Volume 1, Number 1, 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20200302 Vu Ce Gd Piii Cl

Office of the Controller of Examinations VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY Midnapore - 721 102 Phone: 03222: 275-441/261-144/276-554-555 Extn.: 419/418/416/451/483/500/531 ............... Ref. No: VU/CE/GD/Partll/CL/2390/2020 Dated: March 02, 2020 Provisional List of centre for B.A. /B.Sc./ B.Com: Honours (Annual Pattern) Part: ~II Examination for the year 2020 .... NEW SYLLABUS . ' SI. Name of the Examination Centre Allotment to the Examination Centre No Colleges to appear No. of candidates Honours H.,~. B.Sc. B.Com Totai 01 Bajkul Milani Mahavidyalaya PK College 792 97 .108 997 Swarnamoyee J Mahavidyalaya YS Palpara Mahavidyalaya 02 Be Ida College Bhattar College, Narayangarh Govt. College, Govt. 391 01 02 394 Gen. Degree College, Dantan 11 03 Bhattar College Belda College 343 43 05 391 04 D<!bra Thana SKS Mahavidyalaya Sabang SK Mahavidyalaya, Siddhinath 343 15 12 370 Mahavidyalaya - 05 Egra SSB College Govt. Gen. Degree College, Mohanpur Ramnagar 301 16 51 368 College 06 Garhbeta College Chandrakona V Mahavidyalaya 523 20 0 543 Gourav Guin Memorial College Paramedical College, r;>urgapur SBSS Mahavidyalaya 07 RS Mahavidyalaya, Ghatal Chaipat SPBS Mahavidyalaya 472 19 0 491 Sukumar Sengupta Mahavidyalaya 08 l·laldia Govt. College Mahishadal Raj College 393 53 45 491 11 ;' 11111111 CJ" ciating) Controller Page ... 1 (Officiating) Vidyasagar University Midnapore-721102, W .B. Downloaded from Vidyasagar University; Copyright (c) Vidyasagar University http://ecircular.vidyasagar.ac.in/DownloadEcircular.aspx?RefId=202003027692 Office of the Controller of Examinations VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY Midnapore - 721 102 Phone: 03222: 275-441/261-144/276-554-555 Extn.: 419/418/416/451/483/500/531 .................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

DBT Star College Scheme, Govt. of India Sponsored Summer School

DBT Star College Scheme, Govt. of India Sponsored Summer School on Advanced Studies on Zoology in The Perception of Current Development Organized by Department of Zoology(UG &PG) Jhargram Raj College Mission & Vision. Jhargram Raj College, being a Government institution, offers quality education programmes at UG as well as a few PG levels under Vidyasagar University and plays an important role in spreading education in the so called backward ‘junglemahal’ area. Many students of this college come from extremely poor families and under-privileged sections of the society from remote rural areas and, are often the first-generation learners. Their requirements are quite different from that of the students belonging to middle class and comparatively well-to-do urban families. To achieve what is required of it, Jhargram Raj College functions accordingly to impart good and quality education in particular and contribute towards social welfare in general. The college has received the prestigious DBT Star scheme to enhance the quality of the learning and teaching process to stimulate original thinking through ‘hands–on’ exposure to experimental work and participation in summer schools. The DBT star scheme promotes networking and strengthens ties with other institutions and laboratories. Department of Zoology, Jhargram Raj College is not an exception and provides an exposure to the students to get the benefit of different subject experts from different colleges, institutes & universities through on line lectures and demonstration of several parts of the syllabi. This will fulfill the completion of least covered part of the syllabi by experts from different academicians including JRC staffs. Course design: The entire course is divided into 6 modules of which 4 are theoretical aspect and the rest 2 will cover the practical area as follows: Duration & Class time: 10 days (14.6.21 to 24.6.21- excluding 15.06.2021), from 11 AM to 2 PM per day; may be preponed or postponed for half an hour, according to situation & availability of Subject experts. -

3 Days International Seminar Programme Schedule 2019

Three Days International Seminar on “Environmental History and Sustainability: The Black-White Journey of Sustainable Development in Reality and Education” Organized by Departments of History (UG & PG) & Geography (UG & PG) Bajkul Milani Mahavidyalaya Kismat Bajkul, Purba Medinipur-721655 In Collaboration with World History Research Academy Held on 5th -7th February, 2019 Programme Schedule Day-1: 5th February, 2019 (Tuesday) Time/ Activities/ Person/ Personalities Place/ Venue Duration Functions Frontal Corridor, 09:00 am- Registration & Dept. of - 10:30am Breakfast Geography (UG & PG), BMM Inaugural Session (10:30am – 12:30pm) Invocation Teacher & Students Lighting of lamp Dignitaries Mr. Ardhendu Maity, GB Welcome Address President, BMM & MLA- by Chief Patron Advocate, Bhagwanpur Assembly Constituency Swami 10:30 am – Mr. Rabin Chandra Mandal Vivekananda 12:00 noon Donor Member of GB, BMM , Address by Patron Seminar Hall Member of Alumni Member Association, BMM & Social Worker Dr. P.K.Dandapath, TIC & Address by Chairman, Seminar Chairman Organizing Committee Professor Dr. Kamal Uddin Address by Chief Ahamed, Vice Chancellor, Guest Sher E Bangla Agricultural University, Bangladesh Address about the Mr. G.P.Kar, Secretary, Seminar by Seminar Organizing Organizing Committee Secretary Dr. Pikash Pratim Maity, Principal, Haldia Institute of Health Sciences Mr. Pankaj Konar, BDO, Bhagwanpur-I, Purba Medinipur, West Bengal Dr. Asis Kumar De, Associate Address by Guests of Professor & Head, Honour Department of English (UG and PG), Mahishadal Raj College (NAAC Accredited ‘A’ Grade College) Dr. Anindya Kishor Bhaumik, Ex. Principal, BMM & TIC, Swarnamoyee Jogendranath Mahavidyalaya Address & Vote of Mr. Rabin Das, Convenor Thanks Tea Break (12:30 pm – 12:40pm) 1st Technical Session: 12:40pm – 1:30pm Dr. -

PHATIK GHOSH.Pdf

M I Curriculum Vitae D N Name : DR. PHATIK CHAND GHOSH Designation : Associate Professor A Department of Bengali Midnapore College (Autonomous) P Midnapore- 721101, W.B O Education Qualification : M.A, M.Phil, Ph. D. R Permanent Address : Raghunathpur(Behind Jhargram Nursing Home),Jhargram 701507. E Contact Number : +919832719349/9434481610 Email Id : [email protected] Date Of Joining : 29/03/2007(Mahisadal Raj College) C O List of research papers published : L Ashprishata : Rabindra Natake, Erina, Jhargram, 14-18, Aug 2005 Amarendra Ganaier Kabyanaty Guchha : Punarnaba, Chirantani Kolkata, 9-13, June 2006amader L Satinath Charcha Prasanga Grantha, Divaratrir Kabya, Kolkata 554-585, July-Dec 2006, 2229- 5763 E Nijaswa Shabder Vitar : Kabi Tapan Chakraborty, Sahityer Addy Jhargram, 113-117, G 2008jalpaigurir Kobita : Anchalikatar Sima Chharie, Divaratrir Kabya, Kolkata, 131-176, Jan-April 2009, 2229-5763 E Maniker Uttar Kaler Galpa : Ekti Parichoy, Divaratrir Kabya, Kolkata, 576-588, July-Dec 2009, 2229-5763 Bokul Kathar Shampa : Oithya O Adhunikatar Udvas, Ebong Mushaera, Kolkata, 104-112, Boisakh- A Asar 1417 Nakshal Andolon : Duti Upanyas : Kinnar Roy,Purba Medinipur, 269-292, Sept 2012, 2229-6344 U Nive Jaoa Jumrah, Antarjatik Pathshala, Ghatal , 43-45, Apr-Jun 2013, 2230-9594 Pratibadi Bangla Chhoto Galpa, Purbadesh Galpapatra, Asam, 105-119 , Sharad 1409 T Biswayan O Loksanskriti : Ekti Vabna, Roddur, Kgp,43-49, April 2014 Ashapurna : Satyabati Trilogy :Eisab Purusera, Patachitra, Mahishadal Raj College, 210-229, -

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION Vacancy Status (Tentative) for the Posts of Assistant Professor in Government-Aided Colleges of West Bengal (Advt

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION Vacancy Status (Tentative) for the Posts of Assistant Professor in Government-aided Colleges of West Bengal (Advt. No. 1/2018) Bengali UR OBC-A OBC-B SC ST PWD 43 13 1 30 25 6 Sl No College University UR 1 Bankura Zilla Saradamoni Mahila Mahavidyalaya 2 Khatra Adibasi Mahavidyalaya. 3 Panchmura Mahavidyalaya. BANKURA UNIVERSITY 4 Pandit Raghunath Murmu Smriti Mahavidyalaya.(1986) 5 Saltora Netaji Centenary College 6 Sonamukhi College 7 Hiralal Bhakat College 8 Kabi Joydeb Mahavidyalaya 9 Kandra Radhakanta Kundu Mahavidyalaya BURDWAN UNIVERSITY 10 Mankar College 11 Netaji Mahavidyalaya 12 New Alipore College CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY 13 Balurghat Mahila Mahavidyalaya 14 Chanchal College 15 Gangarampur College 16 Harishchandrapur College GOUR BANGA UNIVERSITY 17 Kaliyaganj College 18 Malda College 19 Malda Women's College 20 Pakuahat Degree College 21 Jangipur College 22 Krishnath College 23 Lalgola College KALYANI UNIVERSITY 24 Sewnarayan Rameswar Fatepuria College 25 Srikrishna College 26 Michael Madhusudan Memorial College KAZI NAZRUL UNIVERSITY (ASANSOL) 27 Alipurduar College 28 Falakata College 29 Ghoshpukur College NORTH BENGAL UNIVERSITY 30 Siliguri College 31 Vivekananda College, Alipurduar 32 Mahatma Gandhi College SIDHO KANHO BIRSHA UNIVERSITY 33 Panchakot Mahavidyalaya 34 Bhatter College, Dantan 35 Bhatter College, Dantan 36 Debra Thana Sahid Kshudiram Smriti Mahavidyalaya VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY 37 Hijli College 38 Mahishadal Raj College 39 Vivekananda Satavarshiki Mahavidyalaya 40 Dinabandhu -

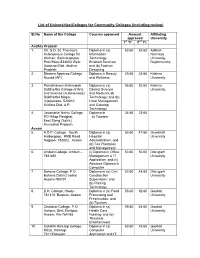

Community Colleges (Including Review)

List of Universities/Colleges for Community Colleges (including review) Sl.No Name of the College Courses approved Amount Affiliating approved University 1st Yr. 2nd Yr. Andhra Pradesh 1. Ch. S.D. St. Theresa’s Diploma in (a) 60.60 53.60 Adikavi Autonomous College for Information Nannaya Women, Sanivarapupet Technology University, Post Eluru-534003 West Enabled Services; Rajahmundry Godavari Dist. Andhra and (b) Fashion Pradesh Designing 2. Dharma Apparao College, Diploma in Beauty 25.65 23.65 Krishna Nuzvid (AP) and Wellness University 3. Parvathaneni Brahmaiah Diploma in (a) 55.60 52.60 Krishna Siddhartha College of Arts Clinical Science University and Science (Autonomous), and Medical Lab Siddhartha Nagar, Technology; and (b) Vijayawada- 520010 Hotel Management Krishna Dist, A.P. and Catering Technology 4. Jawaharlal Nehru College, Diploma in 24.65 23.65 PO Hiltop Pasighat, a) Tourism East Stang District, Arunachal Pradesh Assam 5. A.D.P. College, South Diploma in (a) 50.60 47.60 Guwahati Haiborgaon, RRB Road Hospital University Nagaon- 782002, Assam Administration; and (b) Tea Plantation and Management 6. Amburi College, Amburi – (i) Diploma in Office 60.60 50.60 Dibrugarh 785 680 Management & IT University Application; and (ii) Advance Diploma in Computer 7. Bahona College, P.O Diploma in (a) Civil 52.60 48.60 Dibrugarh Bahona District Jorhat Construction University Assam-785101 Supervision; and (b) Printing Technology 8. B.H. College, Howly- Diploma in (a) Food 55.60 52.60 Gauhati 781316, Barpeta, Assam Processing and University Preservation; and (b) Tourism 9. Chaiduar College, P.O. Diploma in (a) 55.60 46.60 Gauhati Gohpur, Dist: Sonitpur, Health Care University Assam, Pin-784165 Nursing; and (b) Theatre& Entertainment 10. -

The Seventh Eclogue of Calpurmus Siculus

I^A,US NERONIS: THE SEVENTH ECLOGUE OF CALPURMUS SICULUS Calpurnius Siculus has been served badly by posterity, being neglected to the point of near complete oblivion or, if noticed at all, dismissed con- temptuouslyl. However recently more favourable judgments of the poet's work, which see merit in both the content of Calpurnius' poetry and its technical dexterity, have been forthcoming2. While these offer a persuasive reassessment of Calpurnius' poetics, un- forrunately his supporters have felt the need to disassociate the poet from the apparent praise he showers on the emperor of the day, normally believed to have been the Emperor Nero3. Two factors seem to be at work here: one is the modern distaste for the notion of the "court" poet, the second probably a wish to distance Calpurnius from a "bad" emperor; a similar approach can be detected frequently in Virgilian criticism, where ttrere is a wish to absolve the poet from these sins4. Three recent major studies of Calpurnius, those of Leach, Davis, and Newlands, unite in seeing Calpurnius' final eclogue as indicative of the poet's doubts about Nero's ru1e5. The poem begins with Corydon being (1) E.C. J. Wight Dufl A Literary History of Rome in the Silver Age (1927) 330: "The funportance of the eclogues of T. Calpurnius Siculus rests Írs much on their testimo- ny to the continuance of one aspect of Virgil's influence as upon intrinsic poetic value". (2) E.g. R. W. Garson, The Eclogues of Calpurnius, a partial defence, "Latomus" 33, 1974,668ff.; R. Meyer, Calpurnius Siculus: technique and date, "J.R.S." 70,1980,17sff . -

MAHISHADAL RAJ COLLEGE (Govt

Serial No. – MAHISHADAL RAJ COLLEGE (Govt. Sponsored) P.O. : MAHISHADAL :: DIST : PURBA MEDINIPUR :: WEST BENGAL APPLICATION FOR ADMISSION TO THE B.A. / B.SC. / B.COM. (HONS. & GEN.) COURSE 1ST YEAR SESSION : 20………. – 20……… Course : B.A. / B.Sc. / B.Com. Honours (Subject …………………………………) / General FOR OFFICE USE Date of admission ………….……... Form issued on ……......…... PASSPORT SIZE Class ………………………….……. PHOTO TO BE PASTED HERE Roll No. ………………………….…. Signature Signature 1. a) Name in full (in Block Letters) : …………………………………………………….…...… Sex – M F b) In Bengali Scripts : ……………………………………………………………………………………....………… c) Address : Vill. : ……………….…………… P.O. : …………..…...………… P.S. : ……….………………….. Dist. : ………………………………………....….…. Contact No. (if any) : ………...………..….…………….. d) Nationality : …………………………………. Religion : ………….………………. Minority : Yes No e) Caste : Gen. S.C. S.T. O.B.C. / Sub caste : …………………..…..…… P.H. : Yes No (Attested copy of Relevant Certificate to be attached) f) Date of Birth : DAY : MONTH : YEAR : 2. a) Father’s Name : ……………………………………………………………………………………………….…… b) Mother’s Name : ………………………………………………………………………………….……………….. c) i) Guardian’s Name ……………………………………………………………...………………………………. ii) Relationship with Guardian : ………………..…………………………… iii) ……………………………….. 3. a) Particulars of H.S. / Equivalent Examination Passed : i) Examination : ………………………… ii) Roll & No. : ……….…………….….….. iii) Year : ……..….….. iv) Name of the Council / Board : ………………………………………………………………………………... v) Name of the School : ………………………………………………………………………………………….. b) Statement of marks -

Dryden's Translation of the Eclogues in a Comparative Light

Proceedings o f the Virgil Society 26 (2008) Copyright 2008 Dryden’s Translation of the Eclogues in a Comparative Light A paper given to the Virgil Society on 21 January 2006 n this paper I shall sample some passages from Dryden’s version of Virgil’s Eclogues and compare them with the renderings of other translators, both earlier and later. One of my purposes is to consider Ihow Dryden and others conceived Virgil: for example, the styles of sixteenth and seventeenth century translations of the Eclogues indicate with some clarity how the dominant idea of pastoral changed in this period. But my aim is also to study how Dryden faced the problems of translating a poet especially admired for his verbal art, partly by considering his own discussion of the matter and partly by examination of the translations themselves. Matthew Arnold declared that the heroic couplet could not adequately represent Homer; a nicer question is how well it can represent Virgil. In the ‘Discourse concerning the Original and Progress of Satire’ which he placed as a preface to his translation of Juvenal, Dryden himself declared that Virgil could have written sharper satires than either Horace or Juvenal if he had chosen to employ his talent that way.1 The lines that he took to support this contention are from the Eclogues (3.26-7): non tu in triviis, indocte, solebas, stridenti, miserum, stipula, disperdere, carmen? In the Loeb edition - by H. Rushton Fairclough, revised by G. P. Goold - the lines are rendered thus: ‘Wasn’t it you, you dunce, that at the crossroads used to murder a sorry tune on a scrannel pipe?’ ‘Scrannel’ is not part of modern vocabulary; this departure from the usual practice of the Loeb Classical Library is a matter to which I shall return. -

The West Bengal College Service Commission

THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION Vacancy Status for the Posts of Assistant Professor in Government-aided Colleges of West Bengal (Advt. No. 1/2018) The Principal/Vice-Principal/Teacher-in-Charge of the Government-aided College of West Bengal are requested to check the Vacancy status (attached herewith) for the Post of Assistant Professor in the following subject and discrepancy detected, if any, please bring it to the notice of the office of the WBCSC within 5 days. Subject SANSKRIT Date : 30/09/2019 Controller of Examinations THE WEST BENGAL COLLEGE SERVICE COMMISSION Vacancy Status for the Posts of Assistant Professor in Government-aided Colleges of West Bengal (Advt. No. 1/2018) SANSKRIT Sl No. College University UR 1 Hiralal Bhakat College BURDWAN UNIVERSITY 2 M.U.C.Women's College 3 Maharani Kasiswari College 4 Raja Peary Mohan College 5 Ramakrishna Mission Residential College 6 Sadhan Chandra Mahavidyalaya,Harindanga, Falta CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY 7 Sovarani Memorial College 8 Swami Niswambala Nanda Girls' College 9 Udaynarayanpur Madhabilata Mahavidyalaya 10 Vidyasagar College 11 Coochbehar College CPB UNIVERSITY 12 Kaliachak College GOUR BANGA UNIVERSITY 13 Chakdaha College KALYANI UNIVERSITY 14 Srikrishna College 15 Santaldih College SIDHO KANHO BIRSHA UNIVERSITY 16 Bhatter College, Dantan VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY 17 Narajole Raj College 18 Acharya Prafulla Chandra College 19 Rishi Bankim Chandra College for Women WEST BENGAL STATE UNIVERSITY 20 Saheed Nurul Islam Mahavidyalaya Sl No. College University OBC-A 1 Onda Thana Mahavidyalaya BANKURA UNIVERSITY 2 Abhedananda Mahavidyalaya 3 Kalna College BURDWAN UNIVERSITY 4 Raja Ram Mohon Roy Mahavidyalaya 5 Narasinha Dutt College 6 Ramakrishna Mission Vidyamandira CALCUTTA UNIVERSITY 7 Serampore Girls' College 8 Asansol Girls' College KAZI NAZRUL UNIVERSITY (ASANSOL) 9 Belda College 10 Mahishadal Raj College VIDYASAGAR UNIVERSITY 11 Sabang Sajanikanta Mahavidyalaya 12 Vivekananda Satavarshiki Mahavidyalaya 13 Dinabandhu Mahvidyalaya (Bongaon) WEST BENGAL STATE UNIVERSITY Sl No. -

Prospectus-2017-18.Pdf

BANDEMATARAM MAHISHADAL RAJ COLLEGE (Govt. Sponsored) , Estd. : 1946 NAAC ACCREDITED "A" GRADE COLLEGE Mahishadal : Purba Medinipur *Deen Dayal Upadhyay Kaushal Kendra. *Paschim Banga Society For Skill Development (PBSSD) Programme. *DDE Study Centre (Vidyasagar University) 2017 - ’18 PROSPECTUS Phone No. : (03224) - 240220 / 240092/241597 e-mail : College: [email protected] Principal: [email protected] Website: www.mahishadalrajcollege.com LATE KUMAR DEBAPRASAD GARGA BAHADUR (16th Nov. 1916 - 4th April. 1986) FOUNDER MAHISHADAL RAJ COLLEGE MAHISHADAL RAJ COLLEGE THE COLLEGE ahishadal Raj College is the third oldest college in the undivided district of MMidnapore and fiftieth one under University of Calcutta. The College was founded on August 1, 1946 byKumar Debaprasad Garga Bahadur , the "Raja" of Mahishadal and a celebrity in the field of music and fine arts. Now the college is affiliated to Vidyasagar University since 01.06.1985, vide letter no. 983-Edn (U) dt. 23.05.1985. Situated only twenty kilometers from both Haldia (a potential industrial town of W.B.) and Tamluk (the district headquarter of Purba Medinipur) the college has immensely benefited from its location in a pleasant, placid countryside. The college has now started its Community College Programme and Deen Dayal Upadhyaya kaushal Kendra affiliated to the MINISTRY OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT, GOVT. OF INDIAAND PASCHIM BANGA SOCIETY FOR SKILL DEVELOPMENT (PBSSD) PROGRAMME (UTKARSHA BANGLA) of the GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL and is responsibly committed to the society. 1 -

MAHISHADAL RAJ COLLEGE (Govt

MAHISHADAL RAJ COLLEGE (Govt. Sponsored), Estd - 1946 NAAC accredited ‘A’ Grade College Mahishadal , Purba Medinipur. Ref. No.: MRC/PG/19/01 Date :06.06.2019 ADMISSION NOTIFICATION FOR P.G COURSES FOR THE SESSION 2019 – 2020 Applications are invited for admission to the Post – Graduate Courses from the Students who have passed B.A / B.SC (Honours) in relevant subjects in 2018 & 2019. Those who are appearing at the Part – III / Final Examination, 2019 but the result of the said Examination has not yet been published may apply for the PG Courses. Applications are invited for admission to the following Post Graduate Courses for the academic Session 2019 - 2020. 1)Two – Year M.A Course in Bengali, English, Sanskrit & History. Eligibility : Honours in the relevant subject in 2018 & 2019 2)Two – Year M.Sc. Course in Chemistry, Applied Mathematics, Zoology & Physics. Eligibility : Honours in the relevant subject in 2018 & 2019 Read the following instructions and be sure about the eligibility for applying in different courses very carefully before submission of Online Application Form. STEP – BY – STEP PROCESS : STEP 1 : Before filling up the on-line application form, applicants have to scan their recent passport size colour photo (size 100kb ) and their signature (size 50kb) for uploading it in the form using in the CHOOSE FILE button. STEP 2 : After submitting Application form for P.G course then they have to select payment Option (on-line payment/off-line payment) for payment of the application fees, in confirmation with your application page. STEP 3 :If the candidate select offline payment of requisite Application fees, they have to take printout Copy of THREE PART BANK CHALLAN of which a) the Bank Part has to be submitted to the branch of UNITED BANK OF INDIA and deposit requisite Application Fees.(b) the College Part has to be submitted to the college office at the time of admission and (c) the Student part is for record keeping by the student.