Much Bigger Than a Hamburger: Disrupting Problematic Picturebook Depictions of the Civil Rights Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Celebration of Comic Genius W.C. Fields

The Film Committee OF The National Arts Club Presents W.C. Fields Commemorative U.S. Postage Stamp Performing Arts Series, First Class, Issued January 29, 1980, W.C. Fields 100th Birthday. Ceremony at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. If I can make them laugh and through that laughter make this old world seem just a little brighter, then I am satisfied. - W.C. Fields The mission of The National Arts Club is to stimulate, foster and promote public interest in the arts and educate the American peo- A Celebration of ple in the fine arts. It was founded in 1898 by Charles de Kay, a literary and art critic for The New York Times. The Tilden Mansion at 15 Gramercy Park South, a National Historic Landmark, has been Comic Genius W.C. Fields home of The National Arts Club since 1906. www.nationalartsclub.org Wednesday, June 27, 2018 at 8:00 PM W.C. FIELDS is the “Icon of American Culture and Humor” (Librarian of Program Agenda Congress, 2000). His career spans the world’s modern entertainment heritage from the Bowery to vaudeville throughout the world on nearly every continent, Introductions back to Broadway as star on stage, silent films, talking films in Hollywood, and Gary Shapiro, Co-Chair of The National Arts Club Film Committee radio. The Timelessness of W.C. Fields’ art and humor is as relevant today as Background context – Dr. Harriet Fields before. There is no instance in the human condition that we cannot find solace in the art of W.C. Fields, for humor is the best medicine of all. -

Found, Featured, Then Forgotten: U.S. Network TV News and the Vietnam Veterans Against the War © 2011 by Mark D

Found, Featured, then Forgotten Image created by Jack Miller. Courtesy of Vietnam Veterans Against the War. Found, Featured, then Forgotten U.S. Network TV News and the Vietnam Veterans Against the War Mark D. Harmon Newfound Press THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE LIBRARIES, KNOXVILLE Found, Featured, then Forgotten: U.S. Network TV News and the Vietnam Veterans Against the War © 2011 by Mark D. Harmon Digital version at www.newfoundpress.utk.edu/pubs/harmon Newfound Press is a digital imprint of the University of Tennessee Libraries. Its publications are available for non-commercial and educational uses, such as research, teaching and private study. The author has licensed the work under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/. For all other uses, contact: Newfound Press University of Tennessee Libraries 1015 Volunteer Boulevard Knoxville, TN 37996-1000 www.newfoundpress.utk.edu ISBN-13: 978-0-9797292-8-7 ISBN-10: 0-9797292-8-9 Harmon, Mark D., (Mark Desmond), 1957- Found, featured, then forgotten : U.S. network tv news and the Vietnam Veterans Against the War / Mark D. Harmon. Knoxville, Tenn. : Newfound Press, University of Tennessee Libraries, c2011. 191 p. : digital, PDF file. Includes bibliographical references (p. [159]-191). 1. Vietnam Veterans Against the War—Press coverage—United States. 2. Vietnam War, 1961-1975—Protest movements—United States—Press coverage. 3. Television broadcasting of news—United States—History—20th century. I. Title. HE8700.76.V54 H37 2011 Book design by Jayne White Rogers Cover design by Meagan Louise Maxwell Contents Preface ..................................................................... -

Literary Journal I S M

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE IALJS Literary jourNAl i s m VOL 4 NO 2 INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR LITERARY JOURNALISM STUDIES SPRING 2010 REGISTRATION INFO LONDON IN THE of our association’s founding members, FOR ANNUAL MEETING Susan Greenberg of Roehampton University. With the generous support of IN LONDON IN MAY LATE SPRINGTIME The registration for our annual conference her university’s Centre for Research in Or, if you prefer, at the first blush of Creative and Professional Writing and in May at Roehampton University in summer...see you at IALJS-5. London can be completed on our web site with the kind assistance of the chair of our Conference Planning committee, <http://www.ialjs.org/?page_id-37> using By David Abrahamson, Northwestern (U.S.A.) your credit card and our PayPal account. Maria Lassilo-Marisalo of the University You may also register with the form on of Jyväskylä, Susan has attended to a Page 3 inside. As with past conferences, t has been weath of details to insure that the 20-22 there is a substantial discount for early said before, May meeting in London will be a memo- registration which we hope that you will but it can rable one. An interesting article about find attractive. Iperhaps bear the Centre, its history and its programs repeating: As can be found on Page 2. with almost all Given all the accommodation FUTURE SITES learned soci- options in London, we thought it best FOR CONFERENCES eties, the under- not to have an official “convention The following future IALJS convention lying purpose hotel” for this annual meeting. -

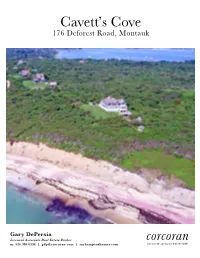

Cavett's Cove

Cavett’s Cove 176 Deforest Road, Montauk Gary DePersia Licensed Associate Real Estate Broker m: 516.380.0538 | [email protected] | myhamptonhomes.com Property Details / Amenities / Features - Traditional - Central Air Conditioning - Extensive Gardens and Mature Landscaping - 20 Acres - Whole House Generator with Auto Start - 900’ Oceanfront with Private Access - Originally Buily in 1880 and - 600 Amp Electrical Service - Private Pond Rebuilt in 2000 - Alarm System - Borders 200’ Acres of Parkland - 3 Stories - Cable/Wifi Ready - Architect: Stanford White - Cedar Shingle Exterior - Sonos Audio System - Sited by: Frederick Law Olmsted - Pine, Brick and Cherry Flooring - Well Water with Filtration - Builder: Men at Work - 7,000 SF+/- (1 Well for Home, 1 for Pool) - 6 Bedrooms - Irrigation System - 4 Bathrooms - Free Form Pool - Finished Lower Level - Pagoda Pool Lounge Area - 4 Fireplaces - Attached 2-Car Garage - Oil Hot Air Heating - Private Driveway First Floor - Living Room with Fireplace - Eat-in Kitchen with: - Luxury Appliances Includes: - Office - Breakfast Nook/Screen Porch - Bosch Refrigerator - Den with Fireplace - White Marble Counter Tops - Thermadore 5 Burner Gas Range - Formal Dining Room - Custom Cabinetry - 2 GE Stacked Wall Oven - Screened Porch - Dual Sinks with Disposals - 2 Miele Dishwashers - Wrap Around Porches - Walk-in Pantry - GE Microwave - Sub Zero Ice Maker Second Floor Third Floor - Master Bedroom Suite - 2 Full Bathrooms - Guest Bedroom - 4 Additional Guest Bedrooms - Laundry Room with Bosch System (2 with Fireplaces) Lower Level - Media Room - Storage Room - Garage Front Exterior - Laundry Center with Maytag System - Mechanical Room CAVETT’S COVE Montauk. Envision land encompassing 20 private oceanfront acres offering both sunrises and sunsets. Next, imagine a dramatic cliff with a staircase down to a private shoreline stretching 900 feet along one of the most pristine soft, sandy beaches. -

Doc Nyc Announces Awards and Record Attendance for Sixth Annual Festival

DOC NYC ANNOUNCES AWARDS AND RECORD ATTENDANCE FOR SIXTH ANNUAL FESTIVAL Motley’s Law and Class Divide Win Grand Jury Prizes Left on Purpose Wins SundanceNow Doc Club Audience Award Festival Attendance Up 21%; 200 Films and Events Plus Dozens of Special Guests, Including Secretary Hillary Rodham Clinton, In Attendance NEW YORK, Nov. 19, 2015 – On the evening of its final day of programming, DOC NYC announced its 2015 award-winners as well as news of record attendance. Now in its sixth edition, showcasing 200 films and events, the festival is the largest documentary festival in the U.S. This year’s event, which ran from November 12-19 at IFC Center, SVA Theatre and the Bow Tie Chelsea Cinemas, chalked up record-breaking ticket sales, with a 21% increase in attendance, reflecting more than 60 sold out screenings and close to 30,000 attendees. Among the 104 feature-length documentaries featured were 27 world premieres, 15 U.S. premieres and 39 New York City premieres, along with 77 short films and 35 panels and masterclasses in the newly expanded DOC NYC PRO professional development forum. Over 200 documentary makers presented their films to New York City audiences. Filmmakers in attendance included Michael Moore, Frederick Wiseman, Barbara Kopple, Jon Alpert, Ethan Hawke, Amy Berg, Kirby Dick, Alex Gibney, Kim Longinotto, Liz Garbus, Davis Guggenheim, Asif Kapadia, Brett Morgen, Morgan Neville, Stanley Nelson, and Joshua Oppenheimer. Other special guests included Secretary Hillary Rodham Clinton, Martin Scorsese, Susan Sarandon, Danny DeVito, Sharon Jones, Dick Cavett, Omar Epps, Malik Yoba, Bill Binney, Sonia Sanchez, Gilbert Gottfried, Yvonne Rainer, Elizabeth Streb, and Beau Willimon. -

Eat at the Embers & We'll Pay the Gas*

last of Lovers' still fun By Genie Campbell Of The State Journal Comedies by Neil Simon wash in on crashing waves of laughter. Only, too often the fun loses its initial potency. Simon writes for the times and he gets stale very quickly when the times leave his material behind. Yet, no matter the vintage, a Neil Simon on its mark is guaranteed to Wisconsin State Journal liven up the place as "The Last of the Red Hot Lovers" is currently doing at Wilson St. East Dinner Playhouse. Friday, Auguit 17, 1979, Section 6, Page 7 The three-act play is about Barney Cashman, a conservative, married The three acts arje broken up into Elaine knows too much. separate vignettes as our awkward, Number two is Bobbl Michele, an Theater review bumbling hero tries to score. If he's unemployed nightclub singer who not sure what he's doing, neither are lives ,wlth a Nazi vocal coach and in- the women he brings home to cessantly relates tales that makes man who decides after 23 years of mother's. Barney's hair — what he has left of it marriage to break loose just once. At The taxing male lead is well played — stand on end. Carol Rathe is cute 47 he's beginning to feel the monotony by Michael Oberfield, a Wilson St. and zany in the role. But she is a little of middle age creeping in. regular who builds the role of the too liberal for our hero, even for just "Not only has life not been very klutzy would-be lover into an explosion one afternoon. -

John R. Bolton

JOHN R. BOLTON John R. Bolton was appointed as United States Permanent Representative to the United Nations on August 1, 2005 and served until his resignation in December 2006. Prior to his appointment, Bolton served as Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security from May 2001 to May 2005. Throughout his distinguished career, Bolton has been a staunch defender of American interests. While Under Secretary, he repeatedly advocated tough measures against the nuclear weapons programs of both Iran and North Korea, and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction generally. He led negotiations for America to withdraw from the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty so that the Bush Administration could proceed with a national missile-defense program. During his tenure at the United Nations, he was a leading voice on the need for the Security Council to take strong and meaningful action against international proliferation and terrorism. Along with France’s ambassador, Bolton led the Security Council to approve a unanimous resolution to end the summer 2006 Hezbollah war on Israel, to authorize U.N. peacekeepers and to create an arms embargo against Hezbollah. He also assembled an international coalition that blocked the bid of Hugo Chavez, Venezuela's Marxist strongman, to join the Security Council. Bolton was also an advocate for human rights while serving at the UN. He arranged the Security Council's first deliberations on Burma's human rights abuses. He invited actor George Clooney and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel to brief the Security Council in September 2006 on the Khartoum regime's mass-murder of non-Arabs in Darfur, Sudan. -

The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980)

Lawrence Murray 2013-2014 J576 The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980) The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980) By Lawrence Murray 1 Lawrence Murray 2013-2014 J576 The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980) ABSTRACT The image of the broadcast news journalist is one that we can identify with on a regular basis. We see the news as an opportunity to be engaged in the world at large. Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update” brought a different take on the image of the journalist: one that was a satire on its head, but a criticism of news culture as a whole. This article looks at the first five seasons of Saturday Night Live’s “Weekend Update” and the image of the journalist portrayed by the SNL cast members serving as cast members from 1975 (Chevy Chase) until 1980 (Bill Murray and Jane Curtin). This article will show how the anchors’ style and substance does more than tell jokes about the news. The image of the journalist portrayed through the 1970s version of “Weekend Update” is mostly a negative one; while it acknowledges the importance of news and information by being a staple of the show, it ultimately mocks the news and the journalists who are prominently featured on the news. 2 Lawrence Murray 2013-2014 J576 The Fake News: Examining the Image of the Journalist Through Weekend Update (Part I: 1975-1980) INTRODUCTION: WEEKEND UPDATE Saturday Night Live is a sketch comedy show that debuted on NBC in 1975. -

The Ridgefield Encyclopedia ===

=== THE RIDGEFIELD ENCYCLOPEDIA === A compendium of nearly 4,500 people, places and things relating to Ridgefield, Connecticut. by Jack Sanders [Note: Abbreviations and sources are explained at the end of the document. This work is being constantly expanded and revised; this version was updated on 4-27-2021.] A A&P: The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company opened a small grocery store at 378 Main Street in 1948 (long after liquor store — q.v.); moved to 378 Main Street in the Bissell Building in the early 1940s. It became a supermarket at 46 Danbury Road in 1962 (now Walgreens site); closed November 1981. [JFS] [DD100] A&P Liquor Store: Opened at ONS133½ Main Street Sept. 12, 1935; [P9/12/1935] later was located at ONS86 Main Street. [1940 telephone directory] Aaron’s Court: A short, dead-end road serving 9 of 10 lots at 45 acre subdivision on the east side of Ridgebury Road by Lewis and Barry Finch, father-son, who had in 1980 proposed a corporate park here; named for Aaron Turner (q.v.), circus owner, who was born nearby. [RN] A Better Chance (ABC) is Ridgefield chapter of a national organization that sponsors talented, motivated children from inner-cities to attend RHS; students live at 32 Fairview Avenue; program began 1987 with six students. A Birdseye View: Column in Ridgefield Press for many years, written by Duncan Smith (q.v.) Abbe family: Lived on West Lane and West Mountain, 1935-36: James E. Abbe, noted photographer of celebrities, his wife, Polly Shorrock Abbe, and their three children Patience, Richard and John; the children became national celebrities when their 1936 book, Around the World in Eleven Years. -

FINAL Release DICK CAVETT's WATERGATE 07 29 14

DICK CAVETT’S WATERGATE EXPLORES PRESIDENT NIXON’S RESIGNATION Documentary Recounts the Critical Watergate Moments Through the Lens of Celebrated Talk Show Host Premieres Friday, August 8, 2014 9:00-10:00 p.m. ET on PBS ARLINGTON, VA; July 1, 2014 -- PBS and WNET today announced a new special, DICK CAVETT’S WATERGATE , an intensely personal, intimate and entertaining look back at Watergate on the 40 th anniversary of the historic resignation of President Richard Milhous Nixon, the only president to resign the office. The documentary, featuring interviews from “The Dick Cavett Show” library — many not seen since the 70s — and new interviews with Carl Bernstein The Dick Cavett Show of 8/1/73 on location from the Senate Watergate Committee hearing room in Washington, DC. Dick (Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist), John Dean Cavett (center) is flanked by Committee Vice-Chairman, Senator (former White House counsel), Timothy Naftali Howard Baker (left), and Senator Lowell Weicker (right). (Watergate historian) and Bob Woodward (Pulitzer Credit: Daphne Productions Prize-winning journalist), premieres Friday, August 8, 2014, 9:00-10:00 p.m. ET (check local listings) on PBS — exactly 40 years to the hour since President Nixon appeared on television to announce his resignation, which would officially take effect the next day, August 9, 1974. See a preview on YouTube . “PBS is uniquely positioned to take a complex aspect of our nation’s history like Watergate and tell the story in an accessible way,” said Beth Hoppe, PBS Chief Programming Executive and General Manager, General Audience Programming. “We are proud to present our viewers this enthralling real-life political drama through the unique perspective of Dick Cavett.” “As the Watergate scandal unfolded on TV and in the newspapers, it had all the ingredients of high drama — gripping and all-consuming,” said Stephen Segaller, WNET Vice President, Programming. -

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE Presents Academy Award®-Nominated Film Last Days in Vietnam in Conjunction with 40Th Anniversary of the Fall of Saigon

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE Presents Academy Award®-Nominated Film Last Days in Vietnam in Conjunction with 40th Anniversary of the Fall of Saigon Premieres Tuesday, April 28, 2015 9:00-11:00 p.m. ET on PBS April 1975. During the chaotic final days of the Vietnam War, as the North Vietnamese Army closed in on Saigon, South Vietnamese resistance crumbled. City after city and village after village fell to the North while the few U.S. diplomats and military operatives still in the country contemplated withdrawal. With the lives of thousands of South Vietnamese hanging in the balance, those in control faced an impossible choice––who would go and who would be left behind to face brutality, imprisonment, or even death. AMERICAN EXPERIENCE presents the Academy Award®-nominated film Last Days in Vietnam, directed by Rory Kennedy, on Tuesday, April 28, 2015, 9:00-11:00 p.m. ET (check local listings) on PBS. Scheduled in conjunction with the 40th anniversary of the fall of Saigon, the broadcast will contain additional footage not seen during the film’s theatrical release. In 1973, the Paris Peace Accords had forged a tenuous ceasefire and limited U.S. military involvement to the presence of approximately six thousand non-combat troops and advisors. While President Nixon promised a swift military response should the North Vietnamese violate the agreement, his abrupt departure from the White House in late 1974 left in its wake a Congress unwilling to appropriate funds to Vietnam or put U.S. soldiers back in harm’s way. By early March 1975, huge swaths of territory were overrun daily by the North Vietnamese Army, and by the end of the month, they had surrounded the capital, preparing to launch their final assault on Saigon. -

Fight 1 Reel A, 9/30/68 Reel-To-Reel 2

Subgroup VI. Audio / Visual Material Series 1. Audio Media Unboxed Reels Reel-to-Reel 1. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 1 Reel A, 9/30/68 Reel-to-Reel 2. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 1 Reel B, 9/30/68 Reel-to-Reel 3. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 2 Reel A, 10/7/68 Reel-to-Reel 4. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 2 Reel B, 10/7/68 Reel-to-Reel 5. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 3 Reel A, 10/14/68 Reel-to-Reel 6. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 3 Reel B, 10/14/68 Reel-to-Reel 7. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 4 Reel A, 10/21/68 Reel-to-Reel 8. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 4 Reel B, 10/21/68 Reel-to-Reel 9. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 5 Reel A, 10/28/68 Reel-to-Reel 10. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 5 Reel B, 10/28/68 Reel-to-Reel 11. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 6 Reel A, 11/4/68 Reel-to-Reel 12. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 6 Reel B, 11/4/68 Reel-to-Reel 13. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 7 Reel A, 11/8/68 Reel-to-Reel 14. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 7 Reel B, 11/8/68 Reel-to-Reel 15. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 8 Reel A, 11/18/68 Reel-to-Reel 16. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 8 Reel B, 11/18/68 Reel-to-Reel 17. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 9 Reel A, 11/25/68 Reel-to-Reel 18. Computer bouts, Middleweight: Fight 9 Reel B, 11/25/68 Reel-to-Reel 19.