Through the Eyes of Tom Joad: Patterns of American Idealism, Bob Dylan, and the Folk Protest Movement James Dunlap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unobtainium-Vol-1.Pdf

Unobtainium [noun] - that which cannot be obtained through the usual channels of commerce Boo-Hooray is proud to present Unobtainium, Vol. 1. For over a decade, we have been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We invite you to our space in Manhattan’s Chinatown, where we encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections by appointment or chance. Please direct all inquiries to Daylon ([email protected]). Terms: Usual. Not onerous. All items subject to prior sale. Payment may be made via check, credit card, wire transfer or PayPal. Institutions may be billed accordingly. Shipping is additional and will be billed at cost. Returns will be accepted for any reason within a week of receipt. Please provide advance notice of the return. Please contact us for complete inventories for any and all collections. The Flash, 5 Issues Charles Gatewood, ed. New York and Woodstock: The Flash, 1976-1979. Sizes vary slightly, all at or under 11 ¼ x 16 in. folio. Unpaginated. Each issue in very good condition, minor edgewear. Issues include Vol. 1 no. 1 [not numbered], Vol. 1 no. 4 [not numbered], Vol. 1 Issue 5, Vol. 2 no. 1. and Vol. 2 no. 2. Five issues of underground photographer and artist Charles Gatewood’s irregularly published photography paper. Issues feature work by the Lower East Side counterculture crowd Gatewood associated with, including George W. Gardner, Elaine Mayes, Ramon Muxter, Marcia Resnick, Toby Old, tattooist Spider Webb, author Marco Vassi, and more. -

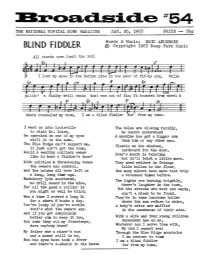

BLIND FIDDLER © Copyright 1965 Deep Fork Husic

c:l.si THE NATIONAL TOPICAL SONG MAGAZINE JAN. 20, 1965 PRICE -- 50¢ Words & Music: ERIC ANDERSEN BLIND FIDDLER © Copyright 1965 Deep Fork Husic All chords open (omit the 3rd) there concealed my doom, I am a blind fiddler . ar from my home. I went up into Louisville The holes are closing rapidly, to visit Dr. Laine, he cannot understand He operated on one of my eyes A machine has got a bigger arm still it is the same. than him or ~ other man. The Blue Ridge can't support me, Plastic on the ,windows, it just ain't got the room, cardboard for the door, Would a wealthy colliery owner Baby's mouth is twisting like to hear a fiddler's tune? but it'll twist a little more. With politics & threatening tones They need welders in Chicago the owners can control, falls hollow to the floor, And the unions all have left us How many miners have made that trip a long, long time ago. a thousand times before. Machinery ~in scattered, The lights are burning brightly, nCOJ drill sound in the mine, there's laughter in the town, For all the good a collier is But the streets are dark and empty, you might as well be blind. ain I t a miner to be found. Was a time I worked a long 14 They're in some lonesome holler for a short 8 bucks a day. where the sun refuse to shine, You I re lucky if you're workin A baby's cries are muffled that's what the owners say. -

Robert Glasper's In

’s ION T T R ESSION ER CLASS S T RO Wynton Marsalis Wayne Wallace Kirk Garrison TRANSCRIP MAS P Brass School » Orbert Davis’ Mission David Hazeltine BLINDFOLD TES » » T GLASPE R JAZZ WAKE-UP CALL JAZZ WAKE-UP ROBE SLAP £3.50 £3.50 U.K. T.COM A Wes Montgomery Christian McBride Wadada Leo Smith Wadada Montgomery Wes Christian McBride DOWNBE APRIL 2012 DOWNBEAT ROBERT GLASPER // WES MONTGOMERY // WADADA LEO SmITH // OrbERT DAVIS // BRASS SCHOOL APRIL 2012 APRIL 2012 VOLume 79 – NumbeR 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Managing Editor Bobby Reed News Editor Hilary Brown Reviews Editor Aaron Cohen Contributing Editors Ed Enright Zach Phillips Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Assistant Theresa Hill 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point, Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Or- leans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. -

88-Page Mega Version 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010

The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! 88-PAGE MEGA VERSION 2017 2016 2015 2014 2013 2012 2011 2010 COMBINED jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com The Gift Guide YEAR-LONG, ALL OCCCASION GIFT IDEAS! INDEX 2017 Gift Guide •••••• 3 2016 Gift Guide •••••• 9 2015 Gift Guide •••••• 25 2014 Gift Guide •••••• 44 2013 Gift Guide •••••• 54 2012 Gift Guide •••••• 60 2011 Gift Guide •••••• 68 2010 Gift Guide •••••• 83 jazz &blues report jazz & blues report jazz-blues.com 2017 Gift Guide While our annual Gift Guide appears every year at this time, the gift ideas covered are in no way just to be thought of as holiday gifts only. Obviously, these items would be a good gift idea for any occasion year-round, as well as a gift for yourself! We do not include many, if any at all, single CDs in the guide. Most everything contained will be multiple CD sets, DVDs, CD/DVD sets, books and the like. Of course, you can always look though our back issues to see what came out in 2017 (and prior years), but none of us would want to attempt to decide which CDs would be a fitting ad- dition to this guide. As with 2016, the year 2017 was a bit on the lean side as far as reviews go of box sets, books and DVDs - it appears tht the days of mass quantities of boxed sets are over - but we do have some to check out. These are in no particular order in terms of importance or release dates. -

A New Annual Festival Celebrating the History and Heritage of Greenwich Village

A New Annual Festival Celebrating the History and Heritage of Greenwich Village OPENING RECEPTION IN THE VILLAGE TRIP LOUNGE An exhibition of work by celebrated music photographer David Gahr and rare Greenwich Village memorabilia from the collection of archivist Mitch Blank Music by David Amram, The Village Trip Artist-in-Residence Washington Square Hotel, Thursday September 27, at 6.30pm David Gahr (1922-2008) was destined for a career as an economics journalist but he got lost in music, opting to remain in New York City, at Sam Goody’s celebrated record store, because a staff job on New Republic would have meant moving to Washington DC, a prospect he found “a bit boring.” From his perch behind the counter, Gahr made sure to photograph the customers he recognised as musicians, quickly building up a portfolio. He turned professional in 1958 when Moses Asch, founder of Folkways Records – “that splendid, cantankerous guru of our time” - commissioned him to photograph such figures as Woody Guthrie, Cisco Houston and Pete Seeger. He went on to capture now-iconic images of the great American bluesmen - Big Bill Broonzy, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, and Howlin’ Wolf, musicians who were key influences on so many 1960s rock musicians. Gahr was soon the foremost photographer of the Greenwich Village jazz and folk scenes, chronicling the early years of musicians whose work would come to define the 1960s, among them Charles Mingus, Miles Davis, Odetta, Joan Baez, Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell and Patti Smith. He photographed Bob Dylan’s celebrated 1963 Newport Folk Festival debut and captured the legendary moment in 1965 when he went electric. -

May 1965 Sing Out, Songs from Berkeley, Irwin Silber

IN THIS ISSUE SONGS INSTRUMENTAL TECHNIQUES OF AMERICAN FOLK GUITAR - An instruction book on Carter Plcldng' and Fingerplcking; including examples from Elizabeth Cotten, There But for Fortune 5 Mississippi John Hurt, Rev. Gary Davis, Dave Van Ronk, Hick's Farewell 14 etc, Forty solos fUll y written out in musIc and tablature. Little Sally Racket 15 $2.95 plus 25~ handllng. Traditional stringed Instruments, Long Black Veil 16 P.O. Box 1106, Laguna Beach, CaUl. THE FOLK SONG MAGAZINE Man with the Microphone 21 SEND FOR YOUR FREE CATALOG on Epic hand crafted 'The Verdant Braes of Skreen 22 ~:~~~d~e Epic Company, 5658 S. Foz Circle, Littleton, VOL. 15, NO. 2 W ith International Section MAY 1965 75~ The Commonwealth of Toil 26 -An I Want Is Union 27 FREE BEAUTIFUL SONG. All music-lovers send names, Links on the Chain 32 ~~g~ ~ses . Nordyke, 6000-21 Sunset, Hollywood, call!. JOHNNY CASH MUDDY WATERS Get Up and Go 34 Long Thumb 35 DffiE CTORY OF COFFEE HOUSE S Across the Country ••• The Hell-Bound Train 38 updated edition covers 150 coffeehouses: addresses, des criptions, detaUs on entertaInment policies. $1 .00. TaUs Beans in My Ears 45 man Press, Boz 469, Armonk, N. Y. (Year's subscription Cannily, Cannily 46 to supplements $1.00 additional). ARTICLES FOLK MUSIC SUPPLIE S: Records , books, guitars, banjos, accessories; all available by mall. Write tor information. Denver Folklore Center, 608 East 17th Ave., Denver 3, News and Notes 2 Colo. R & B (Tony Glover) 6 Son~s from Berkeley NAKADE GUITARS - ClaSSical, Flamenco, Requinta. -

The Folk Music Revival and the Counter Culture: Contributions and Contradictions Author(S): Jens Lund and R

The Folk Music Revival and the Counter Culture: Contributions and Contradictions Author(s): Jens Lund and R. Serge Denisoff Source: The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 84, No. 334 (Oct. - Dec., 1971), pp. 394-405 Published by: American Folklore Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/539633 . Accessed: 22/09/2011 16:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Folklore Society is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of American Folklore. http://www.jstor.org JENS LUND and R. SERGE DENISOFF The Folk Music Revival and the Counter Culture: Contributionsand Contradictions' OBSERVERS OF THE SO-CALLED "COUNTER CULTURE" have tended to portray this phenomenonas a new and isolated event. TheodoreRoszak, as well as nu- merousmusic and art historians,have cometo view the "counterculture" as a new reactionto technicalexpertise and the embourgeoismentof growing segmentsof the Americanpeople.2 This position,it would appear,is basicallyindicative of the intellectual"blind men and the elephant"couplet, where a social fact or event is examinedapart from otherstructural phenomena. Instead, it is our contentionthat the "counterculture" or Abbie Hoffman's"Woodstock Nation" is an emergent realityor a productof all that camebefore, sui generis.More simply,the "counter culture"can best be conceptualizedas partof a long historical-intellectualprogres- sion beginningwith the "Gardenof Eden"image of man. -

No Direction Home

INTRODUCTION The first publication of No Direction Home in September 1986 marked INTRODUCTION the twenty-fifth anniversary of Robert Shelton’s celebrated New York Times review of “a bright new face in folk music.” 1 This new edition coincides with its fiftieth, and the seventieth birthday of its subject. Shelton’s 400 words, the four-column headline announcing the arrival of “Bob Dylan: A Distinctive Folk- Song Stylist,” described a young man “bursting at the seams with talent” whose past mattered less than his future. Its prescience was remarkable, for Dylan’s talent was raw indeed and three record companies had failed to spot his potential. The fourth, Columbia, offered him a contract the day after the review appeared, before they had heard him sing a note. TAs Suze Rotolo reflected years later: “Robert Shelton’s review, without a doubt, made Dylan’s career … That review was unprecedented. Shelton had not given a review like that for anybody.” 2 In her memoir, A Freewheelin’ Time , Rotolo describes how she and Dylan bought an early edition of the Times at the kiosk on Sheridan Square and took it across the street to an all-night deli. “Then we went back and bought more copies.” 3 Yet Shelton never claimed to have “discovered” Dylan (“he discovered himself”) and, when his magnum opus was published, many friends and colleagues realized for the first time that the quiet American in their midst was rather more than simply a regional critic (Shelton was by then, somewhat implausibly, Arts Editor of the Brighton Evening Argus , a south-coast city daily). -

1 Bob Dylan's American Journey, 1956-1966 September 29, 2006, Through January 6, 2007 Exhibition Labels Exhibit Introductory P

Bob Dylan’s American Journey, 1956-1966 September 29, 2006, through January 6, 2007 Exhibition Labels Exhibit Introductory Panel I Think I’ll Call It America Born into changing times, Bob Dylan shaped history in song. “Life’s a voyage that’s homeward bound.” So wrote Herman Melville, author of the great tall tale Moby Dick and one of the American mythmakers whose legacy Bob Dylan furthers. Like other great artists this democracy has produced, Dylan has come to represent the very historical moment that formed him. Though he calls himself a humble song and dance man, Dylan has done more to define American creative expression than anyone else in the past half-century, forming a new poetics from his emblematic journey. A small town boy with a wandering soul, Dylan was born into a post-war landscape of possibility and dread, a culture ripe for a new mythology. Learning his craft, he traveled a road that connected the civil rights movement to the 1960s counterculture and the revival of American folk music to the creation of the iconic rock star. His songs reflected these developments and, resonating, also affected change. Bob Dylan, 1962 Photo courtesy of John Cohen Section 1: Hibbing Red Iron Town Bobby Zimmerman was a typical 1950’s kid, growing up on Elvis and television. Northern Minnesota seems an unlikely place to produce an icon of popular music—it’s leagues away from music birthplaces like Memphis and New Orleans, and seems as cold and characterless as the South seems mysterious. Yet growing up in the small town of Hibbing, Bob Dylan discovered his musical heritage through radio stations transmitting blues and country from all over, and formed his own bands to practice the newfound religion of rock ‘n’ roll. -

U.S. Postal Service Honors Groundbreaking Singer Janis Joplin on Limited-Edition Forever Stamp Stamp Available Today Online and at Post Offices Nationwide

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE National Media Contact: Roy Betts Aug. 8, 2014 202-268-3207 [email protected] Local Media Contact: James Wigdel 415-550-5718 [email protected] usps.com/news U.S. Postal Service Honors Groundbreaking Singer Janis Joplin on Limited-Edition Forever Stamp Stamp Available Today Online and at Post Offices Nationwide To obtain a high-resolution image of the stamp for media use only, email [email protected]. SAN FRANCISCO — The U.S. Postal Service today added legendary singer Janis Joplin to its Music Icons Forever Stamp series during a first-day-of-issue ceremony at the Outside Lands Music Festival at Golden Gate Park. “Today we salute an American original, Janis Joplin,” said Megan Brennan, chief operating officer and executive vice president. “I am honored to dedicate this stamp to pay tribute to one of the most important musicians of the 20th century.” The Janis Joplin Forever Stamp is the fifth in the Postal Service’s Music Icons series. Through 2 the power of stamps, Joplin joins a list of celebrated artists so honored: Lydia Mendoza, Johnny Cash, Ray Charles and Jimi Hendrix. “The recognition of her legacy and persona on such a permanent and iconic symbol as a United States postage stamp is truly humbling and it fills us with joy and pride,” said Michael Joplin, Joplin’s brother, who attended the stamp dedication ceremony. “I am happy for Janis that her image stands strong, representing the power, artistry and independence of women, said Joplin’s sister, Laura Joplin, in reflecting on the issuance of this stamp. -

“It Ain't the Melodies That're Important Man, It's the Words”

“It ain’t the melodies that’re important man, it’s the words”: Dylan’s use of figurative language in The Times They Are A-Changin’ and Highway 61 Revisited ”Det är inte melodierna som är viktiga, det är orden”: Dylans användning av figurativt språk i The Times They Are A-Changin’ och Highway 61 Revisited Jacob Forsberg Fakulteten för humaniora och samhällsvetenskap English 15 Points Supervisor: Åke Bergvall Examiner: Elisabeth Wennö 2016-03-14 C-Essay Jacob Forsberg Supervisor: Åke Bergvall Abstract This essay compares the figurative language of Bob Dylan’s albums The Times They Are A- Changin’ (1964) and Highway 61 Revisited (1965), with a focus on how Dylan remained engaged with societal injustices and human rights as he switched from acoustic to fronting a rock ‘n’ roll band. The essay argues that Dylan kept his critical stance on social issues, and that the poet’s usage of figurative language became more expressive and complex in the later album. In the earlier album Dylan’s critique, as seen in his use of figurative language, is presented in a more obvious manner in comparison to Highway 61 Revisited, where the figurative language is more vivid, and with a more embedded critical stance. Uppsatsen jämför det figurativa språket i Bob Dylans skivor The Times They Are A-Changin’ (1964) och Highway 61 Revisited (1965), med ett fokus på hur Dylan fortsatte vara engagerad inom samhällsfrågor och mänskliga rättigheter när han gick över från akustisk solomusik till att leda ett rockband. Uppsatsen argumenterar för att Dylan behöll sin kritiska syn på samhällsfrågor, och att poetens användning av figurativt språk blev mer expressivt och komplext i det senare albumet. -

Download Spring 2020

TABLE OF CONTENTS RIZZOLI 50 Lessons to Learn from Frank Lloyd Wright . .17 Rashid Al Khalifa: Full Circle . .45 Alicia Rountree: Fresh Island Style . .25 Rika’s Japanese Home Cooking . .22 The Appalachian Trail . .54 Rooms of Splendor . .18 At Home in the English Countryside: Schumann’s Whisk(e)y Lexicon . .26 Designers and Their Dogs . .2 Scott Mitchell Houses . .10 Automobili Lamborghini . .51 Sicily . .56 The Best Things to Do in Los Angeles: Revised Edition . .52 Skylines of New York . .54 The Candy Book of Transversal Creativity . .34 Taking Time . .44 Christian Louboutin: Exhibition . .27 Voyages Intérieurs . .16 Classicism at Home . .19 Watches International Vol. XXI . .50 Climbing Bare . .41 Wayne Thiebaud Mountains . .42 The Cobrasnake: All Yesterday’s Parties . .35 We Protest . .33 Dan Colen . .46 Wine Country Living . .11 de Gournay: Art on the Walls . .5 The Women’s Heritage Sourcebook . .21 Decorate Happy . .4 You’re Invited . .20 Design Fix . .8 Zeng Fanzhi: Untitled . .43 Designing History . .3 Diana Vreeland: Bon Mots . .28 RIZZOLI ELECTA Dior Joaillerie . .29 Alice Trumbull Mason . .73 Elan: The Interior Design on Kate Hume . .15 Alma Allen . .72 Eva Hesse and Hannah Wilke . .42 At First Light . .66 Eyes Over the World . .37 BATA Shoe Museum . .65 Federico Fellini . .38 Bosco Sodi . .70 From the Archive: RIMOWA . .49 City/Game . .63 Futura . .36 David Wiseman . .62 Garden Design Master Class . .6 A Garden for All Seasons . .77 Gathering . .24 I Was a Teenage Banshee . .75 Hamilton: Portraits of a Revolution . .31 Laurent Grasso . .74 The Heart of Cooking . .50 Lens on American Art .