ELEMENT STEWARDSHIP ABSTRACT for Convolvulus Arvensis L. Field Bindweed to the User: Element Stewardship Abstracts (Esas) Are Pr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks Bioblitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 ON THIS PAGE Photograph of BioBlitz participants conducting data entry into iNaturalist. Photograph courtesy of the National Park Service. ON THE COVER Photograph of BioBlitz participants collecting aquatic species data in the Presidio of San Francisco. Photograph courtesy of National Park Service. The 2014 Golden Gate National Parks BioBlitz - Data Management and the Event Species List Achieving a Quality Dataset from a Large Scale Event Natural Resource Report NPS/GOGA/NRR—2016/1147 Elizabeth Edson1, Michelle O’Herron1, Alison Forrestel2, Daniel George3 1Golden Gate Parks Conservancy Building 201 Fort Mason San Francisco, CA 94129 2National Park Service. Golden Gate National Recreation Area Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1061 Sausalito, CA 94965 3National Park Service. San Francisco Bay Area Network Inventory & Monitoring Program Manager Fort Cronkhite, Bldg. 1063 Sausalito, CA 94965 March 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Report Series is used to disseminate comprehensive information and analysis about natural resources and related topics concerning lands managed by the National Park Service. -

Convolvulaceae1

Photograph: Helen Owens © Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources, Government of South Australia Department of All rights reserved Environment, Copyright of illustrations might reside with other institutions or Water and individuals. Please enquire for details. Natural Resources Contact: Dr Jürgen Kellermann Editor, Flora of South Australia (ed. 5) State Herbarium of South Australia PO Box 2732 Kent Town SA 5071 Australia email: [email protected] Flora of South Australia 5th Edition | Edited by Jürgen Kellermann CONVOLVULACEAE1 R.W. Johnson2 Annual or perennial herbs or shrubs, often with trailing or twining stems, or leafless parasites; leaves alternate, exstipulate. Inflorescence axillary, rarely terminal, cymose or reduced to a single flower; flowers regular, (4) 5 (6)-merous, bisexual; sepals free or rarely united, quincuncial; corolla sympetalous, funnel-shaped or campanulate, occasionally rotate or salver-shaped; stamens adnate to the base of the corolla, alternating with the corolla lobes, filaments usually flattened and dilated downwards; anthers 2-celled, dehiscing longitudinally; ovary superior, mostly 2-celled, occasionally with 1, 3 or 4 cells, subtended by a disk; ovules 2, rarely 1, in each cell; styles 1 or 2, stigmas variously shaped. Fruit capsular. About 58 genera and 1,650 species mainly tropical and subtropical; in Australia 20 genera, 1 endemic, with c. 160 species, 17 naturalised. The highly modified parasitic species of Cuscuta are sometimes placed in a separate family, the Cuscutaceae. 1. Yellowish leafless parasitic twiners ...................................................................................................................... 5. Cuscuta 1: Green leafy plants 2. Ovary distinctly 2-lobed; styles 2, inserted between the lobes of ovary (gynobasic style); leaves often kidney-shaped ............................................................................................................. -

PLUME MOTHS of AFGHANISTAN (LEPIDOPTERA, PTEROPHORIDAE) 1Altai State University, Lenina 61

Biological Bulletin of Bogdan Chmelnitskiy Melitopol State Pedagogical University 183 UDC 595.7(262.81) Peter Ustjuzhanin,1,6* Vasily Kovtunovich,2 Igor Pljushtch,3 Juriy Skrylnik4, Oleg Pak5 PLUME MOTHS OF AFGHANISTAN (LEPIDOPTERA, PTEROPHORIDAE) 1Altai State University, Lenina 61. RF-656049. Barnaul, Russia. 2 Moscow Society of Nature Explorers. Home address: Russia, Moscow, 121433, Malaya Filevskaya str., 24/1, app. 20. 3Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology, National Academy of Science of Ukraine, Bogdan Khmielnitski str., 15, 01601, Kiev, Ukraine. 4 Ukrainian Research Institute of Forestry & Forest Melioration, 61024, Pushkinska str. 86, Kharkov, Ukraine. 5 Donetsk National University, Faculty of Biology, Shchors str., 46, 83050, Donetsk, Ukraine. 6*Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] New data on Pterophoridae from Afghanistan are considered. A checklist of Pterophoridae species of the fauna of Afghanistan is presented, as including 32 species of 14 genera. Merrifieldia tridactyla is for the first time recorded for the fauna of Afghanistan. The basic literature on the Afghanistan Pterophoridae were used in the study. Key words: Pterophoridae, plume moths, Afghanistan, fauna, new data. INTRODUCTION Many Pterophoridae as Cossidae are specific inhabitants of the arid regions of the Palaearctic. Usually deserts are good zoogeographical barriers preventing from mixing the faunas of different zoogeographical regions (Yakovlev & Dubatolov 2013; Yakovlev, 2015; Yakovlev et al., 2015). Until now there were no special publications on Pterophoridae from Afghanistan. The first description of a new species of Pterophoridae, Stenoptilia nurolhaki, from Afghanistan was in the work by Amsel (1967), In a series of works by Ernst Arenberger (1981, 1987, 1995), six new species were described from Afghanistan. -

Field Bindweed (Convolvulus Arvensis): “All ” Tied Up

Weed Technology Field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis): “all ” www.cambridge.org/wet tied up Lynn M. Sosnoskie1 , Bradley D. Hanson2 and Lawrence E. Steckel3 1 2 Intriguing World of Weeds Assistant Professor, School of Integrative Plant Science, Cornell University, Geneva, NY USA; Cooperative Extension Specialist, Department of Plant Science, University of California – Davis, Davis, CA, USA and 3 Cite this article: Sosnoskie LM, Hanson BD, Professor, Department of Plant Sciences, University of Tennessee, Jackson, TN, USA Steckel LE (2020) Field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis): “all tied up”. Weed Technol. 34: 916–921. doi: 10.1017/wet.2020.61 Received: 22 March 2020 Revised: 2 June 2020 But your snobbiness, unless you persistently root it out like the bindweed it is, sticks by you till your Accepted: 4 June 2020 grave. – George Orwell First published online: 16 July 2020 The real danger in a garden came from the bindweed. That moved underground, then surfaced and took hold. Associate Editor: Strangling plant after healthy plant. Killing them all, slowly. And for no apparent reason, except that it was Jason Bond, Mississippi State University nature. – Louise Penny Author for correspondence: Lynn M. Sosnoskie, Cornell University, 635 W. Introduction North Avenue, Geneva, NY 14456. (Email: [email protected]) Field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis L.) is a perennial vine in the Convolvulaceae, or morning- glory family, which includes approximately 50 to 60 genera and more than 1,500 species (Preston 2012a; Stefanovic et al. 2003). The family is in the order Solanales and is characterized by alternate leaves (when present) and bisexual flowers that are 5-lobed, folded/pleated in the bud, and trumpet-shaped when emerged (Preston 2012a; Stefanovic et al. -

Oregon City Nuisance Plant List

Nuisance Plant List City of Oregon City 320 Warner Milne Road , P.O. Box 3040, Oregon City, OR 97045 Phone: (503) 657-0891, Fax: (503) 657-7892 Scientific Name Common Name Acer platanoides Norway Maple Acroptilon repens Russian knapweed Aegopodium podagraria and variegated varieties Goutweed Agropyron repens Quack grass Ailanthus altissima Tree-of-heaven Alliaria officinalis Garlic Mustard Alopecuris pratensis Meadow foxtail Anthoxanthum odoratum Sweet vernalgrass Arctium minus Common burdock Arrhenatherum elatius Tall oatgrass Bambusa sp. Bamboo Betula pendula lacinata Cutleaf birch Brachypodium sylvaticum False brome Bromus diandrus Ripgut Bromus hordeaceus Soft brome Bromus inermis Smooth brome-grasses Bromus japonicus Japanese brome-grass Bromus sterilis Poverty grass Bromus tectorum Cheatgrass Buddleia davidii (except cultivars and varieties) Butterfly bush Callitriche stagnalis Pond water starwort Cardaria draba Hoary cress Carduus acanthoides Plumeless thistle Carduus nutans Musk thistle Carduus pycnocephalus Italian thistle Carduus tenufolius Slender flowered thistle Centaurea biebersteinii Spotted knapweed Centaurea diffusa Diffuse knapweed Centaurea jacea Brown knapweed Centaurea pratensis Meadow knapweed Chelidonium majou Lesser Celandine Chicorum intybus Chicory Chondrilla juncea Rush skeletonweed Cirsium arvense Canada Thistle Cirsium vulgare Common Thistle Clematis ligusticifolia Western Clematis Clematis vitalba Traveler’s Joy Conium maculatum Poison-hemlock Convolvulus arvensis Field Morning-glory 1 Nuisance Plant List -

Recerca I Territori V12 B (002)(1).Pdf

Butterfly and moths in l’Empordà and their response to global change Recerca i territori Volume 12 NUMBER 12 / SEPTEMBER 2020 Edition Graphic design Càtedra d’Ecosistemes Litorals Mediterranis Mostra Comunicació Parc Natural del Montgrí, les Illes Medes i el Baix Ter Museu de la Mediterrània Printing Gràfiques Agustí Coordinadors of the volume Constantí Stefanescu, Tristan Lafranchis ISSN: 2013-5939 Dipòsit legal: GI 896-2020 “Recerca i Territori” Collection Coordinator Printed on recycled paper Cyclus print Xavier Quintana With the support of: Summary Foreword ......................................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Xavier Quintana Butterflies of the Montgrí-Baix Ter region ................................................................................................................. 11 Tristan Lafranchis Moths of the Montgrí-Baix Ter region ............................................................................................................................31 Tristan Lafranchis The dispersion of Lepidoptera in the Montgrí-Baix Ter region ...........................................................51 Tristan Lafranchis Three decades of butterfly monitoring at El Cortalet ...................................................................................69 (Aiguamolls de l’Empordà Natural Park) Constantí Stefanescu Effects of abandonment and restoration in Mediterranean meadows .......................................87 -

The Chemical Constituents and Pharmacological Effects of Convolvulus Arvensis and Convolvulus Scammonia- a Review

IOSR Journal Of Pharmacy www.iosrphr.org (e)-ISSN: 2250-3013, (p)-ISSN: 2319-4219 Volume 6, Issue 6 Version. 3 (June 2016), PP. 64-75 The chemical constituents and pharmacological effects of Convolvulus arvensis and Convolvulus scammonia- A review Prof Dr Ali Esmail Al-Snafi Department of Pharmacology, College of Medicine, Thi qar University, Nasiriyah, P O Abstract:The phytochemical studies showed that Convolvulus arvensis contained alkaloids, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, carbohydrates, sugars, mucilage, sterols, resin. tannins, unsaturated sterols/triterpenes, lactones and proteins; while, scammonia contained scammonin resin, dihydroxy cinnamic acid, beta-methyl- esculetin, ipuranol, surcose, reducing sugar and starch. The previous pharmacological studies revealed that Convolvulus arvensis possessed cytotoxic, antioxidant, vasorelaxat, immunostimulant, epatoprotective, antibacterial, antidiarrhoeal and diuretic effect; while, Convolvulus scammonia sowed purgative , vasorelaxat, anti platelet aggregation, anticancer and cellular protective effects. This study will highlight the constituents and pharmacological effects of Convolvulus arvensis and Convolvulus scammonia. Keywords: constituents, pharmacology, Convolvulus arvensis, Convolvulus scammonia. I. INTRODUCTION: Herbal medicine is the oldest form of medicine known to mankind. It was the mainstay of many early civilizations and still the most widely practiced form of medicine in the world today. Plant showed wide range of pharmacological activities including antimicrobial, antioxidant, -

Ecology and Management of Field Bindweed (Convolvulus Arvensis

United States Department of Agriculture NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION SERVICE Invasive Species Technical Note No. MT-9 February 2007 Ecology and Management of field bindweed [Convolvulus arvensis L.] by Jim Jacobs, NRCS Invasive Species Specialist, Bozeman, Montana Figure 1. Field bindweed forms mats of trailing, twining vines. Abstract Field bindweed is a persistent perennial weed in the Convolvulaceae taxonomic family found on cultivated fields, orchards, plantations, pastures, lawns, gardens, roadsides and along railways. It is listed as one of the ten most serious weed problems worldwide. Its extensive, competitive root system is capable of vegetative reproduction. This combined with long-lived seeds makes it difficult to manage. Dense tangled mats formed from the trailing vines, and vines climbing on crops, reduce crop yields and increase production costs. Over 500 seeds per plant can be produced from the funnel-shaped flowers. Field bindweed is native to the Mediterranean region and was first recorded in the United States in 1739. In Montana, it was first collected in 1891 from Missoula County near the University of Montana, and by 2001 it had been reported from all Montana Counties except Richland and Fallon (http://invader.dbs.umt.edu). Propagules of field bindweed migrate as contaminants of crop seed and hay, when attached to farming equipment, and they have been intentionally introduced as ornamental or medicinal plants. Once established, field bindweed will persist after most control applications. However, the leaves are not shade tolerant and competitive plants will suppress field bindweed and reduce its seed production. On croplands, frequent cultivations will reduce root reserves; however infestations can increase under no-till or reduced till management. -

Hungary in Summer

Hungary in Summer Naturetrek Tour Report 9 – 16 August 2016 Keeled Skimmer by Clive Pickton Crested Lark by Gerard Gorman Geometrician by Paul Harmes White-tailed Skimmer by Clive Pickton Report by Gerard Gorman & Paul Harmes. Images by Gerard Gorman, Clive Pickton & Paul Harmes Mingledown Barn Wolf’s Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Hungary in Summer Tour Leaders: Paul Harmes (leader), Gerard Gorman(Local Guide & Tour manager & Driver: Norbert With eight Naturetrek clients Day 1 Tuesday 9th August Fly Heathrow to Budapest – Transfer to the Kiskunsag.Area Eight group members met with Paul at London’s Heathrow, Terminal 3 for the 8.50am British Airways flight BA866 to Budapest Ferenc Liszt International (formerly Ferihegy) Airport. On arrival we completed immigration formalities, collected our luggage and made our way to the arrivals hall where we were met by Gerard, our local guide, and Norbert, our driver for the week. Before very long, Norbert had loaded our luggage into the bus, and we were on our way south towards the Kiskunsag National Park. After about an hour we passed through the village of Bugyi, making a stop to see nesting White Stork. Moving on south, we recorded Red-backed Shrike, Common Kestrel and Western Marsh Harrier, before stopping at country store at Szittyourbo. Here we had a snack lunch and local coffee, and got our first look at this sandy habitat. Essex Skipper, Meadow Brown and Chestnut Heath butterflies were seen, as well as Straw Belle and Rose-banded Wave moths. -

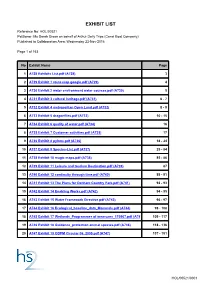

Exhibit List

EXHIBIT LIST Reference No: HOL/00521 Petitioner: Ms Sarah Green on behalf of Arthur Daily Trips (Canal Boat Company) Published to Collaboration Area: Wednesday 23-Nov-2016 Page 1 of 163 No Exhibit Name Page 1 A728 Exhibits List.pdf (A728) 3 2 A729 Exhibit 1 route map google.pdf (A729) 4 3 A730 Exhibit 2 water environment water courses.pdf (A730) 5 4 A731 Exhibit 3 cultural heritage.pdf (A731) 6 - 7 5 A732 Exhibit 4 metropolitan Open Land.pdf (A732) 8 - 9 6 A733 Exhibit 5 dragonflies.pdf (A733) 10 - 15 7 A734 Exhibit 6 quality of water.pdf (A734) 16 8 A735 Exhibit 7 Customer activities.pdf (A735) 17 9 A736 Exhibit 8 pylons.pdf (A736) 18 - 24 10 A737 Exhibit 9 Species-List.pdf (A737) 25 - 84 11 A738 Exhibit 10 magic maps.pdf (A738) 85 - 86 12 A739 Exhibit 11 Leisure and tourism Destination.pdf (A739) 87 13 A740 Exhibit 12 continuity through time.pdf (A740) 88 - 91 14 A741 Exhibit 13 The Plans for Denham Country Park.pdf (A741) 92 - 93 15 A742 Exhibit 14 Enabling Works.pdf (A742) 94 - 95 16 A743 Exhibit 15 Water Framework Directive.pdf (A743) 96 - 97 17 A744 Exhibit 16 Ecological_baseline_data_Mammals.pdf (A744) 98 - 108 18 A745 Exhibit 17 Wetlands_Programmes of measures_170907.pdf (A745) 109 - 117 19 A746 Exhibit 18 Guidance_protection animal species.pdf (A746) 118 - 136 20 A747 Exhibit 19 ODPM Circular 06_2005.pdf (A747) 137 - 151 HOL/00521/0001 EXHIBIT LIST Reference No: HOL/00521 Petitioner: Ms Sarah Green on behalf of Arthur Daily Trips (Canal Boat Company) Published to Collaboration Area: Wednesday 23-Nov-2016 Page 2 of 163 No Exhibit -

The Entomologist's Record and Journal of Variation

M DC, — _ CO ^. E CO iliSNrNVINOSHilWS' S3ldVyan~LIBRARlES*"SMITHS0N!AN~lNSTITUTl0N N' oCO z to Z (/>*Z COZ ^RIES SMITHSONIAN_INSTITUTlON NOIiniIiSNI_NVINOSHllWS S3ldVaan_L: iiiSNi'^NviNOSHiiNS S3iavyan libraries Smithsonian institution N( — > Z r- 2 r" Z 2to LI ^R I ES^'SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTlON'"NOIini!iSNI~NVINOSHilVMS' S3 I b VM 8 11 w </» z z z n g ^^ liiiSNi NviNOSHims S3iyvyan libraries Smithsonian institution N' 2><^ =: to =: t/J t/i </> Z _J Z -I ARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIiniliSNI NVINOSHilWS SSIdVyan L — — </> — to >'. ± CO uiiSNi NViNosHiiws S3iyvaan libraries Smithsonian institution n CO <fi Z "ZL ~,f. 2 .V ^ oCO 0r Vo^^c>/ - -^^r- - 2 ^ > ^^^^— i ^ > CO z to * z to * z ARIES SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIinillSNl NVINOSHllWS S3iaVdan L to 2 ^ '^ ^ z "^ O v.- - NiOmst^liS^> Q Z * -J Z I ID DAD I re CH^ITUCnMIAM IMOTtTIITinM / c. — t" — (/) \ Z fj. Nl NVINOSHIIINS S3 I M Vd I 8 H L B R AR I ES, SMITHSONlAN~INSTITUTION NOIlfl :S^SMITHS0NIAN_ INSTITUTION N0liniliSNI__NIVIN0SHillMs'^S3 I 8 VM 8 nf LI B R, ^Jl"!NVINOSHimS^S3iavyan"'LIBRARIES^SMITHS0NIAN~'lNSTITUTI0N^NOIin L '~^' ^ [I ^ d 2 OJ .^ . ° /<SS^ CD /<dSi^ 2 .^^^. ro /l^2l^!^ 2 /<^ > ^'^^ ^ ..... ^ - m x^^osvAVix ^' m S SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION — NOIlfliliSNrNVINOSHimS^SS iyvyan~LIBR/ S "^ ^ ^ c/> z 2 O _ Xto Iz JI_NVIN0SH1I1/MS^S3 I a Vd a n^LI B RAR I ES'^SMITHSONIAN JNSTITUTION "^NOlin Z -I 2 _j 2 _j S SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION NOIinillSNI NVINOSHilWS S3iyVaan LI BR/ 2: r- — 2 r- z NVINOSHiltNS ^1 S3 I MVy I 8 n~L B R AR I Es'^SMITHSONIAN'iNSTITUTIOn'^ NOlin ^^^>^ CO z w • z i ^^ > ^ s smithsonian_institution NoiiniiiSNi to NviNosHiiws'^ss I dVH a n^Li br; <n / .* -5^ \^A DO « ^\t PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY ENTOMOLOGIST'S RECORD AND Journal of Variation Edited by P.A. -

Convolvulus Arvensis

Species: Convolvulus arvensis http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/forb/conarv/all.html SPECIES: Convolvulus arvensis Choose from the following categories of information. Introductory Distribution and occurrence Botanical and ecological characteristics Fire ecology Fire effects Management considerations References INTRODUCTORY SPECIES: Convolvulus arvensis AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION FEIS ABBREVIATION SYNONYMS NRCS PLANT CODE COMMON NAMES TAXONOMY LIFE FORM FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS OTHER STATUS ©Barry A. Rice/The Nature Conservancy AUTHORSHIP AND CITATION: Zouhar, Kris. 2004. Convolvulus arvensis. In: Fire Effects Information System, [Online]. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory (Producer). Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/ [2007, September 24]. FEIS ABBREVIATION: CONARV SYNONYMS: None 1 of 48 9/24/2007 4:13 PM Species: Convolvulus arvensis http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/forb/conarv/all.html NRCS PLANT CODE [111]: COAR4 COMMON NAMES: field bindweed field morning-glory morning glory small bindweed devil's guts TAXONOMY: The currently accepted name for field bindweed is Convolvulus arvensis L. It is a member of the morning-glory family (Convolvulaceae) [30,37,50,54,60,64,70,71,81,88,96,110,145,146,149,153]. LIFE FORM: Vine-forb FEDERAL LEGAL STATUS: No special status OTHER STATUS: As of this writing (2004), field bindweed is classified as a noxious or prohibited weed or weed seed in 35 states in the U.S. and 5 Canadian provinces [139]. See the Invaders, Plants, or APHIS databases for more information. The Eastern Region of the U.S. Forest Service ranks field bindweed as a Category 3 plant: often restricted to disturbed ground and not especially invasive in undisturbed natural habitats [136].