Boolcoomatta Reserve CLICK WENT the SHEARS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019 Journal of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. In this issue: Variation in songs of the White-eared Honeyeater Phenotypic diversity in the Copperback Quailthrush and a third subspecies Neonicotinoid insecticides Bird Report, 2011-2015: Part 1, Non-passerines President: John Gitsham The South Australian Vice-Presidents: Ornithological John Hatch, Jeff Groves Association Inc. Secretary: Kate Buckley (Birds SA) Treasurer: John Spiers FOUNDED 1899 Journal Editor: Merilyn Browne Birds SA is the trading name of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. Editorial Board: Merilyn Browne, Graham Carpenter, John Hatch The principal aims of the Association are to promote the study and conservation of Australian birds, to disseminate the results Manuscripts to: of research into all aspects of bird life, and [email protected] to encourage bird watching as a leisure activity. SAOA subscriptions (e-publications only): Single member $45 The South Australian Ornithologist is supplied to Family $55 all members and subscribers, and is published Student member twice a year. In addition, a quarterly Newsletter (full time Student) $10 reports on the activities of the Association, Add $20 to each subscription for printed announces its programs and includes items of copies of the Journal and The Birder (Birds SA general interest. newsletter) Journal only: Meetings are held at 7.45 pm on the last Australia $35 Friday of each month (except December when Overseas AU$35 there is no meeting) in the Charles Hawker Conference Centre, Waite Road, Urrbrae (near SAOA Memberships: the Hartley Road roundabout). Meetings SAOA c/o South Australian Museum, feature presentations on topics of ornithological North Terrace, Adelaide interest. -

Rasp Mine Historic Heritage Assessment Report

FINAL REPORT Broken Hill Operations Pty Ltd Rasp Mine Heritage Impact Assessment November 2007 Environmental Resources Management Australia Building C, 33 Saunders Street Pyrmont, NSW 2009 Telephone +61 2 8584 8888 Facsimile +61 2 8584 8800 www.erm.com Approved by: Louise Doherty Position: Project Manager Signed: Date: November, 2007 Approved by: Shelley James Position: Project Director Signed: Date: November, 2007 Environmental Resources Management Australia Pty Ltd Quality System This report was prepared in accordance with the scope of services set out in the contract between Environmental Resources Management Australia Pty Ltd ABN 12 002 773 248 (ERM) and the Client. To the best of our knowledge, the proposal presented herein accurately reflects the Client’s intentions when the report was printed. However, the application of conditions of approval or impacts of unanticipated future events could modify the outcomes described in this document. In preparing the report, ERM used data, surveys, analyses, designs, plans and other information provided by the individuals and organisations referenced herein. While checks were undertaken to ensure that such materials were the correct and current versions of the materials provided, except as otherwise stated, ERM did not independently verify the accuracy or completeness of these information sources CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 1.2 SITE LOCATION 1 1.3 METHODOLOGY 1 1.4 REPORT STRUCTURE 2 1.5 AUTHORSHIP 3 2 HERITAGE CONTEXT AND STATUTORY FRAMEWORK 2.1 GENERAL OVERVIEW 7 2.2 NSW HERITAGE -

STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS PLAN 2021-2030 Ii CITY of PORT LINCOLN – Strategic Directions Plan CONTENTS

CITY OF PORT LINCOLN STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS PLAN 2021-2030 ii CITY OF PORT LINCOLN – Strategic Directions Plan CONTENTS 1 FOREWORD 2 CITY PROFILE 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY 5 COMMUNITY ASPIRATIONS 6 VISION, MISSION and VALUES 8 GOAL 1. ECONOMIC GROWTH AND OPPORTUNITY 10 GOAL 2. LIVEABLE AND ACTIVE COMMUNITIES 12 GOAL 3. GOVERNANCE AND LEADERSHIP 14 GOAL 4. SUSTAINABLE ENVIRONMENT 16 GOAL 5. COMMUNITY ASSETS AND PLACEMAKING 18 MEASURING OUR SUCCESS 20 PLANNING FRAMEWORK 21 COUNCIL PLANS Prepared by City of Port Lincoln Adopted by Council 14 December 2020 RM: FINAL2020 18.80.1.1 City of Port Lincoln images taken by Robert Lang Photography FOREWORD On behalf of the City of Port Lincoln I am pleased to present the City's Strategic Directions Plan 2021-2030 which embodies the future aspirations of our City. This Plan focuses on and shares the vision and aspirations for the future of the City of Port Lincoln. The Plan outlines how, over the next ten years, we will work towards achieving the best possible outcomes for the City, community and our stakeholders. Through strong leadership and good governance the Council will maintain a focus on achieving the Vision and Goals identified in this Plan. The Plan defines opportunities for involvement of the Port Lincoln community, whether young or old, business people, community groups and stakeholders. Our Strategic Plan acknowledges the natural beauty of our environment and recognises the importance of our natural resources, not only for our community well-being and identity, but also the economic benefits derived through our clean and green qualities. -

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory Cant Ranch Historic District John Day Fossil Beds National Monument 2009

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2009 Cant Ranch Historic District John Day Fossil Beds National Monument ____________________________________________________ Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary and Site Plan Inventory Unit Description ................................................................................................................ 2 Site Plans ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Park Information ............................................................................................................................... 5 Concurrence Status Inventory Status ............................................................................................................................... 6 Geographic Information and Location Map Inventory Unit Boundary Description ............................................................................................... 6 State and County ............................................................................................................................. 7 Size .................................................................................................................................................. 7 Boundary UTMS ............................................................................................................................... 8 Location Map ................................................................................................................................. -

Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks Part of the Far North & Far West Region (Region 13) Historical Research Pty Ltd Adelaide in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd Lyn Leader-Elliott Iris Iwanicki December 2002 Frontispiece Woolshed, Cordillo Downs Station (SHP:009) The Birdsville & Strzelecki Tracks Heritage Survey was financed by the South Australian Government (through the State Heritage Fund) and the Commonwealth of Australia (through the Australian Heritage Commission). It was carried out by heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd, in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd, Lyn Leader-Elliott and Iris Iwanicki between April 2001 and December 2002. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia and they do not accept responsibility for any advice or information in relation to this material. All recommendations are the opinions of the heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd (or their subconsultants) and may not necessarily be acted upon by the State Heritage Authority or the Australian Heritage Commission. Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes including for personal or educational uses. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires written permission from the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to either the Manager, Heritage Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001, or email [email protected], or the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601, or email [email protected]. -

Released Under Foi

File 2018/15258/01 – Document 001 Applicant Name Applicant Type Summary All briefing minutes prepared for Ministers (and ministerial staff), the Premier (and staff) and/or Deputy Premier (and staff) in respect of the Riverbank precinct for the period 2010 to Vickie Chapman MP MP present Total patronage at Millswood Station, and Wayville Station (individually) for each day from 1 Corey Wingard MP October 30 November inclusive Copies of all documents held by DPTI regarding the proposal to shift a government agency to Steven Marshall MP Port Adelaide created from 2013 to present The total annual funding spent on the Recreation and Sport Traineeship Incentive Program Tim Whetstone MP and the number of students and employers utilising this program since its inception A copy of all reports or modelling for the establishment of an indoor multi‐sports facility in Tim Whetstone MP South Australia All traffic count and maintenance reports for timber hulled ferries along the River Murray in Tim Whetstone MP South Australia from 1 January 2011 to 1 June 2015 Corey Wingard MP Vision of rail car colliding with the catenary and the previous pass on the down track Rob Brokenshire MLC MP Speed limit on SE freeway during a time frame in September 2014 Request a copy of the final report/independent planning assessment undertaken into the Hills Face Zone. I believe the former Planning Minister, the Hon Paul Holloway MLC commissioned Steven Griffiths MP MP the report in 2010 All submissions and correspondence, from the 2013/14 and 2014/15 financial years -

Chapter 18 Non-Aboriginal Cultural Heritage

NON-ABORIGINAL CULTURAL HERITAGE 18 18.1 InTRODUCTION During the 1880s, the South Australian Government assisted the pastoral industry by drilling chains of artesian water wells Non-Aboriginal contact with the region of the EIS Study Area along stock routes. These included wells at Clayton (on the began in 1802, when Matthew Flinders sailed up Spencer Gulf, Birdsville Track) and Montecollina (on the Strzelecki Track). naming Point Lowly and other areas along the shore. Inland The government also established a camel breeding station at exploration began in the early 1800s, with the primary Muloorina near Lake Eyre in 1900, which provided camels for objective of finding good sheep-grazing land for wool police and survey expeditions until 1929. production. The region’s non-Aboriginal history for the next 100 years was driven by the struggle between the economic Pernatty Station was established in 1868 and was stocked with urge to produce wool and the limitations imposed by the arid sheep in 1871. Other stations followed, including Andamooka environment. This resulted in boom/crash cycles associated in 1872 and Arcoona and Chances Swamp (which later became with periods of good rains or drought. Roxby Downs) in 1877 (see Chapter 9, Land Use, Figures 9.3 18 and 9.4 for location of pastoral stations). A government water Early exploration of the Far North by Edward John Eyre and reserve for travelling stock was also established further south Charles Sturt in the 1840s coincided with a drought cycle, in 1882 at a series of waterholes called Phillips Ponds, near and led to discouraging reports of the region, typified by what would later be the site of Woomera. -

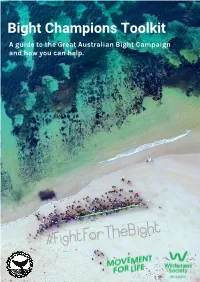

Bight Champions Toolkit a Guide to the Great Australian Bight Campaign and How You Can Help

Bight Champions Toolkit A guide to the Great Australian Bight Campaign and how you can help. Contents Great Australian Bight Campaign in a nutshell 2 Our Vision 2 Who is the Great Australian Bight Alliance? 3 Bight Campaign Background 4 A Special Place 5 The Risks 6 Independent oil spill modelling 6 Quick Campaign Snapshot 7 What do we want? 8 What you can do 9 Get the word out there 10 How to be heard 11 Writing it down 12 Comments on articles 13 Key Messages 14 Media Archives 15 Screen a film 16 Host a meet-up 18 Setting up a group 19 Contacting Politicians 20 Become a leader 22 Get in contact 23 1 Bight campaign in a nutshell THE PLACE, THE RISKS AND HOW WE SAVE IT “ The Great Australian Bight is a body of coast Our vision for the Great and water that stretches across much of Australian Bight is for a southern Australia. It’s an incredible place, teaming with wildlife, remote and unspoiled protected marine wilderness areas, as well as being home to vibrant and thriving coastal communities. environment, where marine The Bight has been home to many groups of life is safe and healthy. Our Aboriginal People for tens of thousands of years. The region holds special cultural unspoiled waters must be significance, as well as important resources to maintain culture. The cliffs of the Nullarbor are valued and celebrated. Oil home to the Mirning People, who have a special spills are irreversible. We connection with the whales, including Jidarah/Jeedara, the white whale and creation cannot accept the risk of ancestor. -

Place Names of South Australia: W

W Some of our names have apparently been given to the places by drunken bushmen andfrom our scrupulosity in interfering with the liberty of the subject, an inflection of no light character has to be borne by those who come after them. SheaoakLog ispassable... as it has an interesting historical association connectedwith it. But what shall we say for Skillogolee Creek? Are we ever to be reminded of thin gruel days at Dotheboy’s Hall or the parish poor house. (Register, 7 October 1861, page 3c) Wabricoola - A property North -East of Black Rock; see pastoral lease no. 1634. Waddikee - A town, 32 km South-West of Kimba, proclaimed on 14 July 1927, took its name from the adjacent well and rock called wadiki where J.C. Darke was killed by Aborigines on 24 October 1844. Waddikee School opened in 1942 and closed in 1945. Aboriginal for ‘wattle’. ( See Darke Peak, Pugatharri & Koongawa, Hundred of) Waddington Bluff - On section 98, Hundred of Waroonee, probably recalls James Waddington, described as an ‘overseer of Waukaringa’. Wadella - A school near Tumby Bay in the Hundred of Hutchison opened on 1 July 1914 by Jessie Ormiston; it closed in 1926. Wadjalawi - A tea tree swamp in the Hundred of Coonarie, west of Point Davenport; an Aboriginal word meaning ‘bull ant water’. Wadmore - G.W. Goyder named Wadmore Hill, near Lyndhurst, after George Wadmore, a survey employee who was born in Plymouth, England, arrived in the John Woodall in 1849 and died at Woodside on 7 August 1918. W.R. Wadmore, Mayor of Campbelltown, was honoured in 1972 when his name was given to Wadmore Park in Maryvale Road, Campbelltown. -

Steamtown Heritage Rail Centre Peterborough

ENGINEERING HERITAGE RECOGNITION STEAMTOWN HERITAGE RAIL CENTRE PETERBOROUGH Engineering Heritage SA August 2017 Cover photograph: T Class Locomotive 199 was built by James Martin & Co of Gawler and entered service on 4 March 1912 It was taken out of service in 1970; displayed in a public park from 1973 to 1980; then stored in the roundhouse until 2008 when it was given a “cosmetic restoration” and placed on display in the former diesel depot [Photo: Richard Venus 4244] Table of Contents 1. Nomination for Engineering Heritage Recognition 1 2. Agreement of Owner 2 3. Description of Work 3 4. Assessment of Significance 5 5. Petersburg: Narrow Gauge Junction (1880-1919) 6 5.1 The “Yongala” Junction 6 5.2 Petersburg-Silverton 10 5.3 Silverton Tramway Company 14 5.4 Northern Division, South Australian Railways 16 5.5 Workshop Facilities 17 5.6 Crossing the Tracks 18 5.7 New Lines and the Break of Gauge 20 6. Peterborough: Divisional Headquarters (1918-1976) 23 6.1 Railway Roundhouse 23 6.2 The Coal Gantry 24 6.3 Rail Standardisation 29 7. Steamtown Heritage Rail Centre (1977- ) 31 7.1 Railway Preservation Society, 1977-2005 31 7.2 Steamtown Heritage Rail Centre (2005- ) 33 7.3 The Sound and Light Show 34 8. Associations 37 8.1 Railway Commissioners 37 8.2 Railway Contractors 38 9. Interpretation Plan 41 9.1 Interpretation 41 9.2 Marker Placement and Presentation Ceremony 41 Appendices A1. Presentation Ceremony 42 A1.1 Presentation of Marker 42 A1.2 Significance to Peterborough 46 A2. Steamtown Structures 47 A3. -

Your Complete Guide to Broken Hill and The

YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO DESTINATION BROKEN HILL Mundi Mundi Plains Broken Hill 2 City Map 4–7 Getting There and Around 8 HistoriC Lustre 10 Explore & Discover 14 Take a Walk... 20 Arts & Culture 28 Eat & Drink 36 Silverton Places to Stay 42 Shopping 48 Silverton prospects 50 Corner Country 54 The Outback & National Parks 58 Touring RoutEs 66 Regional Map 80 Broken Hill is on Australian Living Desert State Park Central Standard Time so make Line of Lode Miners Memorial sure you adjust your clocks to suit. « Have a safe and happy journey! Your feedback about this guide is encouraged. Every endeavour has been made to ensure that the details appearing in this publication are correct at the time of printing, but we can accept no responsibility for inaccuracies. Photography has been provided by Broken Hill City Council, Destination NSW, NSW National Parks & Wildlife Service, Simon Bayliss, The Nomad Company, Silverton Photography Gallery and other contributors. This visitor guide has been designed by Gang Gang Graphics and produced by Pace Advertising Pty. Ltd. ABN 44 005 361 768 Tel 03 5273 4777 W pace.com.au E [email protected] Copyright 2020 Destination Broken Hill. 1 Looking out from the Line Declared Australia’s first heritage-listed of Lode Miners Memorial city in 2015, its physical and natural charm is compelling, but you’ll soon discover what the locals have always known – that Broken Hill’s greatest asset is its people. Its isolation in a breathtakingly spectacular, rugged and harsh terrain means people who live here are resilient and have a robust sense of community – they embrace life, are self-sufficient and make things happen, but Broken Hill’s unique they’ve always got time for each other and if you’re from Welcome to out of town, it doesn’t take long to be embraced in the blend of Aboriginal and city’s characteristic old-world hospitality. -

A Social History of Thebarton

A Social History of Thebarton Copyright – Haydon R Manning All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Haydon Manning This manuscript was never published by my father or subject to editorial review. Contents Chapter 1 The Aborigines of the Adelaide Plains 2 Colonel William Light - Surveyor of Adelaide 3 Colonel William Light - His Final Days 4 The Village of Thebarton 5 Housing, Domestic Life and Leisure Activities 6 Sources for Water Supply 7 Industries - A WorKplace for the Labour Force of Thebarton 8 Industrial Relations in Respect of the Thebarton WorK Force; Destitution, Charity and Unemployment - 1837-1900 9 Sport 10 Transport and Public Utilities 11 Education 12 Local Government and Civic Affairs 13 Religion 14 A Day in the Life of Thebarton - 1907 15 The Public Health of Thebarton 16 The Role of Women in the Community Appendix A - Information on the 344 Allotments in Thebarton Subdivided by Colonel William Light and Maria Gandy Appendix B - Nomenclature of Streets Appendix C – Information on Town ClerKs and Mayors Thebarton’s First Occupants - The Kaurna People - Contributed by Tom Gara (hereunder) 1 Chapter 1 The Aborigines of the Adelaide Plains Shame upon us! We take their land and drive away their food by what we call civilisation and then deny them shelter from a storm... What comes of all the hypocrisy of our wishes to better their condition?... The police drive them into the bush to murder shepherds, and then we cry out for more police..