THE RITUAL DYNAMICS of the NOTTING HILL CARNIVAL PAST and Presentl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buses from Knightsbridge

Buses from Knightsbridge 23 414 24 Buses towardsfrom Westbourne Park BusKnightsbridge Garage towards Maida Hill towards Hampstead Heath Shirland Road/Chippenham Road from stops KH, KP From 15 June 2019 route 14 will be re-routed to run from stops KB, KD, KW between Putney Heath and Russell Square. For stops Warren towards Warren Street please change at Charing Cross Street 52 Warwick Avenue Road to route 24 towards Hampstead Heath. 14 towards Willesden Bus Garage for Little Venice from stop KB, KD, KW 24 from stops KE, KF Maida Vale 23 414 Clifton Gardens Russell 24 Square Goodge towards Westbourne Park Bus Garage towards Maida Hill 74 towards Hampstead HeathStreet 19 452 Shirland Road/Chippenham Road towards fromtowards stops Kensal KH, KPRise 414From 15 June 2019 route 14from will be stops re-routed KB, KD to, KW run from stops KB, KD, KW between Putney Heath and Russell Square. For stops Finsbury Park 22 TottenhamWarren Ladbroke Grove from stops KE, KF, KJ, KM towards Warren Street please change atBaker Charing Street Cross Street 52 Warwick Avenue Road to route 24 towards Hampsteadfor Madame Heath. Tussauds from 14 stops KJ, KM Court from stops for Little Venice Road towards Willesden Bus Garage fromRegent stop Street KB, KD, KW KJ, KM Maida Vale 14 24 from stops KE, KF Edgware Road MargaretRussell Street/ Square Goodge 19 23 52 452 Clifton Gardens Oxford Circus Westbourne Bishop’s 74 Street Tottenham 19 Portobello and 452 Grove Bridge Road Paddington Oxford British Court Roadtowards Golborne Market towards Kensal Rise 414 fromGloucester stops KB, KD Place, KW Circus Museum Finsbury Park Ladbroke Grove from stops KE23, KF, KJ, KM St. -

328 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

328 bus time schedule & line map 328 Chelsea, World's End - Golders Green View In Website Mode The 328 bus line (Chelsea, World's End - Golders Green) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chelsea, World's End: 12:11 AM - 11:58 PM (2) Golders Green: 6:39 AM - 11:05 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 328 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 328 bus arriving. Direction: Chelsea, World's End 328 bus Time Schedule 48 stops Chelsea, World's End Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:11 AM - 11:58 PM Monday 12:11 AM - 11:58 PM Golders Green Station (GC) North End Road, London Tuesday 12:11 AM - 11:58 PM Dunstan Road (A) Wednesday 12:11 AM - 11:58 PM Fernside, London Thursday 12:11 AM - 11:58 PM Llanvanor Road (B) Friday 12:11 AM - 11:58 PM Childs Hill / Cricklewood Lane (D) Saturday 12:11 AM - 11:58 PM 713 Finchley Road, London Lyndale Avenue (E) Hendon Way (F) 328 bus Info A598, London Direction: Chelsea, World's End Stops: 48 Fortune Green Road (CH) Trip Duration: 69 min Line Summary: Golders Green Station (GC), Dunstan Fortune Green (CJ) Road (A), Llanvanor Road (B), Childs Hill / Rose Joan Mews, London Cricklewood Lane (D), Lyndale Avenue (E), Hendon Way (F), Fortune Green Road (CH), Fortune Green West Hampstead Police Station (CK) (CJ), West Hampstead Police Station (CK), West End Green (T), Dennington Park Road (V), West West End Green (T) Hampstead Station (W), Compayne Gardens (B), 295-297 West End Lane, London Woodchurch Road (D), Quex Road (L), Kilburn High Road / Quex Road (M), -

Ec2a 3Hr Shoreditch

SHOREDITCH EC2A 3HR A premier warehouse restoration project in the heart of With exceptional style and positioning, this is an exciting opportunity for any business. Computer generated image for illustrative purposes only. IRONWOOD WORKS EC2 A PROJECT BY AITCH 2 IRONWOOD WORKS EC2A THE BUILDING 3 Ironwood Works combines a beautiful restoration of an original warehouse building with an eye-catching full height glass and rain screen cladding two storey extension. Computer generated image for illustrative purposes only IRONWOOD WORKS EC2 A PROJECT BY AITCH 4 IRONWOOD WORKS EC2A THE BUILDING 5 The earliest records for the Ironwood Works building go back to the 1860’s, and suggest it used to be occupied by leading furniture makers. Since then, it has swapped hands between different tradesman, most notably the bell makers for St SHOREDITCH STYLE, Leonard’s Church. CRAFT AND CREATIVITY The building has managed to retain its characteristic features. The loading arches on each floor, topped by the FLOW ELEGANTLY stepped brick gable ooze with old Shoreditch charm. THROUGHOUT This building’s history and style embodies so much of what East London has been through. The style, craft and creativity IRONWOOD WORKS. of the Eastern City fringe are as much part of the fabric of this building as its bricks are. Since the 17th century Shoreditch has been an epicentre for creative trades. By the 19th century drapers, tailors, jewellers and shoe makers were all calling Shoreditch their home. These creative crafts slowly weaved an independent spirit into the fabric of Shoreditch, marking her out from mainstream London. By the late 19th century the rest of London had succumbed to the industrial revolution, yet Shoreditch rebelled against the rise of factories, and won. -

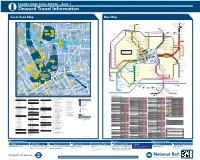

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 I Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map

London Kings Cross Station – Zone 1 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 1 35 Wellington OUTRAM PLACE 259 T 2 HAVELOCK STREET Caledonian Road & Barnsbury CAMLEY STREET 25 Square Edmonton Green S Lewis D 16 L Bus Station Games 58 E 22 Cubitt I BEMERTON STREET Regent’ F Court S EDMONTON 103 Park N 214 B R Y D O N W O Upper Edmonton Canal C Highgate Village A s E Angel Corner Plimsoll Building B for Silver Street 102 8 1 A DELHI STREET HIGHGATE White Hart Lane - King’s Cross Academy & LK Northumberland OBLIQUE 11 Highgate West Hill 476 Frank Barnes School CLAY TON CRESCENT MATILDA STREET BRIDGE P R I C E S Park M E W S for Deaf Children 1 Lewis Carroll Crouch End 214 144 Children’s Library 91 Broadway Bruce Grove 30 Parliament Hill Fields LEWIS 170 16 130 HANDYSIDE 1 114 CUBITT 232 102 GRANARY STREET SQUARE STREET COPENHAGEN STREET Royal Free Hospital COPENHAGEN STREET BOADICEA STREE YOR West 181 212 for Hampstead Heath Tottenham Western YORK WAY 265 K W St. Pancras 142 191 Hornsey Rise Town Hall Transit Shed Handyside 1 Blessed Sacrament Kentish Town T Hospital Canopy AY RC Church C O U R T Kentish HOLLOWAY Seven Sisters Town West Kentish Town 390 17 Finsbury Park Manor House Blessed Sacrament16 St. Pancras T S Hampstead East I B E N Post Ofce Archway Hospital E R G A R D Catholic Primary Barnsbury Handyside TREATY STREET Upper Holloway School Kentish Town Road Western University of Canopy 126 Estate Holloway 1 St. -

Carnival in the Creole City: Place, Race and Identity in the Age of Globalization Daphne Lamothe Smith College, [email protected]

Masthead Logo Smith ScholarWorks Africana Studies: Faculty Publications Africana Studies Spring 2012 Carnival in the Creole City: Place, Race and Identity in the Age of Globalization Daphne Lamothe Smith College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.smith.edu/afr_facpubs Part of the Africana Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lamothe, Daphne, "Carnival in the Creole City: Place, Race and Identity in the Age of Globalization" (2012). Africana Studies: Faculty Publications, Smith College, Northampton, MA. https://scholarworks.smith.edu/afr_facpubs/4 This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies: Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Smith ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected] CARNIVAL IN THE CREOLE CITY: PLACE, RACE, AND IDENTITY IN THE AGE OF GLOBALIZATION Author(s): DAPHNE LAMOTHE Source: Biography, Vol. 35, No. 2, LIFE STORIES FROM THE CREOLE CITY (spring 2012), pp. 360-374 Published by: University of Hawai'i Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23541249 Accessed: 06-03-2019 14:34 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms University of Hawai'i Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Biography This content downloaded from 131.229.64.25 on Wed, 06 Mar 2019 14:34:43 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms CARNIVAL IN THE CREOLE CITY: PLACE, RACE, AND IDENTITY IN THE AGE OF GLOBALIZATION DAPHNE LAMOTHE In both the popular and literary imaginations, carnival music, dance, and culture have come to signify a dynamic multiculturalism in the era of global ization. -

White City Ladbroke Grove North Kensington

e an L on m om C ak O ld O Site of proposed High Speed 2 rail station Saint Mary’s Catholic Cemetery O l d O a k C o m m o n L a n e Kensal Green N Cemetery M i t r e W a B y rayb roo Wormwood Scrubs k St reet W ul f Park s t a n S Me Little Wormwood t lli r tus ee St reet t Scrubs Recreation Ground B r a y b r o o k M S t e r l e Th li e e t t Fa u irway s S t r e e t H e M n F i t c i r t h e z m n W e a a a LADBROKE n y l S S t t r r e e e e t t et W re St u ald lf w st con a Er n S t ns r rde e Ga Dalgarno et rno Gardens GROVE a Dalg Barlby Road t St ree oke y St sl Wa ey ey itre sl St M et ke ree B re to t r St S a iot y Fol b r i H o H o d g a Bras e k o sie h R Ave n y nu S e c l lb v B e r h t a t r e r B m e e tre e e w R S a r d n t B al s w r t n S o o F t a e c i a Er t re ce r z d n e G w S e t a e r t M a l ll d e S R t n a r O oa r s e k l e ’ d t d s a O R 12 o a Su k B4 d nn o in C gd a W ad l m Oakworth Ro e Du u C m A an e lf R v o s o ad e t n a n n P S u L a a S c e r n n t r u g e e b e b t s o L u a r n n e e A Norbr ad o Ro v ke S Pole e tr Hammersmith h n eet ort Kensington N u Hospital e Memorial Park S t D Qu u Ca in N ne R ti orbr oad n oke S Av tree en t ue L a t H i h g Westway m i reet e l St r l C l e averswa R Latymer v oa e r R Upper School d Ba o nste a ad d E Cou ast Act rt on Lane Prim Playing Fields ula S treet Foxg S love t S E tre M et y n eet a tr h Glenroy S r A40 k Ba a n ’ m stead Du s Co C ur an R t e R R Kingsbridge Roa d o o Lane Wood ad o a H a ea th d sta d n R o ad NORTH d a o R e e r -

Download Brochure

A JEWEL IN ST JOHN’S WOOD Perfectly positioned and beautifully designed, The Compton is one of Regal London’ finest new developments. ONE BRING IT TO LIFE Download the FREE mobile Regal London App and hold over this LUXURIOUSLY image APPOINTED APARTMENTS SET IN THE GRAND AND TRANQUIL VILLAGE OF ST JOHN’S WOOD, LONDON. With one of London’s most prestigious postcodes, The Compton is an exclusive collection of apartments and penthouses, designed in collaboration with world famous interior designer Kelly Hoppen. TWO THREE BRING IT TO LIFE Download the FREE mobile Regal London App and hold over this image FOUR FIVE ST JOHN’S WOOD CULTURAL, HISTORICAL AND TRANQUIL A magnificent and serene village set in the heart of London, St John’s Wood is one of the capital’s most desirable residential locations. With an attractive high street filled with chic boutiques, charming cafés and bustling bars, there is never a reason to leave. Situated minutes from the stunning Regent’s Park and two short stops from Bond Street, St John’s Wood is impeccably located. SIX SEVEN EIGHT NINE CHARMING LOCAL EATERIES AND CAFÉS St John’s Wood boasts an array of eating and drinking establishments. From cosy English pubs, such as the celebrated Salt House, with fabulous food and ambience, to the many exceptional restaurants serving cuisine from around the world, all tastes are satisfied. TEN TWELVE THIRTEEN BREATH TAKING OPEN SPACES There are an abundance of open spaces to enjoy nearby, including the magnificent Primrose Hill, with spectacular views spanning across the city, perfect for picnics, keeping fit and long strolls. -

CARNIVAL and OTHER SEASONAL FESTIVALS in the West Indies, USA and Britain

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by SAS-SPACE CARNIVAL AND OTHER SEASONAL FESTIVALS in the West Indies, U.S.A. and Britain: a selected bibliographical index by John Cowley First published as: Bibliographies in Ethnic Relations No. 10, Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations, September 1991, University of Warwick, Coventry, CV4 7AL John Cowley has published many articles on blues and black music. He produced the Flyright- Matchbox series of LPs and is a contributor to the Blackwell Guide To Blues Records, and Black Music In Britain (both edited by Paul Oliver). He has produced two LPs of black music recorded in Britain in the 1950s, issued by New Cross Records. More recently, with Dick Spottswood, he has compiled and produced two LPs devoted to early recordings of Trinidad Carnival music, issued by Matchbox Records. His ‗West Indian Gramophone Records in Britain: 1927-1950‘ was published by the Centre for Research in Ethnic Relations. ‗Music and Migration,‘ his doctorate thesis at the University of Warwick, explores aspects of black music in the English-speaking Caribbean before the Independence of Jamaica and Trinidad. (This selected bibliographical index was compiled originally as an Appendix to the thesis.) Contents Introduction 4 Acknowledgements 7 How to use this index 8 Bibliographical index 9 Bibliography 24 Introduction The study of the place of festivals in the black diaspora to the New World has received increased attention in recent years. Investigations range from comparative studies to discussions of one particular festival at one particular location. It is generally assumed that there are links between some, if not all, of these events. -

Central London Bus and Walking Map Key Bus Routes in Central London

General A3 Leaflet v2 23/07/2015 10:49 Page 1 Transport for London Central London bus and walking map Key bus routes in central London Stoke West 139 24 C2 390 43 Hampstead to Hampstead Heath to Parliament to Archway to Newington Ways to pay 23 Hill Fields Friern 73 Westbourne Barnet Newington Kentish Green Dalston Clapton Park Abbey Road Camden Lock Pond Market Town York Way Junction The Zoo Agar Grove Caledonian Buses do not accept cash. Please use Road Mildmay Hackney 38 Camden Park Central your contactless debit or credit card Ladbroke Grove ZSL Camden Town Road SainsburyÕs LordÕs Cricket London Ground Zoo Essex Road or Oyster. Contactless is the same fare Lisson Grove Albany Street for The Zoo Mornington 274 Islington Angel as Oyster. Ladbroke Grove Sherlock London Holmes RegentÕs Park Crescent Canal Museum Museum You can top up your Oyster pay as Westbourne Grove Madame St John KingÕs TussaudÕs Street Bethnal 8 to Bow you go credit or buy Travelcards and Euston Cross SadlerÕs Wells Old Street Church 205 Telecom Theatre Green bus & tram passes at around 4,000 Marylebone Tower 14 Charles Dickens Old Ford Paddington Museum shops across London. For the locations Great Warren Street 10 Barbican Shoreditch 453 74 Baker Street and and Euston Square St Pancras Portland International 59 Centre High Street of these, please visit Gloucester Place Street Edgware Road Moorgate 11 PollockÕs 188 TheobaldÕs 23 tfl.gov.uk/ticketstopfinder Toy Museum 159 Russell Road Marble Museum Goodge Street Square For live travel updates, follow us on Arch British -

Eddie Adams Transcript

EDDIE ADAMS BRITAIN AT WORK Interviewed by Tom Vague 240 Lancaster Road North Kensington 28/5/09 Eddie Adams was a sheet metal worker on Latimer Road in the early 50s, then he worked at the Heinz factory in Harlesden, and as an electrician for the Ministry of Works and at Ford in Dagenham. As a member of the electricians’ union (ETU), he became a shop steward and the west London convenor of shop stewards at the Ministry of Works. He later worked at the Law Centre on Golborne Road and set up the Gloucester Court Reminiscence Group. Since the 50s he has also been a leading community activist in Notting Hill. Eddie has published several local history books and is still active on various community campaigns in North Kensington. Vulcan sheet metal works Latimer Road I started work at 15. My first job was at Vulcan sheet metal works which were underneath the arches in Latimer Road (now Freston Road). This was a small industrial unit which made colt cowls, which some people may remember, you can still see a few of them on chimneys. They were to draw off the smoke from the chimneys. The firm also made ventilators, and there were roughly 20 people working there. I was 15 in 1951, that’s when I started work there and I probably stayed there for two years. It was a place where lots of young people started their working life in North Kensington. One of those fairly dead end jobs but it was an introduction to work and some skills. -

Proposal to RBKC Funding Notting Hill Carnival 2019-2021

NOTTING HILL CARNIVAL Annual review 2018 A Annual 1 OVERVIEW We were honoured and proud to be appointed as Carnival organisers for 2018. We did not underestimate the challenge involved or the work required to gain the confidence and respect of carnivalists, the local community and the key strategic partners. The decision to fund us as Carnival organisers came quite late in the year and meant that we had a very tight time scale in which to engage, plan and deliver. This added additional pressure but also energised us to put pace into our work. From day one our vision was clear in that we wanted to deliver ‘A Safe, Successful and Spectacular Carnival.’ It was a vision that we promoted widely and was embraced by strategic partners and carnivalists. To achieve our vision, we set out a clear purpose: ‘to harness the energy of carnivalists and local communities to enable us to be an effective and trusted organiser of the Carnival.‘ Feedback from strategic partners, carnivalists and local residents indicates that we were successful in achieving our vision and purpose. This report is a summary of key aspects of our role as Carnival organisers. More detailed reports and documentation have been made available to our strategic partners in relation to matters such as health and safety and communications. GOVERNANCE Carnival Village Trust (the Trust) is a registered charity. It has a wholly-owned subsidiary company, TabernacleW11 Ltd, which manages the Tabernacle, Powis Square. In order to manage the particular risks associated with the Carnival, the Trust established a second subsidiary company, Notting Hill Carnival Ltd (NHC), which acted as the legal vehicle for Carnival operations. -

Cultural Placemaking in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea

Cultural Placemaking in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea Contents Introduction 4VSÁPI Inside the World’s Cultural City The Royal Borough: Seizing the Opportunity Case Studies 8LI'VIEXMZI(MWXVMGX4VSÁPIV Earl’s Court Lots Road Kensal Gasworks and Surrounds Kensington and Chelsea: Cultural Motifs Cultural Interventions: A series of initial ideas for consideration Next Steps Report Partners Introduction Councillor Nicholas Paget-Brown This publication has arisen from a desire to explore the relationship between local ambitions for arts, culture and creativity and new property developments in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Culture continues to prove its key significance to our part of London in so many ways and it is heartening that developers, artists and arts organisations have in recent times been collaborating on projects much more closely. In our desire to find the right way forward We are in an excellent position to connect for Kensington and Chelsea we wanted to developers to the creative content of the examine what has been achieved, look at borough, and thereby both to animate and emerging patterns and map out the right add value to their plans. We believe that, approach for the borough as a whole. armed with a long-term neighbourhood vision and a clear appreciation of the We are privileged to have a fabulous significance of the borough in the wider cultural mix in the borough, ranging from London context, we are in a strong internationally renowned institutions to position to broker successful partnerships creative entrepreneurs, from specialist that will benefit developers, artists, arts organisations to major creative residents, local businesses and visitors industries.