Investigating Nineteenth-Century Transcriptions Through History of Opera and Music Publishing: Mauro Giuliani's Sources for Tw

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Pietra Del Paragone

LA PIETRA DEL PARAGONE Melodramma giocoso. testi di Luigi Romanelli musiche di Gioachino Rossini Prima esecuzione: 26 settembre 1812, Milano. www.librettidopera.it 1 / 66 Informazioni La pietra del paragone Cara lettrice, caro lettore, il sito internet www.librettidopera.it è dedicato ai libretti d©opera in lingua italiana. Non c©è un intento filologico, troppo complesso per essere trattato con le mie risorse: vi è invece un intento divulgativo, la volontà di far conoscere i vari aspetti di una parte della nostra cultura. Motivazioni per scrivere note di ringraziamento non mancano. Contributi e suggerimenti sono giunti da ogni dove, vien da dire «dagli Appennini alle Ande». Tutto questo aiuto mi ha dato e mi sta dando entusiasmo per continuare a migliorare e ampliare gli orizzonti di quest©impresa. Ringrazio quindi: chi mi ha dato consigli su grafica e impostazione del sito, chi ha svolto le operazioni di aggiornamento sul portale, tutti coloro che mettono a disposizione testi e materiali che riguardano la lirica, chi ha donato tempo, chi mi ha prestato hardware, chi mette a disposizione software di qualità a prezzi più che contenuti. Infine ringrazio la mia famiglia, per il tempo rubatole e dedicato a questa attività. I titoli vengono scelti in base a una serie di criteri: disponibilità del materiale, data della prima rappresentazione, autori di testi e musiche, importanza del testo nella storia della lirica, difficoltà di reperimento. A questo punto viene ampliata la varietà del materiale, e la sua affidabilità, tramite acquisti, ricerche in biblioteca, su internet, donazione di materiali da parte di appassionati. Il materiale raccolto viene analizzato e messo a confronto: viene eseguita una trascrizione in formato elettronico. -

Guillaume Tell Guillaume

1 TEATRO MASSIMO TEATRO GIOACHINO ROSSINI GIOACHINO | GUILLAUME TELL GUILLAUME Gioachino Rossini GUILLAUME TELL Membro di seguici su: STAGIONE teatromassimo.it Piazza Verdi - 90138 Palermo OPERE E BALLETTI ISBN: 978-88-98389-66-7 euro 10,00 STAGIONE OPERE E BALLETTI SOCI FONDATORI PARTNER PRIVATI REGIONE SICILIANA ASSESSORATO AL TURISMO SPORT E SPETTACOLI ALBO DEI DONATORI FONDAZIONE ART BONUS TEATRO MASSIMO TASCA D’ALMERITA Francesco Giambrone Sovrintendente Oscar Pizzo Direttore artistico ANGELO MORETTINO SRL Gabriele Ferro Direttore musicale SAIS AUTOLINEE CONSIGLIO DI INDIRIZZO Leoluca Orlando (sindaco di Palermo) AGOSTINO RANDAZZO Presidente Leonardo Di Franco Vicepresidente DELL’OGLIO Daniele Ficola Francesco Giambrone Sovrintendente FILIPPONE ASSICURAZIONE Enrico Maccarone GIUSEPPE DI PASQUALE Anna Sica ALESSANDRA GIURINTANO DI MARCO COLLEGIO DEI REVISORI Maurizio Graffeo Presidente ISTITUTO CLINICO LOCOROTONDO Marco Piepoli Gianpiero Tulelli TURNI GUILLAUME TELL Opéra en quatre actes (opera in quattro atti) Libretto di Victor Joseph Etienne De Jouy e Hippolyte Louis Florent Bis Musica di Gioachino Rossini Prima rappresentazione Parigi, Théâtre de l’Academie Royale de Musique, 3 agosto 1829 Edizione critica della partitura edita dalla Fondazione Rossini di Pesaro in collaborazione con Casa Ricordi di Milano Data Turno Ora a cura di M. Elizabeth C. Bartlet Sabato 20 gennaio Anteprima Giovani 17.30 Martedì 23 gennaio Prime 19.30 In occasione dei 150 anni dalla morte di Gioachino Rossini Giovedì 25 gennaio B 18.30 Sabato 27 gennaio -

References in Potpourris: 'Artificial Fragments' and Paratexts in Mauro Giuliani's Le Rossiniane Opp. 119–123

References in Potpourris: ‘Artificial Fragments’ and Paratexts in Mauro Giuliani’s Le Rossiniane Opp. 119–123 Francesco Teopini Terzetti Casagrande, Hong Kong The early-nineteenth-century guitar virtuoso Mauro Giuliani (1781– 1829) was a master of the potpourri, a genre of which the main characteristic is the featuring of famous opera themes in the form of musical quotations. Giuliani’s Le Rossiniane comprises six such potpourris for guitar, composed at the time when Rossini was the most famous operatic composer in Europe; they are acknowledged as Giuliani’s chef-d’oeuvre in this genre. Through an investigation of the original manuscripts of Le Rossiniane No. 3, Op. 121, and No. 5, Op. 123, I consider that Giuliani, apparently in order to be fully understood by both performers and audiences, wanted to overtly reference these musical quotations; and that he left various paratextual clues which in turn support the validity of my observations. Utilizing both music and literary theory my analysis investigates and categorizes three types of peritextual elements adopted by Giuliani in order to classify and reference the quoted musical themes in Le Rossiniane for both performers and the public: title, intertitle, and literal note. Further investigation of these works also leads to the hypothesis that each of Giuliani’s musical quotations, called in this paper artificial fragments, can be considered as a further, and essential referential element within the works. At the beginning of the nineteenth century the making of potpourris was the quickest way to compose ‘new’ and successful music. Carl Czerny (1791–1857) stated that the public of that time “experience[d] great delight on finding in a composition some pleasing melody […] which it has previously heard at the Opera […] [and] when […] introduced in a spirited and brilliant manner […] both the composer and the practiced player can ensure great success” (1848 online: 86). -

Download PDF 8.01 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Imagining Scotland in Music: Place, Audience, and Attraction Paul F. Moulton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC IMAGINING SCOTLAND IN MUSIC: PLACE, AUDIENCE, AND ATTRACTION By Paul F. Moulton A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Paul F. Moulton defended on 15 September, 2008. _____________________________ Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Eric C. Walker Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Alison iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In working on this project I have greatly benefitted from the valuable criticisms, suggestions, and encouragement of my dissertation committee. Douglass Seaton has served as an amazing advisor, spending many hours thoroughly reading and editing in a way that has shown his genuine desire to improve my skills as a scholar and to improve the final document. Denise Von Glahn, Michael Bakan, and Eric Walker have also asked pointed questions and made comments that have helped shape my thoughts and writing. Less visible in this document has been the constant support of my wife Alison. She has patiently supported me in my work that has taken us across the country. She has also been my best motivator, encouraging me to finish this work in a timely manner, and has been my devoted editor, whose sound judgement I have come to rely on. -

Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected]

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 4-15-2018 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus Bourne University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Bourne, Thaddaeus, "Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1779. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/1779 Male Zwischenfächer Voices and the Baritenor Conundrum Thaddaeus James Bourne, DMA University of Connecticut, 2018 This study will examine the Zwischenfach colloquially referred to as the baritenor. A large body of published research exists regarding the physiology of breathing, the acoustics of singing, and solutions for specific vocal faults. There is similarly a growing body of research into the system of voice classification and repertoire assignment. This paper shall reexamine this research in light of baritenor voices. After establishing the general parameters of healthy vocal technique through appoggio, the various tenor, baritone, and bass Fächer will be studied to establish norms of vocal criteria such as range, timbre, tessitura, and registration for each Fach. The study of these Fächer includes examinations of the historical singers for whom the repertoire was created and how those roles are cast by opera companies in modern times. The specific examination of baritenors follows the same format by examining current and -

Gioachino Rossini

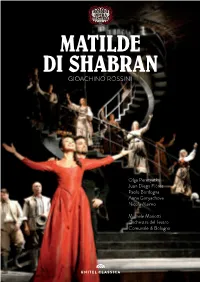

MATILDE DI SHABRAN GIOACHINO ROSSINI Olga Peretyatko Juan Diego Flórez Paolo Bordogna Anna Goryachova Nicola Alaimo Michele Mariotti Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna GIOACHINO ROSSINI MATILDE DI SHABRAN Conductor Michele Mariotti “There truly is a Rossini miracle!” (Deutschlandradio). Acclaiming Orchestra Orchestra del Teatro the mastery of tenorissimo Juan Diego Flórez and the breathtaking Comunale di Bologna young soprano Olga Peretyatko in the lead roles, the press hailed Chorus Coro del Teatro Comunale di Bologna the premiere of Rossini’s Matilde di Shabran at the Rossini Opera Chorus Master Lorenzo Fratini Festival in Pesaro as the “high point of the festival” (the Berlin daily Der Tagesspiegel). Matilde di Shabran Olga Peretyatko Matilde di Shabran was given its world premiere performance in Edoardo Anna Goryachova Rome in 1821. A genuine international hit, it was staged in Vienna, Raimondo Lopez Marco Filippo Romano London, Paris, New York and throughout Italy all before 1830. The Corradino Juan Diego Flórez music of Rossini’s last “opera semiseria” – thus half serious and half Ginardo Simon Orfila comic – contains a succession of beguiling ensemble pieces. The plot Aliprando Nicola Alaimo revolves around the knight Corradino, who has withdrawn to his castle Isidoro Paolo Bordogna and professes to hate his fellow humans. When he meets Matilde di Contessa d’Arco Chiara Chialli Shabran, however, he experiences unknown emotions that have Egoldo Giorgio Misseri nothing to do with hatred... Rodrigo Luca Visani Leading the Orchestra del Teatro Comunale di Bologna, conductor Staged by Mario Martone Michele Mariotti commands an ideal ensemble of singers: while Juan Diego Flórez, “perhaps the best Rossini tenor of our time” Video Director Tiziano Mancini (Deutschlandradio), sings the role of Corradino, that of Matilde is “gorgeously sung by Olga Peretyatko” (The New York Times). -

![[STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , Von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2533/stendhal-joachim-rossini-von-maria-ottinguer-leipzig-1852-472533.webp)

[STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , Von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852

REVUE DES DEUX MONDES , 15th May 1854, pp. 731-757. Vie de Rossini , par M. BEYLE [STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852. SECONDE PÉRIODE ITALIENNE. — D’OTELLO A SEMIRAMIDE. IV. — CENERENTOLA ET CENDRILLON. — UN PAMPHLET DE WEBER. — LA GAZZA LADRA. — MOSÈ [MOSÈ IN EGITTO]. On sait que Rossini avait exigé cinq cents ducats pour prix de la partition d’Otello (1). Quel ne fut point l’étonnement du maestro lorsque le lendemain de la première représentation de son ouvrage il reçut du secrétaire de Barbaja [Barbaia] une lettre qui l’avisait qu’on venait de mettre à sa disposition le double de cette somme! Rossini courut aussitôt chez la Colbrand [Colbran], qui, pour première preuve de son amour, lui demanda ce jour-là de quitter Naples à l’instant même. — Barbaja [Barbaia] nous observe, ajouta-t-elle, et commence à s’apercevoir que vous m’êtes moins indifférent que je ne voudrais le lui faire croire ; les mauvaises langues chuchotent : il est donc grand temps de détourner les soupçons et de nous séparer. Rossini prit la chose en philosophe, et se rappelant à cette occasion que le directeur du théâtre Valle le tourmentait pour avoir un opéra, il partit pour Rome, où d’ailleurs il ne fit cette fois qu’une rapide apparition. Composer la Cenerentola fut pour lui l’affaire de dix-huit jours, et le public romain, qui d’abord avait montré de l’hésitation à l’endroit de la musique du Barbier [Il Barbiere di Siviglia ], goûta sans réserve, dès la première épreuve, cet opéra, d’une gaieté plus vivante, plus // 732 // ronde, plus communicative, mais aussi trop dépourvue de cet idéal que Cimarosa mêle à ses plus franches bouffonneries. -

Parte Il Celeberrimo ‘A Solo’ «Le Perfide Renaud Me Fuit»

La Scena e l’Ombra 13 Collana diretta da Paola Cosentino Comitato scientifico: Alberto Beniscelli Bianca Concolino Silvia Contarini Giuseppe Crimi Teresa Megale Lisa Sampson Elisabetta Selmi Stefano Verdino DOMENICO CHIODO ARMIDA DA TASSO A ROSSINI VECCHIARELLI EDITORE Pubblicato con il contributo dell’Università di Torino Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici © Vecchiarelli Editore S.r.l. – 2018 Piazza dell’Olmo, 27 00066 Manziana (Roma) Tel. e fax 06.99674591 [email protected] www.vecchiarellieditore.com ISBN 978-88-8247-419-5 Indice Armida nella Gerusalemme liberata 7 Le prime riscritture secentesche 25 La seconda metà del secolo 59 Il paradosso haendeliano e le Armide rococò 91 Ritorno a Parigi (passando per Vienna) 111 Ritorno a Napoli 123 La magia è il teatro 135 Bibliografia 145 Indice dei nomi 151 ARMIDA NELLA GERUSALEMME LIBERATA Per decenni, ma forse ancora oggi, tra i libri di testo in uso nella scuola secondaria per l’insegnamento letterario ha fatto la parte del leone il manuale intitolato Il materiale e l’immaginario: se lo si consulta alle pa- gine dedicate alla Gerusalemme liberata si può leggere che del poema «l’argomento è la conquista di Gerusalemme da parte dei crociati nel 1099» e che «Tasso scelse un argomento con caratteri non eruditi ma di attualità e a forte carica ideologica. Lo scontro fra l’Occidente cri- stiano e l’Islam - il tema della crociata - si rinnovava infatti per la mi- naccia dell’espansionismo turco in Europa e nel Mediterraneo». Tale immagine del poema consegnata alle attuali generazioni può conser- varsi soltanto a patto, come di fatto è, che non ne sia proprio prevista la lettura e viene da chiedersi che cosa avrebbero pensato di tali af- fermazioni gli europei dei secoli XVII e XVIII, ovvero dei secoli in cui la Liberata era lettura immancabile per qualunque europeo mediamen- te colto. -

Acc Ross LOCANDINA 2014

ACCADEMIA ROSSINIANA Seminario permanente di studio sui problemi della interpretazione rossiniana diretto da Alberto Zedda 2014 3~18 luglio Teatro Sperimentale PROGRAMMA Giovedì 3 luglio Sabato 12 luglio 11.00 - 13.30 Inaugurazione dell’Accademia e 10.30 - 13.30 Master Class Juan Diego Flórez presentazione dei corsi 15.30 - 19.30 L’avventura del trucco Luca Oblach Gianfranco Mariotti, Alberto Zedda 15.30 - 19.00 Corso di interpretazione vocale Domenica 13 luglio Riposo condotto da Alberto Zedda Coordinamento musicale Anna Bigliardi Lunedì 14 luglio 10.30 - 13.00 Corso di interpretazione vocale Venerdì 4 luglio 16.00 - 17.30 Cantare Rossini: teoria e pratica 10.30 - 13.30 Corso di interpretazione vocale 18.30 - 20.00 Incontro con gli artisti di Armida 16.00 - 18.00 Dalla funzione dei muscoli del tronco al canto Frank Musarra Martedì 15 luglio 10.30 - 13.30 Corso di interpretazione vocale Sabato 5 luglio 15.00 - 16.30 Il mio lavoro come regista d’opera 10.30 - 13.30 Master Class Mario Martone 15.30 - 18.30 La consapevolezza dei risuonatori 18.00 - 20.00 Incontro con gli artisti di al servizio del timbro vocale: fisiologia Aureliano in Palmira e prevenzione Franco Fussi Mercoledì 16 luglio Domenica 6 luglio Riposo 10.30 - 12.30 Corso di interpretazione vocale 12.30 - 13.30 Discussione su temi e contenuti Lunedì 7 luglio dell’Accademia 2014 10.30 - 13.30 Corso di interpretazione vocale 15.30 - 19.30 Momenti di interpretazione 16.00 - 18.00 Il suono e l’improvvisazione e improvvisazione Elisabetta Courir Marco Mencoboni Giovedì 17 luglio Martedì -

Signumclassics

170booklet 6/8/09 15:21 Page 1 ALSO AVAILABLE on signumclassics Spanish Heroines Silvia Tro Santafé Orquesta Sinfónica de Navarra Julian Reynolds conductor SIGCD152 Since her American debut in the early nineties, Silvia Tro Santafé has become one of the most sought after coloratura mezzos of her generation. On this disc we hear the proof of her operatic talents, performing some of the greatest and most passionate arias of any operatic mezzo soprano. Available through most record stores and at www.signumrecords.com For more information call +44 (0) 20 8997 4000 170booklet 6/8/09 15:21 Page 3 Rossini Mezzo Rossini Mezzo gratitude, the composer wrote starring roles for her in five of his early operas, all but one of them If it were not for the operas of Gioachino Rossini, comedies. The first was the wickedly funny Cavatina (Isabella e Coro, L’Italiana in Algeri) the repertory for the mezzo soprano would be far L’equivoco stravagante premiered in Bologna in 1. Cruda sorte! Amor tiranno! [4.26] less interesting. Opera is often thought of as 1811. Its libretto really reverses the definition of following generic lines and the basic opera plot opera quotes above. In this opera, the tenor stops Coro, Recitativo e Rondò (Isabella, L’Italiana in Algeri) has been described as “the tenor wants to marry the baritone from marrying the mezzo and does it 2. Pronti abbiamo e ferri e mani (Coro), Amici, in ogni evento ... (Isabella) [2.45] the soprano and bass tries to stop them”. by telling him that she is a castrato singer in drag. -

La Colección De Música Del Infante Don Francisco De Paula Antonio De Borbón

COLECCIONES SINGULARES DE LA BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL 10 La colección de música del infante don Francisco de Paula Antonio de Borbón COLECCIONES SINGULARES DE LA BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL DE ESPAÑA, 10 La colección de música del infante don Francisco de Paula Antonio de Borbón en la Biblioteca Nacional de España Elaborado por Isabel Lozano Martínez José María Soto de Lanuza Madrid, 2012 Director del Departamento de Música y Audiovisuales José Carlos Gosálvez Lara Jefa del Servicio de Partituras Carmen Velázquez Domínguez Elaborado por Isabel Lozano Martínez José María Soto de Lanuza Servicio de Partituras Ilustración p. 4: Ángel María Cortellini y Hernández, El infante Francisco de Paula, 1855. Madrid, Museo del Romanticismo, CE0523 NIPO: 552-10-018-X © Biblioteca Nacional de España. Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte © De los textos introductorios: sus autores Catálogo general de publicaciones ofi ciales de la Administración General del Estado: http://publicacionesofi ciales.boe.es CATALOGACIÓN EN PUBLICACIÓN DE LA BIBLIOTECA NACIONAL DE ESPAÑA Biblioteca Nacional de España La colección de música del infante don Francisco de Paula Antonio de Borbón en la Biblioteca Nacional de España / elaborado por Isabel Lozano Martínez, José María Soto de Lanuza. – Madrid : Biblioteca Nacional de España, 2012 1 recurso en línea : PDF. — (Colecciones singulares de la Biblioteca Nacional ; 10) Bibliografía: p. 273-274. Índices Incluye transcripción y reproducción facsímil del inventario manuscrito M/1008 NIPO 552-10-018-X 1. Borbón, Francisco de Paula de, Infante de España–Biblioteca–Catálogos. 2. Partituras–Biblioteca Nacional de España– Catálogos. 3. Música–Manuscritos–Bibliografías. I. Lozano, Isabel (1960-). II. Soto de Lanuza, José María (1954- ). -

Gioachino Rossini (1792–1868)

4 CDs 4 Christian Benda Christian Prague Sinfonia Orchestra Sinfonia Prague COMPLETE OVERTURES COMPLETE ROSSINI GIOACHINO COMPLETE OVERTURES ROSSINI GIOACHINO 4 CDs 4 GIOACHINO ROSSINI (1792–1868) COMPLETE OVERTURES Prague Sinfonia Orchestra Christian Benda Rossini’s musical wit and zest for comic characterisation have enriched the operatic repertoire immeasurably, and his overtures distil these qualities into works of colourful orchestration, bravura and charm. From his most popular, such as La scala di seta (The Silken Ladder) and La gazza ladra (The Thieving Magpie), to the rarity Matilde of Shabran, the full force of Rossini’s dramatic power is revealed in these masterpieces of invention. Each of the four discs in this set has received outstanding international acclaim, with Volume 2 described as “an unalloyed winner” by ClassicsToday, and the Prague Sinfonia Orchestra’s playing described as “stunning” by American Record Guide (Volume 3). COMPLETE OVERTURES • 1 (8.570933) La gazza ladra • Semiramide • Elisabetta, Regina d’Inghilterra (Il barbiere di Siviglia) • Otello • Le siège de Corinthe • Sinfonia in D ‘al Conventello’ • Ermione COMPLETE OVERTURES • 2 (8.570934) Guillaume Tell • Eduardo e Cristina • L’inganno felice • La scala di seta • Demetrio e Polibio • Il Signor Bruschino • Sinfonia di Bologna • Sigismondo COMPLETE OVERTURES • 3 (8.570935) Maometto II (1822 Venice version) • L’Italiana in Algeri • La Cenerentola • Grand’overtura ‘obbligata a contrabbasso’ • Matilde di Shabran, ossia Bellezza, e cuor di ferro • La cambiale di matrimonio • Tancredi CD 4 COMPLETE OVERTURES • 4 (8.572735) Il barbiere di Siviglia • Il Turco in Italia • Sinfonia in E flat major • Ricciardo e Zoraide • Torvaldo e Dorliska • Armida • Le Comte Ory • Bianca e Falliero 8.504048 Booklet Notes in English • Made in Germany ℗ 2013, 2014, 2015 © 2017 Naxos Rights US, Inc.