International Conference on Turkey , the Kurds and the EU

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity, Narrative and Frames: Assessing Turkey's Kurdish Initiatives

ARTICLE IDENTITY, NARRATIVE AND FRAMES: ASSESSING TURKEY’S KURDISH INITIATIVES Identity, Narrative and Frames: Assessing Turkey’s Kurdish Initiatives JOHANNA NYKÄNEN* ABSTRACT In 2009 the Turkish government launched a novel initiative to tackle the Kurdish question. The initiative soon ran into deadlock, only to be un- tangled towards the end of 2012 when a new policy was announced. This comparative paper adopts Michael Barnett’s trinity of identity, narratives and frames to show how a cultural space within which a peaceful engage- ment with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) would be deemed legiti- mate and desirable was carved out. Comparisons between the two policies reveal that the framing of policy narratives can have a formative impact on their outcomes. The paper demonstrates how the governing quality of firmness fluctuated between different connotations and references, finally leading back to a deep-rooted tradition in Turkish governance. ince 1984 when the PKK commenced its armed struggle against the Turkish state, Turkish security policies have been framed around the SKurdish question with the PKK presented as the primary security threat to be tackled. Turkey’s Kurdish question has its roots in the founding of the republic in 1923, which saw Kurdish ethnicity assimilated with Turkishness. In accordance with the Treaty of Lausanne (1923), only three minorities were and continue to be officially recognized in Turkey: Armenians, Jews and Greeks. These three groups were granted minority status on the basis of their religion. Kurdish identity – whether national, racial or ethnic – was not recognized by the republic, resulting in decades of uprisings by the Kurds and oppressive and * Department assimilative politics by the state. -

Human Rights House Network

HUMAN RIGHTS HOUSE NETWORK Annual Report 2002 OSLO MOSCOW WARSAW SARAJEVO BERGEN ZAGREB NAIROBI MINSK ISTANBUL TIRANA Map of the Human Rights House Network OSLO WARSAW MOSCOW SARAJEVO BERGEN The Norwegian Human Helsinki Foundation Russian Research The Human Rights The Rafto Human Rights House for Human Rights Center for Human Rights House in Sarajevo Rights House Urtegata 50, 0187 Oslo, 00-028 Warsaw, 4 Louchnikov Lane, Ante Fijamenga 14b, Menneskerettighetenes Norway ul. Bracka 18m. 62, doorway 3, suite 5, 71000 Sarajevo, plass 1, [email protected] Poland 103982 Moscow, Russia Bosnia and 5007 Bergen , Norway Tel: +47 23 30 11 00 tel/fax +48 22 8281008, tel +7 095 206-0923 Herzegovina Tel: +47 55 21 09 30 Fax: +47 23 30 11 01 8286996, 8269875, fax +7 095 206-8853 tel/fax: Fax: +47 55 21 09 39 e-mail: 8269650 e-mail: [email protected] + 387 33 230 267 / e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: Website: 387 33 230 811 [email protected] [email protected] http://www.rhrcenter.org Helsinki Foundation The Bureau of Amnesty International Norwegian Helsinki Soldiers' Mothers for Human Rights of the Western Norway Committee Committee Human Rights Serb Civic Council Section Independent Union Norwegian Tibet Helsinki Committee Human Rights in Poland of Professional NORDPAS Committee Network Group Journalists International Society Young Journalists' Non-violence Coalition of NGO's Norwegian for Health and Association International in BH Afghanistan Human Rights "POLIS" "IZLAZ" Committee Helsinki Committee for Polish-Tibetan Moscow -

Press Release 2005 Rafto Prize to Chechnyan Human Rights Advocat

Press Release 2005 Rafto Prize to Chechnyan Human Rights Advocat Ms Lida Yusupova The Professor Thorolf Rafto Memorial Prize for 2005 is awarded to the Chechnyan lawyer and human rights advocate Ms Lida Yusupova, in recognition of her brave and unrelenting efforts to document human rights violations and act as a spokeswoman for the forgotten victims of the war in Chechnya. Ms Yusupova struggles to defend human dignity in a chaotic war situation and in a context where the working conditions and security of human rights advocates and journalists are increasingly compromised. This year’s Rafto Prize laureate, Ms Lida Yusupova (born on 15 September, 1961), has been Office Director in Grozny of the Russian human rights organisation Memorial. Ms Yusupova has been active in bringing forth lawsuits regarding human rights violations to Chechnyan courts. Memorial is one of very few such organisations that continue to operate in Chechnya. The incidents that Yusupova and her fellow co-workers in Memorial have documented are serious violations of international human rights and humanitarian law by Russian federal and Chechen security forces, committed without fear of legal consequences: Extrajudicial killings, enforced "disappearances" of civilians, illegal arrests and torture. The war in Chechnya has persisted for the past seven years, resulting in a degree of destruction that is almost incomprehensible. The policies of the Russian government in Chechnya have resulted in a marginalisation of the more moderate Chechnyan groups that have pursued peaceful approaches to end the suffering of the population. Instead, the consequence of Russian policies has been to strengthen the position of extreme Islamist groups that resort to acts of terror and suicide bombings. -

Should Politicians Be Prosecuted for Statements Made in the Exercise of Their Mandate?

Provisional version Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights Should politicians be prosecuted for statements made in the exercise of their mandate? Report Rapporteur: Mr Boriss Cilevičs, Latvia, Socialists, Democrats and Greens Group A. Draft resolution 1. The Assembly stresses the crucial importance, in a living democracy, of politicians being able to freely exercise their mandates. This requires a particularly high level of protection of politicians’ freedom of speech and freedom of assembly, both in parliament and when speaking to their constituents in public meetings or through the media. 2. The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR, the Convention) protects everyone’s freedom of speech, including the right to make statements that “shock or disturb” those who do not share the same opinions, as established in the case law of the European Court of Human Rights (the Court). 3. The Assembly also notes that freedom of speech is not unlimited. Hate speech condoning violence against certain persons or groups of persons on the grounds of race, origin, religion or political opinions, as well as calls for the violent overthrow of democratic institutions are not protected. Politicians even have a special responsibility, due to their high visibility, to refrain from such abuses. 4. Everyone, and in particular politicians, has the right to make proposals whose implementation would require changes of the constitution, provided the means advocated are peaceful and legal and the objectives do not run contrary to the fundamental principles of democracy and human rights. 5. This includes calls to change a centralist constitution into a federal or confederal one, or vice versa, or to change the legal status and powers of territorial (local and regional) entities, including to grant them a high degree of autonomy or even independence. -

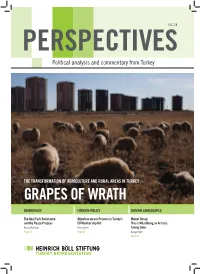

Grapes of Wrath

#6.13 PERSPECTIVES Political analysis and commentary from Turkey THE TRANSFORMATION OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL AREAS IN TURKEY GRAPES OF WRATH DEMOCRACY FOREIGN POLICY HUMAN LANDSCAPES The Gezi Park Resistance Objective versus Process in Turkey’s Memet Aksoy: and the Peace Process EU Membership Bid This is What Being an Artist is: Nazan Üstündağ Erhan İçener Taking Sides Page 54 Page 62 Ayşegül Oğuz Page 66 TURKEY REPRESENTATION Contents From the editor 3 ■ Cover story: The transformation of agriculture and rural areas in Turkey The dynamics of agricultural and rural transformation in post-1980 Turkey Murat Öztürk 4 Europe’s rural policies a la carte: The right choice for Turkey? Gökhan Günaydın 11 The liberalization of Turkish agriculture and the dissolution of small peasantry Abdullah Aysu 14 Agriculture: Strategic documents and reality Ali Ekber Yıldırım 22 Land grabbing Sibel Çaşkurlu 26 A real life “Grapes of Wrath” Metin Özuğurlu 31 ■ Ecology Save the spirit of Belgrade Forest! Ünal Akkemik 35 Child poverty in Turkey: Access to education among children of seasonal workers Ayşe Gündüz Hoşgör 38 Urban contexts of the june days Şerafettin Can Atalay 42 ■ Democracy Is the Ergenekon case a step towards democracy? Orhan Gazi Ertekin 44 Participative democracy and active citizenship Ayhan Bilgen 48 Forcing the doors of perception open Melda Onur 51 The Gezi Park Resistance and the peace process Nazan Üstündağ 54 Marching like Zapatistas Sebahat Tuncel 58 ■ Foreign Policy Objective versus process: Dichotomy in Turkey’s EU membership bid Erhan İcener 62 ■ Culture Rural life in Turkish cinema: A location for innocence Ferit Karahan 64 ■ Human Landscapes from Turkey This is what being an artist is: Taking Sides Memet Aksoy 66 ■ News from HBSD 69 Heinrich Böll Stiftung - Turkey Represantation The Heinrich Böll Stiftung, associated with the German Green Party, is a legally autonomous and intellectually open political foundation. -

Who's Who in Politics in Turkey

WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY Sarıdemir Mah. Ragıp Gümüşpala Cad. No: 10 34134 Eminönü/İstanbul Tel: (0212) 522 02 02 - Faks: (0212) 513 54 00 www.tarihvakfi.org.tr - [email protected] © Tarih Vakfı Yayınları, 2019 WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY PROJECT Project Coordinators İsmet Akça, Barış Alp Özden Editors İsmet Akça, Barış Alp Özden Authors Süreyya Algül, Aslı Aydemir, Gökhan Demir, Ali Yalçın Göymen, Erhan Keleşoğlu, Canan Özbey, Baran Alp Uncu Translation Bilge Güler Proofreading in English Mark David Wyers Book Design Aşkın Yücel Seçkin Cover Design Aşkın Yücel Seçkin Printing Yıkılmazlar Basın Yayın Prom. ve Kağıt San. Tic. Ltd. Şti. Evren Mahallesi, Gülbahar Cd. 62/C, 34212 Bağcılar/İstanbull Tel: (0212) 630 64 73 Registered Publisher: 12102 Registered Printer: 11965 First Edition: İstanbul, 2019 ISBN Who’s Who in Politics in Turkey Project has been carried out with the coordination by the History Foundation and the contribution of Heinrich Böll Foundation Turkey Representation. WHO’S WHO IN POLITICS IN TURKEY —EDITORS İSMET AKÇA - BARIŞ ALP ÖZDEN AUTHORS SÜREYYA ALGÜL - ASLI AYDEMİR - GÖKHAN DEMİR ALİ YALÇIN GÖYMEN - ERHAN KELEŞOĞLU CANAN ÖZBEY - BARAN ALP UNCU TARİH VAKFI YAYINLARI Table of Contents i Foreword 1 Abdi İpekçi 3 Abdülkadir Aksu 6 Abdullah Çatlı 8 Abdullah Gül 11 Abdullah Öcalan 14 Abdüllatif Şener 16 Adnan Menderes 19 Ahmet Altan 21 Ahmet Davutoğlu 24 Ahmet Necdet Sezer 26 Ahmet Şık 28 Ahmet Taner Kışlalı 30 Ahmet Türk 32 Akın Birdal 34 Alaattin Çakıcı 36 Ali Babacan 38 Alparslan Türkeş 41 Arzu Çerkezoğlu -

The Peace Process in Turkey-Kurdistan Has Reached a Serious Stage

0 Kongreya Neteweyî ya Kurdistanê Kurdistan National Congress Congrès National du Kurdistan KNK 1999 INFORMATION FILE 2015-03-09 THE PEACE PROCESS IN TURKEY-KURDISTAN HAS REACHED A SERIOUS STAGE HDP and AKP Government Issue joint statement: Kurdish Leader Abdullah Ocalan made a historical declaration to solve the Turkey’s question of democratization and the Kurdish Issue Will the Turkish government seize this opportunity and start the negotiations process? HEADQUARTERS. Rue Jean Stas 41 1060 Bruxelles tel: 00 32 2 647 30 84 fax: 00 32 2 647 68 49 Homepage: www.kongrakurdistan.net E-mail: [email protected] KNK UK. 6-9 Manor Gardens London N7 6LA tel: 0207 272 7890 Homepage: www.kongrakurdistan.net E-mail: [email protected] Contents I. OCALAN STATEMENT OF INTENT REGARDING A POSSIBLE PKK CONGRESS BASED ON A MINIMUM CONSENSUS ON THE 10 ARTICLES STATED ................................................... 3 II. KURDISTAN COMMUNITIES UNION KCK STATEMENTS ...................................................... 5 III. THE INTERNATIONAL REACTION AND PRESS VIEW ON THE JOINT STATEMENT ... 7 3.1 PERVIN BULDAN: MR. OCALAN‟S STATEMENT WAS HISTORIC AND AN IMPORTANT STEP FOR TURKEY ............................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 DTK: 10 ARTICLES ARE NEW OPPORTUNITY FOR SOLUTION .............................................. 8 3.3 EU STATEMENT .............................................................................................................................. -

SMITA NARULA 78 North Broadway, White Plains, New York 10603, [email protected]

SMITA NARULA 78 North Broadway, White Plains, New York 10603, [email protected] ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS ELISABETH HAUB SCHOOL OF LAW AT PACE UNIVERSITY White Plains, NY Haub Distinguished Professor of International Law Sept. 2018 - present ▪ Appointed in 2018 as the inaugural Distinguished Haub Chair in International Law to teach in the law school’s internationally renowned and top-ranked environmental law program. ▪ Courses: International Environmental Law; Environmental Justice; Human Rights & the Environment; Property Law. Committees: Appointments Committee; Admissions Committee; Nominating Committee; Environmental Law Program. Research interests: International Human Rights Law; Food Sovereignty & the Right to Food; Indigenous Peoples’ Rights; Environmental Movements; Sustainable Development Goals. Faculty Advisor: Pace International Law Review. ▪ Appointed Co-Director of the Global Center for Environmental Legal Studies in July 2019. Coordinate and supervise Haub Law students’ efforts to draft, submit, appeal and negotiate motions on international environmental law subjects for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s World Conservation Congress. HUNTER COLLEGE – CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK New York, NY Distinguished Lecturer & Interim Director 2017 – 2018 Human Rights Program, Roosevelt House Public Policy Institute ▪ Directed interdisciplinary program in human rights for undergraduate students and provided strategic direction for relevant academic, public outreach, and programming efforts. Fostered human rights -

Human R I G H Ts H O U S E Network

HUMAN RIGHTS HOUSE NETWORK Annual Report 2003 OSLO MOSCOW WARSAW SARAJEVO BERGEN ZAGREB NAIROBI MINSK ISTANBUL BAKU LONDON KAMPALA BAKU KAMPALA ISTANBUL Article 19 English PEN LONDON Index on Censorship for the the for VIASNA VIASNA Belarusian Belarusian PEN-Center Belarusian Foundation MINSK Lev Sapega Association of Journalists Law Initiative Supolnast Center Belarusian Language Language Belarusian Human Rights Center Center Rights Human F. Skaryna Partnership Partnership Skaryna F. 2 for B.a.B.e Croatian Womenís Womenís Human Rights ZAGREB Emerging Houses Croatian Law Center Law Croatian Helsinki Committee Human Rights Group and Torture Release Release Commission Legal Center NAIROBI Federation of against Women against People Against Women Lawyers Women Center for Law and Political Prisoners Political Research International Kenya Human Rights Coalition on Violence Violence on Coalition Child Rights Advisory Norwegian Committee Committee Church Aid (Norwegian AFS Norway AFS Foundation Peace Corps) Fredskorpset Idenity Project Project Idenity BERGEN War and Children and War Egil Rafto House International Exchange International Norwegian Afghanistan Norwegian of of Journalists Renesansa Professional Professional Zene Zenama Human Rights in in Rights Human Serb Civil Council Independent Union Union Independent (Women to Women) (Women SARAJEVO Helsinki Committee for for Committee Helsinki Bosnia and Herzegovina and Bosnia of of Group Convicted Convicted Foundation Psychiatric International Independent Non-violence Frontiers Group Right -

Nationalism and Syrian Refugees in Turkey

HOW DOES THE LEFT EITHER EXCLUDE OR INCLUDE? NATIONALISM AND SYRIAN REFUGEES IN TURKEY By Cemre Aydoğan Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Relations Supervisor: Dr. Erin K. Jenne Word Count: 15487 Budapest, Hungary 2019 CEU eTD Collection ABSTRACT Since the beginning of the Syrian civil war (2011), Turkey received huge number of the Syrian refugees. Expectedly, the influx of refugees caused a dissonance among the political parties of Turkey and their migration policies. In this research, I analyze why two left-wing parties might respond in an opposite manner to a refugee influx, with different levels of inclusion. Also, I demonstrate the dissonance between minority and majority party status. I trace minority party politics as inclusive for refugees. This is a rational strategy for minority parties to maximize their constituencies. On the other side, majority party politics demonstrates that ideology is not enough to interpret the migration policies of the political parties. In other words, there are other reasons to see different level of inclusion within the party politics. I refer to historical nationalism as a source of exclusion of the left for their electoral considerations. The method of analysis relies on minority party, political party, and nationalism literature. Hence, in this research, the comparison between ideologically inclusive parties, CHP and HDP, aims to show the failure of scholars who argue conflictual, destabilizing, and polarizer role of minority parties by demonstrating a certain degree of inclusion in a minority party. CEU eTD Collection i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor Erin Jenne because I discovered my passion on nationalism and ethnic politics thanks to her endless support and guidance. -

Resolution of Turkey's Kurdish Question

Focusing on the events of the latter half of 2015, the aim of this report is to problematize the reasons for the current suspension of the process Resolution of Turkey’s Kurdish Question A Process in Crisis Edel Hughes 0 | P a g e Table of Contents: 1. Introduction 2. State policy and the Kurdish question: a change in direction? 3. The General elections of 2015 and their Impact on the Solution Process 4. Regional Dynamics 5. Conclusion: A Way Forward? Introduction The approach of the AK Party government, first elected in 2002, to the Kurdish ‘question’ in Turkey has, in general, been notable for the contrast with that of its predecessors. When the then Prime Minister Erdoğan acknowledged in 2005 that Turkey had a Kurdish “problem”, one that would be “solved through democracy,” this signalled a clear shift from the militaristic language that characterised previous leaders’ handling of the issue.1 It also paved the way for a series of democratic reforms, prompted in part by Turkey’s EU accession bid, which had the effect of improving the human rights of Turkey’s Kurdish population, notably in areas such as language and cultural rights. The change in approach to the Kurdish issue under the AK Party government, it has been suggested, is partly explained by the shared experience of Islamist and Kurdish political parties under a strictly secular, unitary Turkey: “[h]istorical parallels in the State’s treatment of Islamic and Kurdish political parties in Turkey are readily apparent. Political parties with a real or perceived “Islamist” agenda have, since the formation of the State, been viewed as a threat to the secular nature of the Turkish Republic, whereas Kurdish nationalist parties, or even those challenging the traditional State security narrative in addressing the Kurdish question (such as the Communist Party), have been seen as a threat to the unitary nature of the Turkish State. -

Aung San Suu Kyi No. 6 November 2010

Burma Aung San Suu Kyi Briefing No. 6 November 2010 Updated 17 June 2011 Introduction Aung San Suu Kyi, Burma’s pro-democracy leader FACTBOX: No. 1 and Nobel Peace laureate, has come to symbolise • Leader of Burma’s democracy movement July 2010 the struggle of Burma’s people to be free. • Has spent total of 15 years and 20 days in She has spent more than 15 years in detention, detention since 1989 most of it under house arrest. The United Nations has issued legal judgements that Aung San Suu Kyi’s detention was illegal under international law • Her party, the National League for and Burmese law. Democracy, has been banned. On Saturday 13th November 2010, a week after • Daughter of Aung San, leader of Burma’s rigged elections for a powerless Parliament, she independence movement was released from her third period of house arrest. • Winner of Nobel Peace Prize The dictatorship correctly calculated that by releasing Aung San Suu Kyi they would receive so much positive publicity it would counter the negative attention on the election. No political change As experience has shown us after two previous times that Aung San Suu Kyi has been released, it is wrong to assume that her release is a portent of possible democratic change in Burma. Aung San Suu Kyi has herself said that her own release by itself does not mean significant change while thousands of political prisoners remain in jail, and the people of Burma are not free. Since her release the dictatorship has continued to detain around 2,000 political prisoners, and denies to the United Nations that it even has political prisoners.