A BLACK HEART the Work of Thomas Jefferson Bowen Among Blacks In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"A Fine Field": Rio De Janeiro's Journey to Become a Center of Strength for the LDS Church

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2016-03-01 "A Fine Field": Rio de Janeiro's Journey to Become a Center of Strength for the LDS Church Garret S. Shields Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Religion Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Shields, Garret S., ""A Fine Field": Rio de Janeiro's Journey to Become a Center of Strength for the LDS Church" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 6213. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/6213 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. “A Fine Field”: Rio de Janeiro’s Journey to Become a Center of Strength for the LDS Church Garret S. Shields A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Alonzo L. Gaskill, Chair Mark L. Grover Jared Ludlow Department of Religious Education Brigham Young University March 2016 Copyright © 2016 Garret S. Shields All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT “A Fine Field”: Rio de Janeiro’s Journey to Become a Center of Strength for the LDS Church Garret S. Shields Department of Religious Education, BYU Master of Arts The purpose of this work is to chronicle the growth of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil from its earliest beginnings in the late 1930s to the events surrounding the revelation on the priesthood in 1978. -

Transnational Pentecostal Connections: an Australian Megachurch and a Brazilian Church in Australia Introduction I Arrived at Th

Transnational Pentecostal Connections: an Australian Megachurch and a Brazilian Church in Australia Introduction1 I arrived at the Comunidade Nova Aliança (CNA) church on a Sunday, a little bit before the 7 pm service. From the street I could hear loud music playing. When I crossed the front door I unexpectedly found myself in a nightclub: the place was dark, lit only by strobe lights, and there was a stage with large projection screens on each side. People were chatting animatedly in the adjacent foyer. They were all young, mostly in their late teens. A young woman came to chat and asked if I were okay, if I knew anyone. Prompted by me, she took me to pastor Henrique and his wife, Denise, whom I had spoken to on the phone the previous Sunday. We exchanged pleasantries and they excused themselves because service was about to start. We all moved on to the audience seats and five young people climbed onto the stage. There were three young males (a guitar and a bass players, and a drummer) and two female singers. Pastor Henrique asked the crowd in Portuguese: “Who wants to be blessed by God?” Everyone raised their arms and replied “yes”. The band started playing worship music. For an hour there was one song praising Jesus after another. Songs were in Portuguese but real-time telecasts of the band and the song lyrics translated into English were beamed onto the screens beside the stage. Everyone was dancing and singing together with the band. Many raised their arms, some kept their eyes closed, others were crying with their hands on their hearts, a few dropped to their knees overwhelmed by emotion. -

Digital Commons @ Fuller the Semi (07-01-2002)

Fuller Theological Seminary Digital Commons @ Fuller The SEMI (2001-2010) Fuller Seminary Publications 7-1-2002 The Semi (07-01-2002) Fuller Theological Seminary Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fuller.edu/fts-semi-6 Recommended Citation Fuller Theological Seminary, "The Semi (07-01-2002)" (2002). The SEMI (2001-2010). 54. https://digitalcommons.fuller.edu/fts-semi-6/54 This Periodical is brought to you for free and open access by the Fuller Seminary Publications at Digital Commons @ Fuller. It has been accepted for inclusion in The SEMI (2001-2010) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Fuller. For more information, please contact [email protected]. | iDpApY pij* ? cp THEOLOGICAL $EMiNANV “Do not the most moving moments of our lives And us all without words?” —Marcel Marceau— The world's greatest_____at Fuller? see page B Summer 2DD2 • July Issue Drinking from the World Cup www.fuller.edu/studentJife/5EIVII/semi.html A Perspective by Tim Klingler luring the month of June, a single event captivated virtually the entire globe. From Burma to Burkina Faso, Bolivia to Bosnia, 0 Belgium to Belize, the world fixed its attention on the 2002 World Cup soccer tournament. An estimated three-and-a-half billion people tuned in to watch the tournament. For the final match, one-and-a-half billion people gathered around TV screens in homes, bus stations, bars, restaurants, churches, and parks to watch Brazil defeat Germany 2-0 for its fifth cham pionship title. While most of the US population abstained from partaking of the Cup, a significant percentage of the Fuller community imbibed and participated in the quadrennial euphoria of the global community. -

If I Give My Soul: Pentecostalism Inside of Prison in Rio De Janeiro

If I Give My Soul: Pentecostalism inside of Prison in Rio de Janeiro. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Andrew Reine Johnson IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Dr. Penny Edgell, Adviser August 2012 Copyright © 2012 Andrew Reine Johnson All rights reserved Acknowledgments First, I would like to thank my parents, Gordon and Hope, my brother Peter and fiancé Rosane. I am so grateful for each one of them and thankful for their unwavering love. I would also like to thank my adviser Penny Edgell for the mentoring, guidance and persistent support she has provided over the last five years. I want to thank the other members of my dissertation committee, Chris Uggen, Joshua Page and Curtiss DeYoung, for the substantial contributions each one has made to this project. I thank Elizabeth Sussekind for sponsoring my research in Rio de Janeiro and for her insights on the Brazilian Criminal Justice system. I could not have gained access to the prisons and jails without the help and friendship of Antonio Carlos Costa, president of Rio de Paz, and I admire his work and vision for those on the margins of Rio de Janeiro. I also want to thank Darin Mather and Arturo Baiocchi for their friendship as well as their sociological and grammatical insights. I would like to thank Noah Day for his generosity during tight times and Valdeci Ferreira for allowing me to stay in the APAC prison system. Finally, I would like to thank the inmates, ex-prisoners and detainees who participated in this project for the hospitality and trust they showed me during the fieldwork for the project. -

8-28-2013 Full Paper

16 Back pew NORTH COUNTRY CATHOLIC The Diocese of Ogdensburg Volume 68, Number 15 AUG. 28, 2013 INSIDE YOUNG CATHOLIC VOICE THIS ISSUE Bishop announces NONORTHRTH C COUOUNTRYNTRY changes in clergy assignments l PAGE 3 Catholic Charities responds to human trafficking l PAGE 10 CATHOLIC AUG. 28, 2013 Faith ‘not about decorating life’ VATICAN CITY (CNS) - Faith isn't itors in St. Peter's Square. God had to be the "basic cri- Living a truly Christian life POPE FRANCIS’ something decorative one Pope Francis' Angelus ad- teria of life," Pope Francis can lead to division, even adds to life, but is a commit- dress included an explana- told thousands of people within families, he said. "But REPRESENTATIVE ment that involves making tion of a passage from the gathered under the midday attention: It's not Jesus who choices that may require sac- day's Gospel reading from sun to pray with him. divides. To preside at rifice, Pope Francis said. Luke in which Jesus tells his "Following Jesus means re- “He sets out the criteria: Faith "is not decorating disciples: "Do you think that nouncing evil, selfishness Live for oneself or for God Year of Faith your life with a bit of religion I have come to establish and choosing goodness, and others, ask to be served as if life were a cake that you peace on the earth? No, I tell truth and justice even when or serve; obey one's ego or Mass in LP decorate with cream," the you, but rather division." that requires sacrifice and re- obey God -- it is in this sense Kelly Donnelly and Jen Campbell of Plattsburgh were among the millions of youth adults from around the looks Rio de Janeiro. -

INTRODUCTION 1. the Sociologist of Religion, David Martin Shows the Very Different Forms of Secularization That Took Place Depen

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. The sociologist of religion, David Martin shows the very different forms of secularization that took place depending on whether the Church constituted the 'monopoly' of power, as in France and Scandinavia, or to a lesser extent in England with the Dissent, or whether there was no such direct connection, as in the United States for example. He explains how, starting from the American model, 'emotional' religion was able to spread in the Third World, as a transformation of Methodism into Pentecostalism (Martin, 1978, 1990). 2. Daniele Hervieu-Leger does this for the sake of provocation in 'Renouveaux emotionnels contemporains' (Hervieu-Leger, in Champion and Hervieu-Leger, 1990, pp. 217-48). 3. Historical Protestants often have the same negative reaction as Catholics do towards new Churches, especially Pentecostal ones (Martin, 1990, p. 30). 4. On the notions of 'political language' and 'acceptability', see Faye (1972). 5. Perhaps this was true of Puritanism in its early stage as well. Puritanism also emerged as a valorization of fervour and piety. On the other hand, there was in it a refusal to abandon oneself to emotions. 6. This is political theology understood in its political dimension, a dimension which is totally distinct in its presuppositions and its methodology from the theological dimension, to which liberation theology indirectly belongs. 7. In this volume of selected texts by Novalis, the Schlegel brothers, Adam Miiller, Schleiermarcher, and so on, the author views polit ical Romanticism mainly as a reaction against the French Revolution. 8. See Barret-Kriegel (1979). The author's thesis on the Romantic origin of totalitarianism - a thesis which, with respect to Nazism, is moreover akin to that of Lukacs in The Destruction of Reason - is at times outrageously far-fetched. -

2021 Book of Reports

BOOK OF REPORTS OF THE 2021 SOUTHERN BAPTIST CONVENTION prepared for the One Hundred Sixty-Third Session One Hundred Seventy-Sixth Year meeting in Nashville, Tennessee June 15-16, 2021 2021 CONVENTION OFFICERS President J. D. Greear First Vice President Marshal Ausberry Second Vice President Noe Garcia Recording Secretary John L. Yeats Acting Registration Secretary Don Currence Treasurer Ronnie W. Floyd FUTURE SBC ANNUAL MEETING SITES Anaheim, California – June 14–15, 2022 Charlotte, North Carolina – June 13–14, 2023 Indianapolis, Indiana – June 11–12, 2024 Dallas, Texas – June 10-11, 2025 Orlando, Florida – June 9–10, 2026 FOREWORD _________________________________________ We are Great Commission Baptists. The Great Commission is what our churches do above all things. The sacrificial generosity of our churches through the Cooperative Program demonstrates the priority of sharing the Gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ in great cities like Lusaka, Phnom Penh, Cebu City, Pretoria, or Mosul. At the same time, Great Commission Baptists shelter the rescued child from sex traffickers. At the same time, we disciple collegiates on the university campuses of North America and start churches in places like Bozeman, Bismarck, Boston, and Birmingham. Great Commission Baptists live on mission with God. If we ever move away from the main themes of extraordinary prayer, soul-winning, and missional engagement, then the three-cord rope that binds us begins to shred into a past memory of what once was. Great Commission Baptists have the whole world on their hearts and passionately live to do their part in bringing in the harvest of souls who have yet to taste of the grace of God. -

The Journal of Volume 21, 2019

The Journal of Florida Baptist Heritage Volume 21, 2019 THE JOURNAL OF FLORIDA BAPTIST HERITAGE Published by the FLORIDA BAPTIST HISTORICAL SOCIETY Donald S. Hepburn, Secretary-Treasurer Penny Baumgardner, Administrative Ministry Assistant PO Box 95 Graceville, Florida 32440 Board of Directors The State Board of Missions of the Florida Baptist State Convention elects the Board of Directors. Jerry Chumley David Lema Lake Mystic Hialeah David Elder Roger Richards St. Augustine Graceville Donald Hepburn J. Thomas Green Jacksonville Executive Director-Treasurer Florida Baptist Convention The Florida Baptist Historical Society is a Cooperative Pro gram-funded ministry of the Florida Baptist Convention. COVER ILLUSTRATION: Seventeen delegates, representing the three Baptist associations within Florida, met in the Richard Johnson Mays’ home on November 20,1854, to organize the Florida Baptist State Convention. [Illustration by John Lane] Volume 21/2019. Copyright 2019. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Preface 4 Notable Legacies 6 125 Years of Ministry Service 8 2019 Baptist Heritage Award 12 Florida Baptist Legacy Leaders 1) The Biblical Theology of Christian Leadership by Benjamin Forrest, EdD 14 2) James Mc Donald - The Legacy of a North Florida Pioneer Itinerant Missionary by James C. Bryant, PhD 28 3) Richard Johnson Mays - The Legacy “Father” of the Florida Baptist State Convention by T. Phil Heard 48 4) Lulu Sparkman Terry — A Floridian’s 45 Year Legacy of Missionary Service in Brazil by Donald S. Hepburn 66 5) Ismael Negrin — Laid Foundations for Florida Baptist Hispanic Congregations by Barbara Little Denman 84 6) Jeremiah M. Hayman — The Legacy of a Central Florida Pioneer Missionary-Preacher by Hampton Dunn 100 Table of Contents 7) Frank Fowler — The Legacy of a Native Floridian International Missionary by Mark A. -

A Study of the Activities and Results of the Protestant Foreign Missionary Movement in the United States of Brazil Robert Martin Farra University of Nebraska at Omaha

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 8-1960 Protestantism in Brazil: A study of the activities and results of the Protestant foreign missionary movement in the United States of Brazil Robert Martin Farra University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Farra, Robert Martin, "Protestantism in Brazil: A study of the activities and results of the Protestant foreign missionary movement in the United States of Brazil" (1960). Student Work. 337. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/337 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PROTESTANTISM IN BRAZIL: A STUDY OF THE ACTIVITIES AND RESULTS OF THE PROTESTANT FOREION MISSIONARY MOVEMENT IN THE UNITED STATES OF BRAZIL A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of History University of Omaha In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Robert Martin Farra August i960 UMI Number: EP72979 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP72979 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

Y, Guaymi Indians. + "1 Did Skin Grafts With

REDIUNAL OFFICES ATLANTA Walker L. Knight, Editor, 161 Spring Street, N.W., Atlanta, &or& 303 03, Telephone (404) 523-2593 DALLM R. T. McCa+tney, Edltm, 103 Bllptid Building, Dallas, Texas 75 201, Telephone (214) RI 1-1996 WAIBHINQTUN W. Blang Gm~att,Bdltw, 200 Mmyhd Am., NJ., Wachington, D.C. 20002, Telebhons (202) 5ff.4226 May 29, 1967 BUREAU BAPTlIST UUNDAY HCHOOL BOARD Lynn M. Dav* Jf., Chief, 127 Ninth Am., N., Noshvills, Tenn. 37203,, Telephonr (615) 254-1631 FANNING SAYS SBC IiAY DIE WITHOUT INTEGRATION By Roy Jcnnings FIIL.Il BEACH (BP)- he Southern Baptist Convcntion will die unless its churches open their docrs to all races and church members becomc concerned about the necds of people, Buckner Fanning, a San Antonio, Tox., pastor, prcdictcd bcre, In an address to the Southern Baptist Pastors1 Conference, Fanning, 41-year-old pastor of San Antonio's Trinity Baptist Church, called Ear an cxprcssion cf Christian love , which would find church mcmbers involved as Christians on a personal level in all of the f activities of their community. Speaking on the strafegy of penetrztion, Fanning told how his church had turned from the traditional approach of inspiration to one of action, then made this prediction: "Unless our churches become placcs of worship where people of all raccs and classcs meet togcther in Chri~tthrough worship and fellowship; unleos we becomc great springs of new life flowing out from our sanctuaries into the hot parched prairies of hurucn nccd; unless we Baptiats experience a change of attitude and a change in direction, then we too will pass into the graveyard of denominations., . -

AMW EDITION.Cdr

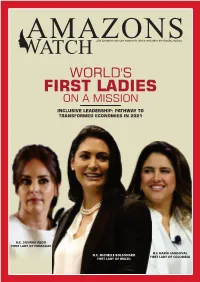

AMA..theZ foremost voice forO women in AfricaN and other developingS regions. ATCH WORLD'S FIRST LADIES ON A MISSION INCLUSIVE LEADERSHIP: PATHWAY TO TRANSFORMED ECONOMIES IN 2021 H.E. SILVANA ABDO FIRST LADY OF PARAGUAY H.E MARÍA SANDOVAL H.E. MICHELLE BOLSONARO FIRST LADY OF COLOMBIA FIRST LADY OF BRAZIL Afric n Leadership Magazine A F R I C A N L E A D E R S H I P M A G A Z I N E PERSONS OF THE YEAR 2020 (Virtual Awards Ceremony) February 26th, 2021 [email protected] 52 29 JOGGLING HOME & WORK WITH PANTELLIGENT 45 SURROGACY IN AFRICA – WOMEN POWERING THE SKY: TABOO OR RELIEF? 40 MEET THE LIONESSES OF 65 AFRICA'S AVIATION SECTOR HOW DO I TELL MY KIDS SANTA ISN'T REAL? 48 TRANSFORMING THE LIVES OF POOR WIDOWS WITH 43 RELATIONSHIP ISSUES & SEWING MACHINES EXPERT SOLUTIONS 50 STRENGTHENING THE EMOTIONAL BOND BETWEEN SUDANESE WOMEN CONTINUES 8 PARENTS AND CHILDREN 68 TO PUSH FOR DEMOCRACY 62 56 25 34 From the CEO Advancing Initiatives & Partnerships for Gender Development in 2021 The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed more than anything else, the disproportionate impact of governance and policies on women and children. The pandemic, which has evolved into an unprecedented crisis is heavily affecting the livelihoods, the socio- economic stability, leadership and the security of many families and communities, especially in emerging economies. The uncertainty, and preventive and containment measures against the pandemic have introduced profound disruptions that have had very adverse effects particularly to women on the continent, more than on their male counterparts. -

Hawaii Clergy and Religious Celebrate Jubilees Page 3

NATION HAWAII VATICAN | HAWAII VATICAN Medal of Honor recipient Diocese’s response to Celebrating Pope Francis, soccer fan: listed at Punchbowl also a clergy sexual abuse is the Triduum: Photos These are a few of his sainthood candidate comprehensive, thorough from Holy Week favorite things Page 5 Page 7 Page 12-13 Page 18 HawaiiVOLUME 76, NUMBER 8 CatholicFRIDAY, APRIL 12, 2013 Herald$1 Hawaii clergy and religious celebrate jubilees Page 3 Franciscan Sister William Marie Eleniki, left, and Dominican Sister Mary Mark N. Berdin congratu- late each other on their jubilee celebrations, April 6 at the Co- Cathedral of St. Theresa. Both celebrated 50-year anniversaries of their profession of vows. HCH photo | Darlene Dela Cruz 2 HAWAII HAWAII CATHOLIC HERALD • APRIL 12, 2013 Confirmation schedule, 2013 Hawaii The time after Easter is traditionally “confirmation season” in the dio- Sts. Peter and Paul, Ala Moana: May 26, 6 p.m. cese. Here is the schedule of this year’s confirmation ceremonies as an- Holy Trinity, Kuliouou: June 1, 10 a.m. Catholic nounced by the Office of the Bishop. Bishop Larry Silva is presided over St. Anthony, Kalihi,* Blessed Sacrament, Pauoa: June 1, 6 p.m. 26 ceremonies, vicar general Father Gary Secor is presiding over 19. Herald St. Stephen, Nuuanu: Sept. 29, 9:30 a.m. Newspaper of the Diocese of Honolulu Bishop Larry Silva presiding Founded in 1936 Father Gary Secor, vicar general, presiding Published every other Friday Cathedral of Our Lady of Peace: April 6, 10:30 a.m. PUBLISHER St. George, Waimanalo: April 20, 6 p.m.