Be Afraid to Go to the Doctor: a Thematic Analysis of Systemic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Primetime & Ott Programming

NETWORK PRIMETIME & OTT PROGRAMMING Flash #2 - 12 October 2018 Two weeks of the 2018-19 primetime season are behind us and the third week is in motion. Two weeks does not a season make as we continue to look at the overall network landscape and what is happening so far. Aside from the traditional ratings, we continue to review our perspective on the performance of the new and returning programs across social media and what impact that may have. Next week, we’ll have a look at the CW premieres and will mix it up a little with HUT/PUT overviews, freshman series week-to-week performances, genre breakdowns and a first look at L+SD versus L+7 data. This FLASH includes: ▪ CHART TOPPERS: Weekly Primetime Wrap-Up-top network and cable performers Page 1 ▪ BY THE NUMBERS-overall network primetime and 10:30-11PM performance Pages 2-3 ▪ TOP IT OFF: TOP 10, TOP 15, TOP 25 PROGRAMS Pages 3-4 ▪ TOP 25 PROGRAMS: NETWORK TALLY Page 4 ▪ ARE YOU READY FOR SOME SUNDAY NIGHT FOOTBALL? Page 5 ▪ WHERE DO THE FRESHMAN SERIES STAND? Page 5-6 ▪ SCORECARD: WHO TOOK THE NIGHT? Page 7 ▪ ON THE CABLE FRONT-a quick look at cable’s primetime ratings Pages 7-8 ▪ WHAT’S THE BUZZ-a review of social media and how it impacts the new TV season Pages 8-11 WEEKLY HEADLINES ▪ Whether because of all the social controversy or despite it, THE NEIGHBORHOOD was the top debuting series this week. FBI surpassed MANIFEST in total viewers. GOD FRIENDED ME was in the top 3 of the freshman entries this week and registered the most gains on Facebook after air. -

MIMI MELGAARD Costume Designer

MIMI MELGAARD Costume Designer PROJECTS DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS STATION 19 Paris Barclay Chris Larson-Nitzsche, Betsy Beers Pilot Shonda Rhimes / ABC GREY’S ANATOMY Seasons 2 - 14 RoB Corn, Bill D’Elia, Sara White, RoB Corn, Betsy Beers Tom Verica, Shonda Rhimes / ABC Jeannot Szwarc, Julie Anne RoBinson, Dan Minahan PRIVATE PRACTICE Pilot & Season 1 Julie Anne RoBinson, Ann KindBerg, Betsy Beers Mark Tinker Shonda Rhimes / ABC & Various Directors COMMANDER-IN-CHIEF Series Dan Minahan, Rod Lurie / Touchstone / ABC Vincent Misiano & Various Directors THE INSIDE Pilot and Series Tim Minear Gareth Davies / Imagine / FBC & Various Directors AMERICAN DREAMS Series Various Directors Jim Chory, David Semel, Jonathan Prince NBC DEMARCO AFFAIRS Pilot Michael Dinner Neely Swanson, David E. Kelley / ABC THE BROTHERHOOD OF POLAND, N.H. Various Directors Michael Pressman, Alice West Series David E. Kelley / CBS 111 GRAMERCY PARK Pilot Bill D’Elia David Latt / NBC GIRL’S CLUB Series Various Directors RoB Corn, David E. Kelley / FOX ALLY McBEAL Series Various Directors Bill D’Elia, David E. Kelley / FOX MORE, PATIENCE Pilot Jon TurteltauB Gavin Polone / ColumBia-TriStar TURN IT UP RoBert Adetuyi Bennett Walsh / New Line ROSWELL Series Various Directors Carol Trussell / Fox DAY ONE Pilot Michael Katleman Grace Gilroy / Jim Sharp / Regency GRAPEVINE Pilot & Series David Frankel CBS Studios DROP DEAD GORGEOUS Feature Film Michael Patrick Jann Claire Best / New Line BROWNS REQUIEM Feature Film Jason Freeland Main Street Media LATE LAST NIGHT Feature Film Steve Brill Jim Burke / Screenland Pictures THREE Pilot Michael Katleman Paramount Pictures / MTV ENEMY Pilot Michael Katleman Sony Pictures BLACK CIRCLE BOYS Matthew Carnahan Lunaria Films Official Selection – Sundance Film Festival HOW TO BE A PLAYER Feature Film Lionel Martin Island Pictures BLOODHOUNDS MOW Michael Katleman USA Network THE LITTLE DEATH Feature Film Jan Verhayen Island Pictures . -

Harry Belden Actor HAIR/EYES: Brown/Brown HEIGHT/WEIGHT: 5’11”/175Lbs

Harry Belden Actor HAIR/EYES: Brown/brown HEIGHT/WEIGHT: 5’11”/175lbs FILM/COMMERCIAL Chicago Med - NBC Co-Star Martha Mitchell Proven Innocent - FOX Co-Star Howard Deutch Chicago Fire - NBC Co-Star (Cut Scene) Leslie Libman Naked Juice: However You Healthy Meditator/Worker Krystina Archer Cellcom Principal Kipp & KC Norman Tire Rack Principal George Zwierzynski JEWEL-OSCO Lead Sandro Miller THEATRE The King’s Speech Footman u/s CST/ US-CA 2020 Michael Wilson Tour The Brothers Grimm Wilhelm/Jacob Grimm Arranmore Arts Lara Filip The Stinky Cheese Giant Griffin Theatre-NYC William Massolia Man Tour Letters Home JeremyLussi/MattHardman Griffin Theatre William Massolia Captain Planet & the Various/Sketch Show The Second City Amanda Christine Frawley Prisoner of Azkaban (Studio Show) TRAINING BFA: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Second City Training Center Acting: Daniel Sullivan, Robert G. Anderson, Lisa Dixon, Tom Mitchell, Janelle Snow, Amy J Carle Improv: Matthew Van Colton, Sam Super, James Wittington Voice Over: Dave Leffel, Susan Schuld Musical Theatre: Gene Scheer, Justin Brauer Movement and Stage Combat: Robin McFarquhar, Zev Steinberg SPECIAL SKILLS Judo, guitar (beginner), dialects (British R.P., Estuary, Cockney, Italian, Russian, Irish, French, Southern Plantation, more available upon request), can do clapping push-ups, Certified Personal Trainer, knows more about Batman than most people should, has a perfectly pointed foot. CPR/AED/First Aid Certified. . -

TV Listings Aug21-28

SATURDAY EVENING AUGUST 21, 2021 B’CAST SPECTRUM 7 PM 7:30 8 PM 8:30 9 PM 9:30 10 PM 10:30 11 PM 11:30 12 AM 12:30 1 AM 2 2Stand Up to Cancer (N) NCIS: New Orleans ’ 48 Hours ’ CBS 2 News at 10PM Retire NCIS ’ NCIS: New Orleans ’ 4 83 Stand Up to Cancer (N) America’s Got Talent “Quarterfinals 1” ’ News (:29) Saturday Night Live ’ Grace Paid Prog. ThisMinute 5 5Stand Up to Cancer (N) America’s Got Talent “Quarterfinals 1” ’ News (:29) Saturday Night Live ’ 1st Look In Touch Hollywood 6 6Stand Up to Cancer (N) Hell’s Kitchen ’ FOX 6 News at 9 (N) News (:35) Game of Talents (:35) TMZ ’ (:35) Extra (N) ’ 7 7Stand Up to Cancer (N) Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News at 10pm Castle ’ Castle ’ Paid Prog. 9 9MLS Soccer Chicago Fire FC at Orlando City SC. Weekend News WGN News GN Sports Two Men Two Men Mom ’ Mom ’ Mom ’ 9.2 986 Hazel Hazel Jeannie Jeannie Bewitched Bewitched That Girl That Girl McHale McHale Burns Burns Benny 10 10 Lawrence Welk’s TV Great Performances ’ This Land Is Your Land (My Music) Bee Gees: One Night Only ’ Agatha and Murders 11 Father Brown ’ Shakespeare Death in Paradise ’ Professor T Unforgotten Rick Steves: The Alps ’ 12 12 Stand Up to Cancer (N) Shark Tank ’ The Good Doctor ’ News Big 12 Sp Entertainment Tonight (12:05) Nightwatch ’ Forensic 18 18 FamFeud FamFeud Goldbergs Goldbergs Polka! Polka! Polka! Last Man Last Man King King Funny You Funny You Skin Care 24 24 High School Football Ring of Honor Wrestling World Poker Tour Game Time World 414 Video Spotlight Music 26 WNBA Basketball: Lynx at Sky Family Guy Burgers Burgers Burgers Family Guy Family Guy Jokers Jokers ThisMinute 32 13 Stand Up to Cancer (N) Hell’s Kitchen ’ News Flannery Game of Talents ’ Bensinger TMZ (N) ’ PiYo Wor. -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

ALEX NEPOMNIASCHY, ASC Director of Photography Alexnepomniaschy.Com

ALEX NEPOMNIASCHY, ASC Director of Photography alexnepomniaschy.com PROJECTS Partial List DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS THE MARVELOUS MRS. MAISEL Daniel Palladino AMAZON STUDIOS / Nick Thomason Season 4 Amy Sherman-Palladino MIXTAPE Ti West ANNAPURNA PICTURES Series NETFLIX / Chip Vucelich, Josh Safran L.A.’S FINEST Eagle Egilsson SONY PICTURES TELEVISION Series Mark Tonderai Scott White, Jerry Bruckheimer WISDOM OF THE CROWD Adam Davidson CBS Series Jon Amiel Ted Humphrey, Vahan Moosekian Milan Cheylov Adam Davidson GILMORE GIRLS: A YEAR IN THE LIFE Amy Sherman- WARNER BROS. TV / NETFLIX Mini-series Palladino Daniel Palladino Daniel Palladino Amy Sherman-Palladino THE AMERICANS Thomas Schlamme DREAMWORKS / FX Season 4 Chris Long Mary Rae Thewlis, Chris Long Daniel Sackheim Joe Weisberg, Joel Fields THE MENTALIST Chris Long WARNER BROS. / CBS Season 7 Simon Baker Matthew Carlisle, Bruno Heller Nina Lopez-Corrado Chris Long STANDING UP D.J. Caruso ALDAMISA Janet Wattles, Jim Brubaker Ken Aguado, John McAdams BLUE BLOODS David Barrett CBS Seasons 4 & 5 John Behring Jane Raab, Kevin Wade Alex Chapple Eric Laneuville I AM NUMBER FOUR D.J. Caruso DREAMWORKS Add’l Photography Sue McNamara, Michael Bay BIG LOVE Daniel Attias HBO Season 4 David Petrarca Bernie Caulfield THE EDUCATION OF CHARLIE BANKS Fred Durst Marisa Polvino, Declan Baldwin TAKE THE LEAD Liz Friedlander NEW LINE Diane Nabatoff, Michelle Grace CRIMINAL MINDS Pilot Richard Shepherd CBS / Peter McIntosh NARC Joe Carnahan PARAMOUNT PICTURES Nomination, Best Cinematography – Ind. Spirit -

COLEMAN, ROSALYN 2020 Resume

ROSALYNFilm COLEMAN THE IMMORTAL JELLYFISH Dusty Bias MISS VIRGINIA R.J. Daniel Hanna EVOLUTION OF A CRIMINAL Darious Clarke Monroe/Spike Lee Producer IT’S KIND OF A FUNNY STORY Ryan Fleck & Ana Bolden TWELVE Joel Schumacher FRANKIE & ALICE (w/Halle Berry) Geoffrey Sax BROOKLYN’S FINEST Antwoine Fuqua/Warner Bros. BROWN SUGAR (w/Taye Diggs) Rick Famuyiwa/20th Century Fox VANILLA SKY (w/Tom Cruise) Cameron Crowe/ Artisan OUR SONG (w/Kerry Washington) Jim McKay/Stepping Pictures MUSIC OF THE HEART (w/Meryl Streep) Wes Craven/Miramax MIXING NIA Alison Swan/Independent PERSONALS Mike Sargent/Independent Television JESSICA JONES Netflix BULL CBS MADAM SECRETARY CBS BLUE BLOODS CBS ELEMENTARY CBS WHITE COLLAR USA SPRING/FALL (Pilot) HBO Pilot NURSE JACKIE Showtime MERCY (Pilot) NBC NEW AMSTERDAM FOX KIDNAPPED (recurring) NBC LAW & ORDER SVU & CI NBC/Jim McKay/Michael Zinberg DEADLINE NBC OZ (recurring) HBO/Alex Zakrzewski D.C. (recurring) WB/Dick Wolf producer THE PIANO LESSON Lloyd Richards/Hallmark Hall of Fame THE DITCHDIGGER’S DAUGHTERS Johnny Jensen/Family Channel Broadway TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD Bartlett Shear TRAVESTIES us Patrick Marber/Roundabout Theatre Co. THE MOUNTAINTOP us Kenny Leon RADIO GOLF us Kenny Leon SEVEN GUITARS Lloyd Richards THE PIANO LESSON Lloyd Richards MULE BONE Michael Shultz Off Broadway NATIVE SON Acting Company/Yale Rep/ Seret Scott SCHOOL GIRLS OR THE AFRICAN MEAN GIRLS PLAY us MCC /Rebecca Taichman PIPELINE us Lincoln Center Theatre/Lileana Blain-Cruz BREAKFAST WITH MUGABE Signature Theater/David Shookov ZOOMAN & THE SIGN Signature Theatre/Steven Henderson WAR Rattlestick Theatre/Anders Cato THE SIN EATER 59 E. -

Speed Kills / Hannibal Production in Association with Saban Films, the Pimienta Film Company and Blue Rider Pictures

HANNIBAL CLASSICS PRESENTS A SPEED KILLS / HANNIBAL PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH SABAN FILMS, THE PIMIENTA FILM COMPANY AND BLUE RIDER PICTURES JOHN TRAVOLTA SPEED KILLS KATHERYN WINNICK JENNIFER ESPOSITO MICHAEL WESTON JORDI MOLLA AMAURY NOLASCO MATTHEW MODINE With James Remar And Kellan Lutz Directed by Jodi Scurfield Story by Paul Castro and David Aaron Cohen & John Luessenhop Screenplay by David Aaron Cohen & John Luessenhop Based upon the book “Speed Kills” by Arthur J. Harris Produced by RICHARD RIONDA DEL CASTRO, pga LUILLO RUIZ OSCAR GENERALE Executive Producers PATRICIA EBERLE RENE BESSON CAM CANNON MOSHE DIAMANT LUIS A. REIFKOHL WALTER JOSTEN ALASTAIR BURLINGHAM CHARLIE DOMBECK WAYNE MARC GODFREY ROBERT JONES ANSON DOWNES LINDA FAVILA LINDSEY ROTH FAROUK HADEF JOE LEMMON MARTIN J. BARAB WILLIAM V. BROMILEY JR NESS SABAN SHANAN BECKER JAMAL SANNAN VLADIMIRE FERNANDES CLAITON FERNANDES EUZEBIO MUNHOZ JR. BALAN MELARKODE RANDALL EMMETT GEORGE FURLA GRACE COLLINS GUY GRIFFITHE ROBERT A. FERRETTI SILVIO SARDI “SPEED KILLS” SYNOPSIS When he is forced to suddenly retire from the construction business in the early 1960s, Ben Aronoff immediately leaves the harsh winters of New Jersey behind and settles his family in sunny Miami Beach, Florida. Once there, he falls in love with the intense sport of off-shore powerboat racing. He not only races boats and wins multiple championship, he builds the boats and sells them to high-powered clientele. But his long-established mob ties catch up with him when Meyer Lansky forces him to build boats for his drug-running operations. Ben lives a double life, rubbing shoulders with kings and politicians while at the same time laundering money for the mob through his legitimate business. -

Logan Lucky- for Distribution in China

Beat: Miscellaneous American Director Steven Soderbergh Sold -Logan Lucky- for distribution in China By Shanghai-based Linmon Pictures PARIS - BEIJING - HOLLYWOOD, 15.05.2016, 08:40 Time USPA NEWS - Shanghai-based Linmon Pictures has acquired Steven Soderbergh's top-secret directorial project 'Logan Lucky' for distribution in China. Channing Tatum, Michael Shannon and Adam Driver are set to star in the film, which will mark Soderbergh's return to feature filmmaking.... Shanghai-based Linmon Pictures has acquired Steven Soderbergh's top-secret directorial project 'Logan Lucky' for distribution in China. Channing Tatum, Michael Shannon and Adam Driver are set to star in the film, which will mark Soderbergh's return to feature filmmaking. The deal was part of a trio of sales made by FilmNation to Linmon. The Chinese company also has acquired Michael Grandage's 'Genius', starring Colin Firth, Jude Law and Nicole Kidman, and forthcoming sci-fi 'Redivider', starring Dan Stevens and directed by Tim Smit. China release dates for the three films will be determined by the country's state regulators. Steven Soderbergh is an American film producer, director, screenwriter, cinematographer and editor. His indie drama 'Sex, Lies, and Videotape' (1989) won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, and became a worldwide commercial success, making the then-26-year-old Soderbergh the youngest director to win the festival's top award. He is best known for directing critically acclaimed commercial Hollywood films like : - Crime comedy 'Out of Sight' (1998), - The biographical film 'Erin Brockovich' (2000), - The crime drama film 'Traffic' (2000) - The 2001 remake of the comedy heist film 'Ocean's 11', - The comedy-drama 'Magic Mike' (2012) (...) Linmon Pictures was launched in 2014 by Zhou, former head of Shanghai Media Group, and fellow SMG albums Su Xiao, Chen Fei and Xu Xiao´ou. -

Rebooting Roseanne: Feminist Voice Across Decades

Home > Vol 21, No 5 (2018) > Ford Rebooting Roseanne: Feminist Voice across Decades Jessica Ford In recent years, the US television landscape has been flooded with reboots, remakes, and revivals of “classic” nineties television series, such as Full/er House (1987-1995, 2016- present), Will & Grace (1998-2006, 2017-present), Roseanne (1988-1977, 2018), and Charmed (1998-2006, 2018-present). The term “reboot” is often used as a catchall for different kinds of revivals and remakes. “Remakes” are derivations or reimaginings of known properties with new characters, cast, and stories (Loock; Lavigne). “Revivals” bring back an existing property in the form of a continuation with the same cast and/or setting. “Revivals” and “remakes” both seek to capitalise on nostalgia for a specific notion of the past and access the (presumed) existing audience of the earlier series (Mittell; Rebecca Williams; Johnson). Reboots operate around two key pleasures. First, there is the pleasure of revisiting and/or reimagining characters that are “known” to audiences. Whether continuations or remakes, reboots are invested in the audience’s desire to see familiar characters. Second, there is the desire to “fix” and/or recuperate an earlier series. Some reboots, such as the Charmed remake attempt to recuperate the whiteness of the original series, whereas others such as Gilmore Girls: A Life in the Year (2017) set out to fix the ending of the original series by giving audiences a new “official” conclusion. The Roseanne reboot is invested in both these pleasures. It reunites the original cast for a short-lived, but impactful nine-episode tenth season. -

See More of Our Credits

ANIMALS FOR HOLLYWOOD PHONE: 661.257.0630 FAX: 661.269.2617 BEAUTIFUL BOY OLD MAN AND THE GUN ONCE UPON A TIME IN VENICE DARK TOWER HOME AGAIN PUPSTAR 1 & 2 THE HATEFUL EIGHT 22 JUMP STREET THE CONJURING 2 PEE-WEE’S BIG HOLIDAY DADDY’S HOME WORLD WAR Z GET HARD MORTDECAI 96 SOULS THE GREEN MILE- WALKING THE PURGE: ANARCHY DON’T WORRY, HE WON’T GET THE MILE FAR ON FOOT THE LONE RANGER DUE DATE THE FIVE YEAR ENGAGEMENT ZERO DARK THIRTY THE CONGRESS MURDER OF A CAT THE DOGNAPPER OBLIVION HORRIBLE BOSSES CATS AND DOGS 2 – THE SHUTTER ISLAND POST GRAD REVENGE OF KITTY GALORE THE DARK KNIGHT RISES YOU AGAIN THE LUCKY ONE HACHIKO FORGETTING SARAH MARSHALL TROPIC THUNDER MAD MONEY OVER HER DEAD BODY THE HEARTBREAK KID UNDERDOG STUART LITTLE THE SPIRIT REXXX – FIREHOUSE DOG THE NUMBER 23 IN THE VALLEY OF ELAH YEAR OF THE DOG CATS AND DOGS MUST LOVE DOGS CATWOMAN BLADES OF GLORY STUART LITTLE 2 PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN P I RA T ES O F THE CARIBBEAN PIRATES OF THE CARIBBEAN – - THE CURSE OF THE – DEAD MAN’S CHEST WORLD’S END BLACK PEARL CHEAPER BY THE DOZEN 2 THE DEPARTED EVERYTHING IS ILLUMINATED THE PACIFIER ALABAMA MOON RUMOR HAS IT NATIONAL TREASURE ELIZABETHTOWN ALONE WITH HER PETER PAN THE GREEN MILE TROY WALK THE LINE THE HOLIDAY RAISING HELEN MOUSE HUNT CHRISTMAS WITH THE CRANKS OPEN RANGE BATMAN AND ROBIN THE MEXICAN PAULIE BUDDY KATE AND LEOPOLD WILLARD Animals for Hollywood - ph. 661.257.0630 e-mail: [email protected] pg. -

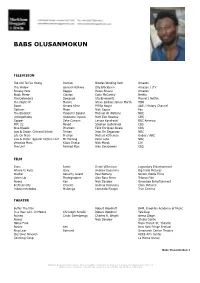

Babs Olusanmokun

BABS OLUSANMOKUN TELEVISION Too Old To Die Young Damian Nicolas Winding Refn Amazon The Widow General Azikiwe Olly Blackburn Amazon / ITV Sneaky Pete Reggie Helen Shaver Amazon Black Mirror Clayton Colm McCarthy Netflix The Defenders Sowande Uta Briesewitz Marvel / Netflix The Night Of Marvin Steve Zaillian/James Marsh HBO Roots Omoro Kinte Phillip Noyce A&E / History Channel Gotham Mace Nick Copus Fox The Blacklist Yaabari's Soldier Michael W. Watkins NBC Unforgettable Goodacre Oyensi Matt Earl Beesley CBS Copper Zeke Canaan Larysa Kondracki BBC America NYC 22 Fouad Stephen Gyllenhaal CBS Blue Bloods Phantom Félix Enríquez Alcalá CBS Law & Order: Criminal Intent Tristan Jean De Segonzac NBC Life On Mars Preston Michael Katleman Kudos / ABC Law & Order: Special Victims Unit Mr Marong Peter Leto NBC Veronica Mars Kizza Oneko Nick Marck CW The Unit Painted Man Alex Zakrzewski CBS FILM Dune Jamis Denis Villeneuve Legendary Entertainment Where Is Kyra Gary Andrew Dosunmu Big Indie Pictures Shelter Security Guard Paul Bettany Screen Media Films Listen Up Photographer Alex Ross Perry Tribeca Film Ponies Ken Nick Sandow Greenbox Entertainment Restless City Cravate Andrew Dosunmu Clam Pictures Indocumentados Mubenga Leonardo Ricagni True Cinema THEATER Buffer The Man Robert Woodruff BAM, Brooklyn Academy of Music In a Year with 13 Moons Christoph Smolik Robert Woodruff Yale Rep Ruined Cmdr. Osembenga Charles R. Wright Arena Stage Ponies Nick Sandow Studio Dante Home Free Mass Transit St. Theatre Ponies Ken New York Fringe Festival King Lear Edmund Greenwich Center Theatre Sky Over Nineveh HERE Arts Center Counting Coup La Mama Annex Babs Olusanmokun 1 Markham Froggatt & Irwin Limited Registered Office: Bank Gallery, High Street, Kenilworth, Warwickshire, CV8 1LY Registered in England No.