England's Economic Heartland Rail Study Phase 1 15 MB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Counties Connected a Rail Prospectus for East Anglia Our Counties Connected a Rail Prospectus for East Anglia

Our Counties Connected A rail prospectus for East Anglia Our Counties Connected A rail prospectus for East Anglia Contents Foreword 3 Looking Ahead 5 Priorities in Detail • Great Eastern Main Line 6 • West Anglia Main Line 6 • Great Northern Route 7 • Essex Thameside 8 • Branch Lines 8 • Freight 9 A five county alliance • Norfolk 10 • Suffolk 11 • Essex 11 • Cambridgeshire 12 • Hertfordshire 13 • Connecting East Anglia 14 Our counties connected 15 Foreword Our vision is to release the industry, entrepreneurship and talent investment in rail connectivity and the introduction of the Essex of our region through a modern, customer-focused and efficient Thameside service has transformed ‘the misery line’ into the most railway system. reliable in the country, where passenger numbers have increased by 26% between 2005 and 2011. With focussed infrastructure We have the skills and enterprise to be an Eastern Economic and rolling stock investment to develop a high-quality service, Powerhouse. Our growing economy is built on the successes of East Anglia can deliver so much more. innovative and dynamic businesses, education institutions that are world-leading and internationally connected airports and We want to create a rail network that sets the standard for container ports. what others can achieve elsewhere. We want to attract new businesses, draw in millions of visitors and make the case for The railways are integral to our region’s economy - carrying more investment. To do this we need a modern, customer- almost 160 million passengers during 2012-2013, an increase focused and efficient railway system. This prospectus sets out of 4% on the previous year. -

Railfuture Response to Consultations on the Proposed East Coast Main Line Timetable May 2022

RAILFUTURE RESPONSE TO CONSULTATIONS ON THE PROPOSED EAST COAST MAIN LINE TIMETABLE MAY 2022 From: Railfuture Passenger Group & Branches: East Anglia, East Midlands, Lincolnshire, London & South East, North East, North West, Yorkshire & Scotland Submitted to: CrossCountry, Great Northern/Thameslink, LNER, Northern, TransPennine Express Copied to: East Midlands Railway, First East Coast Trains, Grand Central, Hull Trains, Network Rail & ScotRail Index Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Background ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 Executive Summary....................................................................................................................................... 2 Strategic Interventions .................................................................................................................................. 3 LNER ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 Responses to LNER Questionnaire ............................................................................................ 6 TransPennine Express .................................................................................................................................. 9 CrossCountry ............................................................................................................................................... -

Rf LTW Chiltern Response

campaigning by the Railway Development Society Limited Development of Train Services for Chiltern Routes Response from Railfuture 1. Introduction Railfuture is pleased to respond to the London TravelWatch document regarding the Development of Train Services for Chiltern Routes. Our comments will be brief and to the point. Railfuture is the campaigning name of the Railway Development Society Limited, a (not for profit) Limited Company organised in England as twelve regional branches plus two national branches in Scotland and Wales. This coordinated response has been compiled by Railfuture London & South East, and has been agreed with Railfuture Thames Valley for those sections of line in their area (Amersham to Aylesbury and West Ruislip to Bicester North). 2. General Comments Railfuture welcomes the initiative from LTW to suggest ways of raising standards of service on Chiltern Railways services in London and South East. We note the work that has gone into gathering the detail on network capacity and existing services. Chiltern is unique for a number of reasons: its close working relationship and shared infrastructure with London Underground (LU) on the Aylesbury Line; the close proximity of other LU and London Bus services to many Chiltern ‘metro’ stations on the High Wycombe line; the close mix of short and medium distance commuter traffic and the poor interchange facilities at Marylebone. It is equally unique for the impressive increase in patronage generated by reliable modern rolling stock and infrastructure; the benefits of a long-term franchise agreement and an imaginative customer oriented professional management team. It is also inhibited by many of the factors that make it unique! These range from the poor interchange facilities at Marylebone, to a lack of infrastructure between Wembley and West Ruislip. -

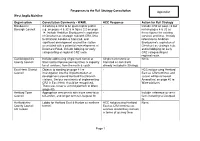

Responses to the Rail Strategy Consultation Page 1 West Anglia

Responses to the Rail Strategy Consultation Appendix1 West Anglia Mainline Organisation Consultation Comments - WAML HCC Response Action for Rail Strategy Broxbourne 4-tracking & CR2 to be given higher profile - Include CR2 on page 14 but Borough Council e.g. on pages 4 & 32 & in figure 2.2 on page not on pages 4 & 32 as 14. Include Ambition Broxbourne's aspiration these figures list existing of Cheshunt as strategic hub with CR2, links services and lines. Include to Stratford, London & Stansted, and reference to Ambition significant development around the station Broxbourne's aspiration of associated with a potential redevelopment of Cheshunt as strategic hub, Delamare Road. Include lobbying for early and of lobbying for early safeguarding of regional CR2 route. CR2 safeguarding of regional route. Cambridgeshire Include addressing single track tunnel at Single track tunnel at None. County Council Stansted to improve journey times & capacity Stansted as constraint for all services, from the north & south. already included in Strategy. East Herts District Objects to wording on page 41 re - HCC not pursuing Hertford Council investigation into the implementation of East as CR2 terminus and development around Hertford East branch so text will be removed. stations. Serious constraints of implementing Amend text on page 40 re CR2 in East Herts should be recognised. Ware platform. There was never a second platform at Ware (page 40). Hertford Town Appropriate service mix with more semi-fasts - Include reference to semi- Council to London, and longer term to Liverpool St. fasts including to Liverpool St. Hertfordshire Lobby for Hertford East & Harlow as northern HCC not pursuing Hertford None. -

Solent to the Midlands Multimodal Freight Strategy – Phase 1

OFFICIAL SOLENT TO THE MIDLANDS MULTIMODAL FREIGHT STRATEGY – PHASE 1 JUNE 2021 OFFICIAL TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 2. STRATEGIC AND POLICY CONTEXT ................................................................................................................................................... 11 3. THE IMPORTANCE OF THE SOLENT TO THE MIDLANDS ROUTE ........................................................................................................ 28 4. THE ROAD ROUTE ............................................................................................................................................................................. 35 5. THE RAIL ROUTE ............................................................................................................................................................................... 40 6. KEY SECTORS .................................................................................................................................................................................... 50 7. FREIGHT BETWEEN THE SOLENT AND THE MIDLANDS .................................................................................................................... -

Bibliography19802017v2.Pdf

A LIST OF PUBLICATIONS ON THE HISTORY OF WARWICKSHIRE, PUBLISHED 1980–2017 An amalgamation of annual bibliographies compiled by R.J. Chamberlaine-Brothers and published in Warwickshire History since 1980, with additions from readers. Please send details of any corrections or omissions to [email protected] The earlier material in this list was compiled from the holdings of the Warwickshire County Record Office (WCRO). Warwickshire Library and Information Service (WLIS) have supplied us with information about additions to their Local Studies material from 2013. We are very grateful to WLIS for their help, especially Ms. L. Essex and her colleagues. Please visit the WLIS local studies web pages for more detailed information about the variety of sources held: www.warwickshire.gov.uk/localstudies A separate page at the end of this list gives the history of the Library collection, parts of which are over 100 years old. Copies of most of these published works are available at WCRO or through the WLIS. The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust also holds a substantial local history library searchable at http://collections.shakespeare.org.uk/. The unpublished typescripts listed below are available at WCRO. A ABBOTT, Dorothea: Librarian in the Land Army. Privately published by the author, 1984. 70pp. Illus. ABBOTT, John: Exploring Stratford-upon-Avon: Historical Strolls Around the Town. Sigma Leisure, 1997. ACKROYD, Michael J.M.: A Guide and History of the Church of Saint Editha, Amington. Privately published by the author, 2007. 91pp. Illus. ADAMS, A.F.: see RYLATT, M., and A.F. Adams: A Harvest of History. The Life and Work of J.B. -

Consultation Technical Report

Making Meaningful Connections Consultation Technical Report East West Rail Consultation: 31 March – 9 June 2021 This document contains the full Consultation Technical Report, without the Appendices. To access the Appendices, please visit www.eastwestrail.co.uk 01. Introduction 18 - 26 07. Project Section B: Bletchley and the Marston Vale Line 100 - 229 1.1. Chapter Summary 18 7.1. Chapter Summary 101 1.2. East West Rail 19 7.2. Introduction 104 1.3. The Project 19 7.3. Service Concepts 109 1.4. Consultation 23 7.4. Bletchley Station 141 1.5. Technical Report 26 7.5. Fenny Stratford Additional Track 144 02. The Case for East West Rail 27 - 31 7.6. Level Crossings on the Marston Vale Line 146 2.1. Chapter Summary 27 7.7. Marston Vale Line Infrastructure Upgrade 228 2.2. The overall case for East West Rail 28 08. Project Section C: Bedford 230 - 299 2.3. Benefits of railways over road improvements 31 8.1. Chapter Summary 230 03. Project Objectives 32 - 42 8.2. Introduction 234 3.1. Chapter Summary 32 8.3. Bedford St Johns 238 3.2. Introduction 33 8.4. Bedford Station 250 3.3. Safety 34 8.5. North Bedford 268 3.4. Environment 34 8.6. Conclusion 297 3.5. EWR Services 34 09. Project Section D: Clapham Green to The Eversdens 300 - 371 3.6. Connectivity 36 9.1. Chapter Summary 301 3.7. Customer Experience and Stations 37 9.2. Introduction 303 3.8. Powering EWR Services 38 9.3. Option Development 306 3.9. -

Annex G – Forming & Delivering a Strategy

Swindon and Wiltshire Rail Study 09/05/2019 Reference number 107523 ANNEX G – FORMING & DELIVERING A STRATEGY SWINDON AND WILTSHIRE RAIL STUDY ANNEX G – FORMING & DELIVERING A STRATEGY IDENTIFICATION TABLE Client/Project owner Swindon and Wiltshire Local Enterprise Partnership Project Swindon and Wiltshire Rail Study Study Annex G – Forming & Delivering a Strategy Type of document Report Date 09/05/2019 File name Framework N/A Reference number 107523 Number of pages 33 APPROVAL Version Name Position Date Modifications Author J Jackson Associate 12/03/2019 Checked A Sykes Associate 13/03/2019 1 by Approved D Bishop Director 15/03/2019 by Author J Jackson Associate 09/05/2019 Checked A Sykes Associate 09/05/2019 2 by Approved A Sykes Associate 09/05/2019 by TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION 6 2. IDENTIFYING THE COMPONENTS OF THE STRATEGY 7 3. NETWORK-WIDE INITIATIVES 8 4. GREAT WESTERN MAINLINE 11 RECOMMENDATIONS 11 PHASE 0: 1 TPH WESTBURY – SWINDON 12 PHASE 1: 1 TPH SOUTHAMPTON CENTRAL – SWINDON 13 PHASE 2 & 2A: GREAT WESTERN CONNECT 14 PHASE 3: EXTENSION OF GREAT WESTERN CONNECT 16 DELIVERY OF GREAT WESTERN CONNECT 16 THE SOUTH COTSWOLDS LINE 17 5. BERKS & HANTS ROUTE 18 EXTENSION OF LONDON – BEDWYN SERVICES 18 DEVIZES PARKWAY 19 EXTENSION OF LONDON – WESTBURY SERVICES TO BRISTOL (PEAK ONLY) 19 ENHANCEMENT OF PADDINGTON – EXETER SERVICES TO HOURLY 19 DELIVERING AND ENHANCED BERKS & HANTS SERVICE 19 6. WEST OF ENGLAND LINE 21 SALISBURY – LONDON JOURNEY TIME REDUCTIONS 21 PORTON STATION 22 WILTON STATION 23 ANDOVER – LUDGERSHALL LINE 23 7. TRANS WILTS CORRIDOR 24 ASHTON PARK STATION 25 THE IMPACT OF METRO WEST 25 8. -

Harvington Conservation Area

Harvington Conservation Area Harvington The Harvington Area Appraisal and Management Proposals were adopted by Wychavon District Council as a document for planning purposes. Minute 53 of the Executive Board meeting of 25 November 2015 refers. Wychavon District Council Planning Services Civic Centre Queen Elizabeth Drive Pershore Worcestershire WR10 1PT Tel. 01386 565000 www.wychavon.gov.uk 1 Harvington 1 Part 1 APPRAISAL 1 INTRODUCTION 2 Purpose of a Conservation Area Appraisal Planning Policy Framework 2 SUMMARY OF SPECIAL INTEREST 3 3 ASSESSING SPECIAL INTEREST 4 Location & Landscape Setting Historical Development & Archaeology Plan Form Spaces Key Views & Vistas 4 CHARACTER ANALYSIS 14 General Buildings Materials Local Details Boundaries Natural Environment Negative Features & Neutral Areas Threats 5 ISSUES 28 Appraisal Map Part 2 MANAGEMENT PROPOSALS 31 1 INTRODUCTION 2 MANAGEMENT PROPOSALS 3 DESIGN CODES 4 ARTICLE 4(2) DIRECTIONS APPENDIX 01 Statement of Community Involvement APPENDIX 02 Sources & Further Information 1 Harvington 2 Part 1 …………………………………… Planning Policy Framework CONSERVATION AREA 1.4 This appraisal should be read in APPRAISAL conjunction with the Development Plan, which comprises the saved policies of the 1 INTRODUCTION Wychavon District Local Plan (June 2006) and national planning policy as set out in the National Planning Policy Framework Purpose of a Conservation Area (March 2012) specifically Wychavon Appraisal District Local Plan Policy Env12 which is 1.1 intended to ensure that development A conservation area is an “area of special preserves or enhances the character or architectural or historic interest, the appearance of conservation areas. character or appearance of which it is desirable to preserve or enhance” National Planning Policy Framework 126 – (Planning (Listed Buildings and 141 sets out the Governments planning Conservation Areas) Act 1990, Section policy on conserving and enhancing the 69). -

Watford Character of Area Study

Character Area 18 Period Generally 1930s. Includes 1900s – 1950s. Heights Predominantly two storeys. Some bungalows. Urban grain Intermediate form. Block size / structure Regular pattern of blocks varying in size (450m x 80m). Generally larger block sub-division than Victorian/Edwardian development. Plot sizes Typically 8m x 40m. Gaps between buildings of 4m- 5m. Streetscene Suburban streetscene. Wide carriageways (6-7m for total), with pavements of 2.5-3.5m widths – some of which feature street trees. Limited street furniture. Building lines Generally consistent building lines behind front gardens. Front boundaries Marked by hedges of varying heights, brick walls or timber fences. Many original hedges / walls are now open frontages to allow car access. Roof forms Generally hipped tile roofs, with brick chimneys. Windows Originally metal or timber framed windows. These have generally been replaced since with various types of uPVC windows. Projecting two storey bay windows are common. Materials Materials include variety of brick types, render and mock-Tudor style timbering. Tile roofs. Car parking Large proportion of houses have garages as later additions to the side. Majority of parking is accommodated in front drives. Some on-street parking. Landscaping Front gardens typically 6m deep. Rear gardens typically 15m-25m deep. Hedges are relatively common in rear gardens, but less so in front gardens. Street tree planting along some pavements. Limited green space outside of gardens and formal parkland/playing fields/allotments. No grass verges between carriageways and pavements 103 Character Area 18A 104 Area 18A Summary This residential character area is located on the eastern side of the Borough, at the border with Hertsmere. -

The Elizabeth Line

COMPLETING ELIZABETH LINE THE ELIZABETH LINE Trial Running Update TRIAL RUNNING Plumstead Sidings PROJECT UPDATE WHAT IS TRIAL RUNNING? Delivery of the Elizabeth line is now in its Throughout the Trial Running programme Crossrail will Trial Running marks the point at which the Railways and complex final stages. Crossrail and Transport steadily increase the numbers of trains running in the tunnels. Other Guided Transport Systems (Safety) Regulations 2006 This will then be further increased and will allow the railway (ROGS) apply for the first time in the Central Operating for London (TfL) are working to ensure the and the supporting systems to be operated as close as Section. Crossrail transitions from following the construction earliest possible opening for the Elizabeth line. possible to an operational timetable. regulations to following Rail regulations. The project is nearing the next important milestone and There is important work to be done but we will take the time Following a readiness review, we will sign over control of the expects to commence extensive commissioning of the railway needed to get it right. Our top priority is a safe railway which central operating section to TfL as infrastructure manager as in spring 2021. This is a crucial moment in the project with the London and the UK can rely on. we transition to ROGS and operate under the Railway Rule railway on track to open in the first half of 2022. Book. From that moment forward, TfL’s service and The progress we have seen over recent months highlights the infrastructure managers will be accountable for the safety, The next phase, Trial Running, involves integrated trials of clear path we have towards completing the Elizabeth line and operation and maintenance of the railway, and the Trial the railway to demonstrate that the Elizabeth line is safe and commencing passenger services in the first half of 2022. -

Brunel's Dream

Global Foresights | Global Trends and Hitachi’s Involvement Brunel’s Dream Kenji Kato Industrial Policy Division, Achieving Comfortable Mobility Government and External Relations Group, Hitachi, Ltd. The design of Paddington Station’s glass roof was infl u- Renowned Engineer Isambard enced by the Crystal Palace building erected as the venue for Kingdom Brunel London’s fi rst Great Exhibition held in 1851. Brunel was also involved in the planning for Crystal Palace, serving on the The resigned sigh that passed my lips on arriving at Heathrow building committee of the Great Exhibition, and acclaimed Airport was prompted by the long queues at immigration. the resulting structure of glass and iron. Being the gateway to London, a city known as a melting pot Rather than pursuing effi ciency in isolation, Brunel’s of races, the arrivals processing area was jammed with travel- approach to constructing the Great Western Railway was to ers from all corners of the world; from Europe of course, but make the railway lines as fl at as possible so that passengers also from the Middle East, Africa, Asia, and North and South could enjoy a pleasant journey while taking in Britain’s won- America. What is normally a one-hour wait can stretch to derful rural scenery. He employed a variety of techniques to two or more hours if you are unfortunate enough to catch a overcome the constraints of the terrain, constructing bridges, busy time of overlapping fl ight arrivals. While this only adds cuttings, and tunnels to achieve this purpose. to the weariness of a long journey, the prospect of comfort Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway, a famous awaits you on the other side.