. ± CO uiiSNi NViNosHiiws S3iyvaan libraries Smithsonian institution n CO <fi Z "ZL ~,f. 2 .V ^ oCO 0r Vo^^c>/ - -^^r- - 2 ^ > ^^^^— i ^ > CO z to * z to * z ARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIinillSNl NVINOSHllWS S3iaVdan L to 2 ^ '^ ^ z "^ O v.- - NiOmst^liS^> Q Z * -J Z I ID DAD I re CH^ITUCnMIAM IMOTtTIITinM / c. — t" — (/) \ Z fj. Nl NVINOSHIIINS S3 I M Vd I 8 H L B R AR I ES, SMITHSONlAN~INSTITUTION NOIlfl :S^SMITHS0NIAN_ INSTITUTION N0liniliSNI__NIVIN0SHillMs'^S3 I 8 VM 8 nf LI B R, ^Jl"!NVINOSHimS^S3iavyan"'LIBRARIES^SMITHS0NIAN~'lNSTITUTI0N^NOIin L '~^' ^ [I ^ d 2 OJ .^ . ° /<SS^ CD /<dSi^ 2 .^^^. ro /l^2l^!^ 2 /<^ > ^'^^ ^ ..... ^ - m x^^osvAVix ^' m S SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION — NOIlfliliSNrNVINOSHimS^SS iyvyan~LIBR/ S "^ ^ ^ c/> z 2 O _ Xto Iz JI_NVIN0SH1I1/MS^S3 I a Vd a n^LI B RAR I ES'^SMITHSONIAN JNSTITUTION "^NOlin Z -I 2 _j 2 _j S SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIinillSNI NVINOSHilWS S3iyVaan LI BR/ 2: r- — 2 r- z NVINOSHiltNS ^1 S3 I MVy I 8 n~L B R AR I Es'^SMITHSONIAN'iNSTITUTIOn'^ NOlin ^^^>^ CO z w • z i ^^ > ^ s smithsonian_institution NoiiniiiSNi to NviNosHiiws'^ss I dVH a n^Li br; <n / .* -5^ \^A DO « ^\t PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY ENTOMOLOGIST'S RECORD AND Journal of Variation Edited by P.A. -

Convolvulus Arvensis

Species: Convolvulus arvensis http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/forb/conarv/all.html SPECIES: Convolvulus arvensis Choose from the following categories of information. Introductory Distribution and occurrence Botanical and ecological characteristics Fire ecology Fire effects Management considerations References INTRODUCTORY SPECIES: Convolvulus arvensis AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION FEIS ABBREVIATION SYNONYMS NRCS PLANT CODE COMMON NAMES TAXONOMY LIFE FORM FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS OTHER STATUS ©Barry A. Rice/The Nature Conservancy AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION: Zouhar, Kris. 2004. Convolvulus arvensis. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2007, September 24]. FEIS ABBREVIATION: CONARV SYNONYMS: None 1 of 48 9/24/2007 4:13 PM Species: Convolvulus arvensis http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/forb/conarv/all.html NRCS PLANT CODE [111]: COAR4 COMMON NAMES: field bindweed field morning-glory morning glory small bindweed devil's guts TAXONOMY: The currently accepted name for field bindweed is Convolvulus arvensis L. It is a member of the morning-glory family (Convolvulaceae) [30,37,50,54,60,64,70,71,81,88,96,110,145,146,149,153]. LIFE FORM: Vine-forb FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS: No special status OTHER STATUS: As of this writing (2004), field bindweed is classified as a noxious or prohibited weed or weed seed in 35 states in the U.S. and 5 Canadian provinces [139]. See the Invaders, Plants, or APHIS databases for more information. The Eastern Region of the U.S. Forest Service ranks field bindweed as a Category 3 plant: often restricted to disturbed ground and not especially invasive in undisturbed natural habitats [136]. -

Coleoptera: Lampyridae)

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2020-03-23 Advances in the Systematics and Evolutionary Understanding of Fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) Gavin Jon Martin Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Life Sciences Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Martin, Gavin Jon, "Advances in the Systematics and Evolutionary Understanding of Fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae)" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 8895. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/8895 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Advances in the Systematics and Evolutionary Understanding of Fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) Gavin Jon Martin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Seth M. Bybee, Chair Marc A. Branham Jamie L. Jensen Kathrin F. Stanger-Hall Michael F. Whiting Department of Biology Brigham Young University Copyright © 2020 Gavin Jon Martin All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Advances in the Systematics and Evolutionary Understanding of Fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) Gavin Jon Martin Department of Biology, BYU Doctor of Philosophy Fireflies are a cosmopolitan group of bioluminescent beetles classified in the family Lampyridae. The first catalogue of Lampyridae was published in 1907 and since that time, the classification and systematics of fireflies have been in flux. Several more recent catalogues and classification schemes have been published, but rarely have they taken phylogenetic history into account. Here I infer the first large scale anchored hybrid enrichment phylogeny for the fireflies and use this phylogeny as a backbone to inform classification. -

South Africa Mega Birding III 5Th to 27Th October 2019 (23 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Mega Birding III 5th to 27th October 2019 (23 days) Trip Report The near-endemic Gorgeous Bushshrike by Daniel Keith Danckwerts Tour leader: Daniel Keith Danckwerts Trip Report – RBT South Africa – Mega Birding III 2019 2 Tour Summary South Africa supports the highest number of endemic species of any African country and is therefore of obvious appeal to birders. This South Africa mega tour covered virtually the entire country in little over a month – amounting to an estimated 10 000km – and targeted every single endemic and near-endemic species! We were successful in finding virtually all of the targets and some of our highlights included a pair of mythical Hottentot Buttonquails, the critically endangered Rudd’s Lark, both Cape, and Drakensburg Rockjumpers, Orange-breasted Sunbird, Pink-throated Twinspot, Southern Tchagra, the scarce Knysna Woodpecker, both Northern and Southern Black Korhaans, and Bush Blackcap. We additionally enjoyed better-than-ever sightings of the tricky Barratt’s Warbler, aptly named Gorgeous Bushshrike, Crested Guineafowl, and Eastern Nicator to just name a few. Any trip to South Africa would be incomplete without mammals and our tally of 60 species included such difficult animals as the Aardvark, Aardwolf, Southern African Hedgehog, Bat-eared Fox, Smith’s Red Rock Hare and both Sable and Roan Antelopes. This really was a trip like no other! ____________________________________________________________________________________ Tour in Detail Our first full day of the tour began with a short walk through the gardens of our quaint guesthouse in Johannesburg. Here we enjoyed sightings of the delightful Red-headed Finch, small numbers of Southern Red Bishops including several males that were busy moulting into their summer breeding plumage, the near-endemic Karoo Thrush, Cape White-eye, Grey-headed Gull, Hadada Ibis, Southern Masked Weaver, Speckled Mousebird, African Palm Swift and the Laughing, Ring-necked and Red-eyed Doves.