Exploring the Use of Little Cigars by Students at a Historically Black University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Local Business Database Local Business Database: Alphabetical Listing

Local Business Database Local Business Database: Alphabetical Listing Business Name City State Category 111 Chop House Worcester MA Restaurants 122 Diner Holden MA Restaurants 1369 Coffee House Cambridge MA Coffee 180FitGym Springfield MA Sports and Recreation 202 Liquors Holyoke MA Beer, Wine and Spirits 21st Amendment Boston MA Restaurants 25 Central Northampton MA Retail 2nd Street Baking Co Turners Falls MA Food and Beverage 3A Cafe Plymouth MA Restaurants 4 Bros Bistro West Yarmouth MA Restaurants 4 Family Charlemont MA Travel & Transportation 5 and 10 Antique Gallery Deerfield MA Retail 5 Star Supermarket Springfield MA Supermarkets and Groceries 7 B's Bar and Grill Westfield MA Restaurants 7 Nana Japanese Steakhouse Worcester MA Restaurants 76 Discount Liquors Westfield MA Beer, Wine and Spirits 7a Foods West Tisbury MA Restaurants 7B's Bar and Grill Westfield MA Restaurants 7th Wave Restaurant Rockport MA Restaurants 9 Tastes Cambridge MA Restaurants 90 Main Eatery Charlemont MA Restaurants 90 Meat Outlet Springfield MA Food and Beverage 906 Homwin Chinese Restaurant Springfield MA Restaurants 99 Nail Salon Milford MA Beauty and Spa A Child's Garden Northampton MA Retail A Cut Above Florist Chicopee MA Florists A Heart for Art Shelburne Falls MA Retail A J Tomaiolo Italian Restaurant Northborough MA Restaurants A J's Apollos Market Mattapan MA Convenience Stores A New Face Skin Care & Body Work Montague MA Beauty and Spa A Notch Above Northampton MA Services and Supplies A Street Liquors Hull MA Beer, Wine and Spirits A Taste of Vietnam Leominster MA Pizza A Turning Point Turners Falls MA Beauty and Spa A Valley Antiques Northampton MA Retail A. -

TRACEY A. MASH and ANJANETTA LINGARD Plaintiffs V. BROWN

TRACEY A. MASH and ANJANETTA LINGARD Plaintiffs v. BROWN & WILLIAMSON TOBACCO CORPORATION Defendant UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MISSIOURI (ST. LOUIS) Case No. 4:03CV00485TCM September 20, 2004 PURPOSE This backgrounder has been prepared by some the defendant in this case to provide a concise reference document on the case of Tracey A. Mash and Anjanetta Lingard v. Brown & Williamson Corporation, No. 4:03CV00485TCM. It is not a court document. THE PLAINTIFFS: This lawsuit was filed by Tracey A. Mash and Anjanetta Lingard on March 6, 2003 in state court in Missouri. It was later removed to federal court. The plaintiffs are the daughters of Stella Hale who died on Aug. 16, 2001. Plaintiffs allege Ms. Hale died from lung cancer caused by KOOL cigarettes. THE DEFENDANTS: The sole defendant is Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation (B&W), formerly headquartered in Louisville, Ky. Its major brands included Pall Mall, KOOL, GPC, Carlton, Lucky Strike and Misty. As of July 31, 2004, Brown & Williamson’s domestic tobacco business merged with R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, a New Jersey corporation, to form R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, a North Carolina corporation (“RJRT”). RJRT, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Reynolds American, Inc., is headquartered in Winston-Salem, N.C. It is the nation’s second largest manufacturer of cigarettes. Its brands include those of the former B&W as well as Winston, Salem, Camel and Doral. B&W is represented by Andrew R. McGaan of Kirkland & Ellis, LLP, in Chicago; Fred Erny of Dinsmore & Shohl in Cincinnati, Ohio; and Frank Gundlach of Armstrong Teasdale in St. -

Current Status of the Reduced Propensity Ignition Cigarette Program in Hawaii

Hawaii State Fire Council Current Status of the Reduced Propensity Ignition Cigarette Program in Hawaii Submitted to The Twenty-Eighth State Legislature Regular Session June 2015 2014 Reduced Ignition Propensity Cigarette Report to the Hawaii State Legislature Table of Contents Executive Summary .…………………………………………………………………….... 4 Purpose ..………………………………………………………………………....................4 Mission of the State Fire Council………………………………………………………......4 Smoking-Material Fire Facts……………………………………………………….............5 Reduced Ignition Propensity Cigarettes (RIPC) Defined……………………………......6 RIPC Regulatory History…………………………………………………………………….7 RIPC Review for Hawaii…………………………………………………………………….9 RIPC Accomplishments in Hawaii (January 1 to June 30, 2014)……………………..10 RIPC Future Considerations……………………………………………………………....14 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….............15 Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………17 Appendices Appendix A: All Cigarette Fires (State of Hawaii) with Property and Contents Loss Related to Cigarettes 2003 to 2013………………………………………………………18 Appendix B: Building Fires Caused by Cigarettes (State of Hawaii) with Property and Contents Loss 2003 to 2013………………………………………………………………19 Appendix C: Cigarette Related Building Fires 2003 to 2013…………………………..20 Appendix D: Injuries/Fatalities Due To Cigarette Fire 2003 to 2013 ………………....21 Appendix E: HRS 132C……………………………………………………………...........22 Appendix F: Estimated RIPC Budget 2014-2016………………………………...........32 Appendix G: List of RIPC Brands Being Sold in Hawaii………………………………..33 2 2014 -

Appendix 1. Categorization of Cigarette Brands As Either Premium Or Discount

Appendix 1. Categorization of Cigarette Brands as either Premium or Discount Category Name of Cigarette Brand Premium Accord, American Spirit, Barclay, Belair, Benson & Hedges, Camel, Capri, Carlton, Chesterfield, Davidoff, Du Maurier, Dunhill, Dunhill International, Eve, Kent, Kool, L&M, Lark, Lucky Strike, Marlboro, Max, Merit, Mild Seven, More, Nat Sherman, Newport, Now, Parliament, Players, Quest, Rothman’s, Salem, Sampoerna, Saratoga, Tareyton, True, Vantage, Virginia Slims, Winston, Raleigh, Business Club Full Flavor, Ronhill, Dreams Discount 24/7, 305, 1839, A1, Ace, Allstar, Allway Save, Alpine, American, American Diamond, American Hero, American Liberty, Arrow, Austin, Axis, Baileys, Bargain Buy, Baron, Basic, Beacon, Berkeley, Best Value, Black Hawk, Bonus Value, Boston, Bracar, Brand X, Brave, Brentwood, Bridgeport, Bronco, Bronson, Bucks, Buffalo, BV, Calon, Cambridge, Campton, Cannon, Cardinal, Carnival, Cavalier, Champion, Charter, Checkers, Cherokee, Cheyenne, Cimarron, Circle Z, Class A, Classic, Cobra, Complete, Corona, Courier, CT, Decade, Desert Gold, Desert Sun, Discount, Doral, Double Diamond, DTC, Durant, Eagle, Echo, Edgefield, Epic, Esquire, Euro, Exact, Exeter, First Choice, First Class, Focus, Fortuna, Galaxy Pro, Gauloises, Generals, Generic/Private Label, Geronimo, Gold Coast, Gold Crest, Golden Bay, Golden, Golden Beach, Golden Palace, GP, GPC, Grand, Grand Prix, G Smoke, GT Ones, Hava Club, HB, Heron, Highway, Hi-Val, Jacks, Jade, Kentucky Best, King Mountain, Kingsley, Kingston, Kingsport, Knife, Knights, -

Studies in African Linguistics Volume 44, Number 2, 2015 Mauro Tosco

Studies in African Linguistics Volume 44, Number 2, 2015 FROM ELMOLO TO GURA PAU: A REMEMBERED CUSHITIC LANGUAGE OF LAKE TURKANA AND ITS POSSIBLE REVITALIZATION Mauro Tosco University of Turin This article discusses the “extinct” Elmolo language of the Lake Turkana area in Kenya. A surprisingly large amount of the vocabulary of this Cushitic language (whose community shifted to Nilotic Samburu in the 20th century), far from being lost and forgotten, is still known and is, to a certain extent, still used. The Cushitic material contains both specialized vocabulary (for the most part related to fishing) and miscellaneous and general words, mostly basic lexicon. It is this part of the lexicon that is the basis of recent revitalization efforts currently undertaken by the community in response to the changing political situation in the area. The article describes the Cushitic material still found among the Elmolo and discusses the current revitalization efforts (in which the author has, albeit marginally, taken part), pinpointing its difficulties and uncertain results. The article is followed by a glossary listing all the Cushitic words still in use or remembered by at least a part of the community.1 Keywords: Elmolo, Cushitic, language revitalization, language classification 1. The Elmolo people today The Elmolo are a small fishing community living near Lake Turkana, in northeast Kenya. Long considered “the smallest tribe of Kenya” and on the verge of extinction, the Elmolo have actually been increasing in number in recent years; while less than 100 people were counted by Spencer (1973), and Heine (1980) gave their number as approximately 200, they are today approximately 700 (Otiero 2008: 5 gives their number as 613 following a headcount he personally conducted). -

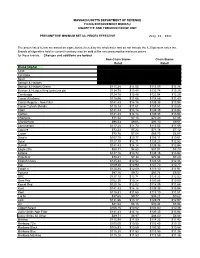

Cigarette Minimum Retail Price List

MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE FILING ENFORCEMENT BUREAU CIGARETTE AND TOBACCO EXCISE UNIT PRESUMPTIVE MINIMUM RETAIL PRICES EFFECTIVE July 26, 2021 The prices listed below are based on cigarettes delivered by the wholesaler and do not include the 6.25 percent sales tax. Brands of cigarettes held in current inventory may be sold at the new presumptive minimum prices for those brands. Changes and additions are bolded. Non-Chain Stores Chain Stores Retail Retail Brand (Alpha) Carton Pack Carton Pack 1839 $86.64 $8.66 $85.38 $8.54 1st Class $71.49 $7.15 $70.44 $7.04 Basic $122.21 $12.22 $120.41 $12.04 Benson & Hedges $136.55 $13.66 $134.54 $13.45 Benson & Hedges Green $115.28 $11.53 $113.59 $11.36 Benson & Hedges King (princess pk) $134.75 $13.48 $132.78 $13.28 Cambridge $124.78 $12.48 $122.94 $12.29 Camel All others $116.56 $11.66 $114.85 $11.49 Camel Regular - Non Filter $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Camel Turkish Blends $110.14 $11.01 $108.51 $10.85 Capri $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Carlton $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Checkers $71.54 $7.15 $70.49 $7.05 Chesterfield $96.53 $9.65 $95.10 $9.51 Commander $117.28 $11.73 $115.55 $11.56 Couture $72.23 $7.22 $71.16 $7.12 Crown $70.76 $7.08 $69.73 $6.97 Dave's $107.70 $10.77 $106.11 $10.61 Doral $127.10 $12.71 $125.23 $12.52 Dunhill $141.43 $14.14 $139.35 $13.94 Eagle 20's $88.31 $8.83 $87.01 $8.70 Eclipse $137.16 $13.72 $135.15 $13.52 Edgefield $73.41 $7.34 $72.34 $7.23 English Ovals $125.44 $12.54 $123.59 $12.36 Eve $109.30 $10.93 $107.70 $10.77 Export A $120.88 $12.09 $119.10 $11.91 -

ISAAC KOOL (COOL Or COLE)

r-E" cA* csii a.k^ i^a t 3^ ISAAC KOOL (COOL or COLE) CATHARINE SERVEN, MARRIED OCT. 15, 1764, AT (then Tappan^ Rockland pan of orange) Co.^ N . Y. THEIR DESCENDANTS COMPLETE TO MAY I, 1876. ALSO THEIR AMERICAN ANCESTORS FROM THE SETTLEMENT OK NEW YORK CITY. COMPILED FOR THE FAMILY REV. DAVID COLE, D.D., (Pastor the of Reformed Church of Yonkers, N. Y. ,) ONE OF THEIR GREAT-GRANDCHILDREN. -*• f NEW YORK: L JOHN F. TROW & SON, PRINTERS. 1876. *^^^(^^(C^%^^^ X^^t^/^^^n^^ >^ c?c^^^^ ISAAC KOOL (COOL or COLE) AND CATHARINE SERVEN, MARRIED OCT. 15, 1764, AT Tappan^ Rockland (then part of orange) Co., N'. 1. THEIR DESCENDANTS COMPLETE TO MAY I, 1876. ALSO THEIR AMERICAN ANCESTORS FKOM THE SETTLEMENT OK NEW YORK CITY. COMPILED FOR THE FAMILY BY REV. DAVID COLE, D.D., (Pastor of the Reformed Church of Yonkers, N. }'.J ONE OF THEIK GKEAT-GRANDCHILDREN. NEW YORK: JOHN F. TROW & SON, PRINTERS. 1876. Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1S76, By Rev. DAVID COLE, In ;he Office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington. ^i/(: ; 1^ GENERAL INDEX OF CONTENTS. Introductory Statement to the Family. Remarks on Holland Names. York City) from Chronicles of Holland from 1579 to 1621 ; of New Amsterdam (now New 1609 to 1674; and of the Reformed (Dutch) Church in America from 1619 to 1700. Isaac Cole and Catharine Serven. PART I. —Their American Ancestors from the settlement of New Amsterdam, compris- ing one Holland-born and three American-born generations. This part also contains a beginning of the genealogy of the Holland Meyer family in America (continued in Part III). -

Reynolds American Completes Acquisition of Lorillard and Related Divestitures

Reynolds American Inc. P.O. Box 2990 Winston-Salem, NC 27102-2990 Contact: Media: David Howard Investor Relations: Morris Moore RAI 2015-15 (336) 741-3489 (336) 741-3116 Reynolds American completes acquisition of Lorillard and related divestitures WINSTON-SALEM, N.C. – June 12, 2015 – Reynolds American Inc. (NYSE: RAI) has completed its acquisition of Lorillard, Inc. and related divestiture transactions. As a result of the acquisition, Lorillard is a wholly owned subsidiary of RAI, and former Lorillard shareholders will own approximately 15 percent of RAI’s common stock. RAI’s operating companies have key brands across major industry categories: Newport, Camel, Pall Mall and Natural American Spirit in combustible cigarettes; Grizzly in smokeless tobacco; and VUSE in the vapor market. In the acquisition, former Lorillard shareholders will receive $50.50 in cash and 0.2909 of a share of RAI common stock for each share of Lorillard common stock they owned. In the related divestiture transactions, subsidiaries of RAI have sold the KOOL, Salem, Winston, Maverick and blu eCigs brands, and other assets and liabilities, to ITG Brands, LLC, a subsidiary of Imperial Tobacco Group, PLC, for total consideration of approximately $7.1 billion in cash. Additionally, British American Tobacco p.l.c. maintained its approximately 42 percent ownership in RAI through an equity investment of approximately $4.7 billion. “As a result of this acquisition, Reynolds American has a significantly strengthened, balanced and diversified portfolio of iconic brands across all key categories – the most balanced in the industry,” said Susan M. Cameron, RAI’s president and chief executive officer. -

Deletions from Certified Alabama Brands

Deletions From Certified Alabama Brands Brand Family Date Deleted Last Sales Date Manufacturer DURANT 12-May-04 11-Jun-04 ALLIANCE TOBACCO CORP BUENO 15-Jun-09 15-Jul-09 ALTERNATIVE BRANDS TRACKER 17-May-07 16-Jun-07 ALTERNATIVE BRANDS TRACKER 30-Sep-13 30-Oct-13 ALTERNATIVE BRANDS TUCSON 14-Aug-07 13-Sep-07 ALTERNATIVE BRANDS TUCSON 30-Sep-13 30-Oct-13 ALTERNATIVE BRANDS TUCSON (RYO) 17-May-07 16-Jun-07 ALTERNATIVE BRANDS VICTORY BRAND 12-May-04 11-Jun-04 ALTERNATIVE BRANDS UNION 19-Jun-13 19-Jul-13 AMERICAN CIGARETTE COMPANY, INC. US ONE 19-Jun-13 19-Jul-13 AMERICAN CIGARETTE COMPANY, INC. SAVANNAH 26-May-05 25-Jun-05 ANDERSON TOBACCO COMPANY LLC SOUTHERN CLASSIC 12-May-04 11-Jun-04 ARGENSHIP PARAGUAY S A THE BRAVE 10-Jun-06 10-Jul-06 BEKENTON USA RALEIGH EXTRA 17-Mar-04 16-Apr-04 BROWN & WILLIAMSON TOBACCO CORPORATION CORONAS 10-May-06 09-Jun-06 CANARY ISLANDS CIGARS COMPANY PALACE 10-May-06 09-Jun-06 CANARY ISLANDS CIGARS COMPANY RECORD 10-May-06 09-Jun-06 CANARY ISLANDS CIGARS COMPANY VL 10-May-06 09-Jun-06 CANARY ISLANDS CIGARS COMPANY KINGSBORO 18-Jul-10 17-Aug-10 CAROLINA TOBACCO COMPANY ROGER 18-Jul-10 17-Aug-10 CAROLINA TOBACCO COMPANY DAVENPORT 26-May-05 25-Jun-05 CARRIBBEAN-AMERICAN TOBACCO CORP FREEMONT 21-May-08 20-Jun-08 CARRIBBEAN-AMERICAN TOBACCO CORP KINGSLEY 26-May-05 25-Jun-05 CENTURION INDUSTRIA E COMERCIO DE CIGARROS 901'Z 07-Jun-11 07-Jul-11 CHEYENNE INTERNATIONAL LLC CAYMAN 07-Jun-11 07-Jul-11 CHEYENNE INTERNATIONAL LLC PULSE 07-Jun-11 07-Jul-11 CHEYENNE INTERNATIONAL LLC CT 07-May-04 06-Jun-04 CIGTEC TOBACCO LLC -

Printmgr File

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 6-K REPORT OF FOREIGN PRIVATE ISSUER Pursuant to Rule 13a-16 or 15d-16 under the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 October 2, 2018 Commission File Number: 001-38159 BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO P.L.C. (Translation of registrant’s name into English) Globe House 4 Temple Place London WC2R 2PG United Kingdom (Address of principal executive office) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant files or will file annual reports under cover of Form 20-F or Form 40-F. Form 20-F ☒ Form 40-F ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is submitting the Form 6-K in paper as permitted by Regulation S-T Rule 101(b)(1): ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is submitting the Form 6-K in paper as permitted by Regulation S-T Rule 101(b)(7): ☐ The information contained in this Form 6-K is incorporated by reference into the Company’s Form S-8 Registration Statements File Nos. 333-223678 and 333-219440 and related Prospectuses, as such Registration Statements and Prospectuses may be amended from time to time. British American Tobacco p.l.c. (the “Company” or “BAT”) is furnishing herewith revised financial statements in their entirety and other affected financial information which supersede the equivalent information included in the Company’s Annual Report on Form 20-F for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2017, as filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) on March 15, 2018 (the “Form 20-F”). -

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 6/18/10

Directory of Fire Safe Certified Cigarette Brand Styles Updated 6/18/10 Beginning August 1, 2008, only the cigarette brands and styles listed below are allowed to be imported, stamped and/or sold in the State of Alaska. Per AS 18.74, these brands must be marked as fire safe on the packaging. The brand styles listed below have been certified as fire safe by the State Fire Marshall, bear the "FSC" marking. There is an exception to these requirements. The new fire safe law allows for the sale of cigarettes that are not fire safe and do not have the "FSC" marking as long as they were stamped and in the State of Alaska before August 1, 2008 and found on the "Directory of MSA Compliant Cigarette & RYO Brands." Filter/ Non- Brand Style Length Circ. Filter Pkg. Descr. Manufacturer 1839 Blue 100 Box 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Blue King Box 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 82.7 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 97 24.60 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Full Flavor 83 24.60 Non-Filter Soft Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 83 24.40 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Light 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. Flue-Cured Tobacco Growers, Inc. 1839 Menthol 97 24.50 Filter Hard Pack U.S. -

Page 1 of 15

Updated September14, 2021– 9:00 p.m. Date of Next Known Updates/Changes: *Please print this page for your own records* If there are any questions regarding pricing of brands or brands not listed, contact Heather Lynch at (317) 691-4826 or [email protected]. EMAIL is preferred. For a list of licensed wholesalers to purchase cigarettes and other tobacco products from - click here. For information on which brands can be legally sold in Indiana and those that are, or are about to be delisted - click here. *** PLEASE sign up for GovDelivery with your EMAIL and subscribe to “Tobacco Industry” (as well as any other topic you are interested in) Future lists will be pushed to you every time it is updated. *** https://public.govdelivery.com/accounts/INATC/subscriber/new RECENTLY Changed / Updated: 09/14/2021- Changes to LD Club and Tobaccoville 09/07/2021- Update to some ITG list prices and buydowns; Correction to Pall Mall buydown 09/02/2021- Change to Nasco SF pricing 08/30/2021- Changes to all Marlboro and some RJ pricing 08/18/2021- Change to Marlboro Temp. Buydown pricing 08/17/2021- PM List Price Increase and Temp buydown on all Marlboro 01/26/2021- PLEASE SUBSCRIBE TO GOVDELIVERY EMAIL LIST TO RECEIVE UPDATED PRICING SHEET 6/26/2020- ***RETAILER UNDER 21 TOBACCO***(EFF. JULY 1) (on last page after delisting) Minimum Minimum Date of Wholesale Wholesale Cigarette Retail Retail Brand List Manufacturer Website Price NOT Price Brand Price Per Price Per Update Delivered Delivered Carton Pack Premier Mfg. / U.S. 1839 Flare-Cured Tobacco 7/15/2021 $42.76 $4.28 $44.00 $44.21 Growers Premier Mfg.