What Is Sphagnum Peat Moss and Where Does It Come From?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drosera Intermedia in a Northern Michigan Bog

Assessment of microhabitat differences between Drosera rotundifolia and Drosera intermedia in a northern Michigan bog Andrew David University of Michigan Biological Station EEB 381, General Ecology August 19, 2010 Professor Cathy Bach Abstract The purpose of this study was to investigate microhabitat differences between two species of sundews, Drosera rotundifolia and Drosera intermedia. I tested several hypotheses: D. rotundifolia density increases with increasing height above a fixed low point, while D. intermedia density decreases with height; D. rotundifolia grows primarily on red Sphagnum moss, while D. intermedia grows primarily on green Sphagnum; the densities of both Drosera species increase with decreasing pH; the density of neither Drosera species is affected by water conductivity or dissolved oxygen content. At Mud Lake Bog in Cheboygan County, Michigan, I recorded the species of Drosera plants, as well as the height of the plants above a fixed low point and the color of Sphagnum moss on which they were growing. I also measured the pH, conductivity, and dissolved oxygen content of the water in which the plants were growing. Densities of both Drosera species decreased with increasing height, though the trend was stronger for D. intermedia. D. rotundifolia grew significantly more on red Sphagnum than did D. intermedia, while D. intermedia grew significantly more on green Sphagnum than did D. rotundifolia. D. rotundifolia density varied significantly with neither pH, conductivity, nor dissolved oxygen. D. intermedia density increased significantly with decreasing pH and increasing conductivity, but not with dissolved oxygen. My results were consistent with past research, and conclusively illustrated the differences in microhabitat preferences between the two Drosera species. -

Ferns Robert H

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Illustrated Flora of Illinois Southern Illinois University Press 10-1999 Ferns Robert H. Mohlenbrock Southern Illinois University Carbondale Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/siupress_flora_of_illinois Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Mohlenbrock, Robert H., "Ferns" (1999). Illustrated Flora of Illinois. 3. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/siupress_flora_of_illinois/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Southern Illinois University Press at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illustrated Flora of Illinois by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF ILLINOIS ROBERT H. MOHLENBROCK, General Editor THE ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF ILLINOIS s Second Edition Robert H. Mohlenbrock SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY PRESS Carbondale and Edwardsville COPYRIGHT© 1967 by Southern Illinois University Press SECOND EDITION COPYRIGHT © 1999 by the Board of Trustees, Southern Illinois University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 02 01 00 99 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mohlenbrock, Robert H., 1931- Ferns I Robert H. Mohlenbrock. - 2nd ed. p. em.- (The illustrated flora of Illinois) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Ferns-Illinois-Identification. 2. Ferns-Illinois-Pictorial works. 3. Ferns-Illinois-Geographical distribution-Maps. 4. Botanical illustration. I. Title. II. Series. QK525.5.I4M6 1999 587'.3'09773-dc21 99-17308 ISBN 0-8093-2255-2 (cloth: alk. paper) CIP The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.§ This book is dedicated to Miss E. -

Controlling the Invasive Moss Sphagnum Palustre at Ka'ala

Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI`I AT MĀNOA Dr. David C. Duffy, Unit Leader Department of Botany 3190 Maile Way, St. John #408 Honolulu, Hawai’i 96822 Technical Report 192 Controlling the invasive moss Sphagnum palustre at Ka‘ala, Island of O‘ahu March 2015 Stephanie Marie Joe 1 1 The Oahu Army Natural Resource Program (OANRP) USAG-HI, Directorate of Public Works Environmental Division IMPC-HI-PWE 947 Wright Ave., Wheeler Army Airfield, Schofield Barracks, HI 96857-5013 [email protected] PCSU is a cooperative program between the University of Hawai`i and U.S. National Park Service, Cooperative Ecological Studies Unit. Organization Contact Information: Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit, Department of Botany, 3190 Maile Way, St. John #408, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, HI 96822. Office: (808) 753-0702. Recommended Citation: Joe, SM. 2015. Controlling the invasive moss Sphagnum palustre at Ka‘ala, Island of O‘ahu. Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit Technical Report 191. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Department of Botany. Honolulu, HI. 18 pages. Key words: Bryocides, Sphagnum palustre, invasive species control Place key words: Pacific islands, O‘ahu, Ka‘ala Natural Area Reserve Editor: David C. Duffy, PCSU Unit Leader (Email: [email protected]) Series Editor: Clifford W. Morden, PCSU Deputy Director (Email: [email protected]) About this technical report series: This technical report series began in 1973 with the formation of the Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa. In 2000, it continued under the Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit (PCSU). The series currently is supported by the PCSU. -

<I>Sphagnum</I> Peat Mosses

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/evo.12547 Evolution of niche preference in Sphagnum peat mosses Matthew G. Johnson,1,2,3 Gustaf Granath,4,5,6 Teemu Tahvanainen, 7 Remy Pouliot,8 Hans K. Stenøien,9 Line Rochefort,8 Hakan˚ Rydin,4 and A. Jonathan Shaw1 1Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina 27708 2Current Address: Chicago Botanic Garden, 1000 Lake Cook Road Glencoe, Illinois 60022 3E-mail: [email protected] 4Department of Plant Ecology and Evolution, Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University, Norbyvagen¨ 18D, SE-752 36, Uppsala, Sweden 5School of Geography and Earth Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada 6Department of Aquatic Sciences and Assessment, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SE-750 07, Uppsala, Sweden 7Department of Biology, University of Eastern Finland, P.O. Box 111, 80101, Joensuu, Finland 8Department of Plant Sciences and Northern Research Center (CEN), Laval University Quebec, Canada 9Department of Natural History, Norwegian University of Science and Technology University Museum, Trondheim, Norway Received March 26, 2014 Accepted September 23, 2014 Peat mosses (Sphagnum)areecosystemengineers—speciesinborealpeatlandssimultaneouslycreateandinhabitnarrowhabitat preferences along two microhabitat gradients: an ionic gradient and a hydrological hummock–hollow gradient. In this article, we demonstrate the connections between microhabitat preference and phylogeny in Sphagnum.Usingadatasetof39speciesof Sphagnum,withan18-locusDNAalignmentandanecologicaldatasetencompassingthreelargepublishedstudies,wetested -

Ecological and Genetic Status of the Purple Pitcher Plant, <I>Sarracenia

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Biological Sciences Theses & Dissertations Biological Sciences Spring 2010 Ecological and Genetic Status of the Purple Pitcher Plant, Sarracenia purpurea L., in Maryland and Virginia Philip M. Sheridan Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/biology_etds Part of the Botany Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, and the Plant Biology Commons Recommended Citation Sheridan, Philip M.. "Ecological and Genetic Status of the Purple Pitcher Plant, Sarracenia purpurea L., in Maryland and Virginia" (2010). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), dissertation, Biological Sciences, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/wmzf-ca05 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/biology_etds/78 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ECOLOGICAL AND GENETIC STATUS OF THE PURPLE PITCHER PLANT, SARRACENIA PURPUREA L., IN MARYLAND AND VIRGINIA by Philip M. Sheridan B.S. Biology, May 1994, Virginia Commonwealth University M.S. Biology, August 1996, Virginia Commonwealth University A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ECOLOGICAL SCIENCES OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY May 2010 Dr. Frame Day (Director Dr. Kneeland Nesius (Member) Dr. LyTEon Musselman (Member) ABSTRACT ECOLOGICAL AND GENETIC STATUS OF THE PURPLE PITCHER PLANT, SARRACENIA PURPUREA L., IN MARYLAND AND VIRGINIA Philip M. Sheridan Old Dominion University, 2010 Director: Dr. Frank Day Sarraceniapurpurea is a rare wetland plant in Virginia and a threatened species in Maryland, with two potential subspecies in the region. -

Fragrant Annuals Fragrant Annuals

TheThe AmericanAmerican GARDENERGARDENER® TheThe MagazineMagazine ofof thethe AAmericanmerican HorticulturalHorticultural SocietySociety JanuaryJanuary // FebruaryFebruary 20112011 New Plants for 2011 Unusual Trees with Garden Potential The AHS’s River Farm: A Center of Horticulture Fragrant Annuals Legacies assume many forms hether making estate plans, considering W year-end giving, honoring a loved one or planting a tree, the legacies of tomorrow are created today. Please remember the American Horticultural Society when making your estate and charitable giving plans. Together we can leave a legacy of a greener, healthier, more beautiful America. For more information on including the AHS in your estate planning and charitable giving, or to make a gift to honor or remember a loved one, please contact Courtney Capstack at (703) 768-5700 ext. 127. Making America a Nation of Gardeners, a Land of Gardens contents Volume 90, Number 1 . January / February 2011 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 5 NOTES FROM RIVER FARM 6 MEMBERS’ FORUM 8 NEWS FROM THE AHS 2011 Seed Exchange catalog online for AHS members, new AHS Travel Study Program destinations, AHS forms partnership with Northeast garden symposium, registration open for 10th annual America in Bloom Contest, 2011 EPCOT International Flower & Garden Festival, Colonial Williamsburg Garden Symposium, TGOA-MGCA garden photography competition opens. 40 GARDEN SOLUTIONS Plant expert Scott Aker offers a holistic approach to solving common problems. 42 HOMEGROWN HARVEST page 28 Easy-to-grow parsley. 44 GARDENER’S NOTEBOOK Enlightened ways to NEW PLANTS FOR 2011 BY JANE BERGER 12 control powdery mildew, Edible, compact, upright, and colorful are the themes of this beating bugs with plant year’s new plant introductions. -

Sphagnum Moss As Growing Medium in Phalaenopsis Orchid

Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci (2019) 8(2): 2118-2123 International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Sciences ISSN: 2319-7706 Volume 8 Number 02 (2019) Journal homepage: http://www.ijcmas.com Original Research Article https://doi.org/10.20546/ijcmas.2019.802.245 Sphagnum Moss as Growing Medium in Phalaenopsis Orchid M.M. Kaveriamma1*, P.K. Rajeevan2, D. Girija2 and K. Nandini2 1DST Young Scientist University of Agricultural and Horticultural Sciences College of Forestry, Kodagu, India 2Kerala Agricultural University College of Horticulture, Kerala, India *Corresponding author ABSTRACT Phalaenopsis orchids occupy a top position in the international market as pot plant. Commonly used media for growing Phalaenopsis orchid are coconut husk chips, tree bark, fir bark, cocopeat and sphagnum moss. Growing medium is important as it provides K e yw or ds anchorage, retains moisture, nutrients and aerates the roots. In addition to these functions, a study was carried out to assess the possible growth promoting effects of sphagnum moss Phalaenopsis on orchids when used as growing medium. Eight month old hardened plants of Orchid, Klebsiella Phalaenopsis ‘Magic Kiss’ were used for the trial. They were planted in translucent plastic pneumoniae, Wilt, pots with three different growing media viz., coarse coconut husk chips, cocopeat (fine Moss coconut husk bits) and sphagnum moss in combination with charcoal and tile bits. Plants Article Info grown in sphagnum moss were significantly superior to those grown in coconut husk chips and coconut husk bits as media, both in terms of vegetative and floral attributes. Root cross Accepted: section of sphagnum moss grown plants revealed healthy velamen and their root 15 January 2019 Available Online: parenchyma tissues were rich in chlorophyll. -

Physical Growing Media Characteristics of Sphagnum Biomass Dominated by Sphagnum Fuscum (Schimp.) Klinggr

Physical growing media characteristics of Sphagnum biomass dominated by Sphagnum fuscum (Schimp.) Klinggr. A. Kämäräinen1, A. Simojoki2, L. Lindén1, K. Jokinen3 and N. Silvan4 1 Department of Agricultural Sciences, University of Helsinki, Finland 2 Department of Food and Environmental Sciences, University of Helsinki, Finland 3 Natural Resources Institute Finland, Natural Resources and Bioproduction, Helsinki, Finland 4 Natural Resources Institute Finland, Bio-based Business and Industry, Parkano, Finland _______________________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY The surface biomass of moss dominated by Sphagnum fuscum (Schimp.) Klinggr. (Rusty Bog-moss) was harvested from a sparsely drained raised bog. Physical properties of the Sphagnum moss were determined and compared with those of weakly and moderately decomposed peats. Water retention curves (WRC) and saturated hydraulic conductivities (Ks) are reported for samples of Sphagnum moss with natural structure, as well as for samples that were cut to selected fibre lengths or compacted to different bulk densities. The gravimetric water retention results indicate that, on a dry mass basis, Sphagnum moss can hold more water than both types of peat under equal matric potentials. On a volumetric basis, the water retention of Sphagnum moss can be linearly increased by compacting at a gravimetric water content of 2 (g water / g dry mass). The bimodal water retention curve of Sphagnum moss appears to be a consequence of the natural double porosity of the moss matrix. The 6-parameter form of the double-porosity van Genuchten equation is used to describe the volumetric water retention of the moss as its bulk density increases. Our results provide considerable insight into the physical growing media properties of Sphagnum moss biomass. -

Inventory of Rare Bryophytes in Unique Wetland Ecosystems on the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest

Inventory of Rare Bryophytes in Unique Wetland Ecosystems on the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest Photo: L. Wilson 2010 U.S.D.A Forest Service Region 6 and U.S.D.I Bureau of Land Management Interagency Special Status and Sensitive Species Program Authors Clint Emerson is a botanist, USDA Forest Service, Rogue River Siskiyou National Forest, Gold Beach and Powers Ranger Districts, Gold Beach, OR 97465 Scot Loring is a botanist, Pacific Crest Consulting, LLC, Talent, OR 97540 Introduction The Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest (RRSNF) dissects a geographically diverse area of Oregon, creating a high level of endemism with regard to vascular plants. At this point much less is known about non-vascular plant diversity in the region so botanists on the forest proposed a project to inventory unique wetland ecosystems for Region 6 Sensitive, Strategic and Oregon Biologic Information Center (ORBIC) list 3 and 4 bryophytes (mosses, liverworts and hornworts). The project received funding from the Interagency Special Status and Sensitive Species Program (ISSSSP) for field work to begin during the 2009 field season. This report summarizes findings of the inventory. Wetland ecosystems are an uncommon feature of the steep and highly dissected Siskiyou Mountains in Southwest Oregon. They are dispersed more so within the Southern Oregon Cascade portion of the forest, but are still considered an uncommon feature on the landscape when compared to unique upland ecosystems such as prairies or rock outcrops. In comparison to northwestern Oregon and western Washington little information exists with regard to Sensitive wetland associated bryophytes in southwest Oregon. This may be due to the fact that large metropolitan areas with universities are mostly lacking from the region and therefore the expertise and funding to accomplish this type of work is not as available. -

Drosera Capensis (Cape Sundew) Propagation by Leaf Cutting Video Summary Chlöe Fackler PLNT 310, April 7Th, 2017

Drosera capensis (Cape Sundew) Propagation by Leaf Cutting Video Summary Chlöe Fackler PLNT 310, April 7th, 2017 Sundew Natural History Sundews (Drosera spp.) are carnivorous plants in the family Droseraceae, which also contains the genus Dionaea (Venus Flytrap) and Aldrovanda (Waterwheel) (Lloyd, 1942). They employ a sweet and sticky nectar, secreted from the tentacles (trichomes) on their leaves, to trap insects (Finnie and van Staden, 1993). They then curl the leaf to completely encapsulate their prey, and digest it using a variety of enzymes. The reason for their carnivorous nature is to supplement their growth in mineral-poor media with nitrogen and other nutrients extracted from their prey. In particular, D. capensis, the Cape Sundew, is a species of subtropical sundew native to the cape of South Africa (Brittnacher, n.d.). It can be propagated by seed, and Cape Sundew (Drosera capensis) Plants in the Raymond Greenhouse by leaf, root, and inflorescence cuttings, as well as in vitro using micropropagation. Growing it is also fairly simple, requiring a moist, salt-free medium of peat/sand and sphagnum, and significant light. Objective To determine the effectiveness of different media and the use of Stimroot No. 1 rooting powder (IBA 0.1 mgL-1) on the growth of Drosera capensis (Cape Sundew) from leaf cuttings Procedure View the corresponding video for step-by-step instructions on how to conduct this experiment, or propagate sundews by leaf cuttings in general. Required Materials • Healthy Drosera capensis specimens • Scissors • Isopropanol (for sterilizing) • Sphagnum • Distilled water • Containers with holes (for growing the cuttings in sphagnum moss) • Containers without holes (for growing the cuttings in distilled water) • Seedling flats • Flat covers -1 • Stimroot No. -

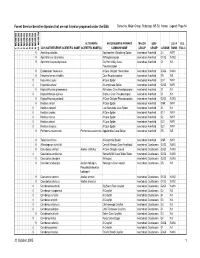

Sensitive Species That Are Not Listed Or Proposed Under the ESA Sorted By: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci

Forest Service Sensitive Species that are not listed or proposed under the ESA Sorted by: Major Group, Subgroup, NS Sci. Name; Legend: Page 94 REGION 10 REGION 1 REGION 2 REGION 3 REGION 4 REGION 5 REGION 6 REGION 8 REGION 9 ALTERNATE NATURESERVE PRIMARY MAJOR SUB- U.S. N U.S. 2005 NATURESERVE SCIENTIFIC NAME SCIENTIFIC NAME(S) COMMON NAME GROUP GROUP G RANK RANK ESA C 9 Anahita punctulata Southeastern Wandering Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G4 NNR 9 Apochthonius indianensis A Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1G2 N1N2 9 Apochthonius paucispinosus Dry Fork Valley Cave Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 Pseudoscorpion 9 Erebomaster flavescens A Cave Obligate Harvestman Invertebrate Arachnid G3G4 N3N4 9 Hesperochernes mirabilis Cave Psuedoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G5 N5 8 Hypochilus coylei A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G3? NNR 8 Hypochilus sheari A Lampshade Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 NNR 9 Kleptochthonius griseomanus An Indiana Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Kleptochthonius orpheus Orpheus Cave Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 9 Kleptochthonius packardi A Cave Obligate Pseudoscorpion Invertebrate Arachnid G2G3 N2N3 9 Nesticus carteri A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid GNR NNR 8 Nesticus cooperi Lost Nantahala Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1 N1 8 Nesticus crosbyi A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G1? NNR 8 Nesticus mimus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2 NNR 8 Nesticus sheari A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR 8 Nesticus silvanus A Cave Spider Invertebrate Arachnid G2? NNR -

How to Grow Carnivorous Plants in Skagit Valley

How to Grow Carnivorous Plants in Skagit Valley By Anita Reetz December 9, 2016 An easy job under proper conditions Carnivorous plants can be attractive additions to home gardens here in Skagit Valley provided you supply proper soil, water and light conditions. Soil Peat is the most important ingredient in the mix. It is produced in a swampy area where plants and trees are decaying in an acidic, anaerobic environment. Water, especially moving water, dissolves minerals in the soil. What’s left can be just rock, gravel, pumice and/or sand. At the Discovery Garden, we use sphagnum peat and vermiculite or perlite when we mix the soil. Sphagnum peat can hold more than ten times its weight in water. It is very acidic with a pH of 3- 5 (a neutral acid-alkaline balance is 7). When buying, be sure sphagnum appears with the word peat on the packaging. Sphagnum peat, washed sand, vermiculite and perlite are available locally at most farm and garden stores. At the Discovery Garden after much research and trial and error, we have arrived at the following mix ratios: Pitcher plants and cobras—1:1 ratio of sphagnum peat to perlite, vermiculite or sand Sundews and Venus flytraps— 2:1 ratio of sphagnum peat to perlite, vermiculite or sand (Washed sand can also substitute for half the perlite or vermiculite at a 1:1 ratio) Use a plastic tub or wheelbarrow for mixing, depending on the number of plants. A 6”-8” flower pot works well for measuring. Break up any peat clumps to create a fluffy, airy consistency.