Much Ado About Zero

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6799/positional-notation-or-trigonometry-2-13-106799.webp)

Positional Notation Or Trigonometry [2, 13]

The Greatest Mathematical Discovery? David H. Bailey∗ Jonathan M. Borweiny April 24, 2011 1 Introduction Question: What mathematical discovery more than 1500 years ago: • Is one of the greatest, if not the greatest, single discovery in the field of mathematics? • Involved three subtle ideas that eluded the greatest minds of antiquity, even geniuses such as Archimedes? • Was fiercely resisted in Europe for hundreds of years after its discovery? • Even today, in historical treatments of mathematics, is often dismissed with scant mention, or else is ascribed to the wrong source? Answer: Our modern system of positional decimal notation with zero, to- gether with the basic arithmetic computational schemes, which were discov- ered in India prior to 500 CE. ∗Bailey: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA. Email: [email protected]. This work was supported by the Director, Office of Computational and Technology Research, Division of Mathematical, Information, and Computational Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy, under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231. yCentre for Computer Assisted Research Mathematics and its Applications (CARMA), University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia. Email: [email protected]. 1 2 Why? As the 19th century mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace explained: It is India that gave us the ingenious method of expressing all numbers by means of ten symbols, each symbol receiving a value of position as well as an absolute value; a profound and important idea which appears so simple to us now that we ignore its true merit. But its very sim- plicity and the great ease which it has lent to all computations put our arithmetic in the first rank of useful inventions; and we shall appre- ciate the grandeur of this achievement the more when we remember that it escaped the genius of Archimedes and Apollonius, two of the greatest men produced by antiquity. -

Zero Displacement Ternary Number System: the Most Economical Way of Representing Numbers

Revista de Ciências da Computação, Volume III, Ano III, 2008, nº3 Zero Displacement Ternary Number System: the most economical way of representing numbers Fernando Guilherme Silvano Lobo Pimentel , Bank of Portugal, Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper concerns the efficiency of number systems. Following the identification of the most economical conventional integer number system, from a solid criteria, an improvement to such system’s representation economy is proposed which combines the representation efficiency of positional number systems without 0 with the possibility of representing the number 0. A modification to base 3 without 0 makes it possible to obtain a new number system which, according to the identified optimization criteria, becomes the most economic among all integer ones. Key Words: Positional Number Systems, Efficiency, Zero Resumo Este artigo aborda a questão da eficiência de sistemas de números. Partindo da identificação da mais económica base inteira de números de acordo com um critério preestabelecido, propõe-se um melhoramento à economia de representação nessa mesma base através da combinação da eficiência de representação de sistemas de números posicionais sem o zero com a possibilidade de representar o número zero. Uma modificação à base 3 sem zero permite a obtenção de um novo sistema de números que, de acordo com o critério de optimização identificado, é o sistema de representação mais económico entre os sistemas de números inteiros. Palavras-Chave: Sistemas de Números Posicionais, Eficiência, Zero 1 Introduction Counting systems are an indispensable tool in Computing Science. For reasons that are both technological and user friendliness, the performance of information processing depends heavily on the adopted numbering system. -

Duodecimal Bulletin Vol

The Duodecimal Bulletin Bulletin Duodecimal The Vol. 4a; № 2; Year 11B6; Exercise 1. Fill in the missing numerals. You may change the others on a separate sheet of paper. 1 1 1 1 2 2 2 2 ■ Volume Volume nada 3 zero. one. two. three.trio 3 1 1 4 a ; (58.) 1 1 2 3 2 2 ■ Number Number 2 sevenito four. five. six. seven. 2 ; 1 ■ Whole Number Number Whole 2 2 1 2 3 99 3 ; (117.) eight. nine. ________.damas caballeros________. All About Our New Numbers 99;Whole Number ISSN 0046-0826 Whole Number nine dozen nine (117.) ◆ Volume four dozen ten (58.) ◆ № 2 The Dozenal Society of America is a voluntary nonprofit educational corporation, organized for the conduct of research and education of the public in the use of base twelve in calculations, mathematics, weights and measures, and other branches of pure and applied science Basic Membership dues are $18 (USD), Supporting Mem- bership dues are $36 (USD) for one calendar year. ••Contents•• Student membership is $3 (USD) per year. The page numbers appear in the format Volume·Number·Page TheDuodecimal Bulletin is an official publication of President’s Message 4a·2·03 The DOZENAL Society of America, Inc. An Error in Arithmetic · Jean Kelly 4a·2·04 5106 Hampton Avenue, Suite 205 Saint Louis, mo 63109-3115 The Opposed Principles · Reprint · Ralph Beard 4a·2·05 Officers Eugene Maxwell “Skip” Scifres · dsa № 11; 4a·2·08 Board Chair Jay Schiffman Presenting Symbology · An Editorial 4a·2·09 President Michael De Vlieger Problem Corner · Prof. -

Brahmagupta, Mathematician Par Excellence

GENERAL ARTICLE Brahmagupta, Mathematician Par Excellence C R Pranesachar Brahmagupta holds a unique position in the his- tory of Ancient Indian Mathematics. He con- tributed such elegant results to Geometry and Number Theory that today's mathematicians still marvel at their originality. His theorems leading to the calculation of the circumradius of a trian- gle and the lengths of the diagonals of a cyclic quadrilateral, construction of a rational cyclic C R Pranesachar is involved in training Indian quadrilateral and integer solutions to a single sec- teams for the International ond degree equation are certainly the hallmarks Mathematical Olympiads. of a genius. He also takes interest in solving problems for the After the Greeks' ascendancy to supremacy in mathe- American Mathematical matics (especially geometry) during the period 7th cen- Monthly and Crux tury BC to 2nd century AD, there was a sudden lull in Mathematicorum. mathematical and scienti¯c activity for the next millen- nium until the Renaissance in Europe. But mathematics and astronomy °ourished in the Asian continent partic- ularly in India and the Arab world. There was a contin- uous exchange of information between the two regions and later between Europe and the Arab world. The dec- imal representation of positive integers along with zero, a unique contribution of the Indian mind, travelled even- tually to the West, although there was some resistance and reluctance to accept it at the beginning. Brahmagupta, a most accomplished mathematician, liv- ed during this medieval period and was responsible for creating good mathematics in the form of geometrical theorems and number-theoretic results. -

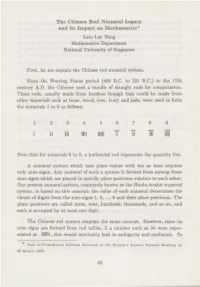

The Chinese Rod Numeral Legacy and Its Impact on Mathematics* Lam Lay Yong Mathematics Department National University of Singapore

The Chinese Rod Numeral Legacy and its Impact on Mathematics* Lam Lay Yong Mathematics Department National University of Singapore First, let me explain the Chinese rod numeral system. Since the Warring States period {480 B.C. to 221 B.C.) to the 17th century A.D. the Chinese used a bundle of straight rods for computation. These rods, usually made from bamboo though they could be made from other materials such as bone, wood, iron, ivory and jade, were used to form the numerals 1 to 9 as follows: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 II Ill Ill I IIIII T II Note that for numerals 6 to 9, a horizontal rod represents the quantity five. A numeral system which uses place values with ten as base requires only nine signs. Any numeral of such a system is formed from among these nine signs which are placed in specific place positions relative to each other. Our present numeral system, commonly known as the Hindu-Arabic numeral system, is based on this concept; the value of each numeral determines the choice of digits from the nine signs 1, 2, ... , 9 anq their place positions. The place positions are called units, tens, hundreds, thousands, and so on, and each is occupied by at most one digit. The Chinese rod system employs the same concept. However, since its nine signs are formed from rod tallies, if a number such as 34 were repre sented as Jll\IU , this would inevitably lead to ambiguity and confusion. To * Text of Presidential Address delivered at the Society's Annual General Meeting on 20 March 1987. -

Indian Mathematics

Indian Mathemtics V. S. Varadarajan University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA UCLA, March 3-5, 2008 Abstract In these two lectures I shall talk about some Indian mathe- maticians and their work. I have chosen two examples: one from the 7th century, Brahmagupta, and the other, Ra- manujan, from the 20th century. Both of these are very fascinating figures, and their histories illustrate various as- pects of mathematics in ancient and modern times. In a very real sense their works are still relevant to the mathe- matics of today. Some great ancient Indian figures of Science Varahamihira (505–587) Brahmagupta (598-670) Bhaskara II (1114–1185) The modern era Ramanujan, S (1887–1920) Raman, C. V (1888–1970) Mahalanobis, P. C (1893–1972) Harish-Chandra (1923–1983) Bhaskara represents the peak of mathematical and astro- nomical knowledge in the 12th century. He reached an un- derstanding of calculus, astronomy, the number systems, and solving equations, which were not to be achieved any- where else in the world for several centuries...(Wikipedia). Indian science languished after that, the British colonial occupation did not help, but in the 19th century there was a renaissance of arts and sciences, and Indian Science even- tually reached a level comparable to western science. BRAHMAGUPTA (598–670c) Some quotations of Brahmagupta As the sun eclipses the stars by its brilliancy, so the man of knowledge will eclipse the fame of others in assemblies of the people if he proposes algebraic problems, and still more, if he solves them. Quoted in F Cajori, A History of Mathematics A person who can, within a year, solve x2 92y2 =1, is a mathematician. -

Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania

Abstract of http://www.uog.ac.pg/glec/thesis/ch1web/ABSTRACT.htm Abstract of Counting Systems of Papua New Guinea and Oceania by Glendon A. Lean In modern technological societies we take the existence of numbers and the act of counting for granted: they occur in most everyday activities. They are regarded as being sufficiently important to warrant their occupying a substantial part of the primary school curriculum. Most of us, however, would find it difficult to answer with any authority several basic questions about number and counting. For example, how and when did numbers arise in human cultures: are they relatively recent inventions or are they an ancient feature of language? Is counting an important part of all cultures or only of some? Do all cultures count in essentially the same ways? In English, for example, we use what is known as a base 10 counting system and this is true of other European languages. Indeed our view of counting and number tends to be very much a Eurocentric one and yet the large majority the languages spoken in the world - about 4500 - are not European in nature but are the languages of the indigenous peoples of the Pacific, Africa, and the Americas. If we take these into account we obtain a quite different picture of counting systems from that of the Eurocentric view. This study, which attempts to answer these questions, is the culmination of more than twenty years on the counting systems of the indigenous and largely unwritten languages of the Pacific region and it involved extensive fieldwork as well as the consultation of published and rare unpublished sources. -

Inventing Your Own Number System

Inventing Your Own Number System Through the ages people have invented many different ways to name, write, and compute with numbers. Our current number system is based on place values corresponding to powers of ten. In principle, place values could correspond to any sequence of numbers. For example, the places could have values corre- sponding to the sequence of square numbers, triangular numbers, multiples of six, Fibonacci numbers, prime numbers, or factorials. The Roman numeral system does not use place values, but the position of numerals does matter when determining the number represented. Tally marks are a simple system, but representing large numbers requires many strokes. In our number system, symbols for digits and the positions they are located combine to represent the value of the number. It is possible to create a system where symbols stand for operations rather than values. For example, the system might always start at a default number and use symbols to stand for operations such as doubling, adding one, taking the reciprocal, dividing by ten, squaring, negating, or any other specific operations. Create your own number system. What symbols will you use for your numbers? How will your system work? Demonstrate how your system could be used to perform some of the following functions. • Count from 0 up to 100 • Compare the sizes of numbers • Add and subtract whole numbers • Multiply and divide whole numbers • Represent fractional values • Represent irrational numbers (such as π) What are some of the advantages of your system compared with other systems? What are some of the disadvantages? If you met aliens that had developed their own number system, how might their mathematics be similar to ours and how might it be different? Make a list of some math facts and procedures that you have learned. -

Number Systems and Radix Conversion

Number Systems and Radix Conversion Sanjay Rajopadhye, Colorado State University 1 Introduction These notes for CS 270 describe polynomial number systems. The material is not in the textbook, but will be required for PA1. We humans are comfortable with numbers in the decimal system where each po- sition has a weight which is a power of 10: units have a weight of 1 (100), ten’s have 10 (101), etc. Even the fractional apart after the decimal point have a weight that is a (negative) power of ten. So the number 143.25 has a value that is 1 ∗ 102 + 4 ∗ 101 + 3 ∗ 0 −1 −2 2 5 10 + 2 ∗ 10 + 5 ∗ 10 , i.e., 100 + 40 + 3 + 10 + 100 . You can think of this as a polyno- mial with coefficients 1, 4, 3, 2, and 5 (i.e., the polynomial 1x2 + 4x + 3 + 2x−1 + 5x−2+ evaluated at x = 10. There is nothing special about 10 (just that humans evolved with ten fingers). We can use any radix, r, and write a number system with digits that range from 0 to r − 1. If our radix is larger than 10, we will need to invent “new digits”. We will use the letters of the alphabet: the digit A represents 10, B is 11, K is 20, etc. 2 What is the value of a radix-r number? Mathematically, a sequence of digits (the dot to the right of d0 is called the radix point rather than the decimal point), : : : d2d1d0:d−1d−2 ::: represents a number x defined as follows X i x = dir i 2 1 0 −1 −2 = ::: + d2r + d1r + d0r + d−1r + d−2r + ::: 1 Example What is 3 in radix 3? Answer: 0.1. -

2 1 2 = 30 60 and 1

Math 153 Spring 2010 R. Schultz SOLUTIONS TO EXERCISES FROM math153exercises01.pdf As usual, \Burton" refers to the Seventh Edition of the course text by Burton (the page numbers for the Sixth Edition may be off slightly). Problems from Burton, p. 28 3. The fraction 1=6 is equal to 10=60 and therefore the sexagesimal expression is 0;10. To find the expansion for 1=9 we need to solve 1=9 = x=60. By elementary algebra this means 2 9x = 60 or x = 6 3 . Thus 6 2 1 6 40 1 x = + = + 60 3 · 60 60 60 · 60 which yields the sexagsimal expression 0; 10; 40 for 1/9. Finding the expression for 1/5 just amounts to writing this as 12/60, so the form here is 0;12. 1 1 30 To find 1=24 we again write 1=24 = x=60 and solve for x to get x = 2 2 . Now 2 = 60 and therefore we can proceed as in the second example to conclude that the sexagesimal form for 1/24 is 0;2,30. 1 One proceeds similarly for 1/40, solving 1=40 = x=60 to get x = 1 2 . Much as in the preceding discussion this yields the form 0;1,30. Finally, the same method leads to the equation 5=12 = x=60, which implies that 5/12 has the sexagesimal form 0;25. 4. We shall only rewrite these in standard base 10 fractional notation. The answers are in the back of Burton. (a) The sexagesimal number 1,23,45 is equal to 1 3600 + 23 60 + 45. -

Scalability of Algorithms for Arithmetic Operations in Radix Notation∗

Scalability of Algorithms for Arithmetic Operations in Radix Notation∗ Anatoly V. Panyukov y Department of Computational Mathematics and Informatics, South Ural State University, Chelyabinsk, Russia [email protected] Abstract We consider precise rational-fractional calculations for distributed com- puting environments with an MPI interface for the algorithmic analysis of large-scale problems sensitive to rounding errors in their software imple- mentation. We can achieve additional software efficacy through applying heterogeneous computer systems that execute, in parallel, local arithmetic operations with large numbers on several threads. Also, we investigate scalability of the algorithms for basic arithmetic operations and methods for increasing their speed. We demonstrate that increased efficacy can be achieved of software for integer arithmetic operations by applying mass parallelism in het- erogeneous computational environments. We propose a redundant radix notation for the construction of well-scaled algorithms for executing ba- sic integer arithmetic operations. Scalability of the algorithms for integer arithmetic operations in the radix notation is easily extended to rational- fractional arithmetic. Keywords: integer computer arithmetic, heterogeneous computer system, radix notation, massive parallelism AMS subject classifications: 68W10 1 Introduction Verified computations have become indispensable tools for algorithmic analysis of large scale unstable problems (see e.g., [1, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10]). Such computations require spe- cific software tools; in this connection, we mention that our library \Exact computa- tion" [11] provides appropriate instruments for implementation of such computations ∗Submitted: January 27, 2013; Revised: August 17, 2014; Accepted: November 7, 2014. yThe author was supported by the Federal special-purpose program "Scientific and scientific-pedagogical personnel of innovation Russia", project 14.B37.21.0395. -

Rationale of the Chakravala Process of Jayadeva and Bhaskara Ii

HISTORIA MATHEMATICA 2 (1975) , 167-184 RATIONALE OF THE CHAKRAVALA PROCESS OF JAYADEVA AND BHASKARA II BY CLAS-OLOF SELENIUS UNIVERSITY OF UPPSALA SUMMARIES The old Indian chakravala method for solving the Bhaskara-Pell equation or varga-prakrti x 2- Dy 2 = 1 is investigated and explained in detail. Previous mis- conceptions are corrected, for example that chakravgla, the short cut method bhavana included, corresponds to the quick-method of Fermat. The chakravala process corresponds to a half-regular best approximating algorithm of minimal length which has several deep minimization properties. The periodically appearing quantities (jyestha-mfila, kanistha-mfila, ksepaka, kuttak~ra, etc.) are correctly understood only with the new theory. Den fornindiska metoden cakravala att l~sa Bhaskara- Pell-ekvationen eller varga-prakrti x 2 - Dy 2 = 1 detaljunders~ks och f~rklaras h~r. Tidigare missuppfatt- 0 ningar r~ttas, sasom att cakravala, genv~gsmetoden bhavana inbegripen, motsvarade Fermats snabbmetod. Cakravalaprocessen motsvarar en halvregelbunden b~st- approximerande algoritm av minimal l~ngd med flera djupt liggande minimeringsegenskaper. De periodvis upptr~dande storheterna (jyestha-m~la, kanistha-mula, ksepaka, kuttakara, os~) blir forstaellga0. 0 . f~rst genom den nya teorin. Die alte indische Methode cakrav~la zur Lbsung der Bhaskara-Pell-Gleichung oder varga-prakrti x 2 - Dy 2 = 1 wird hier im einzelnen untersucht und erkl~rt. Fr~here Missverst~ndnisse werden aufgekl~rt, z.B. dass cakrav~la, einschliesslich der Richtwegmethode bhavana, der Fermat- schen Schnellmethode entspreche. Der cakravala-Prozess entspricht einem halbregelm~ssigen bestapproximierenden Algorithmus von minimaler L~nge und mit mehreren tief- liegenden Minimierungseigenschaften. Die periodisch auftretenden Quantit~ten (jyestha-mfila, kanistha-mfila, ksepaka, kuttak~ra, usw.) werden erst durch die neue Theorie verst~ndlich.