Diplomatic and Consular Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inviolability of Diplomatic Archives

THE INVIOLABILITY OF DIPLOMATIC ARCHIVES TIMMEDIATELY following Pearl Harbor, officials of the em- A bassy of the United States at Tokyo and of the Japanese embassy Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/8/1/26/2742083/aarc_8_1_k010662414m87w48.pdf by guest on 25 September 2021 at Washington destroyed their confidential diplomatic records. American Ambassador Joseph C. Grew asserted, "The moment we knew that the news of war had been confirmed I gave orders to burn all our codes and confidential correspondence."1 Huge bonfires which emanated from the grounds of the Japanese embassy at Wash- ington served as dramatic evidence that the Japanese treated their important archives similarly.2 These actions illustrate that modern states are unwilling to entrust their vital documents to the diplomatic representatives of neutral governments at the outbreak of war, even though international law and practice dictate that records so de- posited are inviolate. Such an attitude stimulates an inquiry into the extent to which diplomatic archives are considered inviolable under international law and the extent to which the principles of interna- tional law are being observed. This subject has never been adequately investigated by scholars, although it is a matter of definite im- portance to the international lawyer and diplomat on the one hand, and the historian and the archivist on the other. What are diplomatic archives? For the purposes of this paper diplomatic archives are defined as the written evidences of the -

Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic

Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Robert J. Bookmiller Gulf Research Center i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Dubai, United Arab Emirates (_}A' !_g B/9lu( s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ *_D |w@_> TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B uG_GAE#'c`}A' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB9f1s{5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'cAE/ i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBª E#'Gvp*E#'B!v,¢#'E#'1's{5%''tDu{xC)/_9%_(n{wGLi_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uAc8mBmA' , ¡dA'E#'c>EuA'&_{3A'B¢#'c}{3'(E#'c j{w*E#'cGuG{y*E#'c A"'E#'c CEudA%'eC_@c {3EE#'{4¢#_(9_,ud{3' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBB`{wB¡}.0%'9{ymA'E/B`d{wA'¡>ismd{wd{3 *4#/b_dA{w{wdA'¡A_A'?uA' k pA'v@uBuCc,E9)1Eu{zA_(u`*E @1_{xA'!'1"'9u`*1's{5%''tD¡>)/1'==A'uA'f_,E i_m(#ÆA Gulf Research Center 187 Oud Metha Tower, 11th Floor, 303 Sheikh Rashid Road, P. O. Box 80758, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Tel.: +971 4 324 7770 Fax: +971 3 324 7771 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.grc.ae First published 2009 i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Gulf Research Center (_}A' !_g B/9lu( Dubai, United Arab Emirates s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ © Gulf Research Center 2009 *_D All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in |w@_> a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Gulf Research Center. -

List of Delegations to the Seventieth Session of the General Assembly

UNITED NATIONS ST /SG/SER.C/L.624 _____________________________________________________________________________ Secretariat Distr.: Limited 18 December 2015 PROTOCOL AND LIAISON SERVICE LIST OF DELEGATIONS TO THE SEVENTIETH SESSION OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY I. MEMBER STATES Page Page Afghanistan......................................................................... 5 Chile ................................................................................. 47 Albania ............................................................................... 6 China ................................................................................ 49 Algeria ................................................................................ 7 Colombia .......................................................................... 50 Andorra ............................................................................... 8 Comoros ........................................................................... 51 Angola ................................................................................ 9 Congo ............................................................................... 52 Antigua and Barbuda ........................................................ 11 Costa Rica ........................................................................ 53 Argentina .......................................................................... 12 Côte d’Ivoire .................................................................... 54 Armenia ........................................................................... -

Pdaba072.Pdf

AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT PPC/CDIE/DI REPORT PROCESSING FORM ENTER INFORMATION ONLY NOT INCLUDED ON COVER OR TITLE PAGE 0"OCUMENT /1. Project/Subproject Number Contract /Grant Number Publication Date 4. Document Title Tanslated Title LL 5. Author(s) 6. Contributing Organization(3) 7 Pagnation 8. Report Number , Sponsoring A.I.D. Office 1W3Abstract (optional - 250 word limit) I1. Sub-.ct Keywords(optional) :1 4. 5. 3. 6. 12. Supplementary No.es 13.Submitting Official 14. Telephone Number !5. Today's Date .................................... DO NOT write below this line ................... ......................... if- DOCID 17. Document Disposition CRD INV DUPLICATE A\ID 590-7 (10/88) bM EPI Technical Assistance to CCCD/Guinea July 16- September 24, 1986 Resources for Child Health Project RA John Snow, Inc. REC H0- 1100 Wilson Boulevard, 9th Floor RArlington, VA 22209 USA Telex: 272896 JSIW UR Telephone: (703) 528-7474 EPI TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE TO CCCD/GUINEA July 16 - September 24, 1986 Submitted by: Harry Godfrey, Consultant THE RESOURCES FOR CHILD HEALTH PROJECT 1100 Wilson Boulevard Ninth Floor Arlington, VA 22209 AID Contract No: DPE-5927-C-00-5068-00 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ACRONYMS ii I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................... 1 II. PURPOSE OF VISIT ..................................................... 4 III. BACKGROUND ........................................................... 4 A. General ......................................................... 4 B. Target Diseases ................................................ -

Sir Anthony Eden and the Suez Crisis of 1956 the Anatomy of a Flawed Personality

Sir Anthony Eden and the Suez Crisis of 1956 The Anatomy of a Flawed Personality by Eamon Hamilton A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of Master of Arts by Research Centre for Byzantine Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies Department of Classics Ancient History and Archeology College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham June 2015 1 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Acknowledgements I am very grateful to the staff at the following institutions: The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford Churchill College Library, University of Cambridge Cadbury Research Library, University of Birmingham Manx National Heritage, Douglas, Isle of Man The National Archives, Kew 2 When Anthony Eden became British Prime Minister on 6 April 1955 it seemed the culmination of a brilliant career in politics. Less than two years later that career was over, effectively destroyed by his behaviour over the nationalisation of the Suez Canal Company by the Egyptian President, Gamal Nasser. -

N. K Times Writer Seen of 'Huge Haax^In Spain Book

'i " "f"lpau »-«M»*riWM3«^,HrtK- ^'*)Hr^^^«f,**f+*' )| j^»i^S,i^aiji»,»Ba4--.«<eaCi!». ~*.*i*K£tv$Ar WW <E-CVM>"' «£«> • ffjar«««W»Ww—t* -.•^»^«H^tf Wot^*«^ ^r*-Brwn«jMrn4tt«*»Tinw**' {* »#-"<*-~ /-, f -^ * * *~* * !" s * * i- „ S trf-H * Li The Alcazar Will Not Surrender! THE CATHOUC .» *i ^ N. K Times Writer Seen OfflCIAL NEWSPAPER OF THE ROCHESTER DIOCESE iVjfjb-fyziritrift-tn 68th Year Rochester, N. Y., FRIDAY, JULY 26, 1957 10 Cents 4 I Bishop 25 Years Of 'Huge Haax^In Spain Book I 5afaTO*n»aJi*k\.1w^ Albany — (Special) — A new book on Spain by New Yoke and the Arrows," a book so full of distortiohs^ewori York Times correspondent Herbert L. Matthews is labelled Cardinal Spellman and contradictions that the Spaniards, consider ifi-'mAglpBk^ <**?*"* a "huge hoax" and chargred with presenting Communist s upon their "honor, courage0 J|8[^^s»fe-^f«r d^^"for propaganda according to a front page story in the current liberte" ^t^^*******„OTiKaa»»:0*-™ *" issue of The Evangelist, Albany diocesan weekly Matthews' pi'kcipa4-«ssauitis laSncIied"ag*ainst the saga To Mark Jubilee 2t^fl^stfcfii^e^r^f'!esls follows; of liie Alcazar of Toledo, one of the most significant feats of -\w York — (NC) —Plans to celebrate the 25th anni-., •In an attempt to reverse the verdiet of nistoiy and can Spanish history-which represents forever the courage of 'Na versary of the Episcopal consecration of Cafdrml Spellman' eel out both. Franco's vfclory and its effects on Spain, Her tionalists., and tJie_^aja^erx---Oi-Bfiuy^oj);ali3t methods. -

Colonial Representation in the Nineteenth Century

81 COLONIAL REPRESENTATION IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY PART II Some Queensland and Other Australian Agents-General [By CLEM LACK, B.A., Dip.Jour., F.R.Hist.S.Q.] (Read at a meeting of the Society on 24 February 1966.) PracticaUy the only guide received by the Colonial Agent- General in enabUng him to carry out his duties in accordance with Government policy were the informal interviews and discussions he would have with the Premier, Treasurer, and other Cabinet Ministers before his departure for England. He would receive with every mail steamer voluminous correspon dence detaUing specific items of Colonial business, contracts, etc., which he was required to attend to. Where there was understanding and confidence between the Agent-General and his superiors in the Colonial Secretary's office this loose arrangement worked reasonably well, but problems were created and friction arose where the Agent-General's title to office was couched in vague and indefinite terms. That unfortunate situation arose early in the history of the Agent-Generalship in Queensland. Both Henry Jordan, Queensland's first Agent-General, and his successor, John Douglas, clashed with the Colonial Secretary and Government of the day, and in each instance much controversial corres pondence resulted regarding the interpretation and scope of their duties. Both men were sternly rebuked for allegedly exceeding their authority. A study of the relevant correspon dence reveals a censorious, pettifogging, and unreasonable attitude by the respective Colonial Secretaries, Herbert, Mac kenzie, and Palmer, and an inability to understand and appre ciate the problems which faced the Agent-General in London, especiaUy in connection with emigration. -

Today, I'm Very Pleased to Get Together with My Friends Here to Celebrate

Speech by H. E. Mr. Cheng Wenju, Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the People’s Republic of China to the Republic of Sierra Leone at the Symposium to Mark the 35th Anniversary of the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations between China and Sierra Leone (July 28, 2006) Hon. Chairman, Hon. Vice President Mr. Solomon Berewa, Hon. Cabinet Ministers and Members of Parliament, Members of the Diplomatic Corp and International Organizations, Representatives of the Chinese Community in Sierra Leone, Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen, Today, I’m very pleased to get together with my friends here to celebrate the 35th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of Sierra Leone. First of all, please allow me to extend to Hon. Vice President Mr. Solomon Berewa and every distinguished friend here the sincere greetings and best wishes from the Chinese government and people. I would also like to take this opportunity to express my heartfelt thanks to those who participated in the preparation for this symposium, particularly the task force consisting of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, Sierra Leone-China Friendship Society, and the Chinese Embassy. On July 29th, 1971, China and Sierra Leone formally established diplomatic ties. Since then, the relations between our two countries have been developing steadily. Hon. Resident Minister of East Province Mr. Fillie-Faboe has witnessed the historically significant occasion of signing the documents for the establishment of diplomatic relations. After listening to his vivid retrospection on this important event and the excellent speech by the former Minister Mr. -

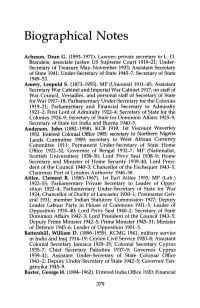

Biographical Notes

Biographical Notes Acheson, Dean G. (1893-1971). Lawyer; private secretary to L. D. Brandeis; associate justice US Supreme Court 1919-21; Und er Secretary of Treasury May-November 1933; Assistant Secretary of State 1941; Under-Secretary of State 1945-7; Secretary of State 1949-53. Amery, Leopold S. (1873-1955). MP (Unionist) 1911-45; Assistant Secretary War Cabinet and Imperial War Cabinet 1917; on staff of War Council, Versailles, and personal staff of Secretary of State for War 1917-18; Parliamentary Under-Secretary for the Colonies 1919-21; Parliamentary and Financial Secretary to Admiralty 1921-2; First Lord of Admiralty 1922-4; Secretary of State for the Colonies 1924-9; Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs 1925-9; Secretary of State for India and Burma 1940-5. Anderson, John (1882-1958). KCB 1919, 1st Viscount Waverley 1952. Entered Colonial Office 1905; secretary to Northem Nigeria Lands Committee 1909; secretary to West African Currency Committee 1911; Permanent Under-Secretary of State Horne Office 1922-32; Governor of Bengal 1932-7; MP (Nationalist, Scottish Universities) 1938-50; Lord Privy Seal 1938-9; Horne Secretary and Minister of Horne Security 1939-40; Lord Presi dent of the Counci11940-3; Chancellor of the Exchequer 1943-5; Chairman Port of London Authority 1946-58. Attlee, Clement R. (1883-1967). 1st Earl Attlee 1955; MP (Lab.) 1922-55; Parliamentary Private Secretary to Leader of Oppo sition 1922-4; Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for War 1924; Chancellor of Duchy of Lancaster 1930-1; Postmaster Gen eral 1931; member Indian Statutory Commission 1927; Deputy Leader Labour Party in House of Commons 1931-5; Leader öf Opposition 1935-40; Lord Privy Seal 1940-2; Secretary of State Dominion Affairs 1942-3; Lord President of the CounciI1943-5; Deputy Prime Minister 1942-5; Prime Minister 1945-51; Minister of Defence 1945-6; Leader of Opposition 1951-5. -

Ad Hoc Diplomats

SCOVILLE IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 1/17/2019 5:24 PM AD HOC DIPLOMATS RYAN M. SCOVILLE† ABSTRACT Article II of the Constitution grants the president power to appoint “Ambassadors” and “other public Ministers” with the advice and consent of the Senate. By all accounts, this language requires Senate confirmation for the appointment of resident ambassadors and other diplomats of similar rank and tenure. Yet these are hardly the only agents of U.S. foreign relations. Ad hoc diplomats—individuals chosen exclusively by the president to complete limited and temporary assignments—play a comparably significant role in addressing international crises, negotiating treaties, and otherwise executing foreign policy. This Article critically examines the appointments process for such irregular agents. An orthodox view holds it permissible for the president to dispatch any ad hoc diplomat without Senate confirmation, but this view does not accord with the original meaning of Article II. Scrutinizing text and an extensive collection of original historical sources, I show that, under a formalist reading of the Constitution, the appointment of most ad hoc diplomats requires the advice and consent of the Senate because these agents are typically “public Ministers” and “Officers of the United States” under the Appointments Clause. The analysis makes several contributions. First, it provides the first thorough account of the original meaning of “public Ministers”—a term that appears several times in the Constitution but lacks precise contours in contemporary scholarship and practice. Second, for formalists, the analysis reorients longstanding debates about the process of treaty-making and empowers the Senate to exert greater influence over a wide variety of presidential initiatives, including communications with North Korea, the renegotiation of trade agreements, the campaign to defeat ISIS, and the stabilization of Ukraine, all of which have relied on the work of ad hoc diplomats. -

Department of Campus Ministry Annual Report 2014-2015

DEPARTMENT OF CAMPUS MINISTRY ANNUAL REPORT 2014-2015 Respectfully submitted by: John B. Scarano, director of Campus Ministry Campus Ministry Philosophy The Department of Campus Ministry encourages students, faculty, and staff of JCU to integrate personal faith into the academic and social environment of the university. We value the university’s commitment to academic pursuits, and welcome the opportunities we have to bring a Catholic and Ignatian faith perspective to bear on issues and trends that may surface in various disciplines and in a variety of social milieus. We have identified the following statements as our purpose: We embrace the Jesuit, Catholic intellectual tradition as an indispensable partner in the search for truth and wisdom. We promote the service of faith and the promotion of justice through education, advocacy, service and reflection; We foster the development of whole persons who become servant leaders in their local and global faith communities. We provide an open, caring, hospitable and collaborative atmosphere that supports the mission of the University. We establish a sense of community through vibrant worship, retreats, small faith communities, and immersion experiences. We recognize Eucharist as our primary liturgical experience, while also celebrating a diversity of faith and spiritual perspectives that seeks both wisdom and a fuller spiritual life. Departmental Goals: In solidarity with the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, we aspire to instill a basic knowledge and understanding of the six aspects of Campus Ministry outlined in the 1985 US Bishop’s Pastoral Letter “Empowered By the Spirit: Campus Ministry Faces the Future.” The six aspects are: Forming the Faith Community Facilitating Personal Development Appropriating the Faith Educating for Justice Forming the Christian Conscience Developing Leaders for the Future In light of these aspects, our departmental goals are as follows: 1. -

ADMINISTRATION of the PRINCE EDWARD ISLANDS [The Following Statement Was Issued by the Commonwealth Relations Office Oh 8 September 1950

276 NOTES AND REVIEWS Letter dated 19 December 1950, from the Resident Minister for Australia in London to the Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations My dear Secretary of State, I have the honour to refer to the letter from the Office of the United Kingdom High Commissioner in the Commonwealth of Australia, dated 23 December 1947, in which His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom confirmed their willingness to transfer to His Majesty's Government in the Commonwealth of Australia their rights in Heard Island and McDonald Islands. In consequence of this communication, effective government, administration and control of these islands were established by the Commonwealth Government on 26 December 1947. Accordingly, the Commonwealth Government for their part understand the position to be that as from that date His Majesty's sovereignty over these islands has been exercised by them and the rights of the United Kingdom Government in the islands have been transferred to them and that, by such transfer and by the establishment of effective Australian government, administration and control, the territory has been acquired by the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth Government would be grateful to learn whether this is also the understanding of His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom. Yours sincerely, [Signed] EKIC J. HARRISON Letter dated 19 December 1950, from the Secretary of State for Commonwealth Relations to the Resident Minister for Australia in London My dear Resident Minister, I have the honour to acknowledge receipt of your