William of Pagula's Speculum Religiosorum and Its Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blyth Priory 1

28 SEPTEMBER 2013 BLYTH PRIORY 1 Release Version notes Who date Current version: H1-Blyth-2013-1 28/9/13 Original version RS Previous versions: ———— This text is made available through the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs License; additional terms may apply Authors for attribution statement: Charters of William II and Henry I Project Richard Sharpe, Faculty of History, University of Oxford BLYTH PRIORY Benedictine priory of St Mary; dependency of La Trinité-du-Mont, Rouen County of Nottinghamshire : Diocese of York Founded 1083 × 1086 Roger de Busli received the southernmost of the three great castelries created in Yorkshire in the early 1080s (DB, i. 319r–v; §§ 10. W1–43).1 He was already a benefactor of the abbey of La Trinité-du-Mont near Rouen when, apparently before 1086, he and his wife Muriel chose to transform the church of Blyth into a priory of monks dependent on the Norman abbey.2 Building work on a substantial scale began swiftly: most of the nave of the original priory church survives in an austere early Norman style. The location chosen for the priory lies on a high road north from Nottingham, often referred to in deeds as the uia regia, which connects with the Great North Road.3 Tolls were the main component of its revenues, and the so-called foundation charter in Roger de Busli’s name provides for both holding fairs and receiving tolls (Ctl. Blyth, 208, 1 The others were Pontefract, given to Ilbert de Lacy (DB, i. 315a–318b; §§ 9. W1– 144), who founded a priory at Pontefract (0000), and Richmond, given to Count Alan Rufus (DB, i. -

Download the Catalogue

Five Hundred Years of Fine, Fancy and Frivolous Bindings George bayntun Manvers Street • Bath • BA1 1JW • UK Tel: 01225 466000 • Fax: 01225 482122 Email: [email protected] www.georgebayntun.com BOUND BY BROCA 1. AINSWORTH (William Harrison). The Miser's Daughter: A Tale. 20 engraved plates by George Cruikshank. First Edition. Three volumes. 8vo. [198 x 120 x 66 mm]. vii, [i], 296 pp; iv, 291 pp; iv, 311 pp. Bound c.1900 by L. Broca (signed on the front endleaves) in half red goatskin, marbled paper sides, the spines divided into six panels with gilt compartments, lettered in the second and third and dated at the foot, the others tooled with a rose and leaves on a dotted background, marbled endleaves, top edges gilt. (The paper sides slightly rubbed). [ebc2209]. London: [by T. C. Savill for] Cunningham and Mortimer, 1842. £750 A fine copy in a very handsome binding. Lucien Broca was a Frenchman who came to London to work for Antoine Chatelin, and from 1876 to 1889 he was in partnership with Simon Kaufmann. From 1890 he appears under his own name in Shaftesbury Avenue, and in 1901 he was at Percy Street, calling himself an "Art Binder". He was recognised as a superb trade finisher, and Marianne Tidcombe has confirmed that he actually executed most of Sarah Prideaux's bindings from the mid-1890s. Circular leather bookplate of Alexander Lawson Duncan of Jordanstone House, Perthshire. STENCILLED CALF 2. AKENSIDE (Mark). The Poems. Fine mezzotint frontispiece portrait by Fisher after Pond. First Collected Edition. 4to. [300 x 240 x 42 mm]. -

Constructing 'Race': the Catholic Church and the Evolution of Racial Categories and Gender in Colonial Mexico, 1521-1700

CONSTRUCTING ‘RACE’: THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE EVOLUTION OF RACIAL CATEGORIES AND GENDER IN COLONIAL MEXICO, 1521-1700 _______________ A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Alexandria E. Castillo August, 2017 i CONSTRUCTING ‘RACE’: THE CATHOLIC CHURCH AND THE EVOLUTION OF RACIAL CATEGORIES AND GENDER IN COLONIAL MEXICO, 1521-1700 _______________ An Abstract of a Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History University of Houston _______________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________ By Alexandria E. Castillo August, 2017 ii ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the role of the Catholic Church in defining racial categories and construction of the social order during and after the Spanish conquest of Mexico, then New Spain. The Catholic Church, at both the institutional and local levels, was vital to Spanish colonization and exercised power equal to the colonial state within the Americas. Therefore, its interests, specifically in connection to internal and external “threats,” effected New Spain society considerably. The growth of Protestantism, the Crown’s attempts to suppress Church influence in the colonies, and the power struggle between the secular and regular orders put the Spanish Catholic Church on the defensive. Its traditional roles and influence in Spanish society not only needed protecting, but reinforcing. As per tradition, the Church acted as cultural center once established in New Spain. However, the complex demographic challenged traditional parameters of social inclusion and exclusion which caused clergymen to revisit and refine conceptions of race and gender. -

THE UNIVERSITY of HULL John De Da1derby

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL John de Da1derby, Bishop 1300 of Lincoln, - 1320 being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Hull by Clifford Clubley, M. A. (Leeds) March, 1965 r' ý_ý ki "i tI / t , k, CONTENTS Page 1 Preface """ """ """ """ """ Early Life ... ... ... ... ... 2 11 The Bishop's Household ... ... ... ... Diocesan Administration ... ... ... ... 34 Churches 85 The Care of all the . ... ... ... Religious 119 Relations with the Orders. .. " ... Appendices, Dalderby's 188 A. Itinerary ... ... B. A Fragment of Dalderby's Ordination Register .. 210 C. Table of Appointments ... ... 224 ,ý. ý, " , ,' Abbreviations and Notes A. A. S. R. Reports of the Lincolnshire Associated architectural Archaeological Societies. and Cal. Calendar. C. C. R. Calendar of Close Rolls C. P. R. Calendar of Patent Rolls D&C. Dean and Chapter's Muniments E. H. R. English History Review J. E. H. Journal of Ecclesiastical History L. R. S. Lincoln Record Society O. H. S. Oxford Historical Society Reg. Register. Reg. Inst. Dalderby Dalderby's Register of Institutions, also known as Bishopts Register No. II. Reg. Mem. Dalderby Dalderby's Register of Memoranda, or Bishop's Register No. III. The folios of the Memoranda Register were originally numbered in Roman numerals but other manuscripts were inserted Notes, continued when the register was bound and the whole volume renumbered in pencil. This latter numeration is used in the references given in this study. The Vetus Repertorium to which reference is made in the text is a small book of Memoranda concerning the diocese of Lincoln in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. The original is in the Cambridge University Library, No. -

Marren Akoth AWITI, IBVM Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Canon

FORMATION OF WOMEN RELIGIOUS DURING THE PERIOD OF TEMPORARY VOWS WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO THE RELIGIOUS INSTITUTE OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY (LORETO SISTERS) Marren Akoth AWITI, IBVM Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Canon Law, Saint Paul University, Ottawa, Canada, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Canon Law Faculty of Canon Law Saint Paul University ©Marren Akoth AWITI, Ottawa, Canada, 2017 ii ABSTRACT The Church instructs that the formation of religious after first profession, already begun in the novitiate, is to be perfected so that they may acquire the necessary maturity to lead the life of the institute more fully and to carry out its mission more effectively, mindful of the needs of the Church, mission of the institute and condition of people and times (c. 659 § 1). Formation after first profession for non-clerical religious is an innovation of Vatican II. The document Renovationis causam recognizes the necessity and significance of post-novitiate formation in helping the temporarily professed religious attain the required growth towards maturity necessary for permanent commitment. With the promulgation of the 1983 Code of Canon Law, post-novitiate formation is accorded formal legislation and recognized as an intrinsic aspect of religious life. The Code specifies its aims, dimensions and pedagogy, leaving its structure and duration to be designed by individual institutes. The Church requires that each institute draw up a ratio which is structured according to the provisions of universal norms at the same time allowing some latitude for necessary adaptations of aspects which may require revision. Despite the provisions specified in the universal law, together with further directives given in subsequent Holy See documents, formation of religious continues to be a constant challenge to the Church as well as religious institutes. -

Timeline1800 18001600

TIMELINE1800 18001600 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 8000BCE Sharpened stone heads used as axes, spears and arrows. 7000BCE Walls in Jericho built. 6100BCE North Atlantic Ocean – Tsunami. 6000BCE Dry farming developed in Mesopotamian hills. - 4000BCE Tigris-Euphrates planes colonized. - 3000BCE Farming communities spread from south-east to northwest Europe. 5000BCE 4000BCE 3900BCE 3800BCE 3760BCE Dynastic conflicts in Upper and Lower Egypt. The first metal tools commonly used in agriculture (rakes, digging blades and ploughs) used as weapons by slaves and peasant ‘infantry’ – first mass usage of expendable foot soldiers. 3700BCE 3600BCE © PastSearch2012 - T i m e l i n e Page 1 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 3500BCE King Menes the Fighter is victorious in Nile conflicts, establishes ruling dynasties. Blast furnace used for smelting bronze used in Bohemia. Sumerian civilization developed in south-east of Tigris-Euphrates river area, Akkadian civilization developed in north-west area – continual warfare. 3400BCE 3300BCE 3200BCE 3100BCE 3000BCE Bronze Age begins in Greece and China. Egyptian military civilization developed. Composite re-curved bows being used. In Mesopotamia, helmets made of copper-arsenic bronze with padded linings. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, first to use iron for weapons. Sage Kings in China refine use of bamboo weaponry. 2900BCE 2800BCE Sumer city-states unite for first time. 2700BCE Palestine invaded and occupied by Egyptian infantry and cavalry after Palestinian attacks on trade caravans in Sinai. 2600BCE 2500BCE Harrapan civilization developed in Indian valley. Copper, used for mace heads, found in Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Sumerians make helmets, spearheads and axe blades from bronze. -

Women's Quest for Autonomy in Monastic Life

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga UTC Scholar Student Research, Creative Works, and Honors Theses Publications 12-2019 Feminine agency and masculine authority: women's quest for autonomy in monastic life Kathryn Temple-Council University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Temple-Council, Kathryn, "Feminine agency and masculine authority: women's quest for autonomy in monastic life" (2019). Honors Theses. This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Feminine Agency and Masculine Authority: Women’s Quest for Autonomy in Monastic Life Kathryn Beth Temple-Council Departmental Honors Thesis The University of Tennessee at Chattanooga History Department Examination Date: November 12, 2019 Dr. Kira Robison Assistant Professor of History Thesis Director Michelle White UC Foundation Professor of History Department Examiner Ms. Lindsay Irvin Doyle Adjunct Instructor Department Examiner Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………....….………….1 Historical Background……………………………………...……………………….….……….6 The Sixth Century Church Women’s Monasteries and the Rule for Nuns.………………………………….……………15 The Twelfth Century Church Hildegard of Bingen: Authority Given and Taken.………………………….……………….26 The Thirteenth Century Church Clare of Assisi: A Story Re-written.……………………………………….…………………...37 The Thirteenth through Sixteenth Century Church Enclosure and Discerning Women………………………………………….……...………….49 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………...……….63 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………...…………….64 Introduction From the earliest days of Christianity, women were eager to devote themselves to religious vocation. -

MFB (PDF , 39Kb)

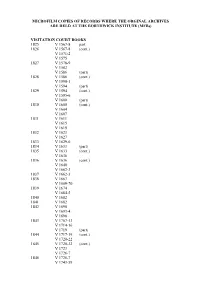

MICROFILM COPIES OF RECORDS WHERE THE ORGINAL ARCHIVES ARE HELD AT THE BORTHWICK INSTITUTE (MFBs) VISITATION COURT BOOKS 1825 V 1567-8 part 1826 V 1567-8 (cont.) V 1571-2 V 1575 1827 V 1578-9 V 1582 V 1586 (part) 1828 V 1586 (cont.) V 1590-1 V 1594 (part) 1829 V 1594 (cont.) V 1595-6 V 1600 (part) 1830 V 1600 (cont.) V 1604 V 1607 1831 V 1611 V 1615 V 1619 1832 V 1623 V 1627 1833 V 1629-0 1834 V 1633 (part) 1835 V 1633 (cont.) V 1636 1836 V 1636 (cont.) V 1640 V 1662-3 1837 V 1662-3 1838 V 1667 V 1669-70 1839 V 1674 V 1684-5 1840 V 1682 1841 V 1682 1842 V 1690 V 1693-4 V 1698 1843 V 1707 -13 V 1714-16 V 1719 (part) 1844 V 1717-19 (cont.) V 1720-22 1845 V 1720-22 (cont.) V 1723 V 1726-7 1846 V 1726-7 V 1743-59 1847 V 1743 (V Book and Papers) V 1748-9 (V Papers) 1848 V 1748-9 (V Book) V 1759-60 (V Book, Papers) 1849 V 1764 (C Book, Ex Book, Papers) V 1770 (part C Book) 1850 V 1770 (cont., CB) V 1777 (C. Book, Papers) V 1781 (Exh Book) 1851 V 1781 (CB and Papers) V 1786 (Papers) 1852 V 1786 (cont., CB) V 1791 (Papers) V 1809 (Call Book and Papers) V 1817 (Call Book) 1853 V 1817, cont. (Call Book) V 1825 (Call Book and Papers) V 1841 (Papers) 1854 V 1841 (Papers cont) V 1849 (Call Book and Papers) V 1853 (Call Book and Papers) CLEVELAND VISITATION COURT BOOKS 1855 C/V/CB. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The constitution and the clergy op Beverley minster in the middle ages McDermid, R. T. W. How to cite: McDermid, R. T. W. (1980) The constitution and the clergy op Beverley minster in the middle ages, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7616/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk II BEVERIEY MINSTER FROM THE SOUTH Three main phases of building are visible: from the East End up to, and including, the main transepts, thirteenth century (commenced c.1230); the nave, fourteenth century (commenced 1308); the West Front, first half of the fifteenth century. The whole was thus complete by 1450. iPBE CONSTIOOTION AED THE CLERGY OP BEVERLEY MINSTER IN THE MIDDLE AGES. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be pubHshed without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

'CLOTHING for the SOUL DIVINE': BURIALSATTHETOMB of ST NINIAN Excavations at Whithorn Priory, 1957-67

'CLOTHING FOR THE SOUL DIVINE': BURIALSATTHETOMB OF ST NINIAN Excavations at Whithorn Priory, 1957-67 Archaeology Report no 3 CHRISTOPHER LOWE with !lpecialist contributions by ( :arol Christiansen, Gordon Cook, Magnar Dalland, Kirsty Dingwall, Julie Franklin, Virginia Glenn, David Henderson, Janet Montgomery, Gundula Miildncr and Richard Oram illustrations by Caroline Norrman, Marion O'Neil, Thomas Small and Craig Williams Edinburgh 2009 Chapter 8 The Medieval Bishops ofWhithorn, their Cathedral and their Tombs RICHARD ORAM H.t THE PRE-REFORMATION BISHOPS OF study by Anne Ashley (1959), which expanded signiticantly WHITHORN OR GALLOWAY upon Donaldson's 1949 paper. After this fruitful decade, however, active research into the medieval episcopate at Whithorn appears to have ceased, with not even the exciting /i. J.I Introduction: historiographical backgro11nd discovery of the series of high-status ecclesiastical burials in i\ld10ugh the diocese ofWhithoru is amongst the more the east end of the cathedral ruins during Ritchie's 1957-67 p<>ur!y documented of Scotland's medieval sees, its bishops excavations serving to stimulate fresh academic interest. l1.1w been the subject of considerably more historical In the 1960s and 1970s, tvvo major projects which 1<'\l':lrch than their counterparts in wealthier, more fOcused on aspects of the medieval Scottish Church 111liut:ntial and better documented dioceses such as Moray, generally cast considerable fi.·esh light on the bishops of 1\!)('rdeen, StAndrews or Glasgow. Much of this research has Whithorn.The first was the second draft of the Fasti Ecdesiac hn·n stimulated by the successive programmes of modern Scoticanae, edited by the late Donald Watt and published in r·x(avation at the ruins of their cathedral at Whithorn, 1969 by the Scottish Records Society (Watt 1969). -

Illegitimacy and English Landed Society C.1285-C.1500 Helen Sarah

Illegitimacy and English Landed Society c.1285-c.1500 Helen Sarah Matthews A thesis presented to Royal Holloway, University of London in Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Helen Sarah Matthews, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________ Date: ________________________ 2 Abstract This study examines the incidence of illegitimacy among members of the landed classes, broadly defined, in late medieval England and the factors which affected the ability of parents to provide for their illegitimate offspring. Illegitimacy has normally been studied from either a legal or a social standpoint. This thesis will combine these approaches in order to provide insight into the social structure of late medieval England. Illegitimacy was a matter which primarily affected the right to inherit property and by implication, the person’s associated status. The period from c.1285, when the statute De Donis Conditionalibus was enacted, to the end of the fifteenth century saw the development of a number of legal devices affecting the ability of landowners to plan the succession to their estates. The enfeoffment to use and the entail allowed landowners the opportunity to settle estates on illegitimate children, or anyone else, without permanently alienating the property from the family line. By the fifteenth century, this freedom of action was becoming restricted by pre-existing entails and a means of breaking entails developed. This study begins with a survey of the legal issues surrounding illegitimacy and the context within which landowners were able to make provision for illegitimate children. -

The Commemoration of Saints at Late Medieval York Minster

The Commemoration of Saints at Late Medieval York Minster Three case studies of the relations between the depictions and accounts of saints’ legends in stained glass windows, liturgical and hagiographic texts Universiteit Utrecht Research Master Thesis Medieval Studies Fenna Visser Student number: 0313890 Supervisors: dr. H.G.E. Rose & dr. T. van Bueren 15 August 2008 2 Contents Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................................... 4 List of Illustrations .................................................................................................................................. 5 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 8 Chapter 1: York Minster: organization and building ............................................................................... 13 Function and organization ................................................................................................................. 13 Architectural history .......................................................................................................................... 19 Chapter 2: Saints’ lives in late medieval England ................................................................................... 22 Hagiography: legends of the saints .................................................................................................... 22 Hagiography