The Dark Side of Marketing Seemingly “Light” Cigarettes: Successful Images and Failed Fact R W Pollay, T Dewhirst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnational Tobacco Companies in Indonesia

The Indonesia Tobacco Market: Foreign Tobacco Company Growth Indonesia is the world’s third largest cigarette market by volume (excluding China) and there are approximately 57 million smokers in the country.2-3 According to one tobacco company, the Indonesia tobacco market consisting of hand-rolled kreteks, machine-rolled kreteks and white cigarettes was 270 billion sticks with a profit pool of RP 26.5 trillion ($2.95 billion USD) in 2010, an increase of 18% since 2007.1 Additionally, Indonesia’s cigarette retail volume and value are predicted to continue to grow consistently over the next five years.2 Indonesia’s growing cigarette market, large population, high smoking prevalence among men, and highly unregulated market, make the country an attractive business opportunity for international tobacco companies attempting to make up for falling profits in developed markets like the United States and Australia. The powerful presence and nature of transnational tobacco companies (TTCs) in Indonesia Source: BAT investor presentation1 increases the threat of the tobacco industry to public health because the companies’ competitive efforts to reach young consumers and female smokers ultimately increase smoking prevalence in markets where they operate. 4 Since 2005, the Indonesian market has shifted from being solely dominated by local manufacturers to a market where the number one, four and six spots are controlled by TTCs: Philip Morris International-owned Sampoerna, British American Tobacco-owned Bentoel, and KT&G-owned Trisakti respectively. In 2010, the combined market share of these three companies made up almost 40% of the Indonesian market.2 Leading local tobacco companies include Gudang Garam (number two), Djarum (number three) and Najorono Tobacco Indonesia (number five). -

Tobacco in Canada Addressing Knowledge Gaps Important to Tobacco Regulation Environmental Scan – Spring Summer 2020

Tobacco in Canada Addressing Knowledge Gaps Important to Tobacco Regulation Environmental Scan – Spring Summer 2020 September 2020 Physicians for a Smoke-Free Canada 134 Caroline Avenue Ottawa Ontario K1Y 0S9 www.smoke-free.ca psc @ smoke-free.ca 1 | P a g e TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 2 I. Federal Government Activities .......................................................................................................................... 3 a) Policy and Regulation.................................................................................................................................... 3 Public opinion research .................................................................................................................................... 7 Other ................................................................................................................................................................. 7 B) Financial Policy ............................................................................................................................................. 7 II. Monitoring and Surveillance ............................................................................................................................. 9 II. Provincial Government activities (April to September 2020) ......................................................................... 11 Alberta -

Menthol Cigarettes and Smoking Cessation Behaviour: a Review of Tobacco Industry Documents Stacey J Anderson1,2

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PubMed Central Research paper Menthol cigarettes and smoking cessation behaviour: a review of tobacco industry documents Stacey J Anderson1,2 1Department of Social and ABSTRACT The concentration of menthol in tobacco prod- Behavioral Sciences, University Objective To determine what the tobacco industry knew ucts varies according to the product and the flavour of California, San Francisco about menthol’s relation to smoking cessation behaviour. desired, but is present in 90% of all tobacco prod- (UCSF), San Francisco, ‘ ’ ‘ ’ 2 3 California, USA Methods A snowball sampling design was used to ucts, mentholated and non-mentholated . 2Center for Tobacco Control systematically search the Legacy Tobacco Documents Studies in the peer-reviewed academic literature of Research and Education, Library (LTDL) (http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu) between 15 the association of menthol smoking and cessation University of California, San May to 1 August 2010. Of the approximately 11 million have yielded conflicting findings. One reason for Francisco (UCSF), San Francisco, California, USA documents available in the LTDL, the iterative searches inconsistencies is differences in study design (eg, returned tens of thousands of results. A final collection of clinical treatment studies, population-based Correspondence to 509 documents relevant to 1 or more of the research studies), and another is differences in cessation Stacey J Anderson, Department questions were qualitatively analysed, as follows: (1) outcomes (eg, length of time abstinent, length of of Social and Behavioral perceived sensory and taste rewards of menthol and time to relapse, number of quit attempts) across Sciences, Box 0612, University fi of California, San Francisco potential relation to quitting; and (2) motivation to quit studies. -

Tobacco Deal Sealed Prior to Global Finance Market Going up in Smoke

marketwatch KEY DEALS Tobacco deal sealed prior to global finance market going up in smoke The global credit crunch which so rocked £5.4bn bridging loan with ABN Amro, Morgan deal. “It had become an auction involving one or Iinternational capital markets this summer Stanley, Citigroup and Lehman Brothers. more possible white knights,” he said. is likely to lead to a long tail of negotiated and In addition it is rescheduling £9.2bn of debt – Elliott said the deal would be part-funded by renegotiated deals and debt issues long into both its existing commitments and that sitting on a large-scale disposal of Rio Tinto assets worth the autumn. the balance sheet of Altadis – through a new as much as $10bn. Rio’s diamonds, gold and But the manifestation of a bad bout of the facility to be arranged by Citigroup, Royal Bank of industrial minerals businesses are now wobbles was preceded by some of the Scotland, Lehmans, Barclays and Banco Santander. reckoned to be favourites to be sold. megadeals that the equity market had been Finance Director Bob Dyrbus said: Financing the deal will be new underwritten expecting for much of the last two years. “Refinancing of the facilities is the start of a facilities provided by Royal Bank of Scotland, One such long awaited deal was the e16.2bn process that is not expected to complete until the Deutsche Bank, Credit Suisse and Société takeover of Altadis by Imperial Tobacco. first quarter of the next financial year. Générale, while Deutsche and CIBC are acting as Strategically the Imps acquisition of Altadis “Imperial Tobacco only does deals that can principal advisors on the deal with the help of has been seen as the must-do in a global generate great returns for our shareholders and Credit Suisse and Rothschild. -

Oh for a New Risorgimento

SPECIAL REPORT I TA LY June 11th 2011 Oh for a new risorgimento SRitaly.indd 1 31/05/2011 14:42 S PECIAL REPORT I TALY O h for a new risorgimento Italy needs to stop blaming the dead for its troubles and get on with life, says John Prideaux ON A WARM spring morning in Treviso, a town in Italy’s north•east, sev• eral hundred people have gathered in the main square, in the shadow of a13th•century bell tower, to listen to speeches. The crowd is so uniformly dressed, in casually smart clothes and expensive sunglasses, that an out• sider might assume invitations to this event had been sent out weeks ago. Most people are clutching plastic ags on white sticks. Some of them car• ry children wearing rosettes in red, white and green. On a temporary stage a succession of speakers talk about the country’s glori• ous history. Italy has taken the day o to celebrate its 150th anniversary as a nation. Treviso’s mayor, Gian Paolo Gobbo, is not celebrating. The desk in his oce faces a large painting of Venice in the style of Canaletto. This has some signicance for Mr Gobbo, who has spent his political career ghting to resus• citate the Republic of Venice, which nally expired in 1797 after a long illness. Below the painting stands a uorescent• green bear. It’s just like me! exclaims the mayor, a portly man in his 60s. Green is the colour of the Northern League, C ONTENTS a party which has sometimes toyed with the idea of break• 3 The economy ing up Italy and allowing the northern part of the country For ever espresso to go it alone. -

Smoke-Free Ontario Strategy Monitoring Report | Pro-Tobacco Influences

Smoke-Free Ontario Strategy Monitoring Report: Pro-Tobacco Influences Smoke-Free Ontario Strategy Monitoring Report | Pro-Tobacco Influences Table of Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................... 3 List of Figures .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Pro-Tobacco Influences ............................................................................................................................... 4 Price and Taxation .................................................................................................................................. 5 Illicit Sales ................................................................................................................................................ 7 Agriculture and Production................................................................................................................... 10 Number of Farms and Production .................................................................................................... 11 Distribution and Consumption ............................................................................................................. 13 Availability ............................................................................................................................................. 14 Tobacco Retail-Free Areas ............................................................................................................... -

British American Tobacco's Submission to the WHO's

British American Tobacco’s submission to the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control This is the submission of the British American Tobacco group of companies commenting on the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. We are the world’s most international tobacco group with an active presence in 180 countries. Our companies sell some of the world’s best known brands including Dunhill, Kent, State Express 555, Lucky Strike, Benson & Hedges, Rothmans and Pall Mall. Executive summary • The WHO’s proposed ‘Framework Convention on Tobacco Control’ is fundamentally flawed and will not achieve its objectives. • The tobacco industry, along with other industries involved in the manufacture and distribution of legal but risky products, is the subject of considerable public attention. It is important that the debate about tobacco remains open, objective, constructive and free from opportunistic criticism if we are effectively to address the real issues associated with tobacco. • British American Tobacco is responsible tobacco. We seek to operate in partnership with governments, who are significant stakeholders in our business, and other interested parties, based on our open acknowledgement that we make a risky product and therefore support sensible regulation. • British American Tobacco shares the World Health Organisation’s desire to reduce the health impact of tobacco use. This paper outlines British American Tobacco’s proposal for the sensible regulation of tobacco. • Our proposal will relieve the WHO of the cost and bureaucracy involved in its wish to become a single global tobacco regulator, leaving it free to do what it should be doing – policy orientation. Some facts about tobacco • Today over one billion adults, about one third of the world’s adult population, choose to smoke. -

PM 12.31.2014 Form 10K Wrap (Incl F/S & MD&A)

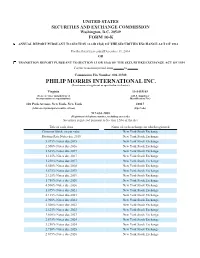

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2014 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-33708 PHILIP MORRIS INTERNATIONAL INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Virginia 13-3435103 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 120 Park Avenue, New York, New York 10017 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) 917-663-2000 (Registrant’s telephone number, including area code) Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, no par value New York Stock Exchange Floating Rate Notes due 2015 New York Stock Exchange 5.875% Notes due 2015 New York Stock Exchange 2.500% Notes due 2016 New York Stock Exchange 1.625% Notes due 2017 New York Stock Exchange 1.125% Notes due 2017 New York Stock Exchange 1.250% Notes due 2017 New York Stock Exchange 5.650% Notes due 2018 New York Stock Exchange 1.875% Notes due 2019 New York Stock Exchange 2.125% Notes due 2019 New York Stock Exchange 1.750% Notes due 2020 New York Stock Exchange 4.500% Notes due 2020 New York Stock Exchange 1.875% Notes due 2021 New York Stock Exchange 4.125% Notes due 2021 New York Stock Exchange 2.900% Notes due 2021 New York Stock Exchange -

Local Business Database Local Business Database: Alphabetical Listing

Local Business Database Local Business Database: Alphabetical Listing Business Name City State Category 111 Chop House Worcester MA Restaurants 122 Diner Holden MA Restaurants 1369 Coffee House Cambridge MA Coffee 180FitGym Springfield MA Sports and Recreation 202 Liquors Holyoke MA Beer, Wine and Spirits 21st Amendment Boston MA Restaurants 25 Central Northampton MA Retail 2nd Street Baking Co Turners Falls MA Food and Beverage 3A Cafe Plymouth MA Restaurants 4 Bros Bistro West Yarmouth MA Restaurants 4 Family Charlemont MA Travel & Transportation 5 and 10 Antique Gallery Deerfield MA Retail 5 Star Supermarket Springfield MA Supermarkets and Groceries 7 B's Bar and Grill Westfield MA Restaurants 7 Nana Japanese Steakhouse Worcester MA Restaurants 76 Discount Liquors Westfield MA Beer, Wine and Spirits 7a Foods West Tisbury MA Restaurants 7B's Bar and Grill Westfield MA Restaurants 7th Wave Restaurant Rockport MA Restaurants 9 Tastes Cambridge MA Restaurants 90 Main Eatery Charlemont MA Restaurants 90 Meat Outlet Springfield MA Food and Beverage 906 Homwin Chinese Restaurant Springfield MA Restaurants 99 Nail Salon Milford MA Beauty and Spa A Child's Garden Northampton MA Retail A Cut Above Florist Chicopee MA Florists A Heart for Art Shelburne Falls MA Retail A J Tomaiolo Italian Restaurant Northborough MA Restaurants A J's Apollos Market Mattapan MA Convenience Stores A New Face Skin Care & Body Work Montague MA Beauty and Spa A Notch Above Northampton MA Services and Supplies A Street Liquors Hull MA Beer, Wine and Spirits A Taste of Vietnam Leominster MA Pizza A Turning Point Turners Falls MA Beauty and Spa A Valley Antiques Northampton MA Retail A. -

TRACEY A. MASH and ANJANETTA LINGARD Plaintiffs V. BROWN

TRACEY A. MASH and ANJANETTA LINGARD Plaintiffs v. BROWN & WILLIAMSON TOBACCO CORPORATION Defendant UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MISSIOURI (ST. LOUIS) Case No. 4:03CV00485TCM September 20, 2004 PURPOSE This backgrounder has been prepared by some the defendant in this case to provide a concise reference document on the case of Tracey A. Mash and Anjanetta Lingard v. Brown & Williamson Corporation, No. 4:03CV00485TCM. It is not a court document. THE PLAINTIFFS: This lawsuit was filed by Tracey A. Mash and Anjanetta Lingard on March 6, 2003 in state court in Missouri. It was later removed to federal court. The plaintiffs are the daughters of Stella Hale who died on Aug. 16, 2001. Plaintiffs allege Ms. Hale died from lung cancer caused by KOOL cigarettes. THE DEFENDANTS: The sole defendant is Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation (B&W), formerly headquartered in Louisville, Ky. Its major brands included Pall Mall, KOOL, GPC, Carlton, Lucky Strike and Misty. As of July 31, 2004, Brown & Williamson’s domestic tobacco business merged with R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, a New Jersey corporation, to form R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, a North Carolina corporation (“RJRT”). RJRT, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Reynolds American, Inc., is headquartered in Winston-Salem, N.C. It is the nation’s second largest manufacturer of cigarettes. Its brands include those of the former B&W as well as Winston, Salem, Camel and Doral. B&W is represented by Andrew R. McGaan of Kirkland & Ellis, LLP, in Chicago; Fred Erny of Dinsmore & Shohl in Cincinnati, Ohio; and Frank Gundlach of Armstrong Teasdale in St. -

Demystifying the Number of the Beast in the Book of Revelation: Examples of Ancient Cryptology and the Interpretation of the “666” Conundrum

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Engineering and Information Faculty of Informatics - Papers (Archive) Sciences 2010 Demystifying the number of the beast in the book of revelation: examples of ancient cryptology and the interpretation of the “666” conundrum M G. Michael University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers Part of the Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Michael, M G.: Demystifying the number of the beast in the book of revelation: examples of ancient cryptology and the interpretation of the “666” conundrum 2010. https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers/3585 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Demystifying the number of the beast in the book of revelation: examples of ancient cryptology and the interpretation of the “666” conundrum Abstract As the year 2000 came and went, with the suitably forecasted fuse-box of utopian and apocalyptic responses, the question of "666" (Rev 13:18) was once more brought to our attention in different ways. Biblical scholars, for instance, focused again on the interpretation of the notorious conundrum and on the Traditionsgeschichte of Antichrist. For some of those commentators it was a reply to the outpouring of sensationalist publications fuelled by the millennial mania. This paper aims to shed some light on the background, the sources, and the interpretation of the “number of the beast”. It explores the ancient techniques for understanding the conundrum including: gematria, arithmetic, symbolic, and riddle-based solutions. -

Transforming Our Business

Transforming our business A cigarette manufacturing line (on the left-hand side) and a heated tobacco unit manufacturing line (on the right-hand side) at our factory in Neuchâtel, Switzerland Replacing cigarettes with While several attempts have been made to develop better alternatives to smoking, smoke-free products drawbacks in the technological capability of these products and a lack of consumer In 2017, PMI manufactured and shipped acceptance rendered them unsuccessful. 791 billion cigarettes and other Recent advances in science and combustible tobacco products and technology have made it possible to 36 billion smoke‑free products, reaching develop innovative products that approximately 150 million adult consumers consumers accept and that are less in more than 180 countries. harmful alternatives to continued smoking. Smoking cigarettes causes serious PMI has developed a portfolio of disease. Smokers are far more likely smoke‑free products, including heated Contribution of Smoke-Free than non‑smokers to get heart disease, tobacco products and nicotine‑containing Products to PMI’s Total lung cancer, emphysema, and other e‑vapor products that have the potential diseases. Smoking is addictive, and it Net Revenues to significantly reduce individual risk and 13% can be very difficult to stop. population harm compared to cigarettes. The best way to avoid the harms of Many stakeholders have asked us about smoking is never to start, or to quit. the role of these innovative smoke‑free But much more can be done to improve products in the context of our business the health and quality of life of those vision. Are these products an extension of who continue to use nicotine products, our cigarette product portfolio? Are they through science and innovation.