Covid-19 in Areas of Kurdish Self Administration Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ar-Raqqa Governorate, April 2018 OVERALL FINDINGS1

Ar-Raqqa Governorate, April 2018 Humanitarian Situation Overview in Syria (HSOS) OVERALL FINDINGS1 Coverage Ar-Raqqa governorate is located in northeast Syria. The Euphrates River flows through the governorate TURKEY and into the Al-Thawrah Dam, the largest hydroelectric dam providing electricity in Syria, although years of Tell Abiad conflict have limited its ability to generate electricity. Since the conflict over Ar-Raqqa city ended in October AL-HASAKEH 2017, electricity services have been mostly unavailable. However, recent repairs to the Al Furosya electric ALEPPO station resulted in 72% of the assessed communities relying primarily on the electricity network in April. Ein Issa Suluk In over half of assessed communities, Key Informants (KIs) estimated that 76-100% of the pre-conflict population remained. However, 7 communities in Ar- Raqqa and Ein Issa sub-districts, reported less than 50% of pre-conflict populations remained. The majority of the assessed communities reported a presence of IDPs, approximately 90,037 IDPs in total. Most of these IDPs resided in Al-Thawra community, which has experienced two large IDP influxes in the past four months. In April, approximately 25 spontaneous Ar-Raqqa refugee returns from Lebanon and Jordan were reported in Jurneyyeh community (Ath-Thawrah district). Jurneyyeh The most commonly reported reasons for return were to reunite with family and protection concerns in host Karama communities2. Ar-Raqqa KIs reported that healthcare was one of the top priority needs in April. Reflective of this, 25 of the Al-Thawrah assessed communities reported that there were no health facilities available in the area, and only 3 of the Maadan assessed communities reported having functioning pre-conflict hospitals. -

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Spontaneous Returns December 2020 IDP (Wos) Task Force

SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC IDP Spontaneous Returns December 2020 IDP (WoS) Task Force December 2020 updates Governorate summary In December 2020, the humanitarian community recorded some 13,400 spontaneous IDP 4K Aleppo 4K return movements across Syria. Over 7,000 of these (54 percent) occurred within and 5K between Aleppo and Idleb governorates. 4K At the sub-district level, Jebel Saman in Aleppo governorate received the highest number of Idleb 3K 3K spontaneous return movements in December, with around 2,200 returns, while Khan Shaykun in Idleb governorate and Ar-Raqqa in Ar-Raqqa governorate respectively received 2K Hama 1K some 1,200 and 1,100 spontaneous IDP return movements. More than 700 spontaneous IDP 3K return movements were received by Al-Thawrah sub-district in Ar-Raqqa governorate over 2K the same period. Ar-Raqqa 533 533 At the community level, Aleppo city in Aleppo governorate received the most return 90 movements in December, recording around 2,100 returns. Khan Shaykun community in Al-Hasakeh 40 71% 1K Idleb governorate and Ar-Raqqa city in Ar-Raqqa governorate respectively received some of IDP spontaneous 1,200 and 1,100 spontaneous IDP return movements. Al-Thawrah town in Ar-Raqqa 666 returnee arrıvals governorate received some 700 return movements, while Homs town in Homs governorate Homs 416 416 occurred within received some 500 return movements. governorate 315 Notes: Deir-ez-Zor 85 - The returns refer to IDP spontaneous returns and do not necessarily follow the global 85 definitions of ‘Returnees’ or durable solutions for IDPs. 0 Damascus - The IDP spontaneous returns include IDPs returning to their homes or communities of 0 IDPs return to governorate 277 n origin. -

Ar Raqqa Governorate

“THIS IS MORE THAN VIOLENCE”: AN OVERVIEW OF CHILDREN’S PROTECTION NEEDS IN SYRIA Ar Raqqa PROTECTION SEVERITY RANKING BY SUB-DISTRICT Severity ranking by sub-districts considered Tell Abiad 3 indicators: i) % of IDPs in the population; Al-Hasakeh Ein Issa Suluk ii) conflict incidents weighted according to the extent of impact; and Aleppo Ar-Raqqa iii) population in hard-to-reach communities. Jurneyyeh Ar-Raqqa Karama Sve anks Al-Thawrah Maadan N oblem oblem Sabka Mansura Deir-ez-Zor Moderat oblem oblem Svere oblem Cri�cal problem Homs Catrastrophic problem POPULATION DATA Number of 0-4 Years 5-14 Years 15-17 Years Locations Total Children % of Children Total Population Communities 336 Overall Population 9% 25% 8% 184K 42% 440K PIN 10% 25% 8% 166K 43% 384K IDP 9% 25% 8% 65K 42% 157K Hard to Reach Locations 184 9% 25% 8% 103K 42% 248K Besieged Locations 0 Military Encircled Locations 1 9% 25% 8% 6K 42% 13K * es�mates to support humanitarian planning processes only SUMMARY OF FINDINGS 313 communities (93%) were assessed in Ar-Raqqa governorate. population groups. • In 74 per cent of assessed communities, respondents • In 70 percent of assessed communities respondents reported child labour preventing school attendance was an issue reported that family violence was an issue of concern. Both of concern. Both adolescent boys and adolescent girls were adolescent boys and adolescent girls were considered considered equally affected (72%). equalled affected (66%). • In 85 per cent of assessed communities, respondents reported • In 97 per cent of assessed communities, respondents child recruitment was an issue of concern. -

Syria Protection Sectors

Main Implementing Partner COVID-19 SITUATION ANALYSIS FIRST ANNUAL REVIEW - LIVELIHOODS, FOOD SECURITY, AGRICULTURE AND SYRIA PROTECTION SECTORS. July 2020 - July 2021 Better Data Better Decisions Better Outcomes The outbreak of disease caused by the virus known as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV-2) or COVID-19 started in China in December 2019. The virus quickly spread across the world, with the WHO Director-General declaring it as a pandemic on March 11th, 2020. The virus’s impact has been felt most acutely by countries facing humanitarian crises due to conflict and natural disasters. As humanitarian access to vulnerable communities has been restricted to basic movements only, monitoring and assessments have been interrupted. To overcome these constraints and provide the wider humanitarian community with timely and comprehensive information on the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, iMMAP initiated the COVID-19 Situational Analysis project with the support of the USAID Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance (USAID BHA), aiming to provide timely solutions to the growing global needs for assessment and analysis among humanitarian stakeholders. CONTENTS 1. Introduction Page4 A. About this report 4 2. COVID-19 Overview Page5 3. Containment measures Page22 4. Displacement Page28 5. Economic overview Page29 Livelihood 34 Food security 48 Agriculture 65 Protection 68 6. Methodology and review of data Page75 Better Data Better Decisions Better Outcomes 3 // 79 INTRODUCTION About this report Food, livelihoods, WASH, education and protection needs This report reviews the data collected between July 2020 were significantly exacerbated in Syria by the economic and July 2021 and highlights the main issues and evolution consequences of COVID-19 related restrictions. -

Syria Crisis: Ar-Raqqa Situation Report No. 4 (As of 1 May 2017 )

Syria Crisis: Ar-Raqqa Situation Report No. 4 (as of 1 May 2017 ) This report is produced by the OCHA Syria Crisis offices in Syria, Turkey and Jordan. It covers the period from 1 to 30 April 2017 and also informs on the humanitarian response to IDPs displaced from Ar-Raqqa to neighbouring governorates. The next report will be issued in mid-May. Highlights Displacement in Ar-Raqqa Governorate intensifies as the fourth phase of the Euphrates Wrath operation begins. Civilian deaths and damage to civilian infrastructure continues unabated due to ongoing hostilities and intensified airstrikes. Water supply gradually returns to the governorate, following the opening of some flood gates of Tabqa Dam. Reports of increased shortages of food and medical supplies in Ar- Raqqa city continue to be received. 66,275 221,600 1,000+ 800-1000m3 individuals people reached with tents were set up litres of potable water displaced in April 2017 food assistance during April in various IDP supplied daily across camps and transit various IDP camps and sites transit sites Situation Overview During the reporting period, fighting between the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) continued unabated, resulting in scores of civilian casualties and large displacement movements, contributing to the overall deterioration of the humanitarian situation across the governorate. Fighting and airstrikes intensified over the course of the month. In the first part of the month, airstrikes and increased shelling occurred in several locations (Ar-Raqqa city, Kasret Faraj towns, Atabaqa city and its suburbs), reportedly killing scores of people. -

Hidden Battlefields

HIDDEN BATTLEFIELDS: REHABILITATING ISIS AFFILIATES AND BUILDING A DEMOCRATIC CULTURE IN THEIR FORMER TERRITORIES DECEMBER 2020 HIDDEN BATTLEFIELDS: REHABILITATING ISIS AFFILIATES AND BUILDING A DEMOCRATIC CULTURE IN THEIR FORMER TERRITORIES DECEMBER 2020 CONTENTS ABSTRACT 04 — 05 DEFINITIONS AND METHODOLOGY 06 — 07 AUTHORS 07 1. INTRODUCTION 08 — 12 1.1 TERRITORIAL DEFEAT OF ISIS 08 1.2 DETENTION FACILITIES 08 1.3 DEFUSING THE TIME-BOMB: THE NEED FOR REHABILITATION 11 2. ISIS’ LEGACY IN NORTH AND EAST SYRIA (NES) 12 — 22 2.1. ISIS’ IDEOLOGY IN NES 12 — 16 2.1.1 THEOLOGICAL, POLITICAL AND SOCIAL ASPECTS 12 2.1.2 INDOCTRINATION METHODS UNDER ISIS 14 2.1.3 IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION PROGRAMS 16 FACTBOX: DETENTION CENTERS HOLDING ISIS AFFILIATES IN NES: AN OVERVIEW 17 — 19 2.2 NON-IDEOLOGICAL MOTIVES FOR JOINING ISIS 19 — 21 2.2.1 IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION PROGRAMS 21 — 22 3. NES’ POLITICAL FRAMEWORK AND THE POLITICS OF AMNESTIES 22 — 30 3.1 DEMOCRACY, DECENTRALIZATION AND SECULARISM IN NES 22 — 23 3.2 JUSTICE REFORM IN NES 24 3.3 EDUCATION AND WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT IN NES 25 3.4 RELOCATIONS, RETURNS AND AMNESTIES 25 — 30 3.4.1 AMNESTY FOR HOL CAMP RESIDENTS AND ISIS PRISONERS 26 — 27 3.4.2 TRANSFERS FROM AND EXPANSION OF HOL CAMP 28 3.4.3 AMNESTIES AND TRANSFERS IN THE CONTEXT OF 29 — 30 REHABILITATION AND REFORM 2 HIDDEN BATTLEFIELDS: REHABILITATING ISIS AFFILIATES AND BUILDING A DEMOCRATIC CULTURE IN THEIR FORMER TERRITORIES DECEMBER 2020 CONTENTS 4. REHABILITATION INITIATIVES IN DETENTION FACILITIES AND BEYOND 30 — 45 4.1 REHABILITATING -

Situation Report: WHO Syria, Week 19-20, 2019

WHO Syria: SITUATION REPORT Weeks 28 – 29 (5 – 18 July), 2019 I. General Development, Political and Security Situation (22 June - 4July), 2019 The security situation within the country remains volatile and unstable. The main hot spots remain Daraa, Al- Hassakah, Deir Ezzor, Latakia, Hama, Aleppo and Idlib governorates. The Turkish military preparations along the Syrian /Turkish borders escalated the tension in the Euphrates region ushering in an imminent military operation against the Kurds. The Eastern governorates are still witnessing a high level of asymmetric attacks against SDF personnel in the form of of IEDs and VBIEDs explosions. The security situation in North rural Hama remained tense; SAA regained control over a town that was seized by NSAGs a week ago . Military operations are still taking place against NSAGs held towns in Idlib, Hama, Latakia and Aleppo Governorates. An increase in the number of Indirect Artillery Fire attack (AIF) has been noted in Aleppo city in comparison with the previous week. At least five Syrian soldiers were killed after being attacked in the governorate of Daraa, 90 km south of the capital Damascus. Military sources asserted that the terrorists ambushed a military vehicle between Yadouda and Dahya, leaving five soldiers dead and 16 injured. Air strikes targeted rebel-held cities in northwest Syria on Friday, a war monitor reported, widening bombardment of the last major insurgent enclave to areas that had mostly escaped it. The strikes killed three people in Idlib and three in Maarat al-Numan, two of the largest cities in the region, the Britain-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said according to a Reuters report. -

Isis: the Political History of the Messianic Violent Non-State Actor in Syria

2016 T.C. YILDIRIM BEYAZIT UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DISSERTATION ISIS: THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF THE MESSIANIC VIOLENT NON-STATE ACTOR IN SYRIA PhD Dissertation Ufuk Ulutaş Ufuk Ulutaş PhD INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Ankara, 2016 ISIS: THE POLITICAL HISTORY OF THE MESSIANIC VIOLENT NON-STATE ACTOR IN SYRIA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF YILDIRIM BEYAZIT UNIVERSITY BY UFUK ULUTAŞ IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILISOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS AUGUST 2016 2 Approval of the Institute of Social Sciences Yrd.Doç. SeyfullahYıldırım Manager of Institute I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr.Birol Akgün Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Birol Akgün Prof. Muhittin Ataman Supervisor Co-Supervisor Examining CommitteeMembers Prof. Dr. Birol Akgün YBÜ, IR Prof. Dr. Muhittin Ataman YBÜ, IR Doç Dr. Mehmet Şahin Gazi, IR Prof. Dr. Erdal Karagöl YBÜ, Econ Dr. Nihat Ali Özcan TOBB, IR 3 I hereby declare that all information in this thesis has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work; otherwise I accept all legal responsibility. Ufuk Ulutaş i To my mom, ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There is a long list of people to thank who offered their invaluable assistance and insights on ISIS. -

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 6 - 12 April 2020

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 6 - 12 April 2020 SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST | Levels of conflict in northwest Syria remained elevated for the third consecutive week. The Turkish military continued to shell areas around northern Aleppo Governorate. In Turkish-held areas of Aleppo, opposition armed groups engaged in intragroup clashes over property and smuggling disputes. Government of Syria (GoS)-backed forces clashed with opposition armed groups but made no advances. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | The Islamic State of Iraq and al Sham (ISIS) launched attacks on GoS positions in the east of Homs Governorate. GoS-aligned personnel and officials continued to be targeted in Dara’a Governorate. • NORTHEAST | The SDF imposed new security measures to combat the spread of COVID-19. Landmines and remote-controlled explosions killed 10 people in the Euphrates River Valley. ISIS attacked GoS positions in Deir- ez-Zor. Figure 1: Dominant actors’ area of control and influence in Syria as of 12 April 2020. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. Also, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 5 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 6 – 12 April 2020 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 For the third consecutive week, there were elevated levels of conflict activity in the northwest of Syria. The Government of Syria (GoS) shelled 17 locations, 28 times around the Hayyat Tahrir al Sham-dominated enclave. Most of the shelling exchanges took place in Idlib Governorate, with 3 exchanges in Lattakia Governorate, and 4 in Aleppo Governorate.2 (Figure 2) GoS shelling exchanges on 6 and 7 April hit the perimeter of a Turkish observation post in Sarmin, Idlib. -

Covid-19 Situation Analysis Syria Crisis Type: Epidemic March 2021

Main Implementing Partner COVID-19 SITUATION ANALYSIS SYRIA CRISIS TYPE: EPIDEMIC MARCH 2021 Better Data Better Decisions Better Outcomes The outbreak of disease caused by the virus known as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV-2) or COVID-19 started in China in December 2019. The virus quickly spread across the world, with the WHO Director-General declaring it as a pandemic on March 11th, 2020. The virus’s impact has been felt most acutely by countries facing humanitarian crises due to conflict and natural disasters. As humanitarian access to vulnerable communities has been restricted to basic movements only, monitoring and assessments have been interrupted. To overcome these constraints and provide the wider humanitarian community with timely and comprehensive information on the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, iMMAP initiated the COVID-19 Situational Analysis project with the support of the USAID Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance (USAID BHA), aiming to provide timely solutions to the growing global needs for assessment and analysis among humanitarian stakeholders. CONTENTS 1. COVID-19 and containment measures overview Page 4 A. COVID-19 Overview B. Containment Measures 10 C. Preventative Measures 13 2. Drivers and humanitarian consequences Page 18 D. Drivers 18 E. Displacement 22 F. COVID-19 Related Humanitarian Consequences 23 Health 23 Livelihoods 30 Food Security 34 Nutrition 39 Education 40 Protection 44 WASH 47 Shelter 51 Logistics 52 3. Information gaps: what are we missing? Page 54 Better Data Better Decisions Better -

WFP Syria Situation Report #4

WFP Syria Situation Report #4 April 2017 Highlights In Numbers WFP dispatched food assistance for 3.8 million people; 29 percent of the assistance was delivered to areas not 13.5 m people in need of humani- regularly reachable from inside Syria through cross-border, tarian assistance cross-line and air deliveries. 6.3 m people internally displaced WFP provided urgent food assistance for 216,100 newly displaced people in Idleb, Ar-Raqqa, Aleppo, Deir Ezzor 9 m people in need of food assis- and Dar’a governorate. tance WFP’s Executive Director (ED), David Beasley, made an official visit to Syria on 1-2 May. This was the first visit of the newly appointed ED to WFP operations since he assumed office in April. 55% 45% 3.8 million people Situation Update assisted April 2017 Evacuation of People from the Four Towns In early April, the Government of Syria and armed PRRO 200988 groups agreed to evacuate the Four Towns of Foah and Kefraya in Idleb governorate (under government control) and Madaya and Zabadani in Rural Damascus Global Overall: governorate (under opposition control). An estimated USD 3,407,792,269 Humanitarian WFP share: 11,800 people from the towns were evacuated to Funding USD 797,579,193 government controlled areas and areas under opposition control, respectively. These towns were WFP 6-month Net Funding besieged for more than three years, and people have been living under very difficult and constrained Requirements (May—Oct 2017) conditions with limited access and availability of sufficient food items. The food and nutrition needs PRRO 200988 USD 257 million* among the evacuees are high, particularly among women, children and elderly people. -

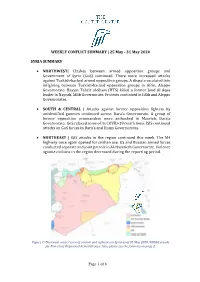

Page 1 of 6 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 25

WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 25 May - 31 May 2020 SYRIA SUMMARY • NORTHWEST| Clashes between armed opposition groups and Government of Syria (GoS) continued. There were increased attacks against Turkish-backed armed opposition groups. A dispute escalated into infighting between Turkish-backed opposition groups in Afrin, Aleppo Governorate. Hayyat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) killed a former Jund Al Aqsa leader in Nayrab, Idlib Governorate. Protests continued in Idlib and Aleppo Governorates. • SOUTH & CENTRAL | Attacks against former opposition fighters by unidentified gunmen continued across Dara’a Governorate. A group of former opposition commanders were ambushed in Mzerieb, Dara’a Governorate. GoS relaxed some of its COVID-19 restrictions. ISIS continued attacks on GoS forces in Dara’a and Homs Governorates. • NORTHEAST | ISIS attacks in the region continued this week. The M4 highway once again opened for civilian use. US and Russian armed forces conducted separate and joint patrols in Al-Hassakah Governorate. Violence against civilians in the region decreased during the reporting period. Figure 1: Dominant actors’ area of control and influence in Syria as of 31 May 2020. NSOAG stands for Non-state Organized Armed Groups. Also, please see the footnote on page 2. Page 1 of 6 WEEKLY CONFLICT SUMMARY | 25 May – 31 May 2020 NORTHWEST SYRIA1 Clashes between armed opposition groups and GoS armed forces continued this week. On 27 May, GoS forces and opposition groups clashed in the Taqad area in western Aleppo Governorate. On 28 May, opposition groups repelled a GoS armed forces attack in the towns of Ftireh and Fleifel in southern Idlib Governorate. The next day in Ftireh, HTS clashed with GoS armed forces and GoS-backed militias,2 with both sides engaging in an artillery exchange.