UNC Thesis Submission Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Various Lonesome Valley (A Collection of American Folk Music) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Lonesome Valley (A Collection Of American Folk Music) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Folk, World, & Country Album: Lonesome Valley (A Collection Of American Folk Music) Country: US Released: 2006 Style: Country, Folk MP3 version RAR size: 1863 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1640 mb WMA version RAR size: 1961 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 913 Other Formats: ASF MIDI XM AIFF AUD APE AC3 Tracklist 1 –Pete Seeger, Bess Lomax, Tom Glazer Down In The Valley 2:35 2 –Cisco Houston The Rambler 3:18 3 –Butch Hawes Arthritis Blues 3:23 4 –Pete Seeger, Bess Lomax, Tom Glazer Polly Wolly Doodle 1:55 5 –Lee Hays, Pete Seeger, Bess Lomax Lonesome Traveler 1:55 6 –Cisco Houston On Top Of Old Smoky 1:35 7 –Pete Seeger Black Eyed Suzie 2:12 8 –Woody Guthrie Cowboy Waltz 2:06 9 –Cisco Houston and Woody Guthrie Sowing On The Mountain 2:29 Companies, etc. Copyright (c) – Folkways Records & Service Corp. Copyright (c) – Smithsonian Folkways Recordings Phonographic Copyright (p) – Smithsonian Folkways Recordings Credits Artwork – Carlis* Notes Professionally printed CDr on-demand reissue of the 1950/1958 10'' release on Folkways Records. The enhanced CDr includes a PDF file of the booklet included with the original release. © 1950 Folkways Records & Service Corp. ℗ © 2006 Smithsonian Folkways Recordings Total time: 21 min. Gatefold cardboard sleeve. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Scanned): 093070201026 Label Code: LC 9628 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year FP 10 Various Lonesome Valley (10") Folkways Records FP 10 US 1951 FA 2010 Various Lonesome Valley (10") Folkways Records FA 2010 US 1958 FP 10 Various Lonesome Valley (10") Folkways Records FP 10 US 1951 Related Music albums to Lonesome Valley (A Collection Of American Folk Music) by Various Pete Seeger - Birds, Beasts, Bugs and Little Fishes Pete Seeger And Frank Hamilton - Nonesuch And Other Folk Tunes Lead Belly - Shout On (Lead Belly Legacy Vol. -

Sòouünd Póetry the Wages of Syntax

SòouÜnd Póetry The Wages of Syntax Monday April 9 - Saturday April 14, 2018 ODC Theater · 3153 17th St. San Francisco, CA WELCOME TO HOTEL BELLEVUE SAN LORENZO Hotel Spa Bellevue San Lorenzo, directly on Lago di Garda in the Northern Italian Alps, is the ideal four-star lodging from which to explore the art of Futurism. The grounds are filled with cypress, laurel and myrtle trees appreciated by Lawrence and Goethe. Visit the Mart Museum in nearby Rovareto, designed by Mario Botta, housing the rich archive of sound poet and painter Fortunato Depero plus innumerable works by other leaders of that influential movement. And don’t miss the nearby palatial home of eccentric writer Gabriele d’Annunzio. The hotel is filled with contemporary art and houses a large library https://www.bellevue-sanlorenzo.it/ of contemporary art publications. Enjoy full spa facilities and elegant meals overlooking picturesque Lake Garda, on private grounds brimming with contemporary sculpture. WElcome to A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC The 23rd Other Minds Festival is presented by Other Minds in 2 Message from the Artistic Director association with ODC Theater, 7 What is Sound Poetry? San Francisco. 8 Gala Opening All Festival concerts take place at April 9, Monday ODC Theater, 3153 17th St., San Francisco, CA at Shotwell St. and 12 No Poets Don’t Own Words begin at 7:30 PM, with the exception April 10, Tuesday of the lecture and workshop on 14 The History Channel Tuesday. Other Minds thanks the April 11, Wednesday team at ODC for their help and hard work on our behalf. -

An Investigation of the Perceived Impact of the Inclusion of Steel Pan Ensembles in Collegiate Curricula in the Midwest

AN INVESTIGATION OF THE PERCEIVED IMPACT OF THE INCLUSION OF STEEL PAN ENSEMBLES IN COLLEGIATE CURRICULA IN THE MIDWEST by BENJAMIN YANCEY B.M., University of Central Florida, 2009 A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MUSIC School of Music, Theatre and Dance College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2014 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. Kurt Gartner Abstract The current study is an in depth look of the impact of steel pan ensemble within the college curriculum of the Midwest. The goal of the study is to further understand what perceived impacts steel pan ensemble might have on student learning through the perceptions of both instructors and students. The ensemble's impact on the students’ senses of rhythm, ability to listen and balance in an ensemble, their understanding of voicing and harmony, and appreciation of world music were all investigated through both the perceptions of the students as well as the instructors. Other areas investigated were the role of the instructor to determine how their teaching methods and topics covered impacted the students' opinion of the ensemble. This includes, but is not limited to, time spent teaching improvisation, rote teaching versus Western notation, and adding historical context by teaching the students the history of the ensemble. The Midwest region was chosen both for its high density of collegiate steel pan ensembles as well as its encompassing of some of the oldest pan ensembles in the U.S. The study used an explanatory mixed methodology employing two surveys, a student version and an instructor version, distributed to the collegiate steel pan ensembles of the Midwest via the internet. -

Repor 1 Resumes

REPOR 1RESUMES ED 018 277 PS 000 871 TEACHING GENERAL MUSIC, A RESOURCE HANDBOOK FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. BY- SAETVEIT, JOSEPH G. AND OTHERS NEW YORK STATE EDUCATION DEPT., ALBANY PUB DATE 66 EDRS PRICEMF$0.75 HC -$7.52 186P. DESCRIPTORS *MUSIC EDUCATION, *PROGRAM CONTENT, *COURSE ORGANIZATION, UNIT PLAN, *GRADE 7, *GRADE 8, INSTRUCTIONAL MATERIALS; BIBLIOGRAPHIES, MUSIC TECHNIQUES, NEW YORK, THIS HANDBOOK PRESENTS SPECIFIC SUGGESTIONS CONCERNING CONTENT, METHODS, AND MATERIALS APPROPRIATE FOR USE IN THE IMPLEMENTATION OF AN INSTRUCTIONAL PROGRAM IN GENERAL MUSIC FOR GRADES 7 AND 8. TWENTY -FIVE TEACHING UNITS ARE PROVIDED AND ARE RECOMMENDED FOR ADAPTATION TO MEET SITUATIONAL CONDITIONS. THE TEACHING UNITS ARE GROUPED UNDER THE GENERAL TOPIC HEADINGS OF(1) ELEMENTS OF MUSIC,(2) THE SCIENCE OF SOUND,(3) MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS,(4) AMERICAN FOLK MUSIC, (5) MUSIC IN NEW YORK STATE,(6) MUSIC OF THE THEATER,(7) MUSIC FOR INSTRUMENTAL GROUPS,(8) OPERA,(9) MUSIC OF OTHER CULTURES, AND (10) HISTORICAL PERIODS IN MUSIC. THE PRESENTATION OF EACH UNIT CONSISTS OF SUGGESTIONS FOR (1) SETTING THE STAGE' (2) INTRODUCTORY DISCUSSION,(3) INITIAL MUSICAL EXPERIENCES,(4) DISCUSSION AND DEMONSTRATION, (5) APPLICATION OF SKILLS AND UNDERSTANDINGS,(6) RELATED PUPIL ACTIVITIES, AND(7) CULMINATING CLASS ACTIVITY (WHERE APPROPRIATE). SUITABLE PERFORMANCE LITERATURE, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE CITED FOR USE WITH EACH OF THE UNITS. SEVEN EXTENSIVE BE.LIOGRAPHIES ARE INCLUDED' AND SOURCES OF BIBLIOGRAPHICAL ENTRIES, RECORDINGS, AND FILMS ARE LISTED. (JS) ,; \\',,N.k-*:V:.`.$',,N,':;:''-,",.;,1,4 / , .; s" r . ....,,'IA, '','''N,-'0%')',", ' '4' ,,?.',At.: \.,:,, - ',,,' :.'v.'',A''''',:'- :*,''''.:':1;,- s - 0,- - 41tl,-''''s"-,-N 'Ai -OeC...1%.3k.±..... -,'rik,,I.k4,-.&,- ,',V,,kW...4- ,ILt'," s','.:- ,..' 0,4'',A;:`,..,""k --'' .',''.- '' ''-. -

Adapting Traditional Kentucky Thumbpicking Repertoire for the Classical Guitar

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2015 Adapting Traditional Kentucky Thumbpicking Repertoire for the Classical Guitar Andrew Rhinehart University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Rhinehart, Andrew, "Adapting Traditional Kentucky Thumbpicking Repertoire for the Classical Guitar" (2015). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 44. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/44 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

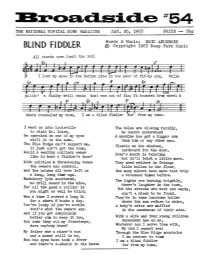

BLIND FIDDLER © Copyright 1965 Deep Fork Husic

c:l.si THE NATIONAL TOPICAL SONG MAGAZINE JAN. 20, 1965 PRICE -- 50¢ Words & Music: ERIC ANDERSEN BLIND FIDDLER © Copyright 1965 Deep Fork Husic All chords open (omit the 3rd) there concealed my doom, I am a blind fiddler . ar from my home. I went up into Louisville The holes are closing rapidly, to visit Dr. Laine, he cannot understand He operated on one of my eyes A machine has got a bigger arm still it is the same. than him or ~ other man. The Blue Ridge can't support me, Plastic on the ,windows, it just ain't got the room, cardboard for the door, Would a wealthy colliery owner Baby's mouth is twisting like to hear a fiddler's tune? but it'll twist a little more. With politics & threatening tones They need welders in Chicago the owners can control, falls hollow to the floor, And the unions all have left us How many miners have made that trip a long, long time ago. a thousand times before. Machinery ~in scattered, The lights are burning brightly, nCOJ drill sound in the mine, there's laughter in the town, For all the good a collier is But the streets are dark and empty, you might as well be blind. ain I t a miner to be found. Was a time I worked a long 14 They're in some lonesome holler for a short 8 bucks a day. where the sun refuse to shine, You I re lucky if you're workin A baby's cries are muffled that's what the owners say. -

Creating a Roadmap for the Future of Music at the Smithsonian

Creating a Roadmap for the Future of Music at the Smithsonian A summary of the main discussion points generated at a two-day conference organized by the Smithsonian Music group, a pan- Institutional committee, with the support of Grand Challenges Consortia Level One funding June 2012 Produced by the Office of Policy and Analysis (OP&A) Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Background ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Conference Participants ..................................................................................................................... 5 Report Structure and Other Conference Records ............................................................................ 7 Key Takeaway ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Smithsonian Music: Locus of Leadership and an Integrated Approach .............................. 8 Conference Proceedings ...................................................................................................................... 10 Remarks from SI Leadership ........................................................................................................ -

The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography

LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations William H. Hannon Library 8-2014 The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography Jeffrey Gatten Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/librarian_pubs Part of the Music Commons Repository Citation Gatten, Jeffrey, "The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography" (2014). LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations. 91. https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/librarian_pubs/91 This Article - On Campus Only is brought to you for free and open access by the William H. Hannon Library at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in LMU Librarian Publications & Presentations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Popular Music and Society, 2014 Vol. 37, No. 4, 464–475, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2013.834749 The Woody Guthrie Centennial Bibliography Jeffrey N. Gatten This bibliography updates two extensive works designed to include comprehensively all significant works by and about Woody Guthrie. Richard A. Reuss published A Woody Guthrie Bibliography, 1912–1967 in 1968 and Jeffrey N. Gatten’s article “Woody Guthrie: A Bibliographic Update, 1968–1986” appeared in 1988. With this current article, researchers need only utilize these three bibliographies to identify all English- language items of relevance related to, or written by, Guthrie. Introduction Woodrow Wilson Guthrie (1912–67) was a singer, musician, composer, author, artist, radio personality, columnist, activist, and philosopher. By now, most anyone with interest knows the shorthand version of his biography: refugee from the Oklahoma dust bowl, California radio show performer, New York City socialist, musical documentarian of the Northwest, merchant marine, and finally decline and death from Huntington’s chorea. -

Interstellar Music - by Mike Overly

Interstellar Music - by Mike Overly Let's imagine that you could toss a message in a bottle faster than a speeding bullet into the cosmic ocean of outer space. What would you seal inside it for anyone, or anything, to open some day in the distant future, in a galaxy far, far away from our solar system? Well, imagine no more because it's been done! Thirty-five years ago, NASA launched two Voyager spacecraft carrying earthly images and sounds toward the Stars. Voyager 1 was launched on September 5, 1977, from Cape Canaveral, Florida and Voyager 2 was sent on its way August 20 of that same year. Voyager 1 is now 11 billion miles away from earth and is the most distant of all human-made objects. Everyday, it flies another million miles farther. In fact, Voyager 1 and 2 are so far out in space that their radio signals, traveling at the speed of light, take 16 hours to reach Earth. These radio signals are captured daily by the big dish antennas of the Deep Space Network and arrive at a strength of less than one femtowatt, a millionth of a billionth of a watt. Wow! Both Voyagers are headed towards the outer boundary of the solar system, known as the heliopause. This is the region where the Sun's influence wanes and interstellar space waxes. Also, the heliopause is where the million-mile-per-hour solar winds slow down to about 250,000 miles per hour. The Voyagers have reached these solar winds, also known as termination shock, and should cross the heliopause in another 10 to 20 years. -

Theo Bikel with Pete Seeger (And More)

Theo Bikel with Pete Seeger (and more) First, here’s another item for consideration by people who think that Pete Seeger was anti-Israel. (If you haven’t already, read Hillel Schenker’s recent post on this.) We have the permission of Gerry Magnes — active with the Albany, NY regional J Street chapter, who married into an Israeli family — to quote what he emailed the other day: Thought I would share a small anecdote my father in law once told me. He’s 95 and still living on a kibbutz (Kibbutz Evron) in the Western Galilee. Last winter, when my wife and I mentioned to him that we’d just attended a Pete Seeger concert . in Schenectady, . he related how he’d seen him perform (I think in Tel Aviv), probably in ’64. When he [Seeger] began to speak about the Israeli-Palestinian/Arab conflict at that time and his hopes for peace, he began to cry. He had to stop talking or singing for a bit until he could collect himself. The sincerity and depth of feeling left a deep impression on my father in law. http://www.cookephoto.com/dylanovercome.html Partners’ board chair Theodore Bikel goes back a long way with Seeger. They were part of the original board (with Oscar Brand, George Wein and Albert Grossman) that founded the Newport Folk Festival. This image captures a festival high point in 1963, with Theo and Seeger (at right) joining Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, the Freedom Singers and Peter, Paul and Mary to sing “We Shall Overcome.” Here’s Theo singing Hine Ma Tov with Seeger and Rashid Hussain (the latter identified as a Palestinian poet) from episode 29 of the 39-episode run of the “Rainbow Quest” UHF television series (1965-66), dedicated to folk music and hosted by Seeger: Upon hearing of Seeger’s passing, Theo wrote this on his Facebook page: An era has come to an end. -

![Kurt Schwitters's Merzbau: Chaos, Compulsion and Creativity Author[S]: Clare O’Dowd Source: Moveabletype, Vol](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6290/kurt-schwitterss-merzbau-chaos-compulsion-and-creativity-author-s-clare-o-dowd-source-moveabletype-vol-696290.webp)

Kurt Schwitters's Merzbau: Chaos, Compulsion and Creativity Author[S]: Clare O’Dowd Source: Moveabletype, Vol

Article: Kurt Schwitters's Merzbau: Chaos, Compulsion and Creativity Author[s]: Clare O’Dowd Source: MoveableType, Vol. 5, ‘Mess’ (2009) DOI: 10.14324/111.1755-4527.046 MoveableType is a Graduate, Peer-Reviewed Journal based in the Department of English at UCL. © 2009 Clare O’Dowd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) 4.0https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Moveable Type Vol. 5 2009: CLARE O’DOWD 1 Kurt Schwitters' Merzbau : Chaos, Compulsion and Creativity For nearly thirty years until his death in 1948, the German artist Kurt Schwitters constructed environments for himself: self-contained worlds, places of safety, nests. Everywhere he went he stockpiled materials and built them into three-dimensional, sculptural edifices. By the time he left Hanover in 1937, heading for exile in England, Schwitters, his wife, his son, his parents, their lodgers, and a large number of guinea pigs had all been living in the midst of an enormous, detritus-filled sculpture that had slowly engulfed large parts of their home for almost twenty years. 1 Schwitters was by no means the only artist to have a cluttered studio, or to collect materials for his work. So the question must be asked, what was it about Schwitters’ activities that was so unusual? How can these and other aspects of his work and behaviour be considered to go beyond what might be regarded as normal for an artist working at that time? And more importantly, what were the reasons for this behaviour? In this paper, I will examine the beginnings of the Merzbau , the architectural sculpture that Schwitters created in his Hanover home. -

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986

Moses and Frances Asch Collection, 1926-1986 Cecilia Peterson, Greg Adams, Jeff Place, Stephanie Smith, Meghan Mullins, Clara Hines, Bianca Couture 2014 Ralph Rinzler Folklife Archives and Collections Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage 600 Maryland Ave SW Washington, D.C. [email protected] https://www.folklife.si.edu/archive/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement note............................................................................................................ 3 Biographical/Historical note.............................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Correspondence, 1942-1987 (bulk 1947-1987)........................................ 5 Series 2: Folkways Production, 1946-1987 (bulk 1950-1983).............................. 152 Series 3: Business Records, 1940-1987.............................................................. 477 Series 4: Woody Guthrie