Chapter 6. Mathematics and Numbers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

End-Of-Line Hyphenation of Chemical Names (IUPAC Provisional

Pure Appl. Chem. 2020; aop IUPAC Recommendations Albert J. Dijkstra*, Karl-Heinz Hellwich, Richard M. Hartshorn, Jan Reedijk and Erik Szabó End-of-line hyphenation of chemical names (IUPAC Provisional Recommendations) https://doi.org/10.1515/pac-2019-1005 Received October 16, 2019; accepted January 21, 2020 Abstract: Chemical names and in particular systematic chemical names can be so long that, when a manu- script is printed, they have to be hyphenated/divided at the end of a line. Many systematic names already contain hyphens, but sometimes not in a suitable division position. In some cases, using these hyphens as end-of-line divisions can lead to illogical divisions in print, as can also happen when hyphens are added arbi- trarily without considering the ‘chemical’ context. The present document provides recommendations and guidelines for authors of chemical manuscripts, their publishers and editors, on where to divide chemical names at the end of a line and instructions on how to avoid these names being divided at illogical places as often suggested by desk dictionaries. Instead, readability and chemical sense should prevail when authors insert optional hyphens. Accordingly, the software used to convert electronic manuscripts to print can now be programmed to avoid illogical end-of-line hyphenation and thereby save the author much time and annoy- ance when proofreading. The recommendations also allow readers of the printed article to determine which end-of-line hyphens are an integral part of the name and should not be deleted when ‘undividing’ the name. These recommendations may also prove useful in languages other than English. -

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database File:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-Tr44-3D1.Html

UAX #44: Unicode Character Database file:///D:/Uniweb-L2/Incoming/08249-tr44-3d1.html Technical Reports L2/08-249 Working Draft for Proposed Update Unicode Standard Annex #44 UNICODE CHARACTER DATABASE Version Unicode 5.2 draft 1 Authors Mark Davis ([email protected]) and Ken Whistler ([email protected]) Date 2008-7-03 This Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-3.html Previous http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/tr44-2.html Version Latest Version http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr44/ Revision 3 Summary This annex consolidates information documenting the Unicode Character Database. Status This is a draft document which may be updated, replaced, or superseded by other documents at any time. Publication does not imply endorsement by the Unicode Consortium. This is not a stable document; it is inappropriate to cite this document as other than a work in progress. A Unicode Standard Annex (UAX) forms an integral part of the Unicode Standard, but is published online as a separate document. The Unicode Standard may require conformance to normative content in a Unicode Standard Annex, if so specified in the Conformance chapter of that version of the Unicode Standard. The version number of a UAX document corresponds to the version of the Unicode Standard of which it forms a part. Please submit corrigenda and other comments with the online reporting form [Feedback]. Related information that is useful in understanding this annex is found in Unicode Standard Annex #41, “Common References for Unicode Standard Annexes.” For the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see [Unicode]. For a list of current Unicode Technical Reports, see [Reports]. -

Perfect-Fluid Cylinders and Walls-Sources for the Levi-Civita

Perfect-fluid cylinders and walls—sources for the Levi–Civita space–time Thomas G. Philbin∗ School of Mathematics, Trinity College, Dublin 2, Ireland Abstract The diagonal metric tensor whose components are functions of one spatial coordinate is considered. Einstein’s field equations for a perfect-fluid source are reduced to quadratures once a generating function, equal to the product of two of the metric components, is chosen. The solutions are either static fluid cylinders or walls depending on whether or not one of the spatial coordinates is periodic. Cylinder and wall sources are generated and matched to the vacuum (Levi– Civita) space–time. A match to a cylinder source is achieved for 1 <σ< 1 , − 2 2 where σ is the mass per unit length in the Newtonian limit σ 0, and a match → to a wall source is possible for σ > 1 , this case being without a Newtonian | | 2 limit; the positive (negative) values of σ correspond to a positive (negative) fluid density. The range of σ for which a source has previously been matched to the Levi–Civita metric is 0 σ< 1 for a cylinder source. ≤ 2 1 Introduction arXiv:gr-qc/9512029v2 7 Feb 1996 Although a large number of vacuum solutions of Einstein’s equations are known, the physical interpretation of many (if not most) of them remains unsettled (see, e.g., [1]). As stressed by Bonnor [1], the key to physical interpretation is to ascertain the nature of the sources which produce these vacuum space–times; even in black-hole solutions, where no matter source is needed, an understanding of how a matter distribution gives rise to the black-hole space–time is necessary to judge the physical significance (or lack of it) of the complete analytic extensions of these solutions. -

Learning Language Pack Availability Company

ADMINISTRATION GUIDE | PUBLIC Document Version: Q4 2019 – 2019-11-08 Learning Language Pack Availability company. All rights reserved. All rights company. affiliate THE BEST RUN 2019 SAP SE or an SAP SE or an SAP SAP 2019 © Content 1 What's New for Learning Language Pack Availability....................................3 2 Introduction to Learning Language Support...........................................4 3 Adding a New Locale in SAP SuccessFactors Learning...................................5 3.1 Locales in SAP SuccessFactors Learning................................................6 3.2 SAP SuccessFactors Learning Locales Summary..........................................6 3.3 Activating Learning Currencies...................................................... 7 3.4 Setting Users' Learning Locale Preferences..............................................8 3.5 SAP SuccessFactors Learning Time and Number Patterns in Locales........................... 9 Editing Hints to Help SAP SuccessFactors Learning Users with Date, Time, and Number Patterns ......................................................................... 10 Adding Learning Number Format Patterns........................................... 11 Adding Learning Date Format Patterns..............................................12 3.6 Updating Language Packs.........................................................13 3.7 Editing User Interface Labels - Best Practice............................................ 14 4 SAP SuccessFactors LearningLearner Languages......................................15 -

About the Course • an Introduction and 61 Lessons Review Proper Posture and Hand Position, Home Row Placement, and the Concepts Taught in Typing 1 and 2

About the Course • An introduction and 61 lessons review proper posture and hand position, home row placement, and the concepts taught in Typing 1 and 2. The lessons also increase typing speed and teach the following typing skills: all numbers; tab key; colon, slash, parentheses, symbols, and plus and minus signs; indenting and centering; and capitalization and punctuation rules. • This course uses beautifully designed pages with images of nature for those who are looking for an inexpensive, effective, fun, offline program with a “good and beautiful” feel. The course supports high moral character and gives fun practice—all without the need for flashy and over-stimulating effects that often come with on-screen computer programs. • This course is designed for children who have completed The Good & the Beautiful Typing 2 course or have had the same level of typing experience. Items Needed • Course book and sticker sheet • A laptop or computer with a basic word processing program, such as Word, Pages, or Google Docs • Easel document holder (for standing the course book next to the computer) How the Course Works • The child should complete 1 or more lessons a day, 2–5 days a week. (Lessons take 5–15 minutes, depending on the speed of the child.) The child checks off the shell check box each time a lesson is completed. • To complete a lesson, the child places the course book on an easel document holder next to the laptop or computer and follows the instructions, typing assignments in a basic word processing program. • When a page is completed, the child chooses a sticker and places it on the page where indicated. -

The Stata Journal

The Stata Journal View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Editor Executive Editor provided by Research Papers in Economics H. Joseph Newton Nicholas J. Cox Department of Statistics Department of Geography Texas A & M University University of Durham College Station, Texas 77843 South Road 979-845-3142; FAX 979-845-3144 Durham City DH1 3LE UK [email protected] [email protected] Associate Editors Christopher Baum J. Scott Long Boston College Indiana University Rino Bellocco Thomas Lumley Karolinska Institutet University of Washington, Seattle David Clayton Roger Newson Cambridge Inst. for Medical Research King’s College, London Mario A. Cleves Marcello Pagano Univ. of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Harvard School of Public Health Charles Franklin Sophia Rabe-Hesketh University of Wisconsin, Madison University of California, Berkeley Joanne M. Garrett J. Patrick Royston University of North Carolina MRC Clinical Trials Unit, London Allan Gregory Philip Ryan Queen’s University University of Adelaide James Hardin Mark E. Schaffer University of South Carolina Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh Stephen Jenkins Jeroen Weesie University of Essex Utrecht University Jens Lauritsen Jeffrey Wooldridge Odense University Hospital Michigan State University Stanley Lemeshow Ohio State University Stata Press Production Manager Lisa Gilmore Copyright Statement: The Stata Journal and the contents of the supporting files (programs, datasets, and help files) are copyright c by StataCorp LP. The contents of the supporting files (programs, datasets, and help files) may be copied or reproduced by any means whatsoever, in whole or in part, as long as any copy or reproduction includes attribution to both (1) the author and (2) the Stata Journal. -

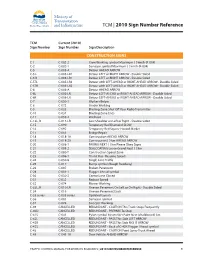

2010 Sign Number Reference for Traffic Control Manual

TCM | 2010 Sign Number Reference TCM Current (2010) Sign Number Sign Number Sign Description CONSTRUCTION SIGNS C-1 C-002-2 Crew Working symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-2 C-002-1 Surveyor symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-5 C-005-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-5 L C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5 R C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5TL C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-5TR C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6 C-006-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-6L C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6R C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-7 C-050-1 Workers Below C-8 C-072 Grader Working C-9 C-033 Blasting Zone Shut Off Your Radio Transmitter C-10 C-034 Blasting Zone Ends C-11 C-059-2 Washout C-13L, R C-013-LR Low Shoulder on Left or Right - Double Sided C-15 C-090 Temporary Red Diamond SLOW C-16 C-092 Temporary Red Square Hazard Marker C-17 C-051 Bridge Repair C-18 C-018-1A Construction AHEAD ARROW C-19 C-018-2A Construction ( ) km AHEAD ARROW C-20 C-008-1 PAVING NEXT ( ) km Please Obey Signs C-21 C-008-2 SEALCOATING Loose Gravel Next ( ) km C-22 C-080-T Construction Speed Zone C-23 C-086-1 Thank You - Resume Speed C-24 C-030-8 Single Lane Traffic C-25 C-017 Bump symbol (Rough Roadway) C-26 C-007 Broken Pavement C-28 C-001-1 Flagger Ahead symbol C-30 C-030-2 Centre Lane Closed C-31 C-032 Reduce Speed C-32 C-074 Mower Working C-33L, R C-010-LR Uneven Pavement On Left or On Right - Double Sided C-34 -

THE DIMENSION of a VECTOR SPACE 1. Introduction This Handout

THE DIMENSION OF A VECTOR SPACE KEITH CONRAD 1. Introduction This handout is a supplementary discussion leading up to the definition of dimension of a vector space and some of its properties. We start by defining the span of a finite set of vectors and linear independence of a finite set of vectors, which are combined to define the all-important concept of a basis. Definition 1.1. Let V be a vector space over a field F . For any finite subset fv1; : : : ; vng of V , its span is the set of all of its linear combinations: Span(v1; : : : ; vn) = fc1v1 + ··· + cnvn : ci 2 F g: Example 1.2. In F 3, Span((1; 0; 0); (0; 1; 0)) is the xy-plane in F 3. Example 1.3. If v is a single vector in V then Span(v) = fcv : c 2 F g = F v is the set of scalar multiples of v, which for nonzero v should be thought of geometrically as a line (through the origin, since it includes 0 · v = 0). Since sums of linear combinations are linear combinations and the scalar multiple of a linear combination is a linear combination, Span(v1; : : : ; vn) is a subspace of V . It may not be all of V , of course. Definition 1.4. If fv1; : : : ; vng satisfies Span(fv1; : : : ; vng) = V , that is, if every vector in V is a linear combination from fv1; : : : ; vng, then we say this set spans V or it is a spanning set for V . Example 1.5. In F 2, the set f(1; 0); (0; 1); (1; 1)g is a spanning set of F 2. -

Glossary of Linear Algebra Terms

INNER PRODUCT SPACES AND THE GRAM-SCHMIDT PROCESS A. HAVENS 1. The Dot Product and Orthogonality 1.1. Review of the Dot Product. We first recall the notion of the dot product, which gives us a familiar example of an inner product structure on the real vector spaces Rn. This product is connected to the Euclidean geometry of Rn, via lengths and angles measured in Rn. Later, we will introduce inner product spaces in general, and use their structure to define general notions of length and angle on other vector spaces. Definition 1.1. The dot product of real n-vectors in the Euclidean vector space Rn is the scalar product · : Rn × Rn ! R given by the rule n n ! n X X X (u; v) = uiei; viei 7! uivi : i=1 i=1 i n Here BS := (e1;:::; en) is the standard basis of R . With respect to our conventions on basis and matrix multiplication, we may also express the dot product as the matrix-vector product 2 3 v1 6 7 t î ó 6 . 7 u v = u1 : : : un 6 . 7 : 4 5 vn It is a good exercise to verify the following proposition. Proposition 1.1. Let u; v; w 2 Rn be any real n-vectors, and s; t 2 R be any scalars. The Euclidean dot product (u; v) 7! u · v satisfies the following properties. (i:) The dot product is symmetric: u · v = v · u. (ii:) The dot product is bilinear: • (su) · v = s(u · v) = u · (sv), • (u + v) · w = u · w + v · w. -

MTH 304: General Topology Semester 2, 2017-2018

MTH 304: General Topology Semester 2, 2017-2018 Dr. Prahlad Vaidyanathan Contents I. Continuous Functions3 1. First Definitions................................3 2. Open Sets...................................4 3. Continuity by Open Sets...........................6 II. Topological Spaces8 1. Definition and Examples...........................8 2. Metric Spaces................................. 11 3. Basis for a topology.............................. 16 4. The Product Topology on X × Y ...................... 18 Q 5. The Product Topology on Xα ....................... 20 6. Closed Sets.................................. 22 7. Continuous Functions............................. 27 8. The Quotient Topology............................ 30 III.Properties of Topological Spaces 36 1. The Hausdorff property............................ 36 2. Connectedness................................. 37 3. Path Connectedness............................. 41 4. Local Connectedness............................. 44 5. Compactness................................. 46 6. Compact Subsets of Rn ............................ 50 7. Continuous Functions on Compact Sets................... 52 8. Compactness in Metric Spaces........................ 56 9. Local Compactness.............................. 59 IV.Separation Axioms 62 1. Regular Spaces................................ 62 2. Normal Spaces................................ 64 3. Tietze's extension Theorem......................... 67 4. Urysohn Metrization Theorem........................ 71 5. Imbedding of Manifolds.......................... -

The Not So Short Introduction to Latex2ε

The Not So Short Introduction to LATEX 2ε Or LATEX 2ε in 139 minutes by Tobias Oetiker Hubert Partl, Irene Hyna and Elisabeth Schlegl Version 4.20, May 31, 2006 ii Copyright ©1995-2005 Tobias Oetiker and Contributers. All rights reserved. This document is free; you can redistribute it and/or modify it under the terms of the GNU General Public License as published by the Free Software Foundation; either version 2 of the License, or (at your option) any later version. This document is distributed in the hope that it will be useful, but WITHOUT ANY WARRANTY; without even the implied warranty of MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. See the GNU General Public License for more details. You should have received a copy of the GNU General Public License along with this document; if not, write to the Free Software Foundation, Inc., 675 Mass Ave, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA. Thank you! Much of the material used in this introduction comes from an Austrian introduction to LATEX 2.09 written in German by: Hubert Partl <[email protected]> Zentraler Informatikdienst der Universität für Bodenkultur Wien Irene Hyna <[email protected]> Bundesministerium für Wissenschaft und Forschung Wien Elisabeth Schlegl <noemail> in Graz If you are interested in the German document, you can find a version updated for LATEX 2ε by Jörg Knappen at CTAN:/tex-archive/info/lshort/german iv Thank you! The following individuals helped with corrections, suggestions and material to improve this paper. They put in a big effort to help me get this document into its present shape. -

General Topology

General Topology Tom Leinster 2014{15 Contents A Topological spaces2 A1 Review of metric spaces.......................2 A2 The definition of topological space.................8 A3 Metrics versus topologies....................... 13 A4 Continuous maps........................... 17 A5 When are two spaces homeomorphic?................ 22 A6 Topological properties........................ 26 A7 Bases................................. 28 A8 Closure and interior......................... 31 A9 Subspaces (new spaces from old, 1)................. 35 A10 Products (new spaces from old, 2)................. 39 A11 Quotients (new spaces from old, 3)................. 43 A12 Review of ChapterA......................... 48 B Compactness 51 B1 The definition of compactness.................... 51 B2 Closed bounded intervals are compact............... 55 B3 Compactness and subspaces..................... 56 B4 Compactness and products..................... 58 B5 The compact subsets of Rn ..................... 59 B6 Compactness and quotients (and images)............. 61 B7 Compact metric spaces........................ 64 C Connectedness 68 C1 The definition of connectedness................... 68 C2 Connected subsets of the real line.................. 72 C3 Path-connectedness.......................... 76 C4 Connected-components and path-components........... 80 1 Chapter A Topological spaces A1 Review of metric spaces For the lecture of Thursday, 18 September 2014 Almost everything in this section should have been covered in Honours Analysis, with the possible exception of some of the examples. For that reason, this lecture is longer than usual. Definition A1.1 Let X be a set. A metric on X is a function d: X × X ! [0; 1) with the following three properties: • d(x; y) = 0 () x = y, for x; y 2 X; • d(x; y) + d(y; z) ≥ d(x; z) for all x; y; z 2 X (triangle inequality); • d(x; y) = d(y; x) for all x; y 2 X (symmetry).