The National Reserve System Programme 2006 Evaluation by Brian Gilligan the National Reserve System Programme 2006 Evaluation by Brian Gilligan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019 Journal of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. In this issue: Variation in songs of the White-eared Honeyeater Phenotypic diversity in the Copperback Quailthrush and a third subspecies Neonicotinoid insecticides Bird Report, 2011-2015: Part 1, Non-passerines President: John Gitsham The South Australian Vice-Presidents: Ornithological John Hatch, Jeff Groves Association Inc. Secretary: Kate Buckley (Birds SA) Treasurer: John Spiers FOUNDED 1899 Journal Editor: Merilyn Browne Birds SA is the trading name of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. Editorial Board: Merilyn Browne, Graham Carpenter, John Hatch The principal aims of the Association are to promote the study and conservation of Australian birds, to disseminate the results Manuscripts to: of research into all aspects of bird life, and [email protected] to encourage bird watching as a leisure activity. SAOA subscriptions (e-publications only): Single member $45 The South Australian Ornithologist is supplied to Family $55 all members and subscribers, and is published Student member twice a year. In addition, a quarterly Newsletter (full time Student) $10 reports on the activities of the Association, Add $20 to each subscription for printed announces its programs and includes items of copies of the Journal and The Birder (Birds SA general interest. newsletter) Journal only: Meetings are held at 7.45 pm on the last Australia $35 Friday of each month (except December when Overseas AU$35 there is no meeting) in the Charles Hawker Conference Centre, Waite Road, Urrbrae (near SAOA Memberships: the Hartley Road roundabout). Meetings SAOA c/o South Australian Museum, feature presentations on topics of ornithological North Terrace, Adelaide interest. -

THE C&WM NEWS March 2019

THE C&WM NEWS March 2019 General Meeting Wednesday 13th March 7.00 pm at GAZA Sports & Community Club Corner of Main North East Rd and Wellington St Klemzig Secretary’s scribble SSAA membership Password for CWM webpage Membership to SSAA is mandatory in order to maintain As you are aware, we have locked down our webpage membership to CWM (SA). We are a branch of SSAA and from non-members in an attempt to preserve our this is reflected in our Constitution. intellectual property. The current password is going to change shortly and we’ll let you know what it is when Many members fail to inform us of the expiry date of that occurs. When you enter the password, as it currently their SSAA membership when lodging CWM renewals and stands, please ensure there are no spaces at the most fail to inform us they have renewed membership. beginning of the word or, after it. It may create a space We do not have access to the SSAA database and will when you click in the box to type the password, so likely never get it, so it’s critical that you manage this double check by hitting the backspace key. This will process yourselves. delete any spaces that may have been inadvertently created. The password works, so if you are having While occasionally we can carry out an internal problems, it’s likely PEBKAC – You. verification at any given moment in time, that’s only reliable up to that date. Therefore, we would not know if Notebook covers members whose SSAA membership expires the end of Off the back of an initiative thought of a few years ago by say February, have renewed. -

SA Arid Lands

June 2014 Issue 70 ACROSS THE OUTBACK SA Arid Lands: ‘It’s your 01 BOARD NEWS 02 Help is on the way for drought affected properties in place – tell us what matters South Australia 03 NRM Board tours region 03 Pastoral Board hosts open forum to you!’ in Glendambo 05 LAND MANAGEMENT The SA Arid Lands community is being asked to share their 06 LambEx 2014 motivates and informs treasured spots and their childhood memories — and it’s land managers 07 Wirrealpa and Willow Springs host all about taking a new approach to planning for the future EMU™ Field Day of the region. 08 VOLUNTEERS The SA Arid Lands (SAAL) Natural Resources This is why we have a Regional NRM Plan, 08 The Great Tracks Clean Up Crew get Management (NRM) Board has taken its to articulate our goals and to set the off the beaten track first step in working with the community direction of natural resource management to develop the new Regional NRM Plan, for the region.’ 09 WATER MANAGEMENT launching ‘It’s your place’, a campaign that While there is an existing Plan in place, 09 Managing South Australia’s encourages community to come together to it needs updating to account for climate Diamantina River catchment talk about what makes the SA Arid Lands change as well as legislative, policy and 10 THREATENED FAUNA region such a special place. organisational changes, so the SAAL NRM 10 Trial Western Quoll release – an ‘The role of the NRM Board is to champion Board is using the opportunity to improve update sustainable use of our natural resources — community input and ownership. -

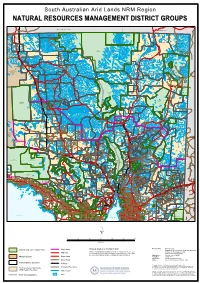

Natural Resources Management District Groups

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region NNAATTUURRAALL RREESSOOUURRCCEESS MMAANNAAGGEEMMEENNTT DDIISSTTRRIICCTT GGRROOUUPPSS NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Mount Dare H.S. CROWN POINT Pandie Pandie HS AYERS SIMPSON DESERT RANGE SOUTH Tieyon H.S. CONSERVATION PARK ALTON DOWNS TIEYON WITJIRA NATIONAL PARK PANDIE PANDIE CORDILLO DOWNS HAMILTON DEROSE HILL Hamilton H.S. SIMPSON DESERT KENMORE REGIONAL RESERVE Cordillo Downs HS PARK Lambina H.S. Mount Sarah H.S. MOUNT Granite Downs H.S. SARAH Indulkana LAMBINA Todmorden H.S. MACUMBA CLIFTON HILLS GRANITE DOWNS TODMORDEN COONGIE LAKES Marla NATIONAL PARK Mintabie EVERARD PARK Welbourn Hill H.S. WELBOURN HILL Marla - Oodnadatta INNAMINCKA ANANGU COWARIE REGIONAL PITJANTJATJARAKU Oodnadatta RESERVE ABORIGINAL LAND ALLANDALE Marree - Innamincka Wintinna HS WINTINNA KALAMURINA Innamincka ARCKARINGA Algebuckinna Arckaringa HS MUNGERANIE EVELYN Mungeranie HS DOWNS GIDGEALPA THE PEAKE Moomba Evelyn Downs HS Mount Barry HS MOUNT BARRY Mulka HS NILPINNA MULKA LAKE EYRE NATIONAL MOUNT WILLOUGHBY Nilpinna HS PARK MERTY MERTY Etadunna HS STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION ETADUNNA TALLARINGA PARK RESERVE CONSERVATION Mount Clarence HS PARK COOBER PEDY COMMONAGE William Creek BOLLARDS LAGOON Coober Pedy ANNA CREEK Dulkaninna HS MABEL CREEK DULKANINNA MOUNT CLARENCE Lindon HS Muloorina HS LINDON MULOORINA CLAYTON Curdimurka MURNPEOWIE INGOMAR FINNISS STUARTS CREEK SPRINGS MARREE ABORIGINAL Ingomar HS LAND CALLANNA Marree MUNDOWDNA LAKE CALLABONNA COMMONWEALTH HILL FOSSIL MCDOUAL RESERVE PEAK Mobella -

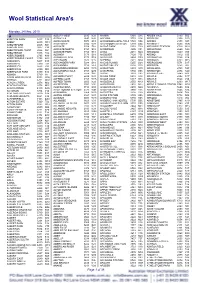

Wool Statistical Area's

Wool Statistical Area's Monday, 24 May, 2010 A ALBURY WEST 2640 N28 ANAMA 5464 S15 ARDEN VALE 5433 S05 ABBETON PARK 5417 S15 ALDAVILLA 2440 N42 ANCONA 3715 V14 ARDGLEN 2338 N20 ABBEY 6280 W18 ALDERSGATE 5070 S18 ANDAMOOKA OPALFIELDS5722 S04 ARDING 2358 N03 ABBOTSFORD 2046 N21 ALDERSYDE 6306 W11 ANDAMOOKA STATION 5720 S04 ARDINGLY 6630 W06 ABBOTSFORD 3067 V30 ALDGATE 5154 S18 ANDAS PARK 5353 S19 ARDJORIE STATION 6728 W01 ABBOTSFORD POINT 2046 N21 ALDGATE NORTH 5154 S18 ANDERSON 3995 V31 ARDLETHAN 2665 N29 ABBOTSHAM 7315 T02 ALDGATE PARK 5154 S18 ANDO 2631 N24 ARDMONA 3629 V09 ABERCROMBIE 2795 N19 ALDINGA 5173 S18 ANDOVER 7120 T05 ARDNO 3312 V20 ABERCROMBIE CAVES 2795 N19 ALDINGA BEACH 5173 S18 ANDREWS 5454 S09 ARDONACHIE 3286 V24 ABERDEEN 5417 S15 ALECTOWN 2870 N15 ANEMBO 2621 N24 ARDROSS 6153 W15 ABERDEEN 7310 T02 ALEXANDER PARK 5039 S18 ANGAS PLAINS 5255 S20 ARDROSSAN 5571 S17 ABERFELDY 3825 V33 ALEXANDRA 3714 V14 ANGAS VALLEY 5238 S25 AREEGRA 3480 V02 ABERFOYLE 2350 N03 ALEXANDRA BRIDGE 6288 W18 ANGASTON 5353 S19 ARGALONG 2720 N27 ABERFOYLE PARK 5159 S18 ALEXANDRA HILLS 4161 Q30 ANGEPENA 5732 S05 ARGENTON 2284 N20 ABINGA 5710 18 ALFORD 5554 S16 ANGIP 3393 V02 ARGENTS HILL 2449 N01 ABROLHOS ISLANDS 6532 W06 ALFORDS POINT 2234 N21 ANGLE PARK 5010 S18 ARGYLE 2852 N17 ABYDOS 6721 W02 ALFRED COVE 6154 W15 ANGLE VALE 5117 S18 ARGYLE 3523 V15 ACACIA CREEK 2476 N02 ALFRED TOWN 2650 N29 ANGLEDALE 2550 N43 ARGYLE 6239 W17 ACACIA PLATEAU 2476 N02 ALFREDTON 3350 V26 ANGLEDOOL 2832 N12 ARGYLE DOWNS STATION6743 W01 ACACIA RIDGE 4110 Q30 ALGEBUCKINA -

Bush Heritage News | Winter 2012 3 Around Your Reserves in 90 Days Your Support Makes a Difference in So Many Ways, Every Day, All Across Australia

In this issue BUSH 3 A year at Carnarvon 4 Around your reserves 6 Her bush memory HERITAGE 7 Easter on Boolcoomatta NEWS 8 From the CEO Winter 2012 www.bushheritage.org.au Your wombat refuge The woodlands and saltlands of your Bon Bon Station Reserve are home to the southern hairy-nosed wombat. These endearing creatures have presented reserve manager Glen Norris with a tricky challenge. Lucy Ashley reports Glen Norris has worked as reserve manager – and he has to work out how to do this “It’s important we reduce rabbit in charge of protecting over 200,000 without harming the wombats, or their hectares of sprawling desert, saltlands, precious burrows. populations, and soon,” says wetlands and woodlands at Bon Bon The ultimate digging machine Glen. “Thanks to lots of help Station Reserve in South Australia for two-and-a-half years. Smaller than their cousin the common from Bush Heritage supporters wombat, southern hairy-nosed wombats Right now, he has a tricky situation on his have soft, fluffy fur (even on their nose), since we bought Bon Bon and hands. long sticky-up ears and narrow snouts. de-stocked it, much of the land Glen has to remove a large population of With squat, strongly built bodies and short highly destructive feral rabbits from legs ending in large paws with strong is now in great condition.” underground warren systems that they’re blade-like claws, they are the ultimate currently sharing with a population of marsupial digging machine. Photograph by Steve Parish protected southern hairy-nosed wombats How you’ve help created a refuge for Bon Bon’s wombats and other native animals • Purchase of the former sheep station in 2008 • Removal of sheep and repair of boundary fences to keep neighbour’s stock out • Control of recent summer bushfires • Soil conservation works to reduce erosion • Ongoing management of invasive weeds like buffel grass • Control programs for rabbits, foxes and feral cats. -

Motorists Obtain 15000 Milesfrom

This sampler file contains various sample pages from the product. Sample pages will often include: the title page, an index, and other pages of interest. This sample is fully searchable (read Search Tips) but is not FASTFIND enabled. To view more samplers click here www.gould.com.au www.archivecdbooks.com.au · The widest range of Australian, English, · Over 1600 rare Australian and New Zealand Irish, Scottish and European resources books on fully searchable CD-ROM · 11000 products to help with your research · Over 3000 worldwide · A complete range of Genealogy software · Including: Government and Police 5000 data CDs from numerous countries gazettes, Electoral Rolls, Post Office and Specialist Directories, War records, Regional Subscribe to our weekly email newsletter histories etc. FOLLOW US ON TWITTER AND FACEBOOK www.unlockthepast.com.au · Promoting History, Genealogy and Heritage in Australia and New Zealand · A major events resource · regional and major roadshows, seminars, conferences, expos · A major go-to site for resources www.familyphotobook.com.au · free information and content, www.worldvitalrecords.com.au newsletters and blogs, speaker · Free software download to create biographies, topic details · 50 million Australasian records professional looking personal photo books, · Includes a team of expert speakers, writers, · 1 billion records world wide calendars and more organisations and commercial partners · low subscriptions · FREE content daily and some permanently This sampler file includes the title page and various sample pages from this volume. This file is fully searchable (read search tips page) Archive CD Books Australia exists to make reproductions of old books, documents and maps available on CD to genealogists and historians, and to co-operate with family history societies, libraries, museums and record offices to scan and digitise their collections for free, and to assist with renovation of old books in their collection. -

Celebrating 25 Years of Across the Outback

April 2015 Issue 73 ACROSS THE OUTBACK Celebrating 25 years of 01 BOARD NEWS 02 Kids share what they love about their place Across The Outback 03 Act locally – join your NRM Group 04 Seasonal conditions report Welcome to the first edition of Across The Outback 05 LAND MANAGEMENT for 2015. 05 Commercial camel grazing This 73rd edition marks 25 years since The page is about natural resources on pastoral properties Across The Outback first rolled off the management in its truest sense – it’s 06 THREATENED SPECIES press as Outback, published by the about promoting healthy communities then Department of Lands on behalf and sustainable industries as much as 07 Idnya update of the Pastoral Board for the South environment and conservation news. 07 ABORIGINAL NRM NEWS Australian pastoral industry. Think community events, tourism 08 WATER MANAGEMENT The publication has seen changing news, information about road and covers and faces, and changes to park closures, and items for pastoralists 08 Sharing knowledge on the government and departments, but its on improving their (sustainable) Diamantina River Channel Country commitment to keep the SA Arid Lands production. 09 PEST MANAGEMENT community informed of government Continued on page 02… activities which affect them has 09 Buffel Grass declared in South Australia remained the same. And it remains the only publication 10 NRM GROUP NEWS that covers and centres on the SA Arid 12 PLANNING FOR WILD DOGS Lands region. Across The Outback is mailed to 14 NATIONAL PARKS about 1500 subscribers – through 14 A new management plan for email and via snail mail – and while Innamincka Regional Reserve its readership is many and varied, and includes conservation, recreation and 15 ANIMAL HEALTH tourist groups, its natural resources 16 OUTBACK COMMUNITY management focus has meant its core readership remains the region’s pastoral community. -

Boolcoomatta Reserve CLICK WENT the SHEARS

Boolcoomatta Reserve CLICK WENT THE SHEARS A social history of Boolcoomatta Station, 1857 to 2020 Judy D. Johnson Editor: Eva Finzel Collated and written by Judy Johnson 2019 Edited version by Eva Finzel 2021 We acknowledge the Adnyamathanha People and Wilyakali People as the Traditional Owners of what we know as Boolcoomatta. We recognise and respect the enduring relationship they have with their lands and waters, and we pay our respects to Elders past, present and future. Front page map based on Pastoral Run Sheet 5, 1936-1964, (163-0031) Courtesy of the State Library of South Australia Bush Heritage Australia Level 1, 395 Collins Street | PO Box 329 Flinders Lane Melbourne, VIC 8009 T: (03) 8610 9100 T: 1300 628 873 (1300 NATURE) F: (03) 8610 9199 E: [email protected] W: www.bushheritage.org.au Content Author’s note and acknowledgements viii Editor’s note ix Timeline, 1830 to 2020 x Conversions xiv Abbreviations xiv An introduction to Boolcoomatta 1 The Adnyamathanha People and Wilyakali People 4 The European history of Boolcoomatta 6 European settlement 6 From sheep station to a place of conservation 8 Notes 9 Early explorers, surveyors and settlers, 1830 to 1859 10 Early European exploration and settlement 10 Goyder’s discoveries and Line 11 Settlement during the 1800s 13 The shepherd and the top hats The Tapley family, 1857 to 1858 14 The shepherds 15 The top hats 16 The Tapleys’ short lease of Boolcoomatta 16 Thomas and John E Tapley's life after the sale of Boolcoomatta 17 Boolcoomatta’s neighbours in 1857 18 The timber -

Across the October 2019

ACROSS THE OUTBACKOCTOBER 2019 HEIDI WHO PHOTOGRAPHY WHO HEIDI Natural Resources SA Arid Lands | 01 From the Board On behalf of myself and the board members finishing their terms I would like to reflect on our time and say a few farewell words. Our time on the SA Arid Lands NRM Board One major Board responsibility is the Contents has been both rewarding and challenging. requirement to prepare a 10-year strategic The SAAL NRM region is one of the larger NRM plan for the region. 02 FROM THE BOARD NRM regions in Australia, covering more The SAAL Board recently released the 03 REGIONAL MANAGER UPDATE than 50% of South Australia. With a small second 10-year regional NRM plan. In population the SAAL region has a relatively preparing the plan the Board took an 04 NRM KIDS small levy base to reinvest in NRM over a entirely new approach focussing on 05 KANGAROO IMPACT STUDY IN huge area. As a result, the Board has always capturing the things most valued by our NORTH EAST been heavily reliant on our community community, incorporating them into an and other partners for their goodwill, adaptive management approach. In doing 05 COMMUNITY GRANTS AWARDED and stewardship to assist in achieving the so the Board consulted widely with the 06 RED MEAT PRODUCTION IN A Board’s goals. community and its stakeholders and we are CHANGING CLIMATE The NRM model has undergone major very proud of the final product, which will 07 PEST CONTROL SUCCESS changes over the years, through the provide the new Landscape Board with a integration of the NRM Boards with the useful framework to work from. -

Bounceback 20 Year Report

celebrating 20 years R Sleep building resilience across the ranges 1 The South Australian Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources acknowledges the Adnyamathanha, Bangarla, Ngadjuri, Nukunu and Kokatha peoples as the traditional custodians of the lands, waters, plants and animals, in the areas where BOUNCEBACK operates. We recognise and respect that traditional lands or ‘country’ are central to the spiritual lives and living culture of these peoples. We aspire to a positive future based on a greater understanding between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians and endeavour to build strong relationships with Aboriginal peoples based on mutual courtesy, respect and equity. We will continue to work cooperatively with Aboriginal peoples to conserve country, plants, animals and culture, and strive to achieve reconciliation in our daily work. Several of the reserves within the Bounceback footprint are co-managed by the SA Government and Traditional Owners. celebrating 20 years 20 celebrating Bounceback will work closely with local Aboriginal communities to ensure that traditional knowledge and aspirations are included in its BOUNCEBACK future programs. 2 In 2012, BOUNCEBACK celebrates its twentieth year. The landscapes of the Flinders, Gawler and Olary Ranges are BOUNCEBACK is a landscape spectacular, with their dramatic scenery, accessible wildlife scale conservation program, and diverse vegetation. However, most visitors would not be delivering on NatureLinks, that aware that they are looking at highly altered landscapes. aims to protect and restore the semi-arid environments of When species vanish they do so silently, In the early 1990s, a small group of rangers the Flinders, Olary and Gawler slipping away unnoticed. Absences have and wildlife managers recognized the need Ranges in South Australia. -

Delivering Natural Resource Management in the SA Arid Lands

Protecting our land, plants and animals On Track Understanding and securing our water resources Delivering natural resource management Supporting our industries in the SA Arid Lands 2012-13 and communities PAUL WAINWRIGHT PAUL Banded Stilts Welcome WAINWRIGHT PAUL Welcome to the third edition of On Track. It’s been another busy year for the South The Board also took a strategic look ahead, updating its Australian Arid Lands (SAAL) Natural Business Plan to define its priorities for the next three years. Resources Management (NRM) Board, and These priorities are reviewed annually in consultation with our on behalf of the Board I am pleased to NRM Groups and partners to ensure they remain current. release On Track, our annual report to our Our current priorities include delivering on-ground results, community and partners on the important developing community partnerships, investing in research, achievements which deliver on our goals looking at innovative approaches to community involvement, defined in the SAAL Regional NRM Plan. securing funding for our key projects, and meeting our legal True to the guiding role of the Board and responsibilities surrounding the management of natural our Plan, On Track again pays tribute to resources. the wide variety of organisations and On behalf of the Board, I thank our land managers, individuals who are contributing to natural community, volunteers, NRM Groups, levy-payers, funding resource management in the SA Arid Lands bodies and partner organisations for their efforts in region and helping to meet our targets. contributing to the sustainable management of our region’s Collectively, we work to manage our natural resources and I look forward to your continued region’s pest plants and animals, protect support and involvement.