Progressive Growth, CAP’S Economic Plan for the Next Administration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EPA Administrator Lisa P. Jackson Schedule

Release 4 - HQ-FOI-01268-12 All emails sent by "Richard Windsor" were sent by EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson 01268-EPA-5928 Noah Dubin/DC/USEPA/US To 01/26/2012 06:15 PM cc bcc Richard Windsor Subject 01/30/2012 thru 02/12/2012 Schedule for Lisa P. Jackson *** Do not copy or forward this information *** EPA Administrator Lisa P. Jackson Schedule 01/26/2012 06:11:57 PM Monday, 1/30/2012 08:45 AM-09:15 AM Daily Briefing Location: Administrator's Office ------------------------------- 09:30 AM-10:30 AM HOLD: WH POST-SOTU Ct: Ryan Robison - 202-564-2856 Location: Administrator's Office ------------------------------- 10:30 AM-11:00 AM Personnel Discussion Ct:Ryan Robison - 202-564-2856 Staff: Diane Thompson, Jose Lozano (OA) Paul Anastas (ORD) Optional: Bob Perciasepe (OA) Location: Administrator's Office ------------------------------- 11:00 AM-09:00 PM Out of Office See EA or Jose Location: NYC ------------------------------- 01:00 PM-02:00 PM FYI: Senior Staff Location: Bullet Room ------------------------------- Tuesday, 1/31/2012 09:30 AM-10:30 AM HOLD: WH POST-SOTU Ct: Ryan Robison - 202-564-2856 Location: Administrator's Office ------------------------------- 10:30 AM-10:45 AM Depart for White House Location: Ariel Rios ------------------------------- 10:45 AM-12:15 PM Cabinet Meeting Ct: Liz Ashwell 564.1008 Full Cabinet Meeting w/ POTUS and VPOTUS Location: Cabinet Room, White House ------------------------------- 12:15 PM-12:30 PM Depart for Ariel Rios Release 4 - HQ-FOI-01268-12 All emails sent by "Richard Windsor" were sent by EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson Location: White House ------------------------------- 12:45 PM-12:50 PM Drop-By Meeting with Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission Ct: Earl Comstock - 202-255-0273 **AA DePass will be lead on this meeting, the Administrator will drop by if her schedule permits **This meeting will last from 12:45 to 1:15 -Mr. -

363 Steve Davison of World Wide Travel Also Remembered Thomason Citing Mrs

Lady."363 Steve Davison of World Wide Travel also remembered Thomason citing Mrs. Clinton's views on the Travel Office.364 D. The Events of April -- May 1993. In late April 1993, Thomason returned to Washington. His return coincided with Cornelius's discovery of fiscal mishandling of the Travel Office cash accounts. As a result, beginning in mid-May, senior White House officials devoted substantial attention to the Travel Office. From May 12 through May 19, 1993, more than a dozen meetings occurred; the White House through Associate White House Counsel William Kennedy called in the Federal Bureau of Investigation ("FBI") to conduct a criminal investigation; and the accounting firm of Peat Marwick was hired to audit the Travel Office's books. In the end, on May 19, 1993, the seven White House Travel Office employees were summarily dismissed. 1. In Late April or Early May, Thomason Returned to Washington and Once Again Raised the Issue of Illegality in the Travel Office With Watkins. On April 29, 1993, Thomason flew to Washington with Markie Post-Ross, a television actress and friend of Thomason's, to attend the White House Correspondents’ Association Dinner.365 Ms. Post-Ross said that during their trip Thomason told her he was concerned that his 363 Cerda GJ 7/1/96 at 161, 168. 364 Todd Stern's White House Travel Office Management Review interview notes for Davison refer to Thomason's statements regarding the First Lady's views on the Travel Office under the heading, "Info SD heard from CC or from [World Wide’s] Fan [Dozier] or Betta [Carney] based on CC's comments," the notes state in pertinent part, "Approx. -

Newsletter for English Teachers About the USA – Virtual Classroom

XX April 2009 Newsletter for English Teachers About the USA – Virtual Classroom In this issue: NATO Summit and G20 Summit | Earth Day | Literature: World Book and Copyright Day & World Intellectual Property Day (WIPO)| In Focus: NATO in Afghanistan | Co.NX on Facebook | Introducing: What’s in a name? NATO Summit and 60th Anniversary In April NATO will be celebrating its sixtieth anniversary. Germany and France are jointly hosting the celebrations. The NATO summit meeting will be held in Baden-Baden and Kehl on the German side of the border and in Strasbourg on the French side. The Summit will focus on the 60th anniversary. The 26 existing member states will be welcoming Albania and Croatia as new members. The meetings will be chaired by the NATO Secretary General, Jaap de Hoop Scheffer. Nicolas Sarkozy, the President (©NATO) of the French Republic, and Angela Merkel, the Chancellor of the Federal Links Republic of Germany, will co-host the meetings. 60 Years of NATO page The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO; French: Organisation du Frequently Asked Questions - NATO Traité de l'Atlantique Nord or "OTAN") is a military alliance, established German Government NATO Summit page by the signing of the North Atlantic Treaty on April 4, 1949. In State.gov: NATO page accordance with that Treaty, the fundamental role of NATO is to United States Mission to NATO safeguard the freedom and security of its member countries by political America.gov: Peacemaking U.S. Embassy Berlin: NATO Summit and military means. Today, NATO plays an increasingly broader role in crisis management and peacekeeping. -

A Climate Chronology Sharon S

Landscape of Change by Jill Pelto A Climate Chronology Sharon S. Tisher, J.D. School of Economics and Honors College University of Maine http://umaine.edu/soe/faculty-and-staff/tisher Copyright © 2021 All Rights Reserved Sharon S. Tisher Foreword to A Climate Chronology Dr. Sean Birkel, Research Assistant Professor & Maine State Climatologist Climate Change Institute School of Earth and Climate Sciences University of Maine March 12, 2021 The Industrial Revolution brought unprecedented innovation, manufacturing efficiency, and human progress, ultimately shaping the energy-intensive technological world that we live in today. But for all its merits, this transformation of human economies also set the stage for looming multi-generational environmental challenges associated with pollution, energy production from fossil fuels, and the development of nuclear weapons – all on a previously unimaginable global scale. More than a century of painstaking scientific research has shown that Earth’s atmosphere and oceans are warming as a result of human activity, primarily through the combustion of fossil fuels (e.g., oil, coal, and natural gas) with the attendant atmospheric emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and other * greenhouse gases. Emissions of co-pollutants, such as nitrogen oxides (NOx), toxic metals, and volatile organic compounds, also degrade air quality and cause adverse human health impacts. Warming from greenhouse-gas emissions is amplified through feedbacks associated with water vapor, snow and sea-ice -

House Section (PDF 751KB)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 165 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, MAY 1, 2019 No. 71 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was verse populations. Providing care to leader, about someone who has changed called to order by the Speaker pro tem- our most at-risk population was a the healthcare system not just for my pore (Mr. CUELLAR). focus of his for 30 years, and it is one district or Columbus, but for the Na- f that he has never lost. Mr. Speaker, I tion, and those two words are ‘‘thank know that firsthand because I had the you.’’ DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO opportunity to witness his work. Thank you for being a leader. Thank TEMPORE I am so honored that David is with us you for being a public servant. But The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- today in the gallery. most of all, Dave P. Blom, thank you, fore the House the following commu- As president of the entire OhioHealth thank you for being my friend. I salute nication from the Speaker: system for the past 17 years, Dave has you. The SPEAKER pro tempore. The WASHINGTON, DC, molded and elevated OhioHealth’s com- May 1, 2019. mitment to all of the communities it Chair would remind Members to avoid I hereby appoint the Honorable HENRY serves as the largest hospital system in referencing occupants of the gallery. CUELLAR to act as Speaker pro tempore on central Ohio. -

Letter of Notification of Presidential Records Release (Clinton)

VIA EMAIL (LM 2014-037) June 22, 2015 The Honorable W. Neil Eggleston Counsel to the President The White House Washington, D.C. 20502 Dear Mr. Eggleston: In accordance with the requirements of the Presidential Records Act (PRA), as amended, 44 U.S.C. §§2201-2209, this letter constitutes a formal notice from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) to the incumbent President of our intent to open Clinton Presidential records in response to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests listed in Attachment A. These records, consisting of 153,589 pages, have been reviewed for all applicable FOIA exemptions, resulting in 28,218 pages restricted in whole and three pages restricted in part. NARA is proposing to open the remaining 125,638 pages in whole and three pages in part. A copy of any records proposed for release under this notice will be provided to you upon your request. We are also concurrently informing former President Clinton’s representative, Bruce Lindsey, of our intent to release these records. Pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 2208(a), NARA will release the records 60 working days from the date of this letter, which is September 16, 2015, unless the former or incumbent President requests a one-time extension of an additional 30 working days or asserts a constitutionally based privilege, in accordance with 44 U.S.C. 2208(b)-(d). Please let us know if you are able to complete your review before the expiration of the 60 working day period. Pursuant to 44 U.S.C. 2208(a)(1)(B), we will make this notice available to the public on the NARA website. -

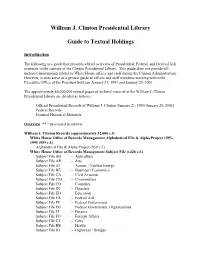

William J. Clinton Presidential Library Guide to Textual Holdings

William J. Clinton Presidential Library Guide to Textual Holdings Introduction The following is a guide that provides a brief overview of Presidential, Federal, and Deed of Gift materials in the custody of the Clinton Presidential Library. This guide does not provide all- inclusive information related to White House offices and staff during the Clinton Administration. However, it does serve as a general guide to offices and staff members working within the Executive Office of the President between January 21, 1993 and January 20, 2001. The approximately 80,000,000 textual pages of archival material at the William J. Clinton Presidential Library are divided as follows. Official Presidential Records of William J. Clinton (January 21, 1993-January 20, 2001) Federal Records Donated Historical Materials Overview ** = processed in entirety William J. Clinton Records (approximately 32,000 c.f) White House Office of Records Management Alphabetical File & Alpha Project 1993- 1995 (959 c.f.) Alphabetical File & Alpha Project (959 c.f.) White House Office of Records Management Subject File (1428 c.f.) Subject File AG – Agriculture Subject File AR – Arts Subject File AT – Atomic / Nuclear Energy Subject File BE – Business / Economics Subject File CA – Civil Aviation Subject File CM – Commodities Subject File CO – Countries Subject File DI – Disasters Subject File ED – Education Subject File FA – Federal Aid Subject File FE – Federal Government Subject File FG – Federal Government, Organizations Subject File FI – Finance Subject File FO – Foreign -

Spring 2009 : Achieving Economic Prosperity And

C LIMATE A LERT A Publication of the Climate Institute | Protecting the balance between climate and life on Earth ACHIEVING ECONOMIC PROSPERITY Volume 19, Volume 2 No. AND LIMATE ROTECTION C P — Spring 2009 FEATURED: Does a Big Economy Need Big Power Plants? Amory Lovins Output-Based Allowances for Efficient Greenhouse Gas Reductions Tom Casten Green Building Doug Gatlin The Smart Grid Bill Nitze ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: A Practical Roadmap for Efficient Vehicles Green Provisions in the U.S. Stimulus Bill Case Studies: The Race to Carbon Neutrality Spring 2009 Climate Institute News from Mexico and DC Volume 19, No. 2 Climate Alert A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT GOOD ECONOMICS: A STRATEGY THAT MIGHT SAVE THE CLIMATE Commentary by John C. Topping, Jr. Climate protection and clean energy nomic sense may be the only hope of transformation are, as Max Jerneck’s enacting legislation to move the US to article indicates, a prominent feature of decisive action and help ensure success the recently enacted economic stimulus of international agreements before we package. As Bill Nitze points out, the pass climate tipping points. Least cost stimulus legislation contains a sizable approaches to greenhouse gas reduc- his issue of the Climate Alert investment toward a Smart Grid that tions may be the only way to assemble highlights the need to integrate T should enhance both the efficiency and the bipartisan coalition needed for climate protection strategy into efforts reliability of the US power system. Doug climate action. The US can realize siz- to catalyze economic recovery in the Gatlin indicates that dramatic increases able emissions reductions at annual US and the globe after the worst buf- in building sector efficiency can, over savings in the tens of billions of dollars feting in generations. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 116 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 165 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, MAY 1, 2019 No. 71 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was verse populations. Providing care to leader, about someone who has changed called to order by the Speaker pro tem- our most at-risk population was a the healthcare system not just for my pore (Mr. CUELLAR). focus of his for 30 years, and it is one district or Columbus, but for the Na- f that he has never lost. Mr. Speaker, I tion, and those two words are ‘‘thank know that firsthand because I had the you.’’ DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO opportunity to witness his work. Thank you for being a leader. Thank TEMPORE I am so honored that David is with us you for being a public servant. But The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- today in the gallery. most of all, Dave P. Blom, thank you, fore the House the following commu- As president of the entire OhioHealth thank you for being my friend. I salute nication from the Speaker: system for the past 17 years, Dave has you. The SPEAKER pro tempore. The WASHINGTON, DC, molded and elevated OhioHealth’s com- May 1, 2019. mitment to all of the communities it Chair would remind Members to avoid I hereby appoint the Honorable HENRY serves as the largest hospital system in referencing occupants of the gallery. CUELLAR to act as Speaker pro tempore on central Ohio. -

Biden White House: Potential Cabinet Nominations and Senior Appointments

Biden White House: Potential Cabinet Nominations and Senior Appointments These are individuals we have either seen reported or are rumored to be in the mix for a cabinet nomination, senior appointment, or other roles in a potential Biden Administration. Please feel free to reach out to us with specific staffing questions. We have long standing ties to Vice President Biden, his campaign staff, members of the transition team, and a great many of the individuals listed in this document. October 21, 2020 Table of Contents • Notes: Slide 3-5 • Potential Cabinet Agency Appointments: Slides 6-70 • Potential Senior White House Appointments: Slides 71-95 • Potential Independent Agency Appointments: Slides 96-112 • Potential Democratic Party Officials: 113-114 • Other Individuals up for Consideration: Slides 115-118 2 Notes • This document compiles all the names we have been hearing for cabinet agencies, independent agencies, senior White House staff, and other potential positions in a Biden Administration. • While our list keeps growing, we have tried to limit the people included under each heading to just those who are likely to be serious contenders for each role, although there are certainly more people who are interested and potentially campaigning for positions. • In some cases, we have specified candidates who might be in the running for the most senior job at an agency, such as a cabinet Secretary position, but acknowledge that some of these individuals might also accept a Deputy Secretary, Undersecretary, or similar role at another agency if someone else is appointed to the top job. Some folks, however, are likely to only be interested in the most senior slot. -

U.S.-China Dialogue on Climate Change BACKGROUND REPORT

Initiative for U.S.-China Dialogue 乔治城大学 美中全球议题对话项目 U.S.-China Dialogue on Climate Change BACKGROUND REPORT Initiative for U.S.-China Dialogue 乔治城大学 美中全球议题对话项目 U.S.-China Dialogue on Climate Change BACKGROUND REPORT About the Initiative on U.S.-China Dialogue on Global Issues The Georgetown Initiative for U.S.-China Dialogue on Global Issues is a university- wide platform for research, teaching, and high-level dialogue among American and Chinese leaders from the public sector, business, and the academy. The initiative is premised on the view that despite inevitable national differences, there remains considerable room for the cultivation of shared U.S. and Chinese approaches to global issues, including climate change, global health, business and trade, peace and security, and economic and social development. Created in January 2016 through a gift from the Hong Kong-based Spring Breeze Foundation, the initiative builds on Georgetown’s core strengths of academic excellence, location in Washington, D.C., and Catholic and Jesuit mission of service to the world. Four core principles organize the initiative’s work—independence, trans- parency, balance, and academic excellence. About this Report This background report on U.S.-China dialogue on climate change was developed under the auspices of the U.S.-China research group on climate change. Background reports in this series provide a general overview of the evolution of a critical issue in U.S.-China relations with wider implications for world affairs. The text of this re- port was crafted by initiative staff under the editorial guidance of the research group, which is led by Dr. -

Withdrawal/Redaction Sheet Clinton Library DOCUMENINO

Withdrawal/Redaction Sheet Clinton Library DOCUMENINO. SUB.IECTAriTLE DATE RESTRICTION AND T>'PE 001. email [email protected] to Todd Stern at 20:35:32.00. 01 /13/1999 b(7)(C), b(7)(F), b(6) Subject: WAVES Confirmation. DOB and SSN. [partial] (1 page) 002. email WAVES [email protected] to Todd Stern at 20:15:06.00. 01 /13/1999 b(7)(C), b(7)(F), b(6) Subject: WAVES Confirmation. DOB and SSN. [partial] (1 page) 003. email Lotus Pager Gateway to Todd Stem at 13:58:58.00. Subject: 01/14/1999 Personal Misfile [personal] (1 page) COLLECTION: Clinton Presidential Records Automated Records Management System [Email WHO ([To: Todd Stern]) OA/Box Number: 500000 FOLDER TITLE: [01/13/1999-01/14/1999] 2013-0914-F abl439 RESTRICTION CODES Presidential Records Act - j44 U.S.C. 2204(a)l Freedom of Information Act - |5 U.S.C. 552(b)j PI National Security Classifled Information 1(a)(1) of the PRA] b(I) National security classifled information j(b)(I) of the FOIAj P2 Relating to the appointment to Federal offlce j(a)(2) of the PRAj b(2) Release would disclose internal personnel rules and practices of P3 Release would violate a Federal statute j(a)(3) of the PR.\| an agency j(b)(2) of the FOIAj P4 Release would disclose trade secrets or confldential commercial or b(3) Release would violate a Federal statute j(b)(3) of the FOLAj flnancial information 1(a)(4) of the PRAj b(4) Release would disclose trade secrets or confldential or flnancial PS Release would disclose confldential advice between the President information 1(b)(4) of the FOIAj and his advisors, or between such advisors ja)(5) of the PRAj b(6) Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of P6 Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of personal privacy 1(b)(6) of the FOIAj personal privacy j(a)(6) of the PRAj b(7) Release would disclose information compiled for law enforcement purposes j(b)(7)of the FOIAj C.