Field Identification of Smaller Sandpipers Within the Genus <I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015)

IUCN Red List version 2015.4: Table 7 Last Updated: 19 November 2015 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2014 (IUCN Red List version 2014.3) and 2015 (IUCN Red List version 2015-4) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered, EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2014) List (2015) change version Category Category MAMMALS Aonyx capensis African Clawless Otter LC NT N 2015-2 Ailurus fulgens Red Panda VU EN N 2015-4 -

Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris Pusilla in Brazil: Occurrence Away from the Coast and a New Record for the Central-West Region

Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia 27(3): 218–221. SHORT-COMMUNICARTICLEATION September 2019 Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla in Brazil: occurrence away from the coast and a new record for the central-west region Karla Dayane de Lima Pereira1,3 & Jayrson Araújo de Oliveira2 1 Programa Integrado de Estudos da Fauna da Região Centro Oeste do Brasil (FaunaCO), Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 2 Departamento de Morfologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. 3 Corresponding author: [email protected] Received on 27 March 2019. Accepted on 16 September 2019. ABSTRACT: The Semipalmated Sandpiper, Calidris pusilla, is a Western Hemisphere migrant shorebird for which Brazil forms an internationally important contranuptial area. In Brazil, the species main contranuptial areas is along the Atlantic Ocean coast, in the north and northeast regions. In addition to these primary contranuptial areas, there are also records of vagrants widely distributed across Brazil. Here, we review the occurrence of vagrants of this species in Brazil, and document a new record of C. pusilla for the central-west region and a first occurrence for the state of Goiás. KEY-WORDS: geographical distribution, Nearctic migrant, shorebird, state of Goiás, vagrant. The Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla (Linnaeus, of Mato Grosso (Cintra 2011, Levatich & Padilha 2019) 1766) is a migratory shorebird species that breeds in and two in the municipality of Corumbá, state of Mato the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions of Alaska and Canada Grosso do Sul (Serrano 2010, Tubelis & Tomas 2003). (Andres et al. 2012, IUCN 2019). Every year, as the However, there is no evidence that these records have northern autumn approaches, Arctic populations fly been correctly identified, as individuals appear not to from 3000 to 4000 km to South America (Hicklin & have been collected and sent to a scientific collection, nor Gratto-Trevor 2010). -

Field Identification of Smaller Sandpipers Within the Genus <I

Field identification of smaller sandpipers within the genus C/dr/s Richard R. Veit and Lars Jonsson Paintings and line drawings by Lars Jonsson INTRODUCTION the hand, we recommend that the reader threeNearctic species, the Semipalmated refer to the speciesaccounts of Prateret Sandpiper (C. pusilia), the Western HESMALL Calidris sandpipers, affec- al. (1977) or Cramp and Simmons Sandpiper(C. mauri) andthe LeastSand- tionatelyreferred to as "peeps" in (1983). Our conclusionsin this paperare piper (C. minutilla), and four Palearctic North America, and as "stints" in Britain, basedupon our own extensivefield expe- species,the primarilywestern Little Stint haveprovided notoriously thorny identi- rience,which, betweenus, includesfirst- (C. minuta), the easternRufous-necked ficationproblems for many years. The hand familiarity with all sevenspecies. Stint (C. ruficollis), the eastern Long- first comprehensiveefforts to elucidate We also examined specimensin the toed Stint (C. subminuta)and the wide- thepicture were two paperspublished in AmericanMuseum of Natural History, spread Temminck's Stint (C. tem- Brtttsh Birds (Wallace 1974, 1979) in Museumof ComparativeZoology, Los minckii).Four of thesespecies, pusilla, whichthe problem was approached from Angeles County Museum, San Diego mauri, minuta and ruficollis, breed on the Britishperspective of distinguishing Natural History Museum, Louisiana arctictundra and are found during migra- vagrant Nearctic or eastern Palearctic State UniversityMuseum of Zoology, tion in flocksof up to thousandsof -

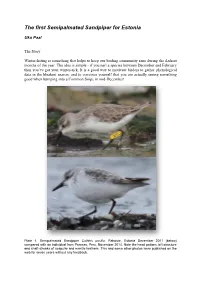

The First Semipalmated Sandpiper for Estonia

The first Semipalmated Sandpiper for Estonia Uku Paal The Story Winter-listing is something that helps to keep our birding community sane during the darkest months of the year. The idea is simple - if you nail a species between December and February then you’ve got your winter-tick. It is a good way to motivate birders to gather phenological data in the bleakest season, and to convince yourself that you are actually seeing something good when bumping into a Common Snipe in mid-December! Plate 1. Semipalmated Sandpiper Calidris pusilla. Rahuste, Estonia December 2011 (below) compared with an individual from Paracas, Peru, November 2014. Note the head pattern, bill structure and shaft-streaks of scapular and mantle feathers. This and some other photos were published on the web for seven years without any feedback. The late autumn of 2011 looked perfect to get some lingering migrants, as the warm weather was going strong well into January. In the first few days of December, I usually try to get to the west coast in the hope of some lost migrants, and so I packed myself off with Mari and Margus and headed to Saaremaa. Coastal meadows here are often hold a good selection of birds... We start at Türju lighthouse on the 3rd of December with a seawatching session. Nothing shocking this time with the usual Red-throated Divers, Razorbills, and a lone Red-necked Grebe passing. Rahuste coastal meadow is obviously the next site – a well-known place for getting some late birds. The situation looks exceptionally good. After trampling the area for couple of hours we manage to find White Wagtail, Skylark, five Common Snipe, two Pintail, 15 Lapwing, two Common Redshank, Grey Plover and Brant Goose among many other birds. -

<I>Actitis Hypoleucos</I>

Partial primary moult in first-spring/summer Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos M. NICOLL 1 & P. KEMP 2 •c/o DundeeMuseum, Dundee, Tayside, UK 243 LochinverCrescent, Dundee, Tayside, UK Citation: Nicoll, M. & Kemp, P. 1983. Partial primary moult in first-spring/summer Common Sandpipers Actitis hypoleucos. Wader Study Group Bull. 37: 37-38. This note is intended to draw the attention of wader catch- and the old inner feathersare often retained (Pearson 1974). ers to the needfor carefulexamination of the primariesof Similarly, in Zimbabwe, first-year Common Sandpipers CommonSandpipers Actiris hypoleucos,and other waders, replacethe outerfive to sevenprimaries between December for partial primarywing moult. This is thoughtto be a diag- andApril (Tree 1974). It thusseems normal for first-spring/ nosticfeature of wadersin their first spring and summer summerCommon Sandpipers wintering in eastand southern (Tree 1974). Africa to show a contrast between new outer and old inner While membersof the Tay Ringing Group were mist- primaries.There is no informationfor birdswintering further nettingin Angus,Scotland, during early May 1980,a Com- north.However, there may be differencesin moult strategy mon Sandpiperdied accidentally.This bird was examined betweenwintering areas,since 3 of 23 juvenile Common and measured, noted as an adult, and then stored frozen un- Sandpiperscaught during autumn in Morocco had well- til it was skinned,'sexed', andthe gut contentsremoved for advancedprimary moult (Pienkowski et al. 1976). These analysis.Only duringskinning did we noticethat the outer birdswere moultingnormally, and so may have completed primarieswere fresh and unworn in comparisonto the faded a full primary moult during their first winter (M.W. Pien- and abradedinner primaries.The moult on both wingswas kowski, pers.comm.). -

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide

Common Caribbean Shorebirds: ID Guide Large Medium Small 14”-18” 35 - 46 cm 8.5”-12” 22 - 31 cm 6”- 8” 15 - 20 cm Large Shorebirds Medium Shorebirds Small Shorebirds Whimbrel 17.5” 44.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs 9.5” 24 cm Wilson’s Plover 7.75” 19.5 cm Spotted Sandpiper 7.5” 19 cm American Oystercatcher 17.5” 44.5 cm Black-bellied Plover 11.5” 29 cm Sanderling 7.75” 19.5 cm Western Sandpiper 6.5” 16.5 cm Willet 15” 38 cm Short-billed Dowitcher 11” 28 cm White-rumped Sandpiper 6” 15 cm Greater Yellowlegs 14” 35.5 cm Ruddy Turnstone 9.5” 24 cm Semipalmated Sandpiper 6.25” 16 cm 6.25” 16 cm American Avocet* 18” 46 cm Red Knot 10.5” 26.5 cm Snowy Plover Least Sandpiper 6” 15 cm 14” 35.5 cm 8.5” 21.5 cm Semipalmated Plover Black-necked Stilt* Pectoral Sandpiper 7.25” 18.5 cm Killdeer* 10.5” 26.5 cm Piping Plover 7.25” 18.5 cm Stilt Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm Lesser Yellowlegs & Ruddy Turnstone: Brad Winn; Red Knot: Anthony Levesque; Pectoral Sandpiper & *not pictured Solitary Sandpiper* 8.5” 21.5 cm White-rumped Sandpiper: Nick Dorian; All other photos: Walker Golder Clues to help identify shorebirds Size & Shape Bill Length & Shape Foraging Behavior Size Length Sandpipers How big is it compared to other birds? Peeps (Semipalmated, Western, Least) Walk or run with the head down, picking and probing Spotted Sandpiper Short Medium As long Longer as head than head Bobs tail up and down when walking Plovers, Turnstone or standing Small Medium Large Sandpipers White-rumped Sandpiper Tail tips up while probing Yellowlegs Overall Body Shape Stilt Sandpiper Whimbrel, Oystercatcher, Probes mud like “oil derrick,” Willet, rear end tips up Dowitcher, Curvature Plovers Stilt, Avocet Run & stop, pick, hiccup, run & stop Elongate Compact Yellowlegs Specific Body Parts Stroll and pick Bill & leg color Straight Upturned Dowitchers Eye size Plovers = larger, sandpipers = smaller Tip slightly Probe mud with “sewing machine” Leg & neck length downcurved Downcurved bill, body stays horizontal . -

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List

Draft Version Target Shorebird Species List The target species list (species to be surveyed) should not change over the course of the study, therefore determining the target species list is an important project design task. Because waterbirds, including shorebirds, can occur in very high numbers in a census area, it is often not possible to count all species without compromising the quality of the survey data. For the basic shorebird census program (protocol 1), we recommend counting all shorebirds (sub-Order Charadrii), all raptors (hawks, falcons, owls, etc.), Common Ravens, and American Crows. This list of species is available on our field data forms, which can be downloaded from this site, and as a drop-down list on our online data entry form. If a very rare species occurs on a shorebird area survey, the species will need to be submitted with good documentation as a narrative note with the survey data. Project goals that could preclude counting all species include surveys designed to search for color-marked birds or post- breeding season counts of age-classed bird to obtain age ratios for a species. When conducting a census, you should identify as many of the shorebirds as possible to species; sometimes, however, this is not possible. For example, dowitchers often cannot be separated under censuses conditions, and at a distance or under poor lighting, it may not be possible to distinguish some species such as small Calidris sandpipers. We have provided codes for species combinations that commonly are reported on censuses. Combined codes are still species-specific and you should use the code that provides as much information as possible about the potential species combination you designate. -

Purple Sandpiper

Maine 2015 Wildlife Action Plan Revision Report Date: January 13, 2016 Calidris maritima (Purple Sandpiper) Priority 1 Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN) Class: Aves (Birds) Order: Charadriiformes (Plovers, Sandpipers, And Allies) Family: Scolopacidae (Curlews, Dowitchers, Godwits, Knots, Phalaropes, Sandpipers, Snipe, Yellowlegs, And Woodcock) General comments: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). Maine has high responsibility for wintering population, regional surveys suggest Maine may support over 1/3 of the Western Atlantic wintering population. USFWS Region 5 and Canadian Maritimes winter at least 90% of the Western Atlantic population. Species Conservation Range Maps for Purple Sandpiper: Town Map: Calidris maritima_Towns.pdf Subwatershed Map: Calidris maritima_HUC12.pdf SGCN Priority Ranking - Designation Criteria: Risk of Extirpation: NA State Special Concern or NMFS Species of Concern: NA Recent Significant Declines: Purple Sandpiper is currently undergoing steep population declines, which has already led to, or if unchecked is likely to lead to, local extinction and/or range contraction. Notes: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). Maine has high responsibility for wintering populat Regional Endemic: Calidris maritima's global geographic range is at least 90% contained within the area defined by USFWS Region 5, the Canadian Maritime Provinces, and southeastern Quebec (south of the St. Lawrence River). Notes: Recent surveys suggest population undergoing steep population decline within 10 years. IFW surveys conducted in 2014 suggest population declined by 49% since 2004 (IFW unpublished data). -

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with Birds Observed Off-Campus During BIOL3400 Field Course

Birds of the East Texas Baptist University Campus with birds observed off-campus during BIOL3400 Field course Photo Credit: Talton Cooper Species Descriptions and Photos by students of BIOL3400 Edited by Troy A. Ladine Photo Credit: Kenneth Anding Links to Tables, Figures, and Species accounts for birds observed during May-term course or winter bird counts. Figure 1. Location of Environmental Studies Area Table. 1. Number of species and number of days observing birds during the field course from 2005 to 2016 and annual statistics. Table 2. Compilation of species observed during May 2005 - 2016 on campus and off-campus. Table 3. Number of days, by year, species have been observed on the campus of ETBU. Table 4. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during the off-campus trips. Table 5. Number of days, by year, species have been observed during a winter count of birds on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Table 6. Species observed from 1 September to 1 October 2009 on the Environmental Studies Area of ETBU. Alphabetical Listing of Birds with authors of accounts and photographers . A Acadian Flycatcher B Anhinga B Belted Kingfisher Alder Flycatcher Bald Eagle Travis W. Sammons American Bittern Shane Kelehan Bewick's Wren Lynlea Hansen Rusty Collier Black Phoebe American Coot Leslie Fletcher Black-throated Blue Warbler Jordan Bartlett Jovana Nieto Jacob Stone American Crow Baltimore Oriole Black Vulture Zane Gruznina Pete Fitzsimmons Jeremy Alexander Darius Roberts George Plumlee Blair Brown Rachel Hastie Janae Wineland Brent Lewis American Goldfinch Barn Swallow Keely Schlabs Kathleen Santanello Katy Gifford Black-and-white Warbler Matthew Armendarez Jordan Brewer Sheridan A. -

Biogeographical Profiles of Shorebird Migration in Midcontinental North America

U.S. Geological Survey Biological Resources Division Technical Report Series Information and Biological Science Reports ISSN 1081-292X Technology Reports ISSN 1081-2911 Papers published in this series record the significant find These reports are intended for the publication of book ings resulting from USGS/BRD-sponsored and cospon length-monographs; synthesis documents; compilations sored research programs. They may include extensive data of conference and workshop papers; important planning or theoretical analyses. These papers are the in-house coun and reference materials such as strategic plans, standard terpart to peer-reviewed journal articles, but with less strin operating procedures, protocols, handbooks, and manu gent restrictions on length, tables, or raw data, for example. als; and data compilations such as tables and bibliogra We encourage authors to publish their fmdings in the most phies. Papers in this series are held to the same peer-review appropriate journal possible. However, the Biological Sci and high quality standards as their journal counterparts. ence Reports represent an outlet in which BRD authors may publish papers that are difficult to publish elsewhere due to the formatting and length restrictions of journals. At the same time, papers in this series are held to the same peer-review and high quality standards as their journal counterparts. To purchase this report, contact the National Technical Information Service, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, VA 22161 (call toll free 1-800-553-684 7), or the Defense Technical Infonnation Center, 8725 Kingman Rd., Suite 0944, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060-6218. Biogeographical files o Shorebird Migration · Midcontinental Biological Science USGS/BRD/BSR--2000-0003 December 1 By Susan K. -

List of Shorebird Profiles

List of Shorebird Profiles Pacific Central Atlantic Species Page Flyway Flyway Flyway American Oystercatcher (Haematopus palliatus) •513 American Avocet (Recurvirostra americana) •••499 Black-bellied Plover (Pluvialis squatarola) •488 Black-necked Stilt (Himantopus mexicanus) •••501 Black Oystercatcher (Haematopus bachmani)•490 Buff-breasted Sandpiper (Tryngites subruficollis) •511 Dowitcher (Limnodromus spp.)•••485 Dunlin (Calidris alpina)•••483 Hudsonian Godwit (Limosa haemestica)••475 Killdeer (Charadrius vociferus)•••492 Long-billed Curlew (Numenius americanus) ••503 Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa)••505 Pacific Golden-Plover (Pluvialis fulva) •497 Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa)••473 Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres)•••479 Sanderling (Calidris alba)•••477 Snowy Plover (Charadrius alexandrinus)••494 Spotted Sandpiper (Actitis macularia)•••507 Upland Sandpiper (Bartramia longicauda)•509 Western Sandpiper (Calidris mauri) •••481 Wilson’s Phalarope (Phalaropus tricolor) ••515 All illustrations in these profiles are copyrighted © George C. West, and used with permission. To view his work go to http://www.birchwoodstudio.com. S H O R E B I R D S M 472 I Explore the World with Shorebirds! S A T R ER G S RO CHOOLS P Red Knot (Calidris canutus) Description The Red Knot is a chunky, medium sized shorebird that measures about 10 inches from bill to tail. When in its breeding plumage, the edges of its head and the underside of its neck and belly are orangish. The bird’s upper body is streaked a dark brown. It has a brownish gray tail and yellow green legs and feet. In the winter, the Red Knot carries a plain, grayish plumage that has very few distinctive features. Call Its call is a low, two-note whistle that sometimes includes a churring “knot” sound that is what inspired its name. -

Ageing and Sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis Hypoleucos

ageing & sexing series Wader Study 122(1): 54 –59. 10.18194/ws.00009 This series summarizing current knowledge on ageing and sexing waders is co-ordinated by Włodzimier Meissner (Avian Ecophysiology Unit, Department of Vertebrate Ecology & Zoology, University of Gdansk, ul. Wita Stwosza 59, 80-308 Gdansk, Poland, [email protected]). See Wader Study Group Bulletin vol. 113 p. 28 for the Introduction to the series. Part 11: Ageing and sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos Włodzimierz Meissner 1, Philip K. Holland 2 & Tomasz Cofta 3 1Avian Ecophysiology Unit, Department of Vertebrate Ecology & Zoology, University of Gdańsk, ul.Wita Stwosza 59, 80-308 Gdańsk, Poland. [email protected] 232 Southlands, East Grinstead, RH19 4BZ, UK. [email protected] 3Hoene 5A/5, 80-041 Gdańsk, Poland. [email protected] Meissner, W., P.K. Holland & T. Coa. 2015. Ageing and sexing series 11: Ageing and sexing the Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos . Wader Study 122(1): 54 –59. Keywords: Common Sandpiper, Actitis hypoleucos , ageing, sexing, moult, plumages The Common Sandpiper Actitis hypoleucos is treated as were validated using about 500 photographs available on monotypic through a breeding range that extends from the Internet and about 50 from WRG KULING ringing Ireland eastwards to Japan. Its main non-breeding area is sites in northern Poland. also vast, reaching from the Canary Islands to Australia with a few also in the British Isles, France, Spain, Portugal MOULT SCHEDULE and the Mediterranean (Cramp & Simmons 1983, del Juveniles and adults leave the breeding grounds as soon Hoyo et al. 1996, Glutz von Blotzheim et al.