STRANGER SPECIES by DEVIN LATHAM B.A. University Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For the First Lesson, Please Have

For the first lesson, please have: There are a few things you will need to prepare prior to your first lesson. 5 Steps to Getting Started: 1. Have Pre-Made Ice (2 Sheets of more if possible) If you have an ice bucket or scoop that would also be great (but not required). 2. Have a Lime + Lemon or Oranges (for cutting practice) 3. Have Glasses (as many as possible) out and on the counter ready for lesson (to match diagram below) (if you do not have all of the glasses please don’t worry or go purchase them) 4. Have a Fruit Cutting knife. (Can be a steak knife) 5. Have your Kit On Your Counter (with all of the above) and a Pen Kit Diagram Includes: 1- 4 Pronged Strainer 1-Stainless Steel 28 Oz Shaker 1-Stainless Steel 1 Oz/1.5Oz Jigger 2-Colored Pourer Nozzles Practice cocktail straws 2-36 Oz’ Practice Liquor Bottles Food colored liquid for practice 1-Colored Shot Glass 1 Oz (Glasses to be provided by you) -—STOP— THE FOLLOWING PAGES ARE ONLY TO BE COMPLETED DURING THE LESSON On each page, underlined is the action either the instructor or student must do INSTRUCTOR- This is the NEW Summer 2013 Curriculum (please follow in the below order:) Step 1: Go over glasses and Tools and set bar (p. 1-3) Step 2: Free Pour Step 3: Shot pour Step 4: Cutting Fruit Step 5: Mixed drinks Step 6: How to use a strainer and shaker Step 7: Instructor Orders drinks from student/ Time student’s drink making with stopwatch Step 8: Checking IDs Step 9 OPTIONAL Step 1: Glasses Figure 1-5 1. -

Defies Convention Palacios, Chief Winemaker of Bodegas Faustino in Rioja Alavesa, Spain

OCTOBER 2018 • $6.95 Rioja’sNEWFOUND EDGE AFTER MORE THAN 150 YEARS OF PRODUCTION, FAUSTINO Rafael Martínez Defies Convention Palacios, Chief Winemaker of Bodegas Faustino in Rioja Alavesa, Spain. TP1018_001-31_KNV5.indd 1 RIOJA’S 10/1/18 6:29 PM NEWFOUND tastingpanel TP1018_001-31_KNV5.indd 2 10/1/18 6:29 PM tastingTHE panel tastingpanel MAGAZINE October 2018 • Vol. 76 No. 9 editor in chief publisher / editorial director vp / associate publisher managing editor Anthony Dias Blue Meridith May Rachel Burkons Jesse Hom-Dawson [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 818-990-0350 CONTRIBUTORS senior design director Michael Viggiano [email protected] Erica Bartel, Kim Beto, Brandon Boghosian, Randy Caparoso, Madelyn vp, sales and marketing Gagnon, Albert Letizia, Michelle Metter, Jennifer Olson, Alexander [email protected] Rubin, Benjamin Rusnak, Grace Stufkosky, James Tran, Paul Van Hoy Bill Brandel senior wine editor Published eleven times a year Jessie Birschbach [email protected] ISSN# 2153-0122 USPS 476-430 senior editor Chairman/CEO: Anthony Dias Blue Kate Newton [email protected] President/COO: Meridith May special projects editor Subscription Rate: $36 One Year; $60 Two Years; Single Copy: $6.95 David Gadd [email protected] For all subscriptions, email: [email protected] Periodicals Postage Paid at Van Nuys and at additional mailing offices east coast editor David Ransom Devoted to the interests and welfare of United States restaurant and retail store licensees, wholesalers, rocky mountain editor importers and manufacturers in the beverage industry. Ruth Tobias POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: The Tasting Panel Magazine features editor 6345 Balboa Blvd; Ste 111, Encino, California 91316, Michelle Ball 818-990-0350 editor-at-large Cliff Rames STATEMENT OF OWNERSHIP wine country editor The Material in each issue of The Tasting Panel Magazine is protected Chris Sawyer by U.S. -

Bar (Beer, Wine, Cocktail and Alcohol)

425.576.1000 [email protected] BAR MENU northwest wine package P I N O T G RIS , 2 0 1 6 | C O O P E R M O U N T A I N V INEYARDS , W I L L A M E T T E V A L L E Y OR F REYJA , 2 0 1 7 | G A R D V I N T N E R S & L A W R E N C E V INEYARDS , C O L U M B I A V A L L E Y WA R OSE , 2 0 1 7 | M ILB R A N D T V INEYARDS , C OLU M B I A V A L L E Y WA C A B E R N E T S AUVI GNON , 2 0 1 6 | D ISRUPTION , C O L U M B I A V A L L E Y WA R E D B LEND , 2 0 1 5 | D ISRU PTION , C OLU M B I A V A L L E Y WA northwest craft beer package S E A S O N A L IPA | H EFEW E I Z E N | R O G U E D E A D G U Y A L E | D E S C H U T E S B L A C K B U T T E P O R T E R | S T E L L A A RTOIS mixed drink liquor package L IQUOR : V O D K A | T E Q U I L A | R U M | W HIS K E Y | G I N | S COT CH M I XERS : C O K E | D I E T C O K E | S P R I T E | G I N G E R A L E | T O N I C | S ODA W ATER | J UICE S { CRANBERRY , PINEAPPLE , ORANGE , GRAPEFRUIT } | S W E E T N ’ S O U R | T R I P L E S E C | B ITTERS G ARNISHES : C OCKT A I L C HERRIES | C O C K T A I L O L I V E S | F R E S H M I N T | S A L T & S U G A R | L E M O N S & L IMES - M I X E R S & G ARNISHES AVAILABLE | C LIENT TO PROVIDE OWN L I Q U O R S ELECTIONS - bubbles C H A M P A G N E T OAST A N D M ARTINELLI ’ S S PAR K L I N G C I D E R T OAST {2 O Z } C H A M P A G N E P O UR { 5 OZ} M IMOSAS : SPA RKLING WINE & ORA N G E J U I C E M I M O S A B AR: SPARK L I N G W I N E & ASSORTED JUICES { ORANGE , GRA P EFRUIT , PINEAPPLE , GUAVA } additional services B E E R A N D W I N E H A N D L I N G F EE Client to provide all beer and wine | Twelve Baskets Catering to provide bartending services A LCOHOL H A N D L I N G F EE Client to provide all beer, wine and liquor | Twelve Baskets Catering to provide bartending services, mixers and garnishes P RE- E V E N T B E V E R A G E C HILLING F EE | BASED ON EVENT SIZE Client to deliver all alcohol to Twelve Baskets Catering | Includes chilling, storing and transporting of all alcohol to event 1 - 50 GUESTS 51- 1 5 0 GUESTS p. -

Maximizing the Efficiency of a Speed Rail for the Preparation of Alcoholic Beverages

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 8-2010 Maximizing the efficiency of a speedail r for the preparation of alcoholic beverages. Ashley S. Riley University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Riley, Ashley S., "Maximizing the efficiency of a speedail r for the preparation of alcoholic beverages." (2010). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1209. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1209 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MAXIMIZING THE EFFICIENCY OF A SPEED RAIL FOR THE PREPARATION OF ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES By Ashley S. Riley B.S. Mathematics, Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science In Industrial Engineering Department of Industrial Engineering J.B. Speed School of Engineering University of Louisville Louisville, KY August 2010 Copyright 2010 by Ashley Riley All rights reserved MAXIMIZING THE EFFICIENCY OF A SPEED RAIL FOR THE PREPARATION OF ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES By Ashley S. Riley B.S. Mathematics, Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College, 2009 A Masters thesis approved on July 16,2010 By the following Committee: Dr. -

Holyrood Distillery Opens in Edinburgh

AUGUST 9, 2019 | MODERN DISTILLERY AGE VOLUME 10 | NUMBER 24 Gin & Japanese Whisky Holyrood Distillery Opens in Edinburgh Holyrood Distillery, the first single malt whisky distillery in the center Post Double Digit Percent of Edinburgh, Scotland, for almost 100 years, opened on July 30, and daily guided distillery tours are offered. Growth in Global Travel Retail Special to Modern Distillery Age by IWSR, www.theiwsr.com Overall spirits volume and value in global travel retail increased in 2018, strengthened by gains in several categories. In total, spirits volume grew 2.5% in the channel last year, to reach 24.5 million nine-liter cases, with a value of $9.2 billion. The spirits categories which posted the largest volume increases in duty-free were Japanese whisky (up almost 20% vs. 2017), gin (15%), Scotch (4.9%) and U.S. whiskey (4.3%). Over the next five years, IWSR forecasts that global travel retail volume will grow by 2%, led by cane spirits (6.7%), Japanese whisky (6.4%) and gin (6.2%). By region, spirits volume is expected to grow 3.6% in Africa and the Middle East, 2.4% in Asia Pacific, 2.3% in the Americas and 1.2% in Europe (all figures compound annual growth rate 2018-2023). The retail L-R: Holyrood Distillery Cask Program – Laika, Dr. Jack Mayo & value of spirits in duty-free is estimated to reach David Robertson almost $10.4 billion by 2023. continued on page 2 The last operational single malt distillery in central Edinburgh was The Edinburgh Distillery (a.k.a. -

Pressley's at the Marina

Pressley’s at the Marina Starters Calamari Hand Tossed with sweet chili sauce 13.95 Bang-Bang Shrimp lightly breaded and fried & tossed with sweet red chili sauce 10.95 Wings Choose from 10 10.95 20 21.95 served with celery sticks & ranch 10.95/21.95 dressing choose from hot, mild, Carolina Gold BBQ, teriyaki, garlic butter, lemon pepper Lump Blue Crab Cake with buerre blanc and tomato preserve 13.95 Seasoned Shrimp Boil with Cocktail Sauce ¼ lb. 9.95 Homemade Wing Chips 8.95 sprinkled with blue cheese crumbles, served with homemade blue cheese dipping sauce Pressley’s Appetizer Cobo – choose 2 from below 13.95 Fried Mushrooms served with bistro sauce 8.95 Hushpuppies and Sweet Honey Butter 6.95 TooGooDoo Chicken Bites served with honey mustard 9.95 Mozzarella Sticks served with marinara or honey mustard 9.95 Fried Pickles served with ranch 5.95 Fried Clams served with cocktail and tarter sauces 8.95 Soups ’ Salads She-Crab Soup Cup 6.95 Bowl 9.95 Caesar Salad 6.95 Garden Salad 6.75 The Wedge 9.95 wedge of iceberg with bacon, tomato, blue cheese crumbles and balsamic vinaigrette Make Your Salad an Entrée For an additional Grilled Tuna 9.95 Grilled Salmon 8.95 Grilled Flat Iron Steak 10.95 Fried or Marinated Grilled Chicken 6.95 Fried or Boiled Shrimp 8.95 Fried Oysters 10.95 House Made Dressings: ranch, balsamic vinaigrette, Caesar, honey mustard, blue cheese, and 1000 island Steam Boat Sandwiches served with fries and coleslaw Fried Chicken 9.95 Marinated Chicken 9.95 Fried Flounder 9.95 Pressley’s Hand Formed Patty ½ Pound Cheeseburger -

Brand Calories Per Serving Pure Ethanol Not a Real Drink, For

ABV Brand Alcohol % Calories by Volume Per Serving Pure Ethanol 100% 238 calories per 1.5 oz Not a real drink, for comparison only Everclear 95% 226 calories per 1.5 oz Jose Cuervo Especial (Gold) 40% 96 calories per 1.5 oz Jose Cuervo Especial (Silver) 40% 96 calories per 1.5 oz Crown Royal - Special Reserve 40% 96 calories per 1.5 oz Knob Creek Bourbon 50% 120 calories per 1.5 oz Don Julio Blanco Tequila 40% 96 calories per 1.5 oz Ketel One Vodka 40% 96 calories per 1.5 oz Myers Original Dark Rum 40% 96 calories per 1.5 oz Pendleton Whisky 40% 96 calories per 1.5 oz Monarch Citron Vodka 35% 84 calories per 1.5 oz Smirnoff Vodka Blue Label 100 Proof 50% 121 calories per 1.5 oz Bulleit Rye 45% 109 calories per 1.5 oz Bulleit Bourbon 45% 109 calories per 1.5 oz Makers Mark 45.5% 110 calories per 1.5 oz Bacardi 151 Rum 75.5% 183 calories per 1.5 oz Vodka and Diet Coke 13.3% 258 calories per 12 oz Smirnoff Vodka Red Label 80 Proof 40% 97 calories per 1.5 oz Vodka - Royal Gate (generic) 80 proof 40% 97 calories per 1.5 oz Grey Goose Vodka 40% 97 calories per 1.5 oz 1910 Rye Whisky 40% 97 calories per 1.5 oz Bombay Sapphire Gin 47% 114 calories per 1.5 oz E&J Brandy 40% 97 calories per 1.5 oz Smirnoff Vodka Silver Label 90 Proof 45.2% 110 calories per 1.5 oz Bacardi Gold Rum 40% 98 calories per 1.5 oz Jack Daniels Whiskey 40% 98 calories per 1.5 oz Jack and Diet Coke 10% 195 calories per 12 oz Dalwhinnie Scotch Whisky 57.8% 141 calories per 1.5 oz Patron Anejo Tequila 40% 98 calories per 1.5 oz Patron Gran Patron Burdeos Anejo 40% 98 calories -

It on the Worm

BLAME IT ON THE WORM TOBY’S TEA: Wild Shot Mezcal, Vodka, Rum, FROZEN JACK & COKE: Triple Sec, sour mix & splash of Coke. Yeah! Jack and Coke! BLUE MEZCALITA: NUMBER JUAN PALOMA: Wild Shot Mezcal, Triple Sec, house Ron White’s Number Juan Reposado, margarita mix, fresh lime & a splash of Fresca, soda, & fresh lime. Blue Curacao on the rocks. LOOSE SKREW: SALTY LEMONADE: Skrewball Peanut Butter Whiskey, orange Wild Shot Mezcal, Grand Marnier, Triple NON-ALCOHOLIC juice & pineapple juice. Sec, lime juice, & sour mix on the rocks. COKE INDIGO KISS: DIET COKE Svedka Raspberry, Chambord, DeKuyper WILD SHOT MEZCALITA: SPRITE Peachtree Schnapps, sour mix & Sprite. Wild Shot Mezcal, Grand Marnier, agave DR. PEPPER Served in a chilled martini glass with a syrup, house margarita mix & fresh lime on BARQ’S ROOT BEER cherry. the rocks. LEMONADE RED BULL ENERGY DRINK OKLAHOMA BREEZE: PERFECT MEZCALITA: FRESCA Malibu, Triple Sec, pineapple juice, Wild Shot Mezcal, Grand Marnier, Triple sour mix & grenadine. DASANI BOTTLED WATER Sec, house margarita mix & fresh lime. WHISKEY GIRL: Jack Daniel’s, sour mix, & lemonade. CRIMSON & CREAM: AMERICAN FRITA: A refreshing blend of Cruzan Coconut Frozen margarita, strawberry & Blue Rum & Cruzan Pineapple Rum with a Curacao. blend of juices & cream. RON WHITE & BLUE: MASON JAR LYNCHBURG LEMONADE: Ron White’s Number Juan Reposado, Jack Daniel’s, Triple Sec & sour mix Triple Sec, house margarita mix, Blue topped with a splash of Sprite. Curacao & grenadine. STRAWBERRY LEMONADE: ROCK N ROLL Svedka Citron, strawberries, grenadine, MARGARITA: Sprite, & lemonade with a sugar rim. Rock n Roll Platinum Tequila & house I.L.T.B.: margarita mix with your choice of MULE: Milagro Reposado Tequila, Triple Sec, flavor: melon, raspberry, pomegranate, Svedka Vodka, ginger beer & our house margarita mix & a splash watermelon, or mango. -

SUBJECT: Floria Woodard, Bartender @ the Court of Two Sisters 613 Royal Street New Orleans, LA 70130 DATE: March 31, 2005 @ 2:00 P.M

FULL TRANSCRIPT: SUBJECT: Floria Woodard, bartender @ The Court of Two Sisters 613 Royal Street New Orleans, LA 70130 DATE: March 31, 2005 @ 2:00 p.m. LOCATION: The Court of Two Sisters bar INTERVIEWER: Amy Evans LENGTH: Approx. 42 minutes NOTE: Various sounds occur throughout this interview. Rather than mention them individually and interrupt the flow of the conversation, they are noted here: the restaurant staff can be heard in the background from time to time setting up for service, various voices can be heard in conversation, and the noise of a vacuum cleaner appears in portions of the audio. When the occurring sounds are an obvious interruption to the interview, they are noted in the transcript. * * * Amy Evans: This is Thursday, March thirty-first, two thousand and five, and I’m in New Louisiana in the French Quarter on Royal Street at The Court of Two Sisters with Floria known as Miss Flo—a bartender here. And, um, Miss Flo, would you mind saying your whole name for the record? Floria Woodard: My name is Floria Woodard, and I’m old as dirt. [Laughs] AE: [Laughs] You don’t look near old as dirt! FW: [Laughing] Oh! AE: May I ask your birthday? FW: My birthday is six, six, thirty-eight [June 6, 1938]. AE: Okay. And I understand you’ve been working here at The Court of Two Sisters for forty years or some such thing. FW: It’s close to forty. It’s thirty-eight years this February seventh, two thousand five. AE: Yeah? FW: And I’ve enjoyed it ever since I’ve been here. -

No Straw Needed: 30 Cocktail Recipes

No Straw Needed 30 cocktail recipes that good bartenders know and bad bartenders butcher No need to straw test Table of Contents Tools, Terms, & Tips ... 3 Glassware Key ... 4 Low Proof Cocktails ... 5 Vodka ... 6 - 7 Gin ... 8 - 10 Tequila & Mezcal ... 11 - 12 Rum ... 13 - 15 Whiskey ... 16 - 19 Cognac & Pisco ... 20 - 21 About Uncorkd ... 22 Cover photo by Jez Timms stocksnap.io/author/637 Tools, Terms, & Tips Bar Spoon - Long handled spoon used to stir cocktails and measure ingredients Stirring Vessel - A heavy glass container used to stir cocktails Cocktail Shaker - Metal shaker tins used to mix, dilute and chill cocktails Fine Strainer - Fine mesh strainer used to filter out small material like ice and herbs Hawthorne Strainer - Metal strainer with spring fitting used to strain shaken cocktails from shaker tin Julep Strainer - Convex metal strainer used to strain stirred drinks from glass containers Double Strain - After shaking a cocktail to be served without ice, straining through a Hawthorne strainer and a fine strainer Build - To assemble all ingredients in glass that it will be served in, no shaking or stirring Dry Shake - When making cocktails with egg whites, shake all ingredients without ice to emulsify egg whites and citrus, add ice and shake again Express Peel - Releasing the essential oils of a citrus fruit's peel to flavor cocktail Propely Stirred - For stirred cocktails served without ice, stir longer to properly chill and dilute. When served with ice, shorten stirring to avoid over dilution Simple Syrup - All recipes here refer to a 1:1 ratio for simple syrup or, equal parts sugar and water Egg Whites - Used in cocktails to create texture and presentation. -

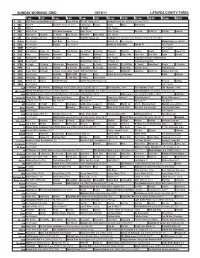

Sunday Morning Grid 10/16/11 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/16/11 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face/Nation The NFL Today (N) Å Football Buffalo Bills at New York Giants. (N) Å 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Conference George House House Gymnastics 5 CW News Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week-Amanpour News (N) Å News (N) Å News Å Vista L.A. IndyCar IndyCar 9 KCAL Tomorrow’s Kingdom K. Shook Joel Osteen Ministries Mike Webb Paid Program 11 FOX Hour of Power (N) (TVG) Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football 49ers at Detroit Lions. From Ford Field in Detroit. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Best Buys Paid Program Best of L.A. Paid Program Money Kings ›› (1998) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program Hecho en Guatemala Iranian TV Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Sid Science Curios -ity Thomas Bob Builder Joy of Paint Paint This Dewberry Wyland’s Cuisine Cook’s Kitchen Sweet Life 28 KCET Cons. Wubbulous Busytown Peep Pancakes Pufnstuf Lidsville Place, Own Chef Paul Burt Wolf Pepin Venetia 30 ION Turning Pnt. Discovery In Touch Paid Beyond Paid Program Inspiration Ministry Campmeeting 34 KMEX Paid Program Muchachitas Como Tu Al Punto (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN K. Hagin Ed Young Miracle-You Redemption Love In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Raymond Quentin Smuckles 7/2004 - 12/2008

RAYMOND QUENTIN SMUCKLES 7/2004 - 12/2008 ACHEWOOD Follow Ray Smuckles, in this 55,000-word supplement to his general intellectual methodologies, as he plans his Friday Parties, travels to Australia, mistakenly visits an Oriental hair loss specialist of the wrong variety, grouses about his lackluster sex life, and otherwise exhibits the proclivities of a man with a curious heart, a bottomless appetite, and far too much money. These collected blogs, tottled off in the wee hours during surprisingly common moments of reflection, describe a thoroughly modern creature with both traditional problems and cutting-edge weaknesses. Mr. Smuckles, a co-champion of the Great Outdoor Fight, has explored the depths and -scapes of all major forms of suffering, with the exception of parenthood and loss of a parent. Despite this, or perhaps because of this, or perhaps in order to set such wheels in motion, he can typically be found “blissed to the nines on bongo sauce and lifties,” usually in or near his room. —CTO 1 FRIDAY, JULY 02, 2004 I got to get rid of some Nagels Remember that famous artist from the 80s, "Nagel"? He did all kinds of what was considered at the time "great" art. Anyhow, I just found a bunch of my old Nagel prints down in the garage, stuff that I had on the walls back in my high school days. I need to have a garage sale. I could probably also get rid of those dumb fingerless gloves I bought at The Record Factory when I wanted to be like Julian Lennon.