1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modern-Reduction-Methods.Pdf

Modern Reduction Methods Edited by Pher G. Andersson and Ian J. Munslow Related Titles Yamamoto, H., Ishihara, K. (eds.) Torii, S. Acid Catalysis in Modern Electroorganic Reduction Organic Synthesis Synthesis 2008 2006 ISBN: 978-3-527-31724-0 ISBN: 978-3-527-31539-0 Roberts, S. M. de Meijere, A., Diederich, F. (eds.) Catalysts for Fine Chemical Metal-Catalyzed Cross- Synthesis V 5 – Regio and Coupling Reactions Stereo-Controlled Oxidations 2004 and Reductions ISBN: 978-3-527-30518-6 2007 Online Book Wiley Interscience Bäckvall, J.-E. (ed.) ISBN: 978-0-470-09024-4 Modern Oxidation Methods 2004 de Vries, J. G., Elsevier, C. J. (eds.) ISBN: 978-3-527-30642-8 The Handbook of Homogeneous Hydrogenation 2007 ISBN: 978-3-527-31161-3 Modern Reduction Methods Edited by Pher G. Andersson and Ian J. Munslow The Editors All books published by Wiley-VCH are carefully produced. Nevertheless, authors, editors, and Prof. Dr. Pher G. Andersson publisher do not warrant the information Uppsala University contained in these books, including this book, to Department of Organic Chemistry be free of errors. Readers are advised to keep in Husargatan 3 mind that statements, data, illustrations, 751 23 Uppsala procedural details or other items may Sweden inadvertently be inaccurate. Dr. Ian J. Munslow Library of Congress Card No.: Uppsala University applied for Department of Biochemistry and Organic Chemistry Husargatan 3 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data 751 23 Uppsala A catalogue record for this book is available from Sweden the British Library. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at <http://dnb.d-nb.de>. -

Chemistry 0310 - Organic Chemistry 1 Chapter 6

Dr. Peter Wipf Chemistry 0310 - Organic Chemistry 1 Chapter 6. SN2 Reactions Nucleophilic substitution reactions occur when nucleophiles (electron-rich species) displace leaving groups on electrophiles (electron-poor species). The net result is the substitution of one group for another bonded to a carbon atom. Nucleophilicity is increased by a negative charge and an increase in the polarizability. The greater the size and the lower the electronegativity of an atom, the greater its polarizability. Leaving groups are stable species that can be detached with their bonding electrons from a molecule during reaction. Most good leaving groups are the conjugate bases of strong acids. Sulfonates (mesylates, tosylates, triflates, etc.) are popular leaving groups since they can be readily obtained from alcohols. Solvents also influence nucleophilicity. SN2 reactions are second-order reactions whose rates depend o the concentration of both the alkyl halide and the nucleophile. The transition state of the one-step SN2 process involves a trigonal bipyramidal carbon and results in an overall inversion of configuration. The order of reactivity of alkyl halides and alkyl sulfonates in SN2 reactions is CH3>1°>2°>3°. The activation energy, DG‡, determines the rate of a reaction: k = koexp(-DG‡/RT). The overall change in free energy, DG, determines the position of the thermodynamic equilibrium. A positive sign of DG is characteristic for an endergonic reaction, a negative DG is found for an exergonic process. The rate of a reaction can be measured and provides information about its mechanism. The reaction order is the sum of the exponents in the rate equation. Relative Leaving Group Abilities: Leaving Group Common Name krel AcO acetate 1 x 10-10 Cl chloride 0.0001 Br bromide 0.001 I iodide 0.01 O mesylate 1.00 H3C S O O O tosylate 0.70 H3C S O O O brosylate 2.62 Br S O O O nosylate 13 O2N S O O O fluorosulfate 29,000 F S O O O triflate 56,000 CF3 S O O O nonaflate 120,000 C4F9 S O O. -

Leaving Group of Substrate Important

1 Recap... • Last two lectures we looked at substitution reactions • We found that there we two (extreme) mechanisms • SN1 H H H H H PhS R H R Br R SPh Br • And SN2 H H H H PhS + Br R Br PhS R • We looked at many of the factors that influenced which ..mechanism was operating... • Now we will turn our attention to elimination reactions 2 Elimination reactions NaOH NaOH or low Br H2O OH concentration • You have seen SN1 substitution • Reaction not sped up by altering nucleophile - it is not in RDS • In fact if we increase the amount / concentration of nucleophile we get the following... high O H + + + Br Br OH concentration H H • We observe an elimination reaction • Overall HBr is lost from the molecule • Isn't chemistry fun - these are the same conditions as substitution! • Next two lectures will look at the mechanisms for elimination • And how we control the nature of the reaction we observe... 3 Elimination, bimolecular E2 O H Br HO Br H H • E2 - Elimination bimolecular or 2nd order reaction • 2 molecules in the RDS or transition state H H H H H C H C H H C Br Br H O H C H O H C C H H H H C H C H H H • Two molecules in the rate determining step • So both the base and the substrate control the reaction • Both carbon skeleton & leaving group of substrate important In substitutions nucleophile acts as a nucleophile & attacks carbon In eliminations nucleophile acts as a base & attacks proton 4 Elimination, bimolecular E2: MO • Little confusing as need bonding & anti-bonding in same diagram! • Orbitals need to be parallel for maximum overlap -

MODULAR PHOSPHINOOXAZOLINES: SYNTHESIS and EVALUATION in ALLYLIC SUBSTITUTIONS Dana Madeleine Popa ISBN:978-84-691-8862-0/DL:T-1275-2008

UNIVERSITAT ROVIRA I VIRGILI MODULAR PHOSPHINOOXAZOLINES: SYNTHESIS AND EVALUATION IN ALLYLIC SUBSTITUTIONS Dana Madeleine Popa ISBN:978-84-691-8862-0/DL:T-1275-2008 PhD Thesis MODULAR PHOSPHINOOXAZOLINES: SYNTHESIS AND EVALUATION IN ALLYLIC SUBSTITUTIONS Dana Madeleine Popa Tarragona, July 2008 UNIVERSITAT ROVIRA I VIRGILI MODULAR PHOSPHINOOXAZOLINES: SYNTHESIS AND EVALUATION IN ALLYLIC SUBSTITUTIONS Dana Madeleine Popa ISBN:978-84-691-8862-0/DL:T-1275-2008 UNIVERSITAT ROVIRA I VIRGILI MODULAR PHOSPHINOOXAZOLINES: SYNTHESIS AND EVALUATION IN ALLYLIC SUBSTITUTIONS Dana Madeleine Popa ISBN:978-84-691-8862-0/DL:T-1275-2008 Institut Catalá d’Investigació Química Memoria presentada por Dana Madeleine Popa para optar al título de Doctor por la Universitat Rovira i Virgili. Revisada por Dr. Anton Vidal Dr. Miquel A. Pericàs UNIVERSITAT ROVIRA I VIRGILI MODULAR PHOSPHINOOXAZOLINES: SYNTHESIS AND EVALUATION IN ALLYLIC SUBSTITUTIONS Dana Madeleine Popa ISBN:978-84-691-8862-0/DL:T-1275-2008 UNIVERSITAT ROVIRA I VIRGILI MODULAR PHOSPHINOOXAZOLINES: SYNTHESIS AND EVALUATION IN ALLYLIC SUBSTITUTIONS Dana Madeleine Popa ISBN:978-84-691-8862-0/DL:T-1275-2008 El presente trabajo de investigación ha sido realizado en el Institut Català d`Investigació Química, bajo la dirección de Dr. Anton Vidal y al Dr. Miquel A. Pericàs, a quienes les quiero dar las gracias por la oportunidad que me han ofrecido de formarme como investigadora bajo su supervisión. Quiero agradecer a Dr. Anton Vidal por los consejos y ayuda que me ha ofrecido día a día. Agradezco a Dr. Miquel A. Pericàs por el soporte que me ha proporcionado en todo el momento. Quiero agradecer también a Sergi Rodríguez Escrich por su colaboración en una parte del trabajo de investigación realizado. -

N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands for Iridium- Catalysed Asymmetric Hydrogenation

N-Heterocyclic Carbene Ligands for Iridium- Catalysed Asymmetric Hydrogenation Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Basel von Steve Nanchen aus Lens / Schweiz Basel 2005 Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät auf Antrag von: Prof. Dr. Andreas Pfaltz Prof. Dr. Wolf-Dietrich Woggon Basel, den 20. September 2005 Prof. Dr. Hans-Jakob Wirz Dekan to my wife Annik Acknowledgments I thank Professor Andreas Pfaltz to have given me the opportunity of joining his group, for his help and constant support over the last four years. I also thank Professor Wolf-Dietrich Woggon who agreed to co-examine this thesis. Dr. Valentin Köhler, Dr. William Drury III, Dr. Geoffroy Guillemot and Dr. Benoît Pugin, Solvias AG, are acknowledged for helpful discussions and fruitful collaboration. I am grateful to Markus Neuburger and Dr. Silvia Schaffner for recording numerous X-ray data and for refining X-ray structures. Dr. Klaus Kulicke, Axel Franzke and Dr. Clément Mazet are acknowledged for their countless hours recording 2D NMR spectra and their help on interpretation of data. I thank Björn Gschwend, Dominik Frank and Peter Sommer for their laboratory work contributions. Thanks to Dr. Cara Humphrey, Dr. Geoffroy Guillemot and Dr. Yann Ribourdouille for proof-reading the manuscript. A special thanks goes to the members of the Pfaltz group who have made my stay in Basel an enjoyable time. Thanks to lab 204 for the nice working atmosphere. A big thanks to my friends and family. Their help and presence during these four years was invaluable. Finally, thanks to Annik for all her support and love. -

Carbonyl Chemistry I: Additions to Carbonyl Groups

Paul Bracher Chem 30 – Section 4 Carbonyl Chemistry I: Additions to Carbonyl Groups Section Agenda 1) Lessons from Exam I, Course Feedbeck Mechanism on Web Site 2) Carbonyl Groups: Structure, Bonding, Molecular Orbitals, Geometry, Reactivity 3) Handout: In-Section Problem Set 4) Handout: In-Section Solution Set 5) Weekly Office Hours: Thursday, 3-4PM and 8-9PM, in Bauer Lobby Structure and Bonding · Carbonyl carbons are roughly sp2 hybridized Molecular Orbital Picture and planar with bond angles near 120 degrees bonding p orbital antibonding p* orbital · The C=O p bond is formed by the overlap of two unhybridized p orbitals. The bond is polarized due to the different electronegativities of carbon and oxygen. 105 o Resonance Model O O Bürgi-Dunitz angle · Another way to picture carbonyl groups is I II through an MO picture. Since the coefficient of · Resonance form II suggests that the carbon pO’s contribution is greater in pC=O, then atom is surrounded by less negative charge conservation of blending atomic orbitals into density than oxygen, rendering the carbon more molecular orbitals tells you that pC must be a electrophilic. larger contributor to the p*C=O orbital. · When reagents add to carbonyl double bonds, · The larger coefficient on oxygen in the filled the nucleophile attacks the carbon atom. orbital explains why the oxygen atom behaves as a Lewis base (it commonly complexes with · Due to the increased negative charge density Lewis acids). The larger coefficient on carbon on oxygen, Lewis acids (such as protons) in the empty antibonding orbital explains why it commonly complex with oxygen. -

Sulfenylphosphinoferrocenes: Novel Planar Chiral Ligands in Enantioselective Catalysis*

Pure Appl. Chem., Vol. 78, No. 2, pp. 257–265, 2006. doi:10.1351/pac200678020257 © 2006 IUPAC Sulfenylphosphinoferrocenes: Novel planar chiral ligands in enantioselective catalysis* Silvia Cabrera, Olga García Mancheño, Ramón Gómez Arrayás, Inés Alonso, Pablo Mauleón, and Juan C. Carretero‡ Departamento de Química Orgánica, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, 28049 Madrid, Spain Abstract: Structurally well-defined transition-metal complexes of 1-phosphino-2-sulfenyl- ferrocene (Fesulphos ligands) act as highly efficient catalysts in a variety of mechanistically different transformations. Excellent enantioselectivities were achieved in Pd-catalyzed allylic substitutions, desymmetrization of meso-heterobicyclic alkenes by Pd-catalyzed addition of dialkylzinc reagents, Pd-catalyzed Diels–Alder reaction of cyclopentadiene with N-acryloyl oxazolidinones, and in Cu-catalyzed formal aza-Diels–Alder reaction of Danishefsky diene to N-sulfonyl aldimines. Keywords: sulfenylphosphinoferrocenes; Fesulphos; enantioselective; Pd-catalyzed; allylic substitutions; desymmetrization; Danishefsky diene; N-sulfonyl aldimines; Cu-catalyzed. INTRODUCTION Two main structural concepts have proved to be greatly successful in the design of chiral ligands for asymmetric catalysis: The reduction of the possible diastereomeric transition states by using bidentate C2-symmetrical P/P, N/N, or O/O chiral ligands (e.g., BINAP, bisoxazolines, salen, or BINOL-based ligands) and the use of mixed bidentated ligands equipped with strong and weak donor heteroatom pairs [1]. This second strategy takes advantage of the different electronic properties associated with each heteroatom-metal bond (e.g., the trans influence) which, playing in combination with appropriate steric effects around the metal-coordinating heteroatoms, can create an asymmetric environment capable of inducing high levels of enantiocontrol. Some bidentate P/N chiral ligands such as phosphine–oxazoline systems and QUINAP constitute excellent examples of this strategy [2]. -

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Just Like an Alkene, Benzene Has Clouds of Electrons Above and Below Its Sigma Bond Framework

Reactions of Aromatic Compounds Just like an alkene, benzene has clouds of electrons above and below its sigma bond framework. Although the electrons are in a stable aromatic system, they are still available for reaction with strong electrophiles. This generates a carbocation which is resonance stabilized (but not aromatic). This cation is called a sigma complex because the electrophile is joined to the benzene ring through a new sigma bond. The sigma complex (also called an arenium ion) is not aromatic since it contains an sp3 carbon (which disrupts the required loop of p orbitals). Ch17 Reactions of Aromatic Compounds (landscape).docx Page1 The loss of aromaticity required to form the sigma complex explains the highly endothermic nature of the first step. (That is why we require strong electrophiles for reaction). The sigma complex wishes to regain its aromaticity, and it may do so by either a reversal of the first step (i.e. regenerate the starting material) or by loss of the proton on the sp3 carbon (leading to a substitution product). When a reaction proceeds this way, it is electrophilic aromatic substitution. There are a wide variety of electrophiles that can be introduced into a benzene ring in this way, and so electrophilic aromatic substitution is a very important method for the synthesis of substituted aromatic compounds. Ch17 Reactions of Aromatic Compounds (landscape).docx Page2 Bromination of Benzene Bromination follows the same general mechanism for the electrophilic aromatic substitution (EAS). Bromine itself is not electrophilic enough to react with benzene. But the addition of a strong Lewis acid (electron pair acceptor), such as FeBr3, catalyses the reaction, and leads to the substitution product. -

AROMATIC NUCLEOPHILIC SUBSTITUTION-PART -2 Electrophilic Substitution

Dr. Tripti Gangwar AROMATIC NUCLEOPHILIC SUBSTITUTION-PART -2 Electrophilic substitution ◦ The aromatic ring acts as a nucleophile, and attacks an added electrophile E+ ◦ An electron-deficient carbocation intermediate is formed (the rate- determining step) which is then deprotonated to restore aromaticity ◦ electron-donating groups on the aromatic ring (such as -OH, -OCH3, and alkyl) make the reaction faster, since they help to stabilize the electron-poor carbocation intermediate ◦ Lewis acids can make electrophiles even more electron-poor (reactive), increasing the reaction rate. For example FeBr3 / Br2 allows bromination to occur at a useful rate on benzene, whereas Br2 by itself is slow). In fact, a substitution reaction does occur! (But, as you may suspect, this isn’t an electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction.) In this substitution reaction the C-Cl bond breaks, and a C-O bond forms on the same carbon. The species that attacks the ring is a nucleophile, not an electrophile The aromatic ring is electron-poor (electrophilic), not electron rich (nucleophilic) The “leaving group” is chlorine, not H+ The position where the nucleophile attacks is determined by where the leaving group is, not by electronic and steric factors (i.e. no mix of ortho– and para- products as with electrophilic aromatic substitution). In short, the roles of the aromatic ring and attacking species are reversed! The attacking species (CH3O–) is the nucleophile, and the ring is the electrophile. Since the nucleophile is the attacking species, this type of reaction has come to be known as nucleophilic aromatic substitution. n nucleophilic aromatic substitution (NAS), all the trends you learned in electrophilic aromatic substitution operate, but in reverse. -

Alkyl Halides

Alkyl Halides Alkyl halides are a class of compounds where a halogen atom or atoms are bound to an sp3 orbital of an alkyl group. CHCl3 (Chloroform: organic solvent) CF2Cl2 (Freon-12: refrigerant CFC) CF3CHClBr (Halothane: anesthetic) Halogen atoms are more electronegative than carbon atoms, and so the C-Hal bond is polarized. The C-Hal (often written C-X) bond is polarized in such a way that there is partial positive charge on the carbon and partial negative charge on the halogen. Ch06 Alkyl Halides (landscape).docx Page 1 Dipole moment Electronegativities decrease in the order of: F > Cl > Br > I Carbon-halogen bond lengths increase in the order of: C-F < C-Cl < C-Br < C-I Bond Dipole Moments decrease in the order of: C-Cl > C-F > C-Br > C-I = 1.56D 1.51D 1.48D 1.29D Typically the chemistry of alkyl halides is dominated by this effect, and usually results in the C-X bond being broken (either in a substitution or elimination process). This reactivity makes alkyl halides useful chemical reagents. Ch06 Alkyl Halides (landscape).docx Page 2 Nomenclature According to IUPAC, alkyl halides are treated as alkanes with a halogen (Halo-) substituent. The halogen prefixes are Fluoro-, Chloro-, Bromo- and Iodo-. Examples: Often compounds of CH2X2 type are called methylene halides. (CH2Cl2 is methylene chloride). CHX3 type compounds are called haloforms. (CHI3 is iodoform). CX4 type compounds are called carbon tetrahalides. (CF4 is carbon tetrafluoride). Alkyl halides can be primary (1°), secondary (2°) or tertiary (3°). Other types: A geminal (gem) dihalide has two halogens on the same carbon. -

Nitrogen-Based Ligands : Synthesis, Coordination Chemistry and Transition Metal Catalysis

Nitrogen-based ligands : synthesis, coordination chemistry and transition metal catalysis Citation for published version (APA): Caipa Campos, M. A. (2005). Nitrogen-based ligands : synthesis, coordination chemistry and transition metal catalysis. Technische Universiteit Eindhoven. https://doi.org/10.6100/IR594547 DOI: 10.6100/IR594547 Document status and date: Published: 01/01/2005 Document Version: Publisher’s PDF, also known as Version of Record (includes final page, issue and volume numbers) Please check the document version of this publication: • A submitted manuscript is the version of the article upon submission and before peer-review. There can be important differences between the submitted version and the official published version of record. People interested in the research are advised to contact the author for the final version of the publication, or visit the DOI to the publisher's website. • The final author version and the galley proof are versions of the publication after peer review. • The final published version features the final layout of the paper including the volume, issue and page numbers. Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. -

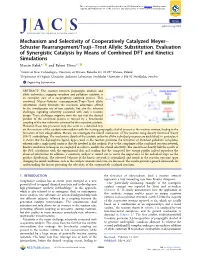

Mechanism and Selectivity of Cooperatively Catalyzed Meyer− Schuster Rearrangement/Tsuji−Trost Allylic Substitution

This is an open access article published under an ACS AuthorChoice License, which permits copying and redistribution of the article or any adaptations for non-commercial purposes. Article pubs.acs.org/JACS Mechanism and Selectivity of Cooperatively Catalyzed Meyer− Schuster Rearrangement/Tsuji−Trost Allylic Substitution. Evaluation of Synergistic Catalysis by Means of Combined DFT and Kinetics Simulations Marcin Kalek*,† and Fahmi Himo*,‡ † Centre of New Technologies, University of Warsaw, Banacha 2C, 02-097 Warsaw, Poland ‡ Department of Organic Chemistry, Arrhenius Laboratory, Stockholm University, S-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden *S Supporting Information ABSTRACT: The reaction between propargylic alcohols and allylic carbonates, engaging vanadium and palladium catalysts, is an exemplary case of a cooperatively catalyzed process. This combined Meyer−Schuster rearrangement/Tsuji−Trost allylic substitution clearly illustrates the enormous advantages offered by the simultaneous use of two catalysts, but also the inherent challenges regarding selectivity associated with such a reaction design. These challenges originate from the fact that the desired product of the combined process is formed by a bimolecular coupling of the two substrates activated by the respective catalysts. However, these two processes may also occur in a detached way via the reactions of the catalytic intermediates with the starting propargylic alcohol present in the reaction mixture, leading to the formation of two side-products. Herein, we investigate the overall mechanism of this reaction using density functional theory (DFT) methodology. The mechanistic details of the catalytic cycles for all the individual processes are established. In particular, it is shown that the diphosphine ligand, dppm, used in the reaction promotes the formation of dinuclear palladium complexes, wherein only a single metal center is directly involved in the catalysis.