Durham Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impact Case Study (Ref3b) Institution: University of Central Lancashire

Impact case study (REF3b) Institution: University of Central Lancashire Unit of Assessment: 26 - Sport and Exercise Sciences, Leisure and Tourism Title of case study: Sport, „Visual Culture‟ and Museums 1. Summary of the impact (indicative maximum 100 words) Research undertaken by Hughson has impacted on the decision-making of two museums, principally the National Football Museum (NFM) in England and the National Sports Museum (NSM) in Australia. In the NFM, research has informed the acquisition and display of items for the permanent collection and temporary exhibition, led to an appointment as historical advisor to the selection committee of the National Football Hall of Fame, and has also supported the NFM‟s successful bid for „Designation‟ status with the Arts Council. With regard to the NSM the research has informed the public education dimension of a major exhibition on Olympic posters. 2. Underpinning research (indicative maximum 500 words) Hughson‟s published research on the cultural history of sport, the relationship between sport, art and design, and on the relationship between sport and cultural policy and the implications for museums underpins the impact being claimed within this case study. Five published peer reviewed works contain this research; the bibliographical details are set out in section 3 of this document. The first three of the listed items are included within Hughson‟s four published items returned with REF 2014. Hughson‟s research expertise on sport within art was established in the monograph The Making of Sporting Cultures. In various chapters of the book, the representation of sportive movement and symbolism from the ancient to the modern – Myron‟s Discobolus to Dali‟s Cosmic Athlete – is discussed. -

100% 100% 100% 100% Study at Recommend Learner Progession to SUFC Our Courses Achievement University

100% 100% 100% 100% Study at Recommend Learner Progession to SUFC our courses achievement University Welcome to The Sheffield United Community Foundation Sports Education Academy Sheffield United Community Foundation are a bespoke, high quality Education and Training provider specialising in the delivery of accredited sports based qualifications in further and higher education. Our aim is to prepare our students for a successful career in the football and wider sports industries The units are enjoyable to learn, practical lessons make the learning fun, enrichment allows us to socialise with classmates and represent the club in a professional manner. There are plenty of progression opportunities after graduating and a variety of employment opportunities too” LEARN TRAIN PLAY WORK “YOUR CLUB, YOUR COURSE, YOUR CAREER” What you do and what you achieve at Sheffield United Community Foundation will hopefully have a positive impact on the rest of your life, so please make the most of the opportunities available. We will help you do that by providing you with passionate and excellent teaching, facilities and support. We’ll give you hands on experience that will make your CV stand out from the pile, the confidence to shine in an interview and the ability to handle yourself when you start at work. It’s hard work, but you’ll enjoy it. And we’ll put in everything we’ve got to make sure you succeed. #Unitedasone Courses Level 2 Diploma in Sport The Level 2 Diploma in Sport is a specialist work related course built around the NCFE platform. The course is to build knowledge of practical sports performance, training and personal fitness, running sports events and sport community volunteering. -

National Football Museum

NATIONAL FOOTBALL MUSEUM Athanasios Kotoulas HISTORY The National Football Museum is a museum in Manchester, which is located in the Urbis building. The purpose of the museum is to preserve, conserve and interpret the most important collections of the English National Football history. The museum opened on the 16th February, 2001. The original location was outside of Preston, Deepdale and Lancashire. In 2012, it was moved to Manchester. The president of the museum is the Manchester United Legend, Sir Bobby Chartlon. Source: www.wikipedia.com BUILDING LAYOUT Level One Level Two Level Three Level Four Level Five and Six LEVEL ONE <Back It’s the largest floor of the whole building Features: Ιtems such as the first ever rule book from 1863 and the shirt from the first ever international football match between England and Scotland. Including the original painting of L.S. Lowry's "Going to the Match“. Information about the various competitions and leagues, with the original version of the FA Cup and various replica trophies. A section dedicated to world football, with the ball from the first ever World Cup Final, the matchball from the 1966 World Cup Final, Maradona's "Hand of God" shirt and the UEFA Cup Winners Cup trophy. Information about various stadiums and designs, with an original turnstile from the old Wembley Stadium and some original wooden seats. various footage and clippings from old matches, including a sheepskin coat worn by John Motson. Interactive screens with information on most league clubs in England. A brief look at the scope of footballers, including the only Victoria Cross won by a professional footballer and the painting "The Art of the Game" portraying Eric Cantona. -

Women's Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011

Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 A Project Funded by the UEFA Research Grant Programme Jean Williams Senior Research Fellow International Centre for Sports History and Culture De Montfort University Contents: Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971- 2011 Contents Page i Abbreviations and Acronyms iii Introduction: Women’s Football and Europe 1 1.1 Post-war Europes 1 1.2 UEFA & European competitions 11 1.3 Conclusion 25 References 27 Chapter Two: Sources and Methods 36 2.1 Perceptions of a Global Game 36 2.2 Methods and Sources 43 References 47 Chapter Three: Micro, Meso, Macro Professionalism 50 3.1 Introduction 50 3.2 Micro Professionalism: Pioneering individuals 53 3.3 Meso Professionalism: Growing Internationalism 64 3.4 Macro Professionalism: Women's Champions League 70 3.5 Conclusion: From Germany 2011 to Canada 2015 81 References 86 i Conclusion 90 4.1 Conclusion 90 References 105 Recommendations 109 Appendix 1 Key Dates of European Union 112 Appendix 2 Key Dates for European football 116 Appendix 3 Summary A-Y by national association 122 Bibliography 158 ii Women’s Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011 Abbreviations and Acronyms AFC Asian Football Confederation AIAW Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women ALFA Asian Ladies Football Association CAF Confédération Africaine de Football CFA People’s Republic of China Football Association China ’91 FIFA Women’s World Championship 1991 CONCACAF Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Association Football CONMEBOL -

Louise Hatch 462A Kingsland Rd, Dalston, London E8 4AE Email: [email protected] Mobile: +44(0)7507645775 PROFILE with O

Louise Hatch 462a Kingsland Rd, Dalston, London E8 4AE Email: [email protected] Mobile: +44(0)7507645775 PROFILE With over 14 year’s experience delivering a wide variety of major events in the UK and worldwide, I am a passionate, committed professional, who rises to any challenge and is willing to go that extra mile to deliver. I have Major Events experience covering: Venue Operations, Event Management, Project Planning knowledge covering various sectors to include Sport, Commercial Experiences and Broadcast. EVENT DELIVERY o Mitel Major League Baseball London Series, Boston Red Socks v New York Yankees. London Stadium o ITV Palooza, Royal Festival Hall, London o ITV company wide Christmas parties o ITV Sport & Screwfix World Cup sponsorship event, Yeovil, UK o London 2017 World Athletics, London Stadium o MIPTV, Cannes France. o I Am Team GB, Nations Biggest Sports Day: Coronation Street set, Ricoh Arena, Bath City Centre, Hope Cove beach, Ullswater Yacht Club, Reading Rowing Club o FA Cup Final, FA Cup Semi Finals, Community Shield and FA Women’s Cup Final - Wembley Stadium o England Internationals - Men and Women’s - Wembley Stadium, o England U21 and Women’s Internationals - across the UK o The Invictus Games, Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park; Multi-Sport Venue for Archery, Indoor Rowing & Powerlifting o Football League Awards – The Brewery, London o Various Commercial conferences - various Football League Clubs across England. o 125th Anniversary FL Museum Exhibition Launch - National Football Museum, Manchester o Capital One -

Stanya Kahn, ‘It’S Cool, About Her Personal Struggles, Stress, and Working Life in a Home for Mental Patients

Mental health at the movies: 1 THE SHRIEKING Violet Jesus’ Son (directed by Alison 2 is three! I can’t believe it’s three years Maclean) by Richard Howe since the Shrieking Violet fan- “I FELT about the hallway of the Bev- zine started, back in summer 2009. erly Home mental centre as about the The first issue, conceived as an alternative guide to place where, between our lives on this Manchester, was published at the start of August in earth, we go back to mingle with other 2009, containing articles on canal boats, street names, souls waiting to be born.” the demise of B of the Bang and the regeneration of north Manchester among other topics – along with, Jesus’ Son is based on acclaimed all importantly, a recipe for blackberry crumble! biographical novel by Beat author Over the course of the nineteen issues of the Shriek- Denis Johnson, who guest stars as a ing Violet I’ve produced to date, certain preoccupa- peeping tom with a knife in his eye tions have emerged, and subjects such as public socket. Set on the North West coast art, public transport, history, food and tea have all of America in the ‘70s and named remained constants; fittingly, this issue contains an after a Lou Reed lyric, it’s gonna be appreciation of post-war murals by Joe Austin, a a wild ride. Jesus’ Son gets my vote tribute to tea by Anouska Smith, a lament on the as best ever female-directed film; not fragmentation of our railway system by Kenn Taylor, that gender matters, that’s just to get your mind bubbling and percolating a profile of Manchester-associated radical and ec- We follow narrator, the journey of lovable antihero nicknamed ‘Fuck Head’ (Billy Crudup) centric Pierre Baume and a recipe for bread from the from drug addiction to compassion. -

Insite-2020.Pdf

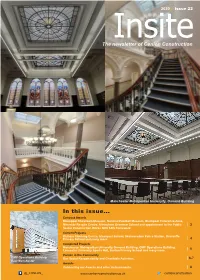

2020 | Issue 22 The newsletterInsite of Conlon Construction Manchester Metropolitan University, Ormond Building In this issue... Contract Awards Blackpool Showtown Museum, National Football Museum, Blackpool Enterprise Zone, Mereside Respite Centre, Altrincham Grammar School and appointment to the Public | 3 Sector Construction Works NHS SBS framework. Current Projects Oldham Climbing Centre, Stockport School, Skelmersdale Police Station, Briercliffe Primary School and many more. | 4 Completed Projects Manchester Metropolitan University Ormond Building, GMP Operations Building, Lancaster University Sports Hall, Gorton Primary School and many more. | 5 Conlon in the Community GMP Operations Building Our Social Responsibility and Charitable Activities. | 6-7 East Manchester Awards Celebrating our Awards and other Achievements. | 8 @_CONLON_ www.conlon-construction.co.uk conlonconstruction Welcome to the latest edition of Insite, the newsletter of Conlon Construction. As you read on you will see that we have had another Welcome very exciting year, filled with celebrations, project Chairman’s Update by Michael Conlon completions, contract awards and community activities. I always try to open this annual round up with These changes have been hard to adapt to but we something cheering and upbeat but 2020 has made wish to thank all of our colleagues for their willingness this more challenging than usual. Without a doubt, to embrace them. Even though our industry wasn’t memories of 2020 will be dominated by the impact of applauded on Thursday evenings, I hope you will agree the Covid-19 virus upon all of our lives. all of our fellow workers should also be recognised. At an early point in the Government’s decisions on If I could now turn to matters more close to home there how to combat the virus, construction was designated are still, even in such a difficult year, numerous events an essential industry. -

The Football Association Challenge the Cup Final

The Football Association Challenge The Cup Final Cup Final Facts • The match is widely known as just the Cup Final. • It is the last match in the Football Association (FA) Challenge Cup. • It has about 86 000 spectators and millions of TV viewers. • The trophy (winner’s cup) is only on loan to the winning side. • It is the oldest cup competition in the world, first played in the 1871 - 72 season. Who Can Enter? The Challenge Cup competition is open to any club in the top ten levels of the English Football League. Once clubs have registered to play, the tournament is organised into 12 randomly drawn rounds, followed by the semi-finals and finals. The higher ranked teams join the competition in later rounds when some of the lower ranked teams have been knocked out. What Do the Winners Receive? The winners of the final match receive the Football Association Cup, the FA Cup. It comes in three parts; the base, the cup and a lid. Over the years, there have been two designs of trophy and five cups have been made. The first cup, known as the ‘little tin idol’, was stolen in 1895 and never returned. An exact replica was made and used until 1910. From 1911, a new design was made. In 1992, another copy was made as the cup was wearing out from being handled, and another replacement was made in 2014. The cup is presented at the end of the match, giving the engraver just five minutes to engrave the winning team on the silver band on the base. -

Report on National Football Museum at Urbis to Executive on 21 October

Manchester City Council Item 6 Executive 21 October 2009 Manchester City Council Report for Resolution Report To: Executive – 21 October 2009 Subject: National Football Museum at Urbis Report of: Chief Executive Summary This report informs Members of a recent approach by the National Football Museum to relocate to Urbis and outlines the initial feasibility work undertaken to assess viability. Approval is sought to the use of the current revenue grant to Urbis of £2m to accommodate the Football Museum alongside current activity in Urbis and to a capital contribution to convert the building, subject to additional funding from the Northwest Development Agency. Recommendations • To note, and welcome, the recent approach by the National Football Museum to relocate to Manchester, at Urbis. • To note that the Millennium Quarter Trust (MQT), who operate Urbis on behalf of the Council, have approved the move in principle on the basis that the current innovative work at Urbis as a centre for popular culture will be further enhanced by this partnership. • To note the work completed to date to assess the scope of work and costs associated with conversion works to Urbis and to develop a business case. • To approve, in principle, the use of the current revenue support grant to Urbis to fund the National Football Museum at Urbis. • To approve, in principle, a capital contribution from the Capital Fund subject to securing significant partnership funding. • To request a further report before Christmas confirming detailed funding and delivery arrangements once a response to Manchester’s offer has been received from the National Football Museum and approved by the Millennium Quarter Trust. -

The Best History Lesson Ever!

The best history lesson ever! Early Years & Primary Learning 2017 - 2018 L @NFM_learn WE TEACH HISTORY... We teach much more Pickles and the Animating History Going to the Match than just a game... Stolen World Cup Y6 / 90 mins / max. 15 children Y3 – 6 / 1 hour / max. 35 children Y1 – 2 / 1 hour / max. 35 children Our fun and inspiring learning programme uses Participate in our new creative session using Explore the sights, smells and sounds of match unique objects and amazing stories to enthuse Meet Pickles the dog and discover how he innovative technology to animate local history days in the past. Pupils dress up in supporters’ sniffed out the stolen world cup trophy in 1966. using real museum objects. Pupils use clothes, investigate museum objects and use and engage your pupils. Use the hook of football This interactive session uses puppets, role time-lapse and stop-motion animation role play to describe their experiences. to bring learning to life! play and exploration of our 1966 World to create imaginative stories. Cup collection. Trench Football Football and Local History Football and WW1 Y3 – 6 / 1 hour / max. 35 children Y2 - 5 / 1 hour / max. 35 children Y5 – 6 / 1 hour / max. 35 children Discover more about football's role during Discover more about Manchester’s rich Find out about the controversial decision the Great War and be inspired by our war footballing history. Learn about the highs and to suspend football, see who joined the time, morale-boosting football puzzles lows of United and City and the developments WE TEACH EARLY YEARS.. -

View Our Sample Article PDF Here

Soccer History Issue 18 THE FRENCH MENACE; THE MIGRATION OF BRITISH PLAYERS TO FRANCE IN THE 1930S In the spring of 1932 the pages of the national and sporting press in England informed readers that domestic football was under threat from the ‘French Menace’. This comprised a well-publicised, but rather futile, attempt to attract two of Chelsea’s star players, Tommy Law and Hugh Gallacher, to play in the newly formed French professional league, effectively tearing up their English contracts in return for a reportedly large sum of money. The French Menace followed the ‘American Menace’ and the ‘Irish Menace’, occasions when British players had been induced to break their contracts and migrate to play in the American Soccer and Irish Free State Leagues. The potential migration of players was a menace because in each case, initially at least, there was a threat to the fundamental structures that enabled clubs to control their players: the retain-and-transfer system and (in England) the maximum wage. The British associations were passing through an isolationist phase and had left FIFA, hence agreements on player transfers only held on transactions between the Home Countries. A player moving to a club in another association could do so, in theory, without hindrance and without the payment of a transfer fee. In practice, as each ‘menace’ arose the FA was forced to reach agreements with local bodies to ensure that players could be held to their contract. Football in France was nominally amateur prior to 1932, but this concealed the advent of a form of professionalism that had gathered pace in the years after the First World War. -

Eyewitness. Soccer

EYEWITNESS BOOKS Eyewitness SOCCER 1930s French hair- 1905 match oil advertisement holder 1900s soccer ball pumps Jay Jay Okocha of 1910s 1930s Nigeria 1900s shin pads shin pads shin pads Early 20th- century soccer ball stencils 1966 World Cup soccer ball 1930s painting of a goalkeeper 1998 World Cup soccer ball Early 20th- Early 20th- century century porcelain porcelain figure Eyewitness figure SOCCER Written by HUGH HORNBY Photographed by ANDY CRAWFORD 1912 soccer ball in association with THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL MUSEUM, UK LONDON, NEW YORK, 1900s plaster MELBOURNE, MUNICH, AND DELHI figure Project editor Louise Pritchard Art editor Jill Plank Assistant editor Annabel Blackledge Assistant art editor Yolanda Belton Managing art editor Sue Grabham 19th- Senior managing art editor Julia Harris century Production Kate Oliver jersey Picture research Amanda Russell DTP Designer Andrew O’Brien and Georgia Bryer THIS EDITION Consultants Mark Bushell, David Goldblatt Editors Kitty Blount, Sarah Philips, Sue Nicholson, Victoria Heywood-Dunne, Marianne Petrou Art editors Andrew Nash, David Ball Managing editors Andrew Macintyre, Camilla Hallinan Managing art editors Jane Thomas, Martin Wilson Publishing manager Sunita Gahir 1925 Australian Production editors Siu Yin Ho, Andy Hilliard International shirt Production controllers Jenny Jacoby, Pip Tinsley DK picture library Rose Horridge, Myriam Megharbi, Emma Shepherd Picture research Carolyn Clerkin, Will Jones U.S. editorial Beth Hester, John Searcy U.S. publishing director Beth Sutinis 1905 book U.S.