The Netflix Effect: Examining the Influence of Contemporary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

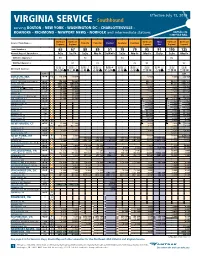

Amtrak Timetables-Virginia Service

Effective July 13, 2019 VIRGINIA SERVICE - Southbound serving BOSTON - NEW YORK - WASHINGTON DC - CHARLOTTESVILLE - ROANOKE - RICHMOND - NEWPORT NEWS - NORFOLK and intermediate stations Amtrak.com 1-800-USA-RAIL Northeast Northeast Northeast Silver Northeast Northeast Service/Train Name4 Palmetto Palmetto Cardinal Carolinian Carolinian Regional Regional Regional Star Regional Regional Train Number4 65 67 89 89 51 79 79 95 91 195 125 Normal Days of Operation4 FrSa Su-Th SaSu Mo-Fr SuWeFr SaSu Mo-Fr Mo-Fr Daily SaSu Mo-Fr Will Also Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 Will Not Operate4 9/1 9/2 9/2 9/2 9/2 R B y R B y R B y R B y R B s R B y R B y R B R s y R B R B On Board Service4 Q l å O Q l å O l å O l å O r l å O l å O l å O y Q å l å O y Q å y Q å Symbol 6 R95 BOSTON, MA ∑w- Dp l9 30P l9 30P 6 10A 6 30A 86 10A –South Station Boston, MA–Back Bay Station ∑v- R9 36P R9 36P R6 15A R6 35A 8R6 15A Route 128, MA ∑w- lR9 50P lR9 50P R6 25A R6 46A 8R6 25A Providence, RI ∑w- l10 22P l10 22P 6 50A 7 11A 86 50A Kingston, RI (b(™, i(¶) ∑w- 10 48P 10 48P 7 11A 7 32A 87 11A Westerly, RI >w- 11 05P 11 05P 7 25A 7 47A 87 25A Mystic, CT > 11 17P 11 17P New London, CT (Casino b) ∑v- 11 31P 11 31P 7 45A 8 08A 87 45A Old Saybrook, CT ∑w- 11 53P 11 53P 8 04A 8 27A 88 04A Springfield, MA ∑v- 7 05A 7 25A 7 05A Windsor Locks, CT > 7 24A 7 44A 7 24A Windsor, CT > 7 29A 7 49A 7 29A Train 495 Train 495 Hartford, CT ∑v- 7 39A Train 405 7 59A 7 39A Berlin, CT >v D7 49A 8 10A D7 49A Meriden, CT >v D7 58A 8 19A D7 58A Wallingford, CT > D8 06A 8 27A D8 06A State Street, CT > q 8 19A 8 40A 8 19A New Haven, CT ∑v- Ar q q 8 27A 8 47A 8 27A NEW HAVEN, CT ∑v- Ar 12 30A 12 30A 4 8 41A 4 9 03A 4 88 41A Dp l12 50A l12 50A 8 43A 9 05A 88 43A Bridgeport, CT >w- 9 29A Stamford, CT ∑w- 1 36A 1 36A 9 30A 9 59A 89 30A New Rochelle, NY >w- q 10 21A NEW YORK, NY ∑w- Ar 2 30A 2 30A 10 22A 10 51A 810 22A –Penn Station Dp l3 00A l3 25A l6 02A l5 51A l6 45A l7 17A l7 25A 10 35A l11 02A 11 05A 11 35A Newark, NJ ∑w- 3 20A 3 45A lR6 19A lR6 08A lR7 05A lR7 39A lR7 44A 10 53A lR11 22A 11 23A 11 52A Newark Liberty Intl. -

Actor Russell Tovey Gets Personal About His Art Collection

Embuscado, Rain. Actor Russell Tovey Gets Personal About His Art Collection. Artnet news. October 11, 2016. Actor Russell Tovey Gets Personal About His Art Collection He’s his artists’ biggest champion. By Rain Embuscado Celebrity Collectors is a series that explores the fascinating and mysterious world of high-profile art collections. Fans may recognize Russell Tovey as the beleaguered werewolf in BBC’s Being Human, Patrick’s love interest in HBO’s Looking, or, more recently, as the enigmatic new character on ABC’s runaway hit Quantico. But what may be lesser-known about the actor is his off-screen relationship with contemporary art—a serious passion he regularly touts on Instagram. I last saw Tovey on the fair circuit during this year’s Armory Show, where he was standing in front of an enormous contour drawing by legendary Young British Artist Tracey Emin at Carolina Nitsch‘s booth. These days, Tovey told me, he’s been on the gallery crawl in New York whenever he has a spare moment, making the occasional studio visit along the way. In a recent phone conversation, we talked about the artists he’s been interested in, the importance of collecting, and how he got into art. “As a kid I always connected to pop art through cartoons and comic books like Tintin and Marvel, and then discovering Keith Haring, Roy Lichtenstein, and Andy Warhol,” he said. “I loved advertising art and people like Mel Ramos using that in his work, but I never realized that you could actually buy into art and live with it.” Tell us how you got into art. -

Distances Between United States Ports 2019 (13Th) Edition

Distances Between United States Ports 2019 (13th) Edition T OF EN CO M M T M R E A R P C E E D U N A I C T I E R D E S M T A ATES OF U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) RDML Timothy Gallaudet., Ph.D., USN Ret., Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere and Acting Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere National Ocean Service Nicole R. LeBoeuf, Deputy Assistant Administrator for Ocean Services and Coastal Zone Management Cover image courtesy of Megan Greenaway—Great Salt Pond, Block Island, RI III Preface Distances Between United States Ports is published by the Office of Coast Survey, National Ocean Service (NOS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), pursuant to the Act of 6 August 1947 (33 U.S.C. 883a and b), and the Act of 22 October 1968 (44 U.S.C. 1310). Distances Between United States Ports contains distances from a port of the United States to other ports in the United States, and from a port in the Great Lakes in the United States to Canadian ports in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River. Distances Between Ports, Publication 151, is published by National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and distributed by NOS. NGA Pub. 151 is international in scope and lists distances from foreign port to foreign port and from foreign port to major U.S. ports. The two publications, Distances Between United States Ports and Distances Between Ports, complement each other. -

17-20 October 2016

17-20 October 2016 Cannes, France Press Release KIEFER SUTHERLAND AWARD-WINNING ACTOR AND EXECUTIVE PRODUCER GIVES MIPCOM MEDIA MASTERMIND KEYNOTE Paris, 22 September 2016 – Kiefer Sutherland, Award-winning actor and executive producer, will deliver the Media Mastermind Keynote on Monday October 17th at 4:40pm in the Grand Auditorium at MIPCOM 2016. Kiefer Sutherland is an Emmy and Golden Globe award-winning actor who starred in the groundbreaking Fox drama series “24” as special agent, Jack Bauer. He will next be seen starring in “Designated Survivor” from The Mark Gordon Company and ABC Studios, distributed internationally by eOne. “Designated Survivor” is a conspiracy thriller and family drama about an ordinary man in an extraordinary situation. The series follows a lower level United States Cabinet member, Tom Kirkman (Kiefer Sutherland), who is suddenly appointed President after a catastrophic attack during the State of the Union kills everyone above him in the Presidential line of succession. Featuring a stellar cast including Natascha McElhone (Californication) as Kirkman’s wife, an equal employment opportunity attorney, Maggie Q (Nikita) as Hannah, the lead FBI agent on the bombing of the Capitol, Kal Penn (House) as Kirkman’s speech writer, Adan Canto (Narcos) as his senior advisor, and Italia Ricci (Chasing Life) as his no-nonsense Chief of Staff Emily, the series is from The Mark Gordon Company (Grey’s Anatomy, Ray Donovan, Quantico, Criminal Minds) and ABC Studios, and created by David Guggenheim (Safe House, Bad Boys 3), who executive produces with Simon Kinberg (The Martian, X- Men), Kiefer Sutherland, Mark Gordon (Grey’s Anatomy), Nick Pepper (Quantico), Suzan Bymel and Aditya Sood, alongside showrunner Jon Feldman (Dirty Sexy Money). -

Sonakshi Sinha to Eyewitness Accounts, “As Soon Says That Just Like Peter Pan, His So Personal?” She Asked

14 Saturday, October 3, 2015 Saturday, October 3, 2015 15 Success is only meaningful and enjoyable if it feels like your own. -Michelle Obama New York iley Cyrus is getting ready to host the season premiere of Saturday Night LiveM this weekend, so to prepare, she and Jimmy Fallon decided to put her acting Manhattan skills on display during her visit to The eira Knightley was all set to make her highly Tonight Show Thursday. Kanticipated Broadway debut Thursday night Los Angeles Even though we’ll never forget her role on in the opening preview performance of Helen ugh Jackman stars Hannah Montana, despite brutally killing her Edmundson’s Thérèse Raquin in the titular Has Blackbeard in his off on a previous episode of SNL, Fallon just role. But, unlike the standard theatre new movie Pan, but wanted to make sure she had the chops to mantra, practice doesn’t always make it turns out the actor take on the live stage, so he tested her with an perfect. might have more in emotional interview. Only minutes after the common with the Lost It all began with a prompt that required curtains’ draw, the show Boys than the villainous her to become super defensive. Asking her was disrupted by an unruly pirate. whether she preferred acting or singing, the audience member who began Opening up about his late-night talk show host received a hostile shouting concerning phrases at painful childhood in a candid answer. the Oscar nominee. According interview with Parade, Jackman “Jesus Christ, Jimmy, do you have to get Sonakshi Sinha to eyewitness accounts, “As soon says that just like Peter Pan, his so personal?” she asked. -

Estado De New York | Executive Chamber Andrew M. Cuomo | Gobernador

Para su publicación inmediata: GOBERNADOR ANDREW M. CUOMO 22/04/2016 Estado de New York | Executive Chamber Andrew M. Cuomo | Gobernador ANUNCIAN EL GOBERNADOR CUOMO Y ABC STUDIOS QUE LA TEMPORADA DOS DE LA SERIE DE TELEVISIÓN QUANTICO SE FILMARÁ EN NEW YORK Quantico generará cientos de empleos y millones de dólares durante su producción El Gobernador Andrew M. Cuomo y ABC Studios (una subsidiaria de T he Walt Disney Company ) anunciaron hoy que la exitosa serie de televisión Quantico dejará Montreal y se mudará a New York. La próxima temporada incluirá 22 episodios de una hora, creando cientos de empleos locales y generando alrededor de $68 millones de gasto en el Estado de New York. Todos los aspectos de la producción, incluyendo al equipo de guionistas, se localizarán en New York. La filmación debe comenzar en julio y creará al menos 300 empleos de tiempo completo en el estado de New York, y la postproducción continuará hasta mayo de 2017. La postproducción de la primera temporada de Quantico se realizó en New York y aportó $5 millones a la economía local “El Estado de New York no tiene límites en lo creativo y ofrece una oportunidad inigualable de trabajar con los mejores de la industria”, dijo el Gobernador Cuomo. “Nos enorgullece que Disney reconozca todo lo que New York tiene para ofrecer, y que la reubicación de Quantico generará cientos de empleos para neoyorquinos y aportará millones de dólares a empresas locales”. El presidente, director general y comisionado de Empire State Development Howard Zemsky dijo, “Estamos muy emocionados de que el elenco y los trabajadores de la exitosa serie Quantico filmen en New York. -

Federal Resources on Missing and Exploited Children Rolodex

U.S. Department of Defense U.S. Department of Defense Army Family Advocacy Program Air Force Family Advocacy Program Army Family Advocacy Program Air Force Family Advocacy Program Army Family Advocacy Program Manager Chief, Family Advocacy Division HQDA, CFSC–FPA HQ AFMSA/SGOF Department of the Army 2664 Flight Nurse Road, Building 801 4700 King Street, Fourth Floor Brooks City Base, TX 78235–5254 Alexandria, VA 22302–4418 Phone: 703–681–7393 Phone: 210–536–2031 Fax: 703–681–7239 Fax: 210–536–9032 U.S. Department of Defense U.S. Department of Defense Navy Family Advocacy Program Marine Corps Family Advocacy Program Navy Family Advocacy Program Marine Corps Family Advocacy Program Fleet & Family Support Programs Marine Corps Family Advocacy Program Manager Personnel Support Department (N2) Marine & Family Services Branch Commander, Navy Installations (CNI) Headquarters USMC 2713 Mitscher Road SW., Suite 300 3280 Russell Road Anacostia Annex, DC 20373–5802 Quantico, VA 22134–5009 Phone: 202–433–4593 Phone: 703–784–9546 Fax: 202–433–0481 Fax: 703–784–9825 U.S. Department of Defense U.S. Department of Defense Army Legal Assistance Air Force Legal Assistance Army Legal Assistance Air Force Legal Assistance Legal Assistance Policy Division Air Force Legal Services Agency Office of the Judge Advocate General AFLSA/JACA 1777 North Kent Street, Ninth Floor 1420 Air Force Pentagon, Room 5C263 Arlington, VA 22209 Washington, DC 20330–1420 Phone: 703–588–6708 Phone: 202–697–0413 U.S. Department of Defense U.S. Department of Defense Navy Legal Assistance Marine Corps Legal Assistance Navy Legal Assistance Marine Corps Legal Assistance Naval Legal Assistance Command Commandant of the Marine Corps Department of the Navy Headquarters, USMC (Code JAL) 1322 Patterson Street SE., Suite 3000 3000 Marine Corps Pentagon Washington Navy Yard Washington, DC 20350–3000 Washington, DC 20374–5016 Phone: 703–614–1266 Phone: 202–685–5190 U.S. -

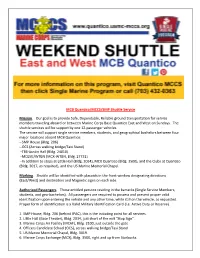

MCB Quantico/MCCS/SMP Shuttle Service Mission. Our Goal Is To

MCB Quantico/MCCS/SMP Shuttle Service Mission. Our goal is to provide Safe, Dependable, Reliable ground transportation for service members traveling aboard or between Marine Corps Base Quantico East and West on Sundays. The shuttle services will be support by one 12-passenger vehicles. The service will support single service members, students, and geographical bachelors between four major locations aboard MCB Quantico: --SMP House (Bldg. 206) --OCS (Across walking bridge/Taxi Stand) --TBS-Austin Hall (Bldg. 24010) --MCESG/WTBN (MCX-WTBN, Bldg. 27731) --In addition to stops at Little Hall (Bldg. 2034), MCX Quantico (Bldg. 3500), and the Clubs at Quantico (Bldg. 3017, as required), and the US Marine Memorial Chapel. Marking. Shuttle will be identified with placards in the front window designating directions (East/West) and destination and Magnetic signs on each side. Authorized Passengers. Those entitled persons residing in the barracks (Single Service Members, students, and geo-bachelors). All passengers are required to possess and present proper valid identification upon entering the vehicle and any other time, while still on the vehicle, as requested. Proper form of identification is a Valid Military Identification Card (i.e. Active Duty or Reserve). 1. SMP House, Bldg. 206 (behind IPAC), this is the initiating point for all services. 2. Little Hall (Base Theater), Bldg. 2034, just short of the exit “Stop Sign”. 3. Marine Corps Air Facility (MCAF), Bldg. 2100, just outside the gate. 4. Officers Candidate School (OCS), across walking bridge/Taxi Stand. 5. US Marine Memorial Chapel, Bldg. 3019. 6. Marine Corps Exchange (MCX), Bldg. 3500, right and up from Starbucks. -

TRENTON BOOKS, AUDIOBOOKS, and DVD Available in Donovan

MCoE HQ Donovan Research Library http://www.benning.army.mil/library/ TRENTON BOOKS, AUDIOBOOKS, and DVD available in Donovan Library BOOKS E181 .B883 1999 Brooks, Victor and Robert Hohwald. How America Fought its Wars: Military Strategy from the American Revolution to the Civil War. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Pub., 1999: 50-60. Print. E208 .A433 1993 v.2 Sanborn, Paul J. “Trenton, New Jersey, Battle of (December 26, 1776).” / American Revolution 1775-1783: an Encyclopedia, The. Vol. 2. Ed. Richard L. Blanco. New York: Garland Publishing, 1993: 1650-9. Print. E230 .D82 1970 Dupuy, Trevor Nevitt. Military History of Revolutionary War Land Battles. New York: Franklin Watts, 1970: 38-49. Print. E230 .M69 M5 1962 Mitchell, Joseph B. Decisive Battles of the American Revolution. New York: / G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1962: 74-80. Print. E230 .S435 2006 Savas, Theodore P. and J. David Dameron. Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution, A. New York: Savas Beatie, 2006: 81-7. Print. E230 .W66 1990 Wood, W.J. Wood. Battles of the Revolutionary War. Chapel Hill, NC: / Algonquin Books, 1990: 55-91. Print. E232 .B5 1948 Bill, Alfred Hoyt. Campaign of Princeton, 1776-1777, The. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1948: 25-44. Print. Archives. E241 .T7 S6 1965 Smith, Samuel Stelle. Battle of Trenton, The. Monmouth Beach, NJ: Philip Freneau Press, 1965. Print. E241 .T7 E98 1898 Stryker, William S. Battles of Trenton and Princeton, The. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, and Co., 1898. Print. Archives. E259 .K47 1973 Ketchum, Richard M. Winter Soldiers, The. New York: Doubleday, 1973: 269-321. Print. -

Replace Quantico Middle High School

+ REPLACE QUANTICO MIDDLE HIGH SCHOOL Marine Corps Base, Quantico, VA National Capital Planning Commission Project Narrative EWINGCOLE PROJECT NUMBER: 20130353 July 3, 2014 The sponsoring agency for this project is the Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Washington District, Marine Corps Base, Quantico, VA acting for the project proponent. P.O.C.’s for these organizations are as follows: Naval Facilities Engineering Command, Washington District 1314 Harwood St. SE Washington Navy Yard, DC 20374-5018 Installation Project Lead Sam Nouri: 202-685-8463 NAVFAC Liaison to NCPC This Project Report has been prepared for the Replace Middle High School project at Marine Corps Base, Quantico, VA. This report has been prepared for submission to the National Capital Planning Commission for their review and approval. Federal Reserve Bank Building, 100 North 6th Street, Philadelphia, PA 19106 TEL 215.923.2020 FAX 215.574.9163 ewingcole.com PROJECT DESCRIPTION 1.1 PROJECT BACKGROUND The existing Middle High School facilities were constructed in 1960 and have a poor condition rating. Existing classroom and education spaces are undersized and have inadequate infrastructure that fails to meet the standards of the current DoDEA Education Specifications. Aging utility infrastructure systems result in excessive maintenance costs. Most infrastructure components, such as HVAC, electrical and plumbing, have exceeded their useful life. The roof system is failing and there are numerous leaks that cause damage to the interior of the facility. There are numerous NFPA Life Safety and ADA code deficiencies, no fire suppression systems, and poor indoor air quality. The facilities do not meet construction standards for energy efficiency. Numerous maintenance and repair problems have developed and are becoming non- repairable. -

Wikileaking the Truth About American Unaccountability for Torture Lisa Hajjar University of California—Santa Barbara

Societies Without Borders Volume 7 | Issue 2 Article 3 2012 Wikileaking the Truth about American Unaccountability for Torture Lisa Hajjar University of California—Santa Barbara Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/swb Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Hajjar, Lisa. 2012. "Wikileaking the Truth about American Unaccountability for Torture." Societies Without Borders 7 (2): 192-225. Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/swb/vol7/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Cross Disciplinary Publications at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Societies Without Borders by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Hajjar: Wikileaking the Truth about American Unaccountability for Torture L. Hajjar/Societies Without Borders 7:2 (2012) 192-225 Wikileaking the Truth about American Unaccountability for Torture Lisa Hajjar University of California—Santa Barbara Received September 2011; Accepted March 2012 ______________________________________________________ Abstract. Grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions are international offenses and perpetrators can be prosecuted abroad if accountability is not pursued at home. The US torture policy, instituted by the Bush administration in the context of the “war on terror” presents a contemporary example of liability for gross crimes under international law. For this reason, classification and secrecy have functioned in tandem as a shield to block public knowledge about prosecutable offenses. Keeping such information secret and publicizing deceptive official accounts that contradict the truth are essential to propaganda strategies to sustain American support or apathy about the country’s multiple current wars. -

QUANTICO Network Draft 011415 Unstarred

QUANTICO "Pilot" Joshua Safran REVISED NETWORK DRAFT 01.14.15 ©2015, ABC Studios. All rights reserved. This material is the exclusive property of ABC Studios and is intended solely for the use of its personnel. Distribution to unauthorized persons or reproduction, in whole or in part, without the written consent of ABC Studios is strictly prohibited. CLOSE ON: RUBBLE The marble hand of a decimated sculpture lays next to the unmoving human hand of ALEX WEAVER, 25, lying on a pile of rubble. Through the smoke rising from several fires nearby, we can’t tell where we are. But it doesn’t look good... EXT. OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA - DAY Nine months earlier. The fresher face of beautiful, haunted Alex enters the screen. She runs alongside the bay in Oakland, pushing herself hard. EXT. WEAVER HOUSE - OAKLAND - DAY She runs up to the front of a modest house and heads inside. INT. WEAVER HOUSE - DAY Alex moves down the hall to her bedroom. Her mother, CYNTHIA, a weary 50, peeks out from the living room where she’s watching television and smoking. CYNTHIA You’re going to be late! INT. WEAVER HOUSE - ALEX’S CHILDHOOD BEDROOM - CONTINUOUS Alex sits down on her childhood bed, kicks her running shoes over to two packed suitcases on the floor. Cynthia appears. CYNTHIA I printed your ticket, it’s on the dresser. Want me to pack some food? ALEX Thanks, Mom. I’m just gonna shower. Something catches Alex’s eye: a loose edge of the wall-to- wall carpet by the closet. As Cynthia exits, Alex gets down on the floor, lifts up the carpet edge.