Morning's at Seven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Dean from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Log in / create account Article Discussion Read Edit View history Search James Dean From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page This article is about the actor. For other uses, see James Dean (disambiguation). Contents James Byron Dean (February 8, 1931 – September 30, 1955) Featured content was an American film actor.[1] He is a cultural icon, best James Dean Current events embodied in the title of his most celebrated film, Rebel Without Random article a Cause (1955), in which he starred as troubled Los Angeles Donate to Wikipedia teenager Jim Stark. The other two roles that defined his stardom were as loner Cal Trask in East of Eden (1955), and Interaction as the surly farmer, Jett Rink, in Giant (1956). Dean's enduring Help fame and popularity rests on his performances in only these About Wikipedia three films, all leading roles. His premature death in a car Community portal crash cemented his legendary status.[2] Recent changes Contact Wikipedia Dean was the first actor to receive a posthumous Academy Award nomination for Best Actor and remains the only actor to Toolbox have had two posthumous acting nominations. In 1999, the Print/export American Film Institute ranked Dean the 18th best male movie star on their AFI's 100 Years...100 Stars list.[3] Languages Contents [hide] Dean in 1955 اﻟﻌﺮﺑﻴﺔ Aragonés 1 Early life Born James Byron Dean Bosanski 2 Acting career February 8, 1931 Български Marion, Indiana, U.S. open in browser customize free license pdfcrowd.com Български 2.1 East of Eden Marion, Indiana, U.S. Català 2.2 Rebel Without a Cause Died September 30, 1955 (aged 24) Česky 2.3 Giant Cholame, California, U.S. -

Dr. Strangelove's America

Dr. Strangelove’s America Literature and the Visual Arts in the Atomic Age Lecturer: Priv.-Doz. Dr. Stefan L. Brandt, Guest Professor Room: AR-H 204 Office Hours: Wednesdays 4-6 pm Term: Summer 2011 Course Type: Lecture Series (Vorlesung) Selected Bibliography Non-Fiction A Abrams, Murray H. A Glossary of Literary Terms. Seventh Edition. Fort Worth, Philadelphia, et al: Harcourt Brace College Publ., 1999. Abrams, Nathan, and Julie Hughes, eds. Containing America: Cultural Production and Consumption in the Fifties America. Birmingham, UK: University of Birmingham Press, 2000. Adler, Kathleen, and Marcia Pointon, eds. The Body Imaged. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1993. Alexander, Charles C. Holding the Line: The Eisenhower Era, 1952-1961. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana Univ. Press, 1975. Allen, Donald M., ed. The New American Poetry, 1945-1960. New York: Grove Press, 1960. ——, and Warren Tallman, eds. Poetics of the New American Poetry. New York: Grove Press, 1973. Allen, Richard. Projecting Illusion: Film Spectatorship and the Impression of Reality. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1997. Allsop, Kenneth. The Angry Decade: A Survey of the Cultural Revolt of the Nineteen-Fifties. [1958]. London: Peter Owen Limited, 1964. Ambrose, Stephen E. Eisenhower: The President. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984. “Anatomic Bomb: Starlet Linda Christians brings the new atomic age to Hollywood.” Life 3 Sept. 1945: 53. Anderson, Christopher. Hollywood TV: The Studio System in the Fifties. Austin: Univ. of Texas Press, 1994. Anderson, Jack, and Ronald May. McCarthy: the Man, the Senator, the ‘Ism’. Boston: Beacon Press, 1952. Anderson, Lindsay. “The Last Sequence of On the Waterfront.” Sight and Sound Jan.-Mar. -

Marlon Brando and James Dean

Universidade de Lisboa Faculdade de Letras The Kazan Method: Marlon Brando and James Dean Mariana Araújo Vagos Tese orientada pelo Prof. Doutor José Duarte e co-orientada pela Prof. Doutora Teresa Cid, especialmente elaborada para a obtenção do grau de mestre em Estudos Ingleses e Americanos 2020 2 For my grandfather, who gave me my first book 3 4 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank and acknowledge the strong women in my family who have taught me the meaning of perseverance and are a continuous source of inspiration. I am deeply grateful to my grandfather José, the head of our family, for giving us the tools and encouragement that allowed us to become who we are. He might no longer be among us, but he continues to be our strength and motivation every day. I would like to extend my gratitude to my thesis advisor, Professor Doutor José Duarte, for his patience and understanding throughout the years, until I was finally able to close this chapter of my life. My gratitude also goes to my co-advisor, Professora Doutora Teresa Cid, for her contribute and for accepting be a part of this work. 5 Resumo O objeto principal desta dissertação é o trabalho do realizador Elia Kazan e a sua contribuição para o “Method Acting”. Como tal, o foco será no trabalho desenvolvido pelo realizador com o ator Marlon Brando no filme On the Waterfront (Há Lodo no Cais, 1954), e com o ator James Dean em East of Eden (A Leste do Paraíso, 1955). De modo a explorar o conceito de “Method Acting” como uma abordagem à formação de atores, foi primeiro necessário conhecer o seu predecessor o “System”. -

Film Streams Repertory Calendar August – September 2007 V1.1

Film Streams Repertory Calendar August – September 2007 v1.1 Third Man 1949 We’re late. Typically, our quarterly newsletter will find your mailbox before so many of the films featured within it have come and gone. Starting this October, our Repertory Calendar will arrive loaded with the timeliest of information. In the meantime, there’s still plenty to discover in this introductory issue, including the full run of films for our ADAPTATIONS series this September. For even more details, including up-to-date info about our first- run programming, please visit us at filmstreams.org. —Film Streams Alexander Payne Presents July 27 – August 30, 2007 Seven Samurai 1954 McCabe & Mrs. Miller 1971 Viridiana 1961 The Wild Bunch 1969 Room at the Top 1959 8½ 1963 La Notte 1961 The Last Detail 1973 Modern Times 1936 To Be or Not to Be 1942 We have a lot of reasons for loving Alexander Payne. First, he’s from Omaha, our beloved burg off the coast of the Missouri River. He’s also directed some of the funniest and emotionally honest films of the past decade. And he’s a huge cinephile with a passion for the medium and an encyclopedic knowledge of film history. All of which brings us to our grand opening series. For our initial repertory series, we asked Alexander, an early and wonderful supporter of Film Streams, to select ten of his favorite movies. The result is a series featuring some of the most artistically interesting films ever made—and a unique opportunity to experience the big-screen influences that have shaped a contemporary filmmaker whose work we adore. -

On the Waterfront Fronte Del Porto (1954) East of Eden La Valle Dell'eden

gennaio–marzo 2016 Parte seconda 1954 – 1976 Elia Kazane i suoi attori Marlon Brando James Dean Montgomery Clift … Kazan, Marlon Brando, Julie Harris e James Dean CIRCOLO CIRCOLO LUGANOCINEMA93 CINECLUB DEL DEL CINEMA DEL CINEMA www.luganocinema93.ch MENDRISIOTTO BELLINZONA LOCARNO www.cinemendrisiotto.org www.cicibi.ch www.cclocarno.ch Multisala Teatro Cinema Forum 1+2 Cinema Morettina Cinema Iride Mignon e Ciak Mar 12 gennaio Ven 15 gennaio Mar 19 gennaio Mer 13 gennaio ON THE WATERFRONT 20.30 20.30 20.30 20.45 In collaborazione con il FRONTE DEL PORTO Festival del film Locarno Introduzione di Carlo Chatrian (1954) Direttore artistico del Festival Entrata gratuita Sab 16 gennaio Lun 18 gennaio Mar 26 gennaio Mer 20 gennaio EAST OF EDEN 18.00 18.30 20.30 20.45 LA VALLE DELL’EDEN (1955) Mar 19 gennaio Lun 25 gennaio Mar 2 febbraio BABY DOLL 20.30 18.30 20.30 BABY DOLL, LA BAMBOLA DI CARNE (1956) Sab 23 gennaio Ven 29 gennaio Mar 9 febbraio A FACE IN THE CROWD 18.00 20.30 20.30 UN VOLTO NELLA FOLLA (1957) Mar 26 gennaio Lun 1 febbraio Mar 16 febbraio WILD RIVER 20.30 18.30 20.30 FANGO SULLE STELLE (1960) Sab 30 gennaio Ven 19 febbraio Mar 23 febbraio Mer 27 gennaio SPLENDOR 18.00 20.30 20.30 20.45 IN THE GRASS SPLENDORE NELL’ERBA (1961) Mar 16 febbraio Lun 22 febbraio Mar 1 marzo AMERICA, AMERICA 20.30 18.30 20.30 IL RIBELLE DELL’ANATOLIA (1963) Sab 20 febbraio Mar 8 marzo THE ARRANGEMENT 18.00 20.30 IL COMPROMESSO (1969) Mar 23 febbraio Mar 15 marzo THE VISITORS 20.30 20.30 I VISITATORI (1972) Sab 27 febbraio Ven 26 febbraio Mar 22 marzo THE LAST TYCOON 18.00 20.30 20.30 GLI ULTIMI FUOCHI (1976) Entrata: fr. -

Austintheaterallianceposters.Pdf

Archives > Collections > Fine Arts Library Posters held by the Fine Arts Library's archive of the State and Paramount theatres collection. We are in the process of uploading and linking to images of many of these posters. If you would like to see a particular image online that we have not linked, please contact Ellen Gibbs. Event Creators Event Event Additional ID Event Title Event Venue Event Type Height Width Poster Designer Copyright Date(s) Producer/Promoter Information Michael Palin, Max Wall, Harry H. Corbett, John Le Mystic Cove 1001 Jabberwocky Film 39.5 27 - 2001 Mesurier, Warren Mitchell. Entertainment Director, Terry Gilliam. Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh, Selznick International Leslie Howard, Olivia de Production, re- 50th Anniversary 1002 Gone with the Wind Havilland. Director Victor Film 41 27 1939 released by Metro- Screening Fleming. Author, Margaret Goldwyn-Mayer Inc. Mitchell. Sarah White, Eric Johnson, Erik Markegard, Signature: Neil Ben Keith, Pegi Young, Young, Elizabeth 1003 Greendale James Mazzeo, Elizabeth Film 36 24 Shakey Pictures Keith, Ben Keith, Keith. Bernard Shakey, Pegi Young, and Director. Neil Young, others. Screenplay. No performers listed. Green House Pictures Occupation: 1004 Garrett Scott and Ian Film 36 24 and Subdivision Dreamland Olds, Directors. Productions Tom Hanks, Denzel 1005 Philadelphia Washington. Jonathan Film 39.75 26.75 TriStar Pictures 1993 Demme, Director. Annette Bening, Jeremy 1006 Being Julia Film 40 27 Sony Pictures Classics 2004 Irons The Best Little Burt Reynolds, Dolly Universal-RKO 1007 Whorehouse in Film 40.75 27 1982 Parton Pictures Texas Opens The Lord of the 1008 December Film 40 27 New Line Cinema 2003 Rings 17th Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood. -

Paesaggi Che Cambiano Fango Sulle Stelle (Wild River)

Paesaggi che cambiano rassegna cinematografica secondo ciclo di proiezioni, febbraio-aprile 2017, a cura di Luciano Morbiato mercoledì 22 marzo 2017 Fango sulle stelle (Wild river) di Elia Kazan (durata 105’, USA, 1960) Regia: Elia Kazan; soggetto: dai romanzi Mud on the Stars di William Bradford Huie e Dunbar’s Cove di Borden Deal; sceneggiatura: Paul Osborn; fotografia (De Luxe Color, Cinemascope): Ellsworth Fredericks; scenografia: Lyle Wheeler, Herman A. Blumentahl; arredamento: Walter M. Scott, Joseph Kish; musica: Kenyon Hopkins; aiuto regia: Charles M. Maguire; costumi: Anna Hill Johnstone; consulente per il colore: Leonard Doss; interpreti (e personaggi): Montgomery Clift (Chuck Glover), Lee Remick (Carol), Jo Van Fleet (Ella Garth), Albert Salmi (Hank Bailey), Jay C. Flippen (Hamilton Garth), James Westerfield (Cal Garth), Barbara Loden (Betty Jackson); produzione: 20th Century Fox (produttore E. Kazan); durata: 105’; origine USA; anno 1960. Filmografia di Elia Kazan (Elia Kazanjoglu: Istanbul 1909 – New York 2003): 1941, It’s up to You (t.l. Dipende da te); 1945, Un albero cresce a Brooklyn; 1947, Il mare d’erba; Boomerang, l’arma che uccide; 1948, Barriera invisibile; 1949, Pinky, la negra bianca; 1950, Bandiera gialla; 1952, Un tram chiamato desiderio, Viva Zapata; 1953: Salto mortale; 1954: Fronte del porto; 1955; La valle dell’Eden; 1956: Baby Doll, la bambola di carne; 1957: Un volto nella folla; 1960: Fango sulle stelle; 1961: Splendore nell’erba; 1963: America, America (Il ribelle dell’Anatolia); 1969: Il compromesso; 1972; I visitatori; 1976: Gli ultimi fuochi. Bibliografia essenziale: John H. Lawson, Il film nella battaglia delle idee, Milano, Feltrinelli, 1955; Kazan par Kazan. -

American Revolution Bicentennial Administration(1)

The original documents are located in Box 1, folder “American Revolution Bicentennial Administration (1)” of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 1 of the Philip Buchen Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library AMERICA AT THE MOVIES "The movies," writes Librarian of Congress the guilds and the many individual artists. Daniel J. Boorstin, "were an American in I am grateful to the American Film In vention which, more than any before, focused stitute, an independent non-profit organiza the vision of the world. And motion pictures tion serving the public interest which became the great democratic art, which was established by The National Endowment naturally enough, was the characteristic for the Arts in 1967 to advance the art American art." and preserve the heritage of film in America. It is for this reason that the American I am especially grateful to its Director, Revolution Bicentennial Administration in George A. -

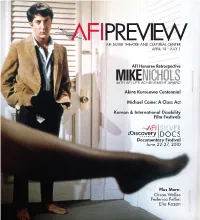

Michael Caine: a Class Act

AFI SILVER THEATRE AND CULTURAL CENTER APRIL 16 - JULY 1 AFI Honoree Retrospective Akira Kurosawa Centennial Michael Caine: A Class Act Korean & International Disability Film Festivals Documentary Festival June 22-27, 2010 JUNE 22-27 2010 Plus More: Orson Welles Federico Fellini Elia Kazan Photo Courtesy of Janus Films THRONE OF BLOOD MICHAEL CAINE: A CLASS ACT MAY 14 - JULY 1 THE IPCRESS FILE GET CARTER FRI, MAY 14, 9:15; SAT, MAY 15, 10:10; THU, MAY 20, 9:15 FRI, MAY 21, 9:30; SAT, MAY 22, 9:45; TUE, MAY 25, 7:00 Looking for a different spin on the spy genre, Harry Saltzman, “You’re a big man, but you’re in co-producer on the early James Bond fi lms (and LOOK BACK bad shape. With me it’s a full- IN ANGER, a huge infl uence on Caine’s generation), cast time job. Now behave yourself.” Caine as the bespectacled Harry Palmer, unimposing and Caine’s existential hard man Jack put-upon by his hardcase superiors. Palmer may be a working Carter is Gangster Number One stiff, but he’s a wised-up one, subtly sarcastic and wary of the in this hugely infl uential, neo-noir old-boy network that’s made a mess of MI6; just the man to classic from talented writer/ root out a traitor in the ranks, as he is called on to do. Director director Mike Hodges. Traveling Sidney J. Furie, famously disdainful of the script (he set at least up from London to Newcastle one copy on fi re) goes visually pyrotechnic with trick shots, after his brother’s mysterious tilted angles, color fi lters and a travelogue’s worth of London death, Carter begins kicking locations. -

Elia Kazan, a FACE in the CROWD, 1957, (115 Min.)

October 28, 2008 (XVII:10) Elia Kazan, A FACE IN THE CROWD, 1957, (115 min.) Produced and Directed by Elia Kazan Written by Budd Schulberg Original Music by Tom Glazer Cinematography by Gayne Rescher and Harry Stradling Sr. Film Editing by Gene Milford Andy Griffith... Larry 'Lonesome' Rhodes Patricia Neal... Marcia Jeffries Anthony Franciosa... Joey DePalma Walter Matthau... Mel Miller Lee Remick... Betty Lou Fleckum R.G. Armstrong... TV Prompter Operator Bennett Cerf... Himself Betty Furness... Herself Virginia Graham... Herself Burl Ives... Himself Sam Levenson... Himself Brownie McGhee... Servant with limp Charles Nelson Reilly... The Nazi Plan (1945), Government Girl (1943), Cinco fueron John Cameron Swayze... Himself escogidos (1943), City Without Men (1943), December 7th Rip Torn... Barry Mills (1943), Five Were Chosen (1942), Weekend for Three (1941), Mike Wallace... Himself Winter Carnival (1939), Little Orphan Annie (1938), Nothing Earl Wilson... Himself Sacred (1937), and A Star Is Born (1937). Walter Winchell... Himself ANDY GRIFFITH (1 June 1926, Mount Airy, North Carolina), ELIA KAZAN (7 September 1909, Constantinople, Ottoman appeared in 70 films an tv series, among them, Play the Game Empire [now Istanbul, Turkey]—28 September 2003, Manhattan, (2008), Waitress (2007), Daddy and Them (2001), Spy Hard New York City, natural causes) won an honorary Oscar in 1999 (1996), "Matlock", “Return to Mayberry”, "The Love Boat", and best director Oscars for On the Waterfront (1954) and Rustlers' Rhapsody (1985), “Six Characters in Search of an Gentlement’s Agreement (1947). He received best director, best Author”, Hearts of the West (1975), "The Doris Day Show", picture and best writing nominations for America, America "Hawaii Five-O", "The Mod Squad", "The New Andy Griffith (1963), and best director nominations for East of Eden (1955) and Show", "Mayberry R.F.D.", "The Andy Griffith Show", "Gomer A Streetcar Named Desire (1951). -

CINEMATECA PORTUGUESA-MUSEU DO CINEMA E a VIDA CONTINUA 14 De Julho De 2020

CINEMATECA PORTUGUESA-MUSEU DO CINEMA E A VIDA CONTINUA 14 de julho de 2020 WILD RIVER / 1960 (Quando o Rio se Enfurece) um filme de Elia Kazan Realização: Elia Kazan / Argumento: Paul Osborn, baseado nos romances Mud on the Stars, de William Bradford Huie, e Dunbar's Cove, de Borden Deal / Direcção de Fotografia: Ellsworth Fredericks / Direcção Artística: Lyle R. Wheeler e Herman Blumenthal / Cenários: Walter M. Scott e Joseph Kish / Música: Kenyon Hopkins / Montagem: William Reynolds / Interpretação: Montgomery Clift (Chuck Glover), Lee Remick (Carol), Jo Van Fleet (Ella Garth), Albert Salmi (Hank Bailey), Jay C. Flippen (Hamilton Garth), James Westerfield (Cal Garth), Barbara Loden (Betty Jackson), Frank Overton (Walter Clark), Malcolm Atterbury (Sy Moore), Robert Earl Jones (Ben), Bruce Dern (Jack Roper), James Steakley (Maynard, o mayor), Hardwick Stuart (xerife Hogue), etc. Produção: 20th Century Fox / Produtor: Elia Kazan / Cópia: 35mm, cor, legendada em espanhol e eletronicamente em português, 110 minutos / Estreia Mundial: Estados Unidos, a 26 de Março de 1960 / Estreia em Portugal: Politeama, a 13 de Abril de 1961. A sessão tem lugar na Esplanada e decorre com intervalo. _____________________________ Entre Wild River e o precedente filme de Kazan, A Face in the Crowd, medeiam quatro anos. Quatro anos em que Kazan, desiludido pelo insucesso comercial dessa obra, voltou as costas ao cinema e se dedicou apenas ao teatro, encenando durante este período uma peça por ano. Desde 1946 e de A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (a estreia de Kazan na longa- metragem) que o cineasta não estava tanto tempo sem filmar. Wild River foi, pois, o projecto escolhido para um regresso à actividade, e não será, consequentemente, um acaso o facto de ser um filme que assinala, na obra de Kazan, uma série de outros "regressos". -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 Arts at Lincoln Center in New York City, the Reviews Of

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into die film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that die photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at die upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.