Hobbes and Spinoza

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Standard Resolution 19MB

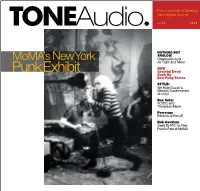

The e-journal of analog and digital sound. no.24 2009 NOTHING BUT ANALOG! MoMA’s New York Clearaudio, Lyra, Air Tight and More NEW Punk Exhibit Grateful Dead Book By Ben Fong-Torres STYLE: We Ride Ducati’s Newest Supermotard At Indy! Box Sets: AC/DC and Thelonius Monk Perreaux Returns to the US Bob Gendron Goes To NYC to View Punk’s Past at MoMA TONE A 1 NO.24 2 0 0 9 PUBLISHER Jeff Dorgay EDITOR Bob Golfen ART DIRECTOR Jean Dorgay r MUSIC EDITOR Ben Fong-Torres ASSISTANT Bob Gendron MUSIC EDITOR M USIC VISIONARY Terry Currier STYLE EDITOR Scott Tetzlaff C O N T R I B U T I N G Tom Caselli WRITERS Kurt Doslu Anne Farnsworth Joe Golfen Jesse Hamlin Rich Kent Ken Kessler Hood McTiernan Rick Moore Jerold O’Brien Michele Rundgren Todd Sageser Richard Simmons Jaan Uhelszki Randy Wells UBER CARTOONIST Liza Donnelly ADVERTISING Jeff Dorgay WEBSITE bloodymonster.com Cover Photo: Blondie, CBGB’s. 1977. Photograph by Godlis, Courtesy Museum of Modern Art Library tonepublications.com Editor Questions and Comments: [email protected] 800.432.4569 © 2009 Tone MAGAZIne, LLC All rights reserved. TONE A 2 NO.24 2 0 0 9 55 (on the cover) MoMA’s Punk Exhibit features Old School: 1 0 The Audio Research SP-9 By Kurt Doslu Journeyman Audiophile: 1 4 Moving Up The Cartridge Food Chain By Jeff Dorgay The Grateful Dead: 29 The Sound & The Songs By Ben Fong-Torres A BLE Home Is Where The TURNta 49 FOR Record Player Is EVERYONE By Jeff Dorgay Here Today, Gone Tomorrow: 55 MoMA’s New York Punk Exhibit By Bob Gendron Budget Gear: 89 How Much Analog Magic Can You Get for Under $100? By Jerold O’Brien by Ben Fong-Torres, published by Chronicle Books 7. -

Philosophy of Natural Law

4YFPMWLIHMR-RWXMXYXI W.SYVREP7IT PHILOSOPHY OF NATURAL LAW Justice K. N. Saikia Former Judge Supreme Court of India. Director General National Judicial Academy By philosophy of law, for the purpose of this article, is meant the pursuit of wisdom, truth and knowledge of law by use of reason. In other words, philosophy of law means the ratlonal investigation and study of the basic ideal and principles of law. The philosophy of natural law is the subject of this article. Longing for a Higher Law - In the human bosom there has always been a longing for a higher law than those made by the community itself. The divine theory of law, the theory of natural law, and the principles of natural justice are some theories or notions found in fulfilment of this longing. Divine laws are those ascribed to God. Divine rights of kings were supposed to have been derived from God. Laws which are claimed to be God-made, may not be amendable by man; and their reasoning and provisions also not to be ques- tioned by man. Greek thinkers from Homer to the Stoics, and reflections of Plato and Aristotle mainly provide the beginning of systematic legal thinking. In Homer, law is embodied in the themistes which the kings receive from Zeus as the divine source of all earthly justice which is still identical with order and authority. Solon the great Athenian lawgiver appeals to Dike, the daughter of Zeus, as a guarantor of justice against earthly tyranny, violation of rights and social injustice. The Code of Hamurapi was handed over by the Sun god. -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

Catholicism and the Natural Law: a Response to Four Misunderstandings

religions Article Catholicism and the Natural Law: A Response to Four Misunderstandings Francis J. Beckwith Department of Philosophy, Baylor University, Waco, TX 76710, USA; [email protected] Abstract: This article responds to four criticisms of the Catholic view of natural law: (1) it commits the naturalistic fallacy, (2) it makes divine revelation unnecessary, (3) it implausibly claims to establish a shared universal set of moral beliefs, and (4) it disregards the noetic effects of sin. Relying largely on the Church’s most important theologian on the natural law, St. Thomas Aquinas, the author argues that each criticism rests on a misunderstanding of the Catholic view. To accomplish this end, the author first introduces the reader to the natural law by way of an illustration he calls the “the ten (bogus) rules.” He then presents Aquinas’ primary precepts of the natural law and shows how our rejection of the ten bogus rules ultimately relies on these precepts (and inferences from them). In the second half of the article, he responds directly to each of the four criticisms. Keywords: Catholicism; natural law theory; Aquinas; naturalistic fallacy The purpose of this article is to respond to several misunderstandings of the Catholic view of the natural law. I begin with a brief account of the natural law, relying primarily on the work of St. Thomas Aquinas, the Church’s most important theologian on this subject. Citation: Beckwith, Francis J.. 2021. I then move on and offer replies to four criticisms of the natural law that I argue rest on Catholicism and the Natural Law: A misunderstandings: (1) the natural law commits the so-called “naturalistic fallacy,” (2) the Response to Four Misunderstandings. -

The Teachings of Confucius: a Basis and Justification for Alternative Non-Military Civilian Service

THE TEACHINGS OF CONFUCIUS: A BASIS AND JUSTIFICATION FOR ALTERNATIVE NON-MILITARY CIVILIAN SERVICE Carolyn R. Wah* Over the centuries the teachings of Confucius have been quoted and misquoted to support a wide variety of opinions and social programs ranging from the suppression and sale of women to the concerted suicide of government ministers discontented with the incoming dynasty. Confucius’s critics have asserted that his teachings encourage passivity and adherence to rites with repression of individuality and independent thinking.1 The case is not that simple. A careful review of Confucius’s expressions as preserved by Mencius, his student, and the expressions of those who have studied his teachings, suggests that Confucius might have found many of the expressions and opinions attributed to him to be objectionable and inconsistent with his stated opinions. In part, this misunderstanding of Confucius and his position on individuality, and the individual’s right to take a stand in opposition to legitimate authority, results from a distortion of two Confucian principles; namely, the principle of legitimacy of virtue, suggesting that the most virtuous man should rule, and the principle of using the past to teach the present.2 Certainly, even casual study reveals that Confucius sought political stability, but he did not discourage individuality or independent *She is associate general counsel for Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania. She received her J.D. from Rutgers University Law School and B.A. from The State University of New York at Oswego. She has recently received her M.A. in liberal studies with an emphasis on Chinese studies from The State University of New York—Empire State College. -

A Hermeneutics of Contemplative Silence: Paul Ricoeur and the Heart of Meaning Michele Therese Kueter Petersen University of Iowa

University of Iowa Iowa Research Online Theses and Dissertations 2011 A hermeneutics of contemplative silence: Paul Ricoeur and the heart of meaning Michele Therese Kueter Petersen University of Iowa Copyright 2011 Michele Therese Kueter Petersen This dissertation is available at Iowa Research Online: http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/1494 Recommended Citation Petersen, Michele Therese Kueter. "A hermeneutics of contemplative silence: Paul Ricoeur and the heart of meaning." PhD (Doctor of Philosophy) thesis, University of Iowa, 2011. http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/1494. Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd Part of the Religion Commons A HERMENEUTICS OF CONTEMPLATIVE SILENCE: PAUL RICOEUR AND THE HEART OF MEANING by Michele Therese Kueter Petersen An Abstract Of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in Religious Studies in the Graduate College of The University of Iowa 1 December 2011 Thesis Supervisor: Professor David E. Klemm 1 ABSTRACT The practice of contemplative silence, in its manifestation as a mode of capable being, is a self-consciously spiritual and ethical activity that aims at a transformation of reflexive consciousness. I assert that contemplative silence manifests a mode of capable being in which we have an awareness of the awareness of the awareness of being with being whereby we can constitute and create a shared world of meaning(s) through poetically presencing our being as being with others. The doubling and tripling of the term "awareness" refers to five contextual levels of awareness, which are analyzed, including immediate self-awareness, immediate objective awareness, reflective awareness, reflexive awareness, and contemplative awareness. -

Natural Law in the Renaissance Period, We Must Look Elsewhere

THE NATURAL LAW IN THE RENAISSANCE PERIOD* Heinrich A. Rommen I T HE Renaissance period is usually associated with the Arts and with Literature; it is considered as a new birth of the Greek and Roman classics but also as the discovery of a new sense of life, as a period in which the autonomous individual, as the person in a pronounced meaning, escapes from the pre-eminence of the clergy and a morality determined by the Church. Nourished by the rediscovered philosophy of life of the classics, an emancipation takes place of the man of the world, of the man of secular learning, and of the artist and the poet, who set themselves up as of their own right beside, not against, the secular clergy and the learned monk. In politics this means the dissolution of the medieval union of Church and Empire in favor of the now fully devel- oped nation-states and city-republics which stress their autonomy against the Church as against the Empire. While the Renaissance, thus conceived, was of tremen- dous significance, it is nevertheless true that as such it con- tributed little for the development of the theory of Nat- ural Law. The reason for this is that the Humanists were admirers of the stoic philosophy and of the great orator, Cicero, the elegant popularizer of the stoic philosophy and of the philosophical ideas of the Roman Law, which, * Also printed in the Summer, 1949, issue of the Notre Dame Lawyer. 89 NATURAtL LAW INSTITUTE PROCEEDINGS at that time, freed from the Canon Law, conquered the world again. -

Deconstructing and Reconstructing Hobbes Isaak I

Louisiana Law Review Volume 72 | Number 4 Summer 2012 Deconstructing and Reconstructing Hobbes Isaak I. Dore Repository Citation Isaak I. Dore, Deconstructing and Reconstructing Hobbes, 72 La. L. Rev. (2012) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol72/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Deconstructing and Reconstructing Hobbes Isaak I. Dore * ABSTRACT The political and legal philosophy of Thomas Hobbes is often misunderstood or oversimplified. The two most well-known aspects of his philosophy (the condition of man in the pre-political state of nature and his concept of sovereign power) are not properly connected to show the unity of his thought. However, systematic study shows that Hobbes’s political and legal philosophy has a sophisticated underlying unity and coherence. At the heart of this unity is Hobbes’s utilitarian consequentialist ethic, which remarkably anticipates the major strands of contemporary consequentialism. To explain the unity in Hobbes’s philosophy via his consequentialist thought, the Article deconstructs and reconstructs the principal elements of Hobbes’s concept of sovereign obligation, his deism and theory of the divine covenant, his conceptions of the state of nature, the duties of the sovereign in civil society, and the rights and duties following from subject to sovereign and sovereign to subject. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ..........................................................................816 I. Hobbes and Consequentialism .............................................817 A. -

Protean Madness and the Poetic Identities of Smart, Cowper, and Blake

Protean Madness and the Poetic Identities of Smart, Cowper, and Blake Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Richard Paul Stern 1 Statement of Originality I, Richard Paul Stern, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Richard Stern Date: 15/09/2016 2 Abstract This thesis offers a comparative analysis of the poetic identities of Christopher Smart (1722-71), William Cowper (1731-1800) and William Blake (1757) in the context of contemporary understandings of madness and changing ideas of personal and spiritual identity from c.1750-1820. Critical attention is focused on the chameleonic status of madness in its various manifestations, of which melancholy, particularly in its religious guise, is particularly important. -

Ec-1000 Ec-1000 / M-1000

JAKE E LEE TOMI KOIVUSAARI CHRIS GARZA ALEX DEROSSO LUKE Kilpatrick ROB holliday DIEGO VERDUZCO BAZIE CRAIG GOLDY DeLuxe Amorphis Suicide Silence Parkway Drive Marilyn Manson, Prodigy Ill Niño The 69 Eyes Dio SERIES SPECIFICATIONS ec-1000fr ec-1000fm ec-1000fm w/Duncans ec-1000Qm SPECIFICATIONS ec-1000 BLK ec-1000 SW ec-1000 VB m-1000 m-1000fm CONSTRUCTION / SCALE Set-Neck / 24.75” Set-Neck / 24.75” Set-Neck / 24.75” Set-Neck / 24.75” CONSTRUCTION / SCALE Set-Neck / 24.75” Mahogany Set-Neck / 24.75” Set-Neck / 24.75” Set-Thru / 25.5” Set-Thru / 25.5” BODY Mahogany w/ Flamed Maple Top Mahogany w/ Flamed Maple Top Mahogany w/ Flamed Maple Top Mahogany w/ Quilted Maple Top BODY Mahogany Mahogany Mahogany Alder Alder w/ Flamed Maple Top NECK / FINGERBOARD Mahogany / Rosewood Mahogany / Rosewood Mahogany / Rosewood Mahogany / Rosewood NECK / FINGERBOARD Mahogany / Rosewood Mahogany / Rosewood Mahogany / Ebony Maple / Rosewood Maple / Rosewood NUT 42mm Locking 42mm Earvana Compensated 42mm Earvana Compensated 42mm Earvana Compensated NUT 42mm Earvana Compensated 42mm Earvana Compensated 42mm Earvana Compensated 43mm Locking 43mm Locking NECK CONTOUR Thin U Thin U Thin U Thin U NECK CONTOUR Thin U Thin U Thin U Extra Thin U Extra Thin U FRETS 24 XJ 24 XJ 24 XJ 24 XJ FRETS 24 XJ 24 XJ 24 XJ 24 XJ 24 XJ HARDWARE Black Nickel Black Nickel Chrome Black Nickel HARDWARE Gold Black Nickel Gold Black Nickel Black Nickel TUNERS ESP ESP Locking ESP Locking ESP Locking TUNERS ESP Locking ESP Locking ESP Locking Grover Grover BRIDGE Floyd Rose 1000 Series -

The Family Institution: Identity, Sovereignty, Social Dimension

Philosophy and Canon Law Vol. 1 The Family Institution: Identity, Sovereignty, Social Dimension Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego • Katowice 2015 Editor-in-Chief Andrzej Pastwa Deputy Editor-in-Chief Pavol Dancák Members of the Board Krzysztof Wieczorek (Chair of Philosophy Department) Tomasz Gałkowski (Chair of Law Department) International Advisory Board Chair Most Rev. Cyril Vasil’ (Pontifical Oriental Institute, Roma, Italy) Members of the Board Libero Gerosa (Faculty of Theology in Lugano, Switzerland), Wojciech Góralski (Cardinal Ste- fan Wyszyński University, Warsaw, Poland), Stephan Haering (Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Germany), Janusz Kowal (Pontifical Gregorian University, Roma, Italy), V. Bradley Lewis (Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C., USA), Wilhelm Rees (University of Innsbruck, Austria), David L. Schindler (Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C., USA), Santiago Sia (National University of Ireland, Dublin, Ireland), Zbigniew Suchecki (Pon- tifical University Antonianum, Roma, Italy) Referees of the Board Miguel Bedolla (University of Texas, San Antonio, USA), Alexandru Buzalic (Babeş-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, Romania), Francišek Čitbaj (University of Prešov, Slovak Republic), Roger Enriquez (University of Texas, San Antonio, USA), Silvia Gáliková (University of Trnava, Slovak Republic), Edward Górecki (Palacký University, Olomouc, Czech Republic), John P. Hit- tinger (University of St. Thomas, Houston, USA), Piotr Kroczek (Pontifical University of John Paul II, Cracow, Poland), -

Jerry Cantrell Jerry Cantrell

Jerry Cantrell Jerry Cantrell - vocals / guitar Robert Trujillo - bass Mike Bordin - drums From the lyrically and sonically mournful “Psychotic Break” to when the mental and musical exorcism of Jerry Cantrell's nearly 73-minute aural Degradation Trip concludes with the lovely, somnolent, bluesy strains of “Gone,” the singer/guitarist's Roadrunner debut is a sundry and sometimes scary journey to the center of a psyche. It may not always be a pretty trip, but it's a close-to-the-bone excursion that haunts both its creator and its listeners. As the multi-faceted artist relates, “In '98, I locked myself in my house, went out of my mind and wrote 25 songs,” says the then-fully-bearded Cantrell. “I rarely bathed during that period of writing; I sent out for food, I didn't really venture out of my house in three or four months. It was a hell of an experience. The album is an overview of birth to now. That's all,” he grins, though the visceral and haunting songs, by turns soaring and raw, do reflect that often-naked and sometimes-grim truth. “Boggy Depot [his 1998 solo bow] is like Kindergarten compared to this,” he furthers. “The massive sonic growth from Boggy Depot to Degradation Trip is comparable to the difference between our work in the Alice In Chains albums Facelift to Dirt, which was also a tremendous leap.” And all of Cantrell's 25 prolifically penned songs will see the light of day by 2003. Degradation Trip, which will be released June 18, is comprised of 14 songs from the personal, transcendent writing marathon that inspired such self-searching cuts as “Bargain Basement Howard Hughes,” “Hellbound,” and “Profalse Idol.” The second batch of songs—“as sad and brutal as Degradation Trip” —Cantrell promises, are due out on Roadrunner 2003.