The Information Structure of the Book of Esther in the Septuagint by Ken

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Week #: 33 Text: Esther 1-10 Title: Feast of Purim Songs

Week #: 33 Text: Esther 1-10 Title: Feast of Purim Songs: Videos: Purim Song – The Maccabeats Audio Reading: Book of Esther Feast of Purim Purim is an annual celebration of the defeat of an Iranian mad man’s plan to exterminate the Jewish people. Purim is celebrated annually during the month of Adar (the second month of Adar) on the 14th day. In years where there are two months of Adar, Purim is celebrated in the second month because it always needs to fall 30 days before Passover. It is called Purim because the word means “lots” – referencing when Haman threw lots to decide which day he would slay the Jews. The fourteenth was chosen for this celebration because it is the day that the Jews battled for their lives and won. The fifteenth is celebrated as Purim also because the book of Esther says that in Shushan (a walled city), deliverance from the scheduled massacre was not completed until the next day. So the fifteenth is referred to as Shushan Purim. Traditions for the Feast of Purim: It is customary to read the book of Esther – called the Megillah Esther – or the scroll of Esther. It means the revelation of that which is hidden While reading it is tradition to boo, hiss, stamp feet and rattle noise makers whenever Haman’s name is mentioned for the purpose of “blotting out the name of Haman”. When the names of Mordechai or Esther are spoken, hoots and hollers, cheering, applause, etc., are given as they are the heroes of the story. -

Esther Through the Centuries (Blackwell Bible Commentaries)

Esther Through the Centuries Jo Carruthers Esther Through the Centuries Blackwell Bible Commentaries Series Editors: John Sawyer, Christopher Rowland, Judith Kovacs, David M. Gunn John Th rough the Centuries Ecclesiastes Th rough the Centuries Mark Edwards Eric S. Christianson Revelation Th rough the Centuries Esther Th rough the Centuries Judith Kovacs & Christopher Rowland Jo Carruthers Judges Th rough the Centuries Psalms Th rough the Centuries: David M. Gunn Volume One Exodus Th rough the Centuries Susan Gillingham Scott M. Langston Galatians Th rough the Centuries John Riches Forthcoming: Leviticus Th rough the Centuries Th e Minor Prophets Th rough the Mark Elliott Centuries 1 & 2 Samuel Th rough the Centuries Jin Han & Richard Coggins David M. Gunn Mark Th rough the Centuries 1 & 2 Kings Th rough the Centuries Christine Joynes Martin O’Kane Luke Th rough the Centuries Psalms Th rough the Centuries: Larry Kreitzer Volume Two Th e Acts of the Apostles Th rough the Susan Gillingham Centuries Song of Songs Th rough the Centuries Heidi J. Hornik & Mikael C. Parsons Francis Landy & Fiona Black Romans Th rough the Centuries Isaiah Th rough the Centuries Paul Fiddes John F. A. Sawyer 1 Corinthians Th rough the Centuries Jeremiah Th rough the Centuries Jorunn Okland Mary Chilton Callaway 2 Corinthians Th rough the Centuries Lamentations Th rough the Centuries Paula Gooder Paul M. Joyce & Diane Lipton Hebrews Th rough the Centuries Ezekiel Th rough the Centuries John Lyons Andrew Mein James Th rough the Centuries Jonah Th rough the Centuries David Gowler Yvonne Sherwood Pastoral Epistles Th rough the Centuries Jay Twomey Esther Through the Centuries Jo Carruthers © by Jo Carruthers blackwell publishing Main Street, Malden, MA - , USA Garsington Road, Oxford OX DQ, UK Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria , Australia Th e right of Jo Carruthers to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act . -

![Prints and Johan Wittert Van Der Aa in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.[7] Drawings, Inv](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4834/prints-and-johan-wittert-van-der-aa-in-the-rijksmuseum-in-amsterdam-7-drawings-inv-254834.webp)

Prints and Johan Wittert Van Der Aa in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.[7] Drawings, Inv

Esther before Ahasuerus ca. 1640–45 oil on panel Jan Adriaensz van Staveren 86.7 x 75.2 cm (Leiden 1613/14 – 1669 Leiden) signed in light paint along angel’s shield on armrest of king’s throne: “JOHANNES STAVEREN 1(6?)(??)” JvS-100 © 2021 The Leiden Collection Esther before Ahasuerus Page 2 of 9 How to cite Van Tuinen, Ilona. “Esther before Ahasuerus” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artwork/esther-before-ahasuerus/ (accessed October 02, 2021). A PDF of every version of this entry is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Esther before Ahasuerus Page 3 of 9 During the Babylonian captivity of the Jews, the beautiful Jewish orphan Comparative Figures Esther, heroine of the Old Testament Book of Esther, won the heart of the austere Persian king Ahasuerus and became his wife (Esther 2:17). Esther had been raised by her cousin Mordecai, who made Esther swear that she would keep her Jewish identity a secret from her husband. However, when Ahasuerus appointed as his minister the anti-Semite Haman, who issued a decree to kill all Jews, Mordecai begged Esther to reveal her Jewish heritage to Ahasuerus and plead for the lives of her people. Esther agreed, saying to Mordecai: “I will go to the king, even though it is against the law. -

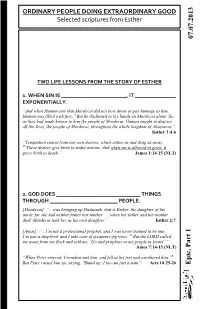

07.07.13 Final

ORDINARY PEOPLE DOING EXTRAORDINARY GOOD Selected scriptures from Esther 07.07.2013 TWO LIFE LESSONS FROM THE STORY OF ESTHER 1. WHEN SIN IS ________________________, IT _______________ EXPONENTIALLY. “And when Haman saw that Mordecai did not bow down or pay homage to him, Haman was filled with fury. 6 But he disdained to lay hands on Mordecai alone. So, as they had made known to him the people of Mordecai, Haman sought to destroy all the Jews, the people of Mordecai, throughout the whole kingdom of Ahasuerus.” Esther 3:4-6 “Temptation comes from our own desires, which entice us and drag us away. 15 These desires give birth to sinful actions. And when sin is allowed to grow, it gives birth to death.” James 1:14-15 (NLT) 2. GOD DOES _______________________________ THINGS THROUGH _________________________ PEOPLE. [Mordecai]: “…was bringing up Hadassah, that is Esther, the daughter of his uncle, for she had neither father nor mother. ….when her father and her mother died, Mordecai took her as his own daughter.” Esther 2:7 [Amos]: “…I’m not a professional prophet, and I was never trained to be one. I’m just a shepherd, and I take care of sycamore-fig trees. 15 But the LORD called me away from my flock and told me, ‘Go and prophesy to my people in Israel.’” Amos 7:14-15 (NLT) “When Peter entered, Cornelius met him, and fell at his feet and worshiped him. 26 But Peter raised him up, saying, "Stand up; I too am just a man.” Acts1 10:25-26Part Epic, MAKE IT PERSONAL: 1. -

A REWRITTEN BIBLICAL BOOK the So-Called Lucianic

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN THE ‘LUCIANIC’ TEXT OF THE CANONICAL AND APOCRYPHAL SECTIONS OF ESTHER: A REWRITTEN BIBLICAL BOOK The so-called Lucianic (L) text of Esther is contained in manuscripts 19 (Brooke-McLean: b’), 93 (e2), 108 (b), 319 (y), and part of 392 (see Hanhart, Esther, 15–16). In other biblical books the Lucianic text is joined by manuscripts 82, 127, 129. In Esther this group is traditionally called ‘Lucianic’ because in most other books it represents a ‘Lucianic’ text, even though the ‘Lucianic’ text of Esther and that of the other books have little in common in either vocabulary or translation technique.1 The same terminology is used here (the L text). Some scholars call this text A, as distinct from B which designates the LXX.2 Brooke-McLean3 and Hanhart, Esther print the LXX and L separately, just as Rahlfs, Septuaginta (1935) provided separate texts of A and B in Judges. Despite the separation between L and the LXX in these editions, the unique character of L in Esther was not sufficiently noted, possibly because Rahlfs, Septuaginta does not include any of its readings. Also HR 1 Scholars attempted in vain to detect the characteristic features of LXXLuc in Esther as well. For example, the Lucianic text is known for substituting words of the LXX with synonymous words, and a similar technique has been detected in Esther by Cook, “A Text,” 369–370. However, this criterion does not provide sufficient proof for labeling the L text of Esther ‘Lucianic,’ since the use of synonymous Greek words can be expected to occur in any two Greek translations of the same Hebrew text. -

The Origins of Beowulf Between Anglo-Saxon Tradition and Christian Latin Culture

The Origins of Beowulf Between Anglo-Saxon Tradition and Christian Latin Culture Autor: Rubén Abellán García Tutor: Agustí Alemany Villamajó Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2019-2020 Index 1. Introduction .............................................................................................................. 2 1.1. The structure and transmission of Beowulf. ......................................................... 2 1.2. Literacy context during the creation period of Beowulf ....................................... 3 1.3. Historical Oral-formulaic and literacy research in Old studies ............................. 3 2. Latin Tradition in Beowulf ........................................................................................ 5 2.1. Latin syntax in Beowulf ...................................................................................... 5 2.2. Literary devices .................................................................................................. 6 2.2.1. Alliteration ...................................................................................................... 7 2.2.2. Formulas .......................................................................................................... 7 2.2.3. Compounding and Kennings ............................................................................ 8 2.2.4. Rhymes............................................................................................................ 8 2.2.5. Litotes and irony ............................................................................................. -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

Haman the Heartless Esther 3 Intro

Haman the Heartless 3) You begin to understand Haman’s Esther 3 hatred for the Jews Intro: • He was a descendant of those A) In chapter 1 we discussed …. who attacked a weary Israel after 1) The king and his corruption they fled from Egypt 2) Queen Vashti and her character • God delivered them into the hands 3) The world and its ungodly counsel of Israel B) In chapter 2 we continued with …. • Saul didn’t obey and utterly 1) The lonely problem of the king destroyed them 2) The procedure to find a queen • They now are facing the results of 3) The providence of God through it all this disobedience • We ended with King Ahasuerus’ 4) A neat thing to acknowledge is …. life being spared because of • Saul from the tribe of Benjamin, Mordecai failed to destroy the Amalekites C) In chapter 3 our narrative introduces • But Mordecai, also a Benjamite, another character, Haman took up the battle and defeated 1) Haman is an “ancient day” Hitler Haman • He is waiting 5) Everything about Haman is hateful 2) Haman is an Agagite (from empire • You can’t find a good quality in known as Agag) anything written about him • Agag was king of the Amalekites • Proverbs 6:16-19 “These six things • I Samuel 15:2 “Thus saith doth the Lord hate: yea, seven are the Lord of hosts, I remember that an abomination unto him: A proud which Amalek did to Israel, how he look, a lying tongue, and hands that laid wait for him in the way, when shed innocent blood, An heart that he came up from Egypt.” deviseth wicked imaginations, feet • I Samuel 15:8 “And he took Agag that be swift in running to mischief, the king of the Amalekites alive, A false witness that speaketh lies, and utterly destroyed all the people and he that soweth discord among with the edge of the sword.” brethren.” • Saul actually disobeyed His Lord in • You will notice each quality as you not destroying all the Amalekites read of Haman D) Let’s study and see several aspects C) His vanity (Vs. -

The Treasure Principle

The Treasure Principle Ch 2: Ahasuerus approves a plan to find a new queen by searching the The Treasure of Influence empire (25 mill women) for the most graceful & stunning woman. Narrow the Esther 1:1-10:3 search down to 400 (Josephus), & give those women 1 year at the spa, becoming as gorgeous as possible before the king makes his final pick. Intro: Today’s message will be quite different than any I’ve preached before. Normally, we grab a few verses of the bible & work through them in an Among the Jews still living near the palace, we find a man named Mordecai. outline format. However, today, I am going to cover an entire book of the Bible (don’t leave), making observations & applications. If you’d like to join “He was bringing up Hadassah, that is Esther, the daughter of his uncle, for me in this journey, you can take your Bible (seatback or online) & find the she had neither father nor mother. The young woman had a beautiful figure Old Testament book of Esther. and was lovely to look at, and when her father and her mother died, Mordecai took her as his own daughter.” Esther 2:7 Setting: 2,500 years ago (486 BC) in the Persian Empire, the son of King Darius, the grandson of Cyrus the Great was preparing to invade Greece to Esther was chosen as one of the 400 young women who would receive a year settle an old score for his deceased father. Most of history remembers this of spa treatments in preparation to meet the king as a potential queen. -

Raoul Walsh to Attend Opening of Retrospective Tribute at Museum

The Museum of Modern Art jl west 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart NO. 34 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RAOUL WALSH TO ATTEND OPENING OF RETROSPECTIVE TRIBUTE AT MUSEUM Raoul Walsh, 87-year-old film director whose career in motion pictures spanned more than five decades, will come to New York for the opening of a three-month retrospective of his films beginning Thursday, April 18, at The Museum of Modern Art. In a rare public appearance Mr. Walsh will attend the 8 pm screening of "Gentleman Jim," his 1942 film in which Errol Flynn portrays the boxing champion James J. Corbett. One of the giants of American filmdom, Walsh has worked in all genres — Westerns, gangster films, war pictures, adventure films, musicals — and with many of Hollywood's greatest stars — Victor McLaglen, Gloria Swanson, Douglas Fair banks, Mae West, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Marlene Dietrich and Edward G. Robinson, to name just a few. It is ultimately as a director of action pictures that Walsh is best known and a growing body of critical opinion places him in the front rank with directors like Ford, Hawks, Curtiz and Wellman. Richard Schickel has called him "one of the best action directors...we've ever had" and British film critic Julian Fox has written: "Raoul Walsh, more than any other legendary figure from Hollywood's golden past, has truly lived up to the early cinema's reputation for 'action all the way'...." Walsh's penchant for action is not surprising considering he began his career more than 60 years ago as a stunt-rider in early "westerns" filmed in the New Jersey hills. -

For Such a Time As This 1 Introduction

For Such a Time as This (Esther 4:7-17) To me, this is a very personal and a very touching moment, because twenty-nine years ago when I first arrived at the United States I had never dreamed that one day I would be standing here to preach in a language that is not my mother tongue. I am very thankful for having this opportunity. And thank you for bearing with me. 1 Introduction The Book of Esther is a very peculiar book in the Bible. So eccentric is the book that there are many debates among Bible scholars on whether this book should have been included in the old testament in the first place. After all, the keyword “God” or “Lord” which should be of such paramount significance has never occurred even once in the entire writing, not to mention the absence of other spiritual activities such as “worshiping,” “praying,” or “offering.” It has been argued that the form of the story seems closer to that of a romance than a work of history, that the chronicle is a charming love story indeed, with exciting plots, but of few true spiritual values. Maybe those scholars do have their points which cannot easily be com- prehended by lay-persons such as you and me. But if we put ourselves in the story and think about it for a moment, then it is not difficult to dis- cover that it is precisely under such an environment of “Godlessness” that this book brings forth a powerful message. The message is this — Yes, darkness is around us! Yes, enemies are amassing and prevailing! Yes, the surroundings of us are full of dangers and evils. -

The Chapters of Esther

Scholars Crossing An Alliterated Outline for the Chapters of the Bible A Guide to the Systematic Study of the Bible 5-2018 The Chapters of Esther Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/outline_chapters_bible Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "The Chapters of Esther" (2018). An Alliterated Outline for the Chapters of the Bible. 34. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/outline_chapters_bible/34 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the A Guide to the Systematic Study of the Bible at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in An Alliterated Outline for the Chapters of the Bible by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Esther SECTION OUTLINE ONE (ESTHER 1-2) King Xerxes deposes Queen Vashti for refusing to appear before him at a banquet. A search is made for a new queen, and Esther is selected. Her adoptive father Mordecai becomes a palace official. He overhears a plot to assassinate the king, and he reports it to Esther and saves the king's life. I. THE REJECTION OF VASHTI (1:1-22): King Xerxes of Persia is rebuffed by his queen during one of his banquets, so he deposes her. A. A banquet for his provincial officials (1:1-4): King Xerxes gives a banquet for all his princes and officials from his 127 provinces, stretching from India to Ethiopia.