First Step to Broken Hill by KEN MCQUEEN IAE, University of Canberra, ACT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hill Landscape Evolution of Far Western New South Wales

REGOLITH AND LANDSCAPE EVOLUTION OF FAR WESTERN NEW SOUTH WALES S.M. Hill CRC LEME, Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Adelaide, SA, 5005 INTRODUCTION linked with a period of deep weathering and an erosional and sedimentary hiatus (Idnurm and Senior, 1978), or alternatively The western New South Wales landscape contains many of the denudation and sedimentation outside of the region I areas such as elements that have been important to the study of Australian the Ceduna Depocentre (O’Sullivan et al., 1998). Sedimentary landscapes including ancient, indurated and weathered landscape basin development resumed in the Cainozoic with the formation remnants, as well as young and dynamic, erosive and sedimentary of the Lake Eyre Basin in the north (Callen et al., 1995) and the landforms. It includes a complex landscape history closely related Murray Basin in the south (Brown and Stephenson, 1991; Rogers to the weathering, sedimentation and denudation histories of et al., 1995). Mesozoic sediments in the area of the Bancannia major Mesozoic and Cainozoic sedimentary basins and their Basin (Trough) have been traditionally considered as part of the hinterlands, as well as the impacts of climate change, eustacy, Eromanga Basin, which may have been joined to the Berri Basin tectonics, and anthropogenic activities. All this has taken place through this area. Cainozoic sediments in the Bancannia Basin across a vast array of bedrock types, including regolith-dominated have been previously described within the framework of the Lake areas extremely prospective for mineral exploration. Eyre Basin (Neef et al., 1995; Gibson, this volume), but probably PHYSICAL SETTINGS warrant a separate framework. -

Rasp Mine Historic Heritage Assessment Report

FINAL REPORT Broken Hill Operations Pty Ltd Rasp Mine Heritage Impact Assessment November 2007 Environmental Resources Management Australia Building C, 33 Saunders Street Pyrmont, NSW 2009 Telephone +61 2 8584 8888 Facsimile +61 2 8584 8800 www.erm.com Approved by: Louise Doherty Position: Project Manager Signed: Date: November, 2007 Approved by: Shelley James Position: Project Director Signed: Date: November, 2007 Environmental Resources Management Australia Pty Ltd Quality System This report was prepared in accordance with the scope of services set out in the contract between Environmental Resources Management Australia Pty Ltd ABN 12 002 773 248 (ERM) and the Client. To the best of our knowledge, the proposal presented herein accurately reflects the Client’s intentions when the report was printed. However, the application of conditions of approval or impacts of unanticipated future events could modify the outcomes described in this document. In preparing the report, ERM used data, surveys, analyses, designs, plans and other information provided by the individuals and organisations referenced herein. While checks were undertaken to ensure that such materials were the correct and current versions of the materials provided, except as otherwise stated, ERM did not independently verify the accuracy or completeness of these information sources CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 1.2 SITE LOCATION 1 1.3 METHODOLOGY 1 1.4 REPORT STRUCTURE 2 1.5 AUTHORSHIP 3 2 HERITAGE CONTEXT AND STATUTORY FRAMEWORK 2.1 GENERAL OVERVIEW 7 2.2 NSW HERITAGE -

Your Complete Guide to Broken Hill and The

YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO DESTINATION BROKEN HILL Mundi Mundi Plains Broken Hill 2 City Map 4–7 Getting There and Around 8 HistoriC Lustre 10 Explore & Discover 14 Take a Walk... 20 Arts & Culture 28 Eat & Drink 36 Silverton Places to Stay 42 Shopping 48 Silverton prospects 50 Corner Country 54 The Outback & National Parks 58 Touring RoutEs 66 Regional Map 80 Broken Hill is on Australian Living Desert State Park Central Standard Time so make Line of Lode Miners Memorial sure you adjust your clocks to suit. « Have a safe and happy journey! Your feedback about this guide is encouraged. Every endeavour has been made to ensure that the details appearing in this publication are correct at the time of printing, but we can accept no responsibility for inaccuracies. Photography has been provided by Broken Hill City Council, Destination NSW, NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service, Simon Bayliss, The Nomad Company, Silverton Photography Gallery and other contributors. This visitor guide has been designed by Gang Gang Graphics and produced by Pace Advertising Pty. Ltd. ABN 44 005 361 768 Tel 03 5273 4777 W pace.com.au E [email protected] Copyright 2020 Destination Broken Hill. 1 Looking out from the Line Declared Australia’s first heritage-listed of Lode Miners Memorial city in 2015, its physical and natural charm is compelling, but you’ll soon discover what the locals have always known – that Broken Hill’s greatest asset is its people. Its isolation in a breathtakingly spectacular, rugged and harsh terrain means people who live here are resilient and have a robust sense of community – they embrace life, are self-sufficient and make things happen, but Broken Hill’s unique they’ve always got time for each other and if you’re from Welcome to out of town, it doesn’t take long to be embraced in the blend of Aboriginal and city’s characteristic old-world hospitality. -

A S H E T News

1 ASHET News July 2008 Volume 1, number 3 ASHET News July 2008 Newsletter of the Australian Society for History of Engineering and Technology ASHET member Vicki Hastrich’s novel The Great Arch, has been published by Allen & Unwin. It was Election of office bearers and committee written under the umbrella of the members University of Sydney as part of a Doctor of Arts degree and is Vicki’s second At the ASHET annual general meeting on Tuesday 22 April, all the work of fiction. The first, Swimming former office bears and committee members retired, in accordance with with the Jellyfish, was published by the provisions of he constitution, and a new committee was elected, Simon & Schuster in 2001. taking office at the end of the meeting. This committee will serve until In her talk Vicki spoke about the the next annual general meeting in 2009. difference between researching for fiction and non-fiction. The Reverend The new committee is as follows: Frank Cash, an eccentric Anglican president: Ian Jack minister who was obsessed with the senior vice-president: Mari Metzke construction of the Sydney Harbour vice president: David Craddock Bridge, was the real life model for the Vicki Hastrich secretary: Ian Arthur novel’s central character. treasurer: John Roberts In September this year, Ron Ringer’s book The Brickmasters will be committee members: Felicity Barry published by Dry Press Publishing. As an alterative history of Sydney, Glenn Rigden, The Brickmasters explores the impact Robert Renew of social, economic, technological and architectural change on one of Australia’s most historic and vital Bridges over the Cudgegong industries. -

The Railway Line to Broken Hill

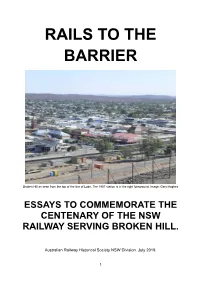

RAILS TO THE BARRIER Broken Hill as seen from the top of the line of Lode. The 1957 station is in the right foreground. Image: Gary Hughes ESSAYS TO COMMEMORATE THE CENTENARY OF THE NSW RAILWAY SERVING BROKEN HILL. Australian Railway Historical Society NSW Division. July 2019. 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................ 3 HISTORY OF BROKEN HILL......................................................................... 5 THE MINES................................................................................................ 7 PLACE NAMES........................................................................................... 9 GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE....................................................................... 12 CULTURE IN THE BUILDINGS...................................................................... 20 THE 1919 BROKEN HILL STATION............................................................... 31 MT GIPPS STATION.................................................................................... 77 MENINDEE STATION.................................................................................. 85 THE 1957 BROKEN HILL STATION................................................................ 98 SULPHIDE STREET STATION........................................................................ 125 TARRAWINGEE TRAMWAY......................................................................... 133 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................... -

Welcome to Broken Hill and the Far West Region of NSW

Welcome to Broken Hill and the far west region of NSW WELCOME Broken Hill New Residents Guide Welcome ! ! ! ! to the far west of NSW The city of Broken Hill is a relaxed and welcoming community as are the regional communities of Silverton, Wilcannia, White Cliffs, Menindee, Tibooburra & Ivanhoe. Broken Hill the hub of the far west of NSW is a thriving and dynamic regional city that is home to 19,000 people and we are pleased to welcome you. Your new city is a place, even though remote, where there are wide open spaces, perfectly blue and clear skies, amazing night skies, fantastic art community, great places to eat and socialise, fabulous sporting facilities, and the people are known as the friendliest people in the world. Broken Hill is Australia’s First Heritage City, and has high quality health, education, retail and professional services to meet all of your needs. The lifestyle is one of quality, with affordable housing, career opportunities and education and sporting facilities. We welcome you to the Silver City and regional communities of the far west region of NSW. Far West Proud is an initiative of Regional Development Australia Far West to promote the Far West of NSW as a desirable region to relocate business and families. WELCOME Broken Hill New Residents Guide Short History of Broken Hill and the far west region The history of Broken Hill is a story of trials and triumphs. The discovery of the rich line of lode in Outback New South Wales was an important event in the young history of Australia. -

Population Dynamics of Eastern Grey Kangaroos in Temperate Grasslands

Population Dynamics of Eastern Grey Kangaroos in Temperate Grasslands Don Fletcher BA Institute of Applied Ecology University of Canberra A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Applied Science at the University of Canberra 2006 ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply appreciative of the support and guidance of my principal supervisor Prof. Jim Hone, throughout the project. His commitment to principles of scientific method in applied ecology, his knowledge of the literature, the breadth of his interests, and his patience, were inspiring. I also thank Stephen Sarre, my second supervisor, for his successful effort to complement what Jim provided, for constructive and friendly advice and criticism and for broadening my knowledge of the application of molecular biology to ecology. My employer, Environment ACT, supported the project in various ways throughout, especially in tolerating my absence from the office when I was undertaking fieldwork or working at the University of Canberra. I particularly thank the manager of the research group at Environment ACT, Dr David Shorthouse, for dedicated and patient support, and for ably defending the project at the necessary times, and my colleague Murray Evans who carried an extra workload in 2002–03 in my absence. I also thank the former manager of the ACT Parks and Conservation Service, Tony Corrigan, for enlisting support at a crucial time when the project was commencing. The former Marsupial CRC, particularly its leader, John Rodger, supported the project handsomely with a cash grant without which it would not have commenced. I want to thank the Applied Ecology Research Group (now the Institute of Applied Ecology) for friendly support. -

Swansea Heads Petrified Forest 9

‘Geo-Log’ 2010 Journal of the Amateur Geological Society of the Hunter Valley ‘Geo-Log’ 2010 Journal of the Amateur Geological Society of the Hunter Valley Inc. Contents: President’s Introduction 2 Putty Beach 3 Redhead Point 5 Swansea Heads Petrified Forest 9 Box Head Walk 12 Sandbar Weekend 13 Fort Scratchley Tour 15 Woy Woy Peninsular 16 ‚How the Earth Works,‛ a lecture 20 Sand Hollow, Merriwa and Bylong Excursion 25 Bateau Bay Walk 31 Social Activities 32 Broken Hill - Geological Safari 2010 34 1 Geo-Log 2010 President’s Introduction. Hello members and friends, Yet another successful year packed with interest has gone by so quickly. Our outings have continued to attract much interest and after 30 years we still manage to run new activities, while sometimes retread- ing old ground for the benefit of new members. Outings continue to provide a mix of experiences due to the varied expertise among our membership, most of who have now retired from full-time employment. Our Society is perhaps unique in that every member contributes regardless of their level of knowledge and it is this group effort and resulting ca- maraderie that makes our Society so enjoyable and successful. The extended Broken Hill trip was a re- sounding success and repaid the efforts of the organisers many times over. It was a trip that should have been run by our Society years ago, but the logistics and expertise involved with such a large and geologically complex area always seemed just too daunting. It was only with the help of staff of the DPI (Maitland Office), the people of the pastoral stations (especially Kym and John Cramp of Mount Gipps), and some of the locals (especially Trevor Dart of the Broken Hill Mineral Club) that this trip could even get off the ground. -

Processes Explaining Exotic Plant Occurrence in Australian Mountain Systems

PROCESSES EXPLAINING EXOTIC PLANT OCCURRENCE IN AUSTRALIAN MOUNTAIN SYSTEMS by Mellesa Schroder B.App.Sc. Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy School of Environmental Science Charles Sturt University Albury February 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Figures .............................................................................................................................................. v Tables .............................................................................................................................................. vii Certificate of Authorship ................................................................................................................. ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... x ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................................ xi Chapter 1 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 1.1 General introduction......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Definition of an exotic plant species ................................................................................. 2 1.3 Definition of elevation versus altitude ............................................................................. 3 1.4 Definition of disturbed -

Pest Management Strategy 2008-2011

Northern Rivers Region Pest Management Strategy 2008-2011 © Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW, 2007. You may copy, distribute, display, download and otherwise freely deal with this work for any purpose, provided that you attribute the Department as the owner. However, you must obtain permission if you wish to (1) charge others for access to the work (other than at cost), (2) include the work in advertising or a product for sale or (3) modify the work. Published by: Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW 59–61 Goulburn Street PO Box A290 Sydney South 1232 Ph: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Ph: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Ph: 1300 361 967 (national parks information and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au DECC 2008/12 ISBN 978 1 74122 695 9 www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au For further information contact: Regional Operations Coordinator Northern Rivers Region Northern Branch Parks and Wildlife Group Department of Environment and Climate Change 75 Main St PO Box 856 Alstonville NSW 2477 Telephone: (02) 66270 200 Cover photo: pandanus image Richard Gates; pied oystercatcher Simon Walsh; cane toad John Pumpurs; coastline showing bitou bush Lisa Wellman This plan should be cited as follows: Department of Environment and Climate Change NSW. (2007). Northern Rivers Region Pest Management Strategy 2008-2011. DECC, Sydney, NSW The New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) is now part of the Department of Environment and Climate Change (DECC). Throughout this strategy, references to “NPWS” should be taken to mean the NPWS carrying out functions on behalf of the Director General and the Minister of DECC. -

Aboriginal and Non Indigenous Heritage

Silverton Wind Farm NSW Stage 1 Aboriginal Heritage and Non Indigenous Heritage Assessment Volume 1 January 2008 A report to nghenvironmental on behalf of Silverton Wind Farm Developments Julie Dibden New South Wales Archaeology Pty Limited PO Box 2135 Central Tilba NSW 2546 Ph/fax 02 44737947 mob. 0427074901 [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY......................................................................................................................................................4 1.1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................................4 1.2 PARTNERSHIP WITH THE ABORIGINAL COMMUNITY.....................................................................................4 1.3 DESCRIPTION OF IMPACT..............................................................................................................................4 1.4 OBJECTIVES AND METHODS .........................................................................................................................5 1.5 PREVIOUS HERITAGE LISTINGS ....................................................................................................................6 1.6 RESULTS.......................................................................................................................................................6 1.7 CONCLUSIONS ..............................................................................................................................................7 -

STRATEGIC TOURISM PLAN 2010 to 2020 the Line of Lode CONTENTS

BROKEN HILL STRATEGIC TOURISM PLAN 2010 TO 2020 The Line of Lode CONTENTS 1 ACRONYMS 26 DESTINATION MARKETING: 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8, Brand & image 9, Strategic & tactical marketing 3 KEY DIRECTIONS 10, Visitor markets 4 COUNCIL’S ROLE IN TOURISM 11, Conferences & events 5 PLANNING APPROACH 34 IMPLEMENTATION & MONITORING 6 CONSULTATION PROCESS 35 APPENDIX 1: 7 TOURISM VISION & VALUES Objectives & membership – BHTAG 8 DESTINATION MANAGEMENT: 36 APPENDIX 2: 1, Governance Stakeholder engagement 2, Visitor information service 37 APPENDIX 3: 3, Destination research Planning principles 4, Service quality 38 APPENDIX 4: 17 DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT: Accommodation audit 5, Tourism asset management 39 APPENDIX 5: 6, Tourism product & experience Visitation to Outback NSW 7, Transport & access 40 REFERENCES DECEMBER, 2010 Prepared For Broken Hill City Council By: Dr Meredith Wray School Of Tourism & Hospitality Management Southern Cross University Living Desert Sculptures ACRONYMS BH Broken Hill NPWS National Parks and Wildlife Service BHCC Broken Hill City Council ORTO Outback Regional Tourism Organisation BHRTA Broken Hill Regional Tourism Association RDA Regional Development Australia (Far West) BHTAG Broken Hill Tourism Advisory Group SCU Southern Cross University BHVIC Broken Hill Visitor Information Centre STCRC Sustainable Tourism Cooperative Research Centre BBH Business Broken Hill (Chamber of Commerce) TA Tourism Australia DSRD Department of State and Regional Development TNSW Tourism New South Wales DKA Desert Knowledge Australia TRA Tourism