Protean Madness and the Poetic Identities of Smart, Cowper, and Blake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caribbean Appeals Appeals by Colony

CARIBBEAN APPEALS including Antigua, Bahamas, Barbados, Bermuda, Dominica, East Florida, Grenada, Guiana, Jamaica, Leeward Islands, Montserrat, Nevis, St. Christopher, St. Vincent, Tobago, Tortola, West Florida This preliminary list of appeals was constructed from index entries in the Acts of the Privy Council, Colonial Series (APC), beginning with the year 1674 and ending with 1783. The focus is on appeals or petitions for leave to appeal with a definite lower court decision. A list by colony and section number of matters indexed as appeals but for which no lower court decision is apparent is provided for each volume of the APC. A smattering of disputes, not indexed as appeals (and so noted in this list), are included if the APC abstract uses appeals language. Prize cases are not included if the matter was referred to the Committee for Hearing Appeals on Prize. Appeals are listed according to the location in the margin note unless otherwise explained. The spelling of the names of parties is accepted as presented in the APC abstracts. Appeals with John Doe or Richard Roe as named parties are treated as if those parties were individuals. Significant doubt about the identity of the respondent(s) results in the designation ‘X, appeal of” as the name of the case. Given the abbreviated nature of the abstracts, additional research in the Privy Council registers, in genealogical records, and on matters of procedure will be needed to clarify the case names throughout and establish their accuracy. If the APC only uses wording such as “petition of John Jones referred,” the action was not assumed to be an appeal. -

Standard Resolution 19MB

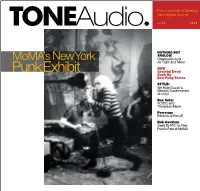

The e-journal of analog and digital sound. no.24 2009 NOTHING BUT ANALOG! MoMA’s New York Clearaudio, Lyra, Air Tight and More NEW Punk Exhibit Grateful Dead Book By Ben Fong-Torres STYLE: We Ride Ducati’s Newest Supermotard At Indy! Box Sets: AC/DC and Thelonius Monk Perreaux Returns to the US Bob Gendron Goes To NYC to View Punk’s Past at MoMA TONE A 1 NO.24 2 0 0 9 PUBLISHER Jeff Dorgay EDITOR Bob Golfen ART DIRECTOR Jean Dorgay r MUSIC EDITOR Ben Fong-Torres ASSISTANT Bob Gendron MUSIC EDITOR M USIC VISIONARY Terry Currier STYLE EDITOR Scott Tetzlaff C O N T R I B U T I N G Tom Caselli WRITERS Kurt Doslu Anne Farnsworth Joe Golfen Jesse Hamlin Rich Kent Ken Kessler Hood McTiernan Rick Moore Jerold O’Brien Michele Rundgren Todd Sageser Richard Simmons Jaan Uhelszki Randy Wells UBER CARTOONIST Liza Donnelly ADVERTISING Jeff Dorgay WEBSITE bloodymonster.com Cover Photo: Blondie, CBGB’s. 1977. Photograph by Godlis, Courtesy Museum of Modern Art Library tonepublications.com Editor Questions and Comments: [email protected] 800.432.4569 © 2009 Tone MAGAZIne, LLC All rights reserved. TONE A 2 NO.24 2 0 0 9 55 (on the cover) MoMA’s Punk Exhibit features Old School: 1 0 The Audio Research SP-9 By Kurt Doslu Journeyman Audiophile: 1 4 Moving Up The Cartridge Food Chain By Jeff Dorgay The Grateful Dead: 29 The Sound & The Songs By Ben Fong-Torres A BLE Home Is Where The TURNta 49 FOR Record Player Is EVERYONE By Jeff Dorgay Here Today, Gone Tomorrow: 55 MoMA’s New York Punk Exhibit By Bob Gendron Budget Gear: 89 How Much Analog Magic Can You Get for Under $100? By Jerold O’Brien by Ben Fong-Torres, published by Chronicle Books 7. -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

The Gentleman's Magazine; Or Speakers’ Corner 105

Siegener Periodicum zur Internationalen Empirischen______ Literaturwissenschaft Herausgegeben von Reinhold Viehoff (Halle/Saale) Gebhard Rusch (Siegen) Rien T. Segers (Groningen) Jg. 19 (2000), Heft 1 Peter Lang Europäischer Verlag der Wissenschaften SPIEL Siegener Periodicum zur Internationalen Empirischen Literaturwissenschaft SPIEL: Siegener Periodicum zur Internationalen Empirischen Literaturwissenschaft Jg. 19 (2000), Heft 1 Peter Lang Frankfurt am Main • Berlin • Bern • Bruxelles • New York • Oxford • Wien Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Siegener Periodicum zur internationalen empirischen Literatur wissenschaft (SPIEL) Frankfurt am Main ; Berlin ; Bern ; New York ; Paris ; Wien : Lang ISSN 2199-80780722-7833 Erscheint jährl. zweimal JG. 1, H. 1 (1982) - [Erscheint: Oktober 1982] NE: SPIEL ISSNISSN 2199-80780722-7833 © Peter Lang GmbH Europäischer Verlag der Wissenschaften Frankfurt am Main 2001 Alle Rechte Vorbehalten. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages unzulässig und strafbar. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Verarbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. Siegener Periodicum zur Internationalen Empirischen Literaturwissenschaft SPECIAL ISSUE / SONDERHEFT SPIEL 19 (2000), H. 1 Historical Readers and Historical Reading Historische Leser und historisches Lesen ed. by / hrsg. von Margaret Beetham (Manchester) & -

Quarterly Rev Ie W

' ' " ' ' ; ; ; . : .. , . THE ; '¦': . ' EREEMASONS' . V. V QUARTERLY REV IE W. SECOND SERIES—DECEMBER 31,- 1846. r * I have ever fel t it my duty to support and encourage its princi ples and practice, .because it powerfully developes all social and benevolent affections; because it mitigates without, and annihilates within , tbe virulence of politieal and theolngieal eontroversyr^heeause.it affords the only neutral ground on which all ranks and classes can meet in perfect equality, and associate without degradation or mortification, whether for purposes of moral instruction or social intercourse.'*—T/ie EAUL OV DURHAM on Freemasonry, 21st Jan.'1834. ' ¦ '.yy: ". This obedience, which must be vigorously observed, does not prevent us, howeVer rfrom investigating the inconvenience of laws, which at the time they were framed may have.been political, prudent—nay, even necessary ; but now, from a total change of circumstances"and ' ¦ events, may have become unjust, oppressive, and equally useless. *' *.- ., '.* " -: "Justinian declares that he acts contrary to tbe law who, confining himself to the letter, acts.contrary to the spirit and interest of it."—H. R.H. the D UKE OF S USSEX, April 21. 1812. House of Lords. AT the Quarterly Communication of the United Grand Lodge of England, held in September last, the Grand Secretary announced that in the event of the confirmation of the minutes of the previous Grand Lodge held in June, he had authority to read, if required, a letter which the Gran d Master the Earl of Zetland intended to transmit to the Grand Master of Berlin, in relation to the non-admission of any Brethren to Lodges under that Masonic authority excepting such as professed the Christian, faith. -

A Hermeneutics of Contemplative Silence: Paul Ricoeur and the Heart of Meaning Michele Therese Kueter Petersen University of Iowa

University of Iowa Iowa Research Online Theses and Dissertations 2011 A hermeneutics of contemplative silence: Paul Ricoeur and the heart of meaning Michele Therese Kueter Petersen University of Iowa Copyright 2011 Michele Therese Kueter Petersen This dissertation is available at Iowa Research Online: http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/1494 Recommended Citation Petersen, Michele Therese Kueter. "A hermeneutics of contemplative silence: Paul Ricoeur and the heart of meaning." PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) thesis, University of Iowa, 2011. http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/1494. Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd Part of the Religion Commons A HERMENEUTICS OF CONTEMPLATIVE SILENCE: PAUL RICOEUR AND THE HEART OF MEANING by Michele Therese Kueter Petersen An Abstract Of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in Religious Studies in the Graduate College of The University of Iowa 1 December 2011 Thesis Supervisor: Professor David E. Klemm 1 ABSTRACT The practice of contemplative silence, in its manifestation as a mode of capable being, is a self-consciously spiritual and ethical activity that aims at a transformation of reflexive consciousness. I assert that contemplative silence manifests a mode of capable being in which we have an awareness of the awareness of the awareness of being with being whereby we can constitute and create a shared world of meaning(s) through poetically presencing our being as being with others. The doubling and tripling of the term "awareness" refers to five contextual levels of awareness, which are analyzed, including immediate self-awareness, immediate objective awareness, reflective awareness, reflexive awareness, and contemplative awareness. -

Ballad Opera in England: Its Songs, Contributors, and Influence

BALLAD OPERA IN ENGLAND: ITS SONGS, CONTRIBUTORS, AND INFLUENCE Julie Bumpus A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 7, 2010 Committee: Vincent Corrigan, Advisor Mary Natvig ii ABSTRACT Vincent Corrigan, Advisor The ballad opera was a popular genre of stage entertainment in England that flourished roughly from 1728 (beginning with John Gay's The Beggar's Opera) to 1760. Gay's original intention for the genre was to satirize not only the upper crust of British society, but also to mock the “excesses” of Italian opera, which had slowly been infiltrating the concert life of Britain. The Beggar's Opera and its successors were to be the answer to foreign opera on British soil: a truly nationalistic genre that essentially was a play (building on a long-standing tradition of English drama) with popular music interspersed throughout. My thesis explores the ways in which ballad operas were constructed, what meanings the songs may have held for playwrights and audiences, and what influence the genre had in England and abroad. The thesis begins with a general survey of the origins of ballad opera, covering theater music during the Commonwealth, Restoration theatre, the influence of Italian Opera in England, and The Beggar’s Opera. Next is a section on the playwrights and composers of ballad opera. The playwrights discussed are John Gay, Henry Fielding, and Colley Cibber. Purcell and Handel are used as examples of composers of source material and Mr. Seedo and Pepusch as composers and arrangers of ballad opera music. -

Ec-1000 Ec-1000 / M-1000

JAKE E LEE TOMI KOIVUSAARI CHRIS GARZA ALEX DEROSSO LUKE Kilpatrick ROB holliday DIEGO VERDUZCO BAZIE CRAIG GOLDY DeLuxe Amorphis Suicide Silence Parkway Drive Marilyn Manson, Prodigy Ill Niño The 69 Eyes Dio SERIES SPECIFICATIONS ec-1000fr ec-1000fm ec-1000fm w/Duncans ec-1000Qm SPECIFICATIONS ec-1000 BLK ec-1000 SW ec-1000 VB m-1000 m-1000fm CONSTRUCTION / SCALE Set-Neck / 24.75” Set-Neck / 24.75” Set-Neck / 24.75” Set-Neck / 24.75” CONSTRUCTION / SCALE Set-Neck / 24.75” Mahogany Set-Neck / 24.75” Set-Neck / 24.75” Set-Thru / 25.5” Set-Thru / 25.5” BODY Mahogany w/ Flamed Maple Top Mahogany w/ Flamed Maple Top Mahogany w/ Flamed Maple Top Mahogany w/ Quilted Maple Top BODY Mahogany Mahogany Mahogany Alder Alder w/ Flamed Maple Top NECK / FINGERBOARD Mahogany / Rosewood Mahogany / Rosewood Mahogany / Rosewood Mahogany / Rosewood NECK / FINGERBOARD Mahogany / Rosewood Mahogany / Rosewood Mahogany / Ebony Maple / Rosewood Maple / Rosewood NUT 42mm Locking 42mm Earvana Compensated 42mm Earvana Compensated 42mm Earvana Compensated NUT 42mm Earvana Compensated 42mm Earvana Compensated 42mm Earvana Compensated 43mm Locking 43mm Locking NECK CONTOUR Thin U Thin U Thin U Thin U NECK CONTOUR Thin U Thin U Thin U Extra Thin U Extra Thin U FRETS 24 XJ 24 XJ 24 XJ 24 XJ FRETS 24 XJ 24 XJ 24 XJ 24 XJ 24 XJ HARDWARE Black Nickel Black Nickel Chrome Black Nickel HARDWARE Gold Black Nickel Gold Black Nickel Black Nickel TUNERS ESP ESP Locking ESP Locking ESP Locking TUNERS ESP Locking ESP Locking ESP Locking Grover Grover BRIDGE Floyd Rose 1000 Series -

Jerry Cantrell Jerry Cantrell

Jerry Cantrell Jerry Cantrell - vocals / guitar Robert Trujillo - bass Mike Bordin - drums From the lyrically and sonically mournful “Psychotic Break” to when the mental and musical exorcism of Jerry Cantrell's nearly 73-minute aural Degradation Trip concludes with the lovely, somnolent, bluesy strains of “Gone,” the singer/guitarist's Roadrunner debut is a sundry and sometimes scary journey to the center of a psyche. It may not always be a pretty trip, but it's a close-to-the-bone excursion that haunts both its creator and its listeners. As the multi-faceted artist relates, “In '98, I locked myself in my house, went out of my mind and wrote 25 songs,” says the then-fully-bearded Cantrell. “I rarely bathed during that period of writing; I sent out for food, I didn't really venture out of my house in three or four months. It was a hell of an experience. The album is an overview of birth to now. That's all,” he grins, though the visceral and haunting songs, by turns soaring and raw, do reflect that often-naked and sometimes-grim truth. “Boggy Depot [his 1998 solo bow] is like Kindergarten compared to this,” he furthers. “The massive sonic growth from Boggy Depot to Degradation Trip is comparable to the difference between our work in the Alice In Chains albums Facelift to Dirt, which was also a tremendous leap.” And all of Cantrell's 25 prolifically penned songs will see the light of day by 2003. Degradation Trip, which will be released June 18, is comprised of 14 songs from the personal, transcendent writing marathon that inspired such self-searching cuts as “Bargain Basement Howard Hughes,” “Hellbound,” and “Profalse Idol.” The second batch of songs—“as sad and brutal as Degradation Trip” —Cantrell promises, are due out on Roadrunner 2003. -

The Romance of London

1 If I UA-^fefJutwc^? *1 * ytyeyfl Jf'UW^ iMKW»**tflff*ewi r CONTENTS. SUPERNATURAL STORIES. PAGB GHOST STORY EXPLAINED, .... I ["EPNEY LEGEND OF THE FISH AND THE. RING, 4 'REAM TESTIMONY, ..... 6 IARYLEBONE FANATICS : SHARP AND BRYAN, BROTHERS AND SOUTHCOTE, ..... 7 iALLUCINATION IN ST PAUL'S, .... H THE GHOST IN THE TOWER, ..... 18 TGHTS AND SHOWS, AND PUBLIC AMUSEMENTS. THE PUISNE'S WALKE ABOUT LONDON, 27 THE WALLS OF ROMAN LONDON, 30 THE DANES IN LONDON, 32 CITY REGULATIONS IN THE PLANTAGENET TIMES, 36 ST PAUL'S DAY IN LONDON, 37 CHRISTMAS FESTIVITIES IN WESTMINSTER HALL, 39 LONDON COCKPITS, .... 43 STORY OF THE BOOK OF ST ALBAN'S, 45 RACES IN HYDE PARK. 47 VI Contents. PAGK OLD PALL MALL SIGHTS, 49 ROMANCE OF SCHOMBERG HOUSE, . 5° DR GRAHAM AND HIS QUACKERIES, . 54 ORIGIN OF HACKNEY-COACHES, Co THE PARISH CLERKS OF CLERKENWELL, 62 SEDAN-CHAIRS IN LONDON, 62 A LONDON NEWSPAPER OF 1 667, 65 AMBASSADORS' SQUABBLE, . 67 DRYDEN CUDGELLED, 69 FUNERAL OF DRYDEN, 7i GAMING-HOUSES KEPT BY LADIES, . 73 ROYAL GAMING AT CHRISTMAS, 75 PUNCH AND JUDY, 77 FANTOCCINI, 81 MRS SALMON'S WAX-WORK, . 33 THE RAGGED REGIMENT IN WESTMINSTER ABBEY, 86 THE PIG-FACED LADY, 89 COUNT BORUWLASKI AND GEORGE IV., 92 THE IRISH GIANTS, . 95 A NORFOLK GIANT, . 99 CELEBRATED DWARFS, 100 PLAYING ON THE SALT-BOX, . 103 A SHARK STORY, 104 TOPHAM, THE STRONG MAN OF ISLINGTON, 105 THE POPE'S PROCESSION, AND BURNING OF THE TOPE, 107 THE GIANTS AT GUILDHALL, "5 120 LORD MAYOR'S DAY, .... PRESENTATION OF SHERIFFS, i-4 LORD MAYOR'S FOOL, 125 KING GEORGE III. -

Your Recreation Center

Archives LD729.6 C5 075 Ol~ion. vol. 46 no. 6 1::'.:1 0 1 2001 Feb. 28, 2(2)(2)1 rc" I Meriam Library--CSU Chico ',.~"; U , "-.-IrurlLll!CO b 2001 IUatiollal NCWSIHiPElI' of tile Veal' WEDNESDAY FEBRUARY 28, 2001 .1 .IN'SIDE ~ OPINION, A8 ~ SPORTS, 61 (( Once someone went around and pOllred lESS ~S MORE ',. ENTERTAINMENT, C1 Ska band Less Than Jal<e antifreeze on thejood we use to catch ~ CALENDAR, C6 sprints to The Brick Works JJ ~. COMICS, C'l the cats. - KATHY HAI.LOItAN, CHICO C/I'!' CCltIl.l'rION ~ CLASSIFIEDS, C9 oI MEN SID N S ~ D5 ENTERTAINMENT ~C1 ;':'-:- "......... -.1 Jo.. DIMENSIONS, D1 Volume 46, Issue 6 CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, C H I C 0 http://orion.csuchico.cdu \!iiIiji.sre'--T·-rjjfijj'itij¥ijiik~"!!H· , U' "¥ ~'Eiiii4filMjf"'''''''_'-'''iC YOUR RECREATION CENTER YES THE CHOICE IS YOURS MARCH 7 AND 8 NO Brought to you by the leHer '0' Weary and a little rumpled, Rec center seven members of The Orion staff returned to Chico Sunday - from four days in San Francisco. We took our trip to the city in an debates oversized blue van that evoked memories of summer camps and family road trips. Rambling get sweaty down Interstate 5 also reminded some of us how uncomfortable three hours in a van can be. CAROLYN MARIE LUCAS Nonetheless, upon our return, STAFF \'l/RITEI< our blood-shot eyes sparkled with sa~sfactiolJ. The Orion was named oeal health club owners are feeling National Newspaper of the Year Lthe burn. in the four-year college weekly Within the last few days, the owners category at the National College of eight different health clubs have --..: Newspaper Convention. -

Volume 5 November, 1967 Number J Front Cover

RHODE ISLAND JEWISH HISTORICAL NOTES VOLUME 5 NOVEMBER, 1967 NUMBER J FRONT COVER DAVID CHARAK ADELMAN Founder of the Rhode Island Jewish Historical Association See page 3. RHODE ISLAND JEWISH HISTORICAL VOLUME 5, NUMBER 1 NOVEMBER, 1967 Copyright November, 1967 by the RHODE ISLAND JEWISH HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 209 ANGELL STREET, PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND 02906 RHODE ISLAND JEWISH HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 209 ANGELL STREET, PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND TABLE OF CONTENTS DAVID CHARAK ADELMAN Front Cover NEW PROVIDENCE CONSERVATIVE SYNAGOGUE 1921 .... Back Cover DAVID CHARAK ADELMAN 3 A CATALOGUE OF ALL RHODE ISLAND JEWS MENTIONED IN MATERIALS RELATING TO RHODE ISLAND JEWS IN RHODE ISLAND DEPOSITORIES 1678-1966 7 Compiled and Edited by Freda Egnal BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES 79 Compiled by Gertrude Nisson Goldowsky THE PROVIDENCE CONSERVATIVE SYNAGOGUE—TEMPLE BETH-ISRAEL ... 81 by Benton Rosen HYMAN B. LASKER 1868-1938 I. AN APPRECIATION 101 by Beryl Segal II. MEMOIR 107 by Rabbi Meir Lasker HOME OF THE CONGREGATION OF THE SONS OF ISRAEL AND DAVID 1877-1883 . 119 WE LOOK BACK 120 by Rabbi William G. Braude THIRTEENTH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE ASSOCIATION 127 NECROLOGY 129 EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OFFICERS OF THE ASSOCIATION DAVID C. ADELMAN* Honorary President BERNARD SEGAL . President JEROME B. SPUNT . Vice President MRS. SEEBERT J. GOLDOWSKY . Secretary MRS. LOUIS I. SWEET . Treasurer *Deceased MEMBERS-AT-LARGE OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE RABBI WILLIAM G. BRAUDE WILLIAM B. ROBIN SEEBERT J. GOLDOWSKY, M. D. ERWIN STRASMICH SIDNEY GOLDSTEIN LOUIS I. SWEET MRS. CHARLES POTTER MELVIN L. ZURIER SEEBERT JAY GOLDOWSKY, M. D., Editor Miss DOROTHY M. ABBOTT, Librarian Printed in the U. S.