M. K. Gandhi's Concern with Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi Warrior of Non-Violence P

SATYAGRAHA IN ACTION Indians who had spent nearly all their lives in South Africi Gandhi was able to get assistance for them from South India an appeal was made to the Supreme Court and the deportation system was ruled illegal. Meantime, the satyagraha movement continued, although more slowly as a result of government prosecution of the Indians and the animosity of white people to whom Indian merchants owed money. They demanded immediate payment of the entire sum due. The Indians could not, of course, meet their demands. Freed from jail once again in 1909, Gandhi decided that he must go to England to get more help for the Indians in Africa. He hoped to see English leaders and to place the problems before them, but the visit did little beyond acquainting those leaders with the difficulties Indians faced in Africa. In his nearly half year in Britain Gandhi himself, however, became a little more aware of India’s own position. On his way back to South Africa he wrote his first book. Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule. Written in Gujarati and later translated by himself into English, he wrote it on board the steamer Kildonan Castle. Instead of taking part in the usual shipboard life he used a packet of ship’s stationery and wrote the manuscript in less than ten days, writing with his left hand when his right tired. Hind Swaraj appeared in Indian Opinion in instalments first; the manuscript then was kept by a member of the family. Later, when its value was realized more clearly, it was reproduced in facsimile form. -

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi's Experiments with the Indian

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi’s Experiments with the Indian Economy, c. 1915-1965 by Leslie Hempson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Co-Chair Professor Mrinalini Sinha, Co-Chair Associate Professor William Glover Associate Professor Matthew Hull Leslie Hempson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5195-1605 © Leslie Hempson 2018 DEDICATION To my parents, whose love and support has accompanied me every step of the way ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF ACRONYMS v GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS vi ABSTRACT vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: THE AGRO-INDUSTRIAL DIVIDE 23 CHAPTER 2: ACCOUNTING FOR BUSINESS 53 CHAPTER 3: WRITING THE ECONOMY 89 CHAPTER 4: SPINNING EMPLOYMENT 130 CONCLUSION 179 APPENDIX: WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 183 BIBLIOGRAPHY 184 iii LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 2.1 Advertisement for a list of businesses certified by AISA 59 3.1 A set of scales with coins used as weights 117 4.1 The ambar charkha in three-part form 146 4.2 Illustration from a KVIC album showing Mother India cradling the ambar 150 charkha 4.3 Illustration from a KVIC album showing giant hand cradling the ambar charkha 151 4.4 Illustration from a KVIC album showing the ambar charkha on a pedestal with 152 a modified version of the motto of the Indian republic on the front 4.5 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing the charkha to Mohenjo Daro 158 4.6 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing -

Chapter I Introduction

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Nonviolence is the pillar of Gandhi‘s life and work. His concept of nonviolence was based on cultivating a particular philosophical outlook and was integrally associated with truth. For him, nonviolence not just meant refraining from physical violence interpersonally and nationally but refraining from the inner violence of the heart as well. It meant the practice of active love towards one‘s oppressor and enemies in the pursuit of justice, truth and peace; ―Nonviolence cannot be preached‖ he insisted, ―It has to be practiced.‖ (Dear John, 2004). Non Violence is mightier than violence. Gandhi had studied very well the basic nature of man. To him, "Man as animal is violent, but in spirit he is non-violent.‖ The moment he awakes to the spirit within, he cannot remain violent". Thus, violence is artificial to him whereas non-violence has always an edge over violence. (Gandhi, M.K., 1935). Mahatma Gandhi‘s nonviolent struggle which helped in attaining independence is the biggest example. Ahimsa (nonviolence) has been part of Indian religious tradition for centuries. According to Mahatma Gandhi the concept of nonviolence has two dimensions i.e. nonviolence in action and nonviolence in thought. It is not a negative virtue rather it is positive state of love. The underlying principle of non- violence is "hate the sin, but not the sinner." Gandhi believes that man is a part of God, and the same divine spark resides in all men. Since the same spirit resides in all men, the possibility of reforming the meanest of men cannot be ruled out. -

Domestic Violence Against Women in India: a Case Study

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN INDIA: A CASE STUDY ABSTRACT OF THE /^C THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF fioctor of $I)ilDs;opl)p •^ ^'^ IN (, POLITICAL SCIENCE BY RAHAT ZAMANI Under the Supervision of Dr. Rachana Kanshal DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ALJGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2009 ABSTRACT Today human beings live in the so-called civilized and democratic society that is based on the principles of equality and freedom for all. It automatically results into the non-acceptance of gender discrimination in principle. Therefore, various International Human Rights norms are in place that insist on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women and advocate equal rights for women. Womens' year, women decade etc. are observed that led to the creation of mass awareness and sensitization of people about rights of women. Many steps are taken by the government in the form of various policies and programmes to promote the status of women and to realize women's rights. But despite all the efforts, the basic issue that threatens and endangers the very existence of women is the issue of domestic violence against women. John Stuart Mill put it into his book 'the subjection of women' in 1869 that, 'marriage should be thought of as a partnership of equals analogous to a business partnership and the family not a school of despotism but the real school of the virtues of freedom'. Contrary to this women who constitute about half of the world's population are the worst victim of violence and exploitation within home. -

Gandhiji on VILLAGES Selected and Compiled with an Introduction By

Gandhiji on VILLAGES Selected and Compiled with an Introduction by Divya Joshi GANDHI BOOK CENTRE Bombay Sarvodaya Mandal 299 Tardeo Road, Nana Chowk Mumbai 400007 INDIA Tel.: 2387 2061 Email: [email protected] www.mkgandhi.org MANI BHAVAN GANDHI SANGRAHALAYA MUMBAI Published with the financial assistance received from the Department of Culture, Government of India. Published with the permission of The Navajivan Trust, Ahmedabad - 380 014 First Edition 1000 copies : 2002 Set in 11/13 Point Times New Roman by Gokarn Enterprises, Mumbai Invitation Price : Rs. 30.00 Published by Meghshaym T. Ajgaonkar, Executive Secretary Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya 19, Laburnum Road, Gamdevi, Mumbai 400 007 Tel. No. 2380 5864, Fax. No. 2380 6239 E-mail: [email protected] and Printed at Mouj Printing Bureau, Mumbai 400 004. Gandhiji on VILLAGES PREFACE Gandhiji's life, ideas and work are of crucial importance to all those who want a better life for humankind. The political map of the world has changed dramatically since his time, the economic scenario has witnessed unleashing of some disturbing forces, and the social set-up has undergone a tremendous change. The importance of moral and ethical issues raised by him, however, remain central to the future of individuals and nations. Today we need him, more than before. Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya has been spreading information about Gandhiji's life and work. A series of booklets presenting Gandhiji's views on some important topics is planned to disseminate information as well as to stimulate questions among students, scholars, social activists and concerned citizens. We thank Government of India, Ministry of Tourism & Culture, Department of Culture, for their support. -

Martin Luther and Coretta Scott King Library

At James Madison University Martin Luther and Coretta Scott King Library Book Catalog Abu-Nimer, Mohammed. 2003. Nonviolence and Peace Building in Islam: Theory and Practice. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. Ackerman, Peter and Jack Duvall. 2000. A Force More Powerful: A Century of Nonviolent Conflict. New York: Palgrave. Agrawal, A. N. 2005. The Rupa Book of Gandhi Quiz. New Delhi: Rupa. Alter, Joseph S. 2000. Gandhi’s Body: Sex, Diet, and the Politics of Nationalism. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Andrews, Charles F. 2003. Mahatma Gandhi: His Life and Ideas. Woodstock: First SkyLight Paths Publishing. Arendt, Hannah. 1970. On Violence. New York: Harcourt Brace. Arnold, David. 2001. Gandhi: Profiles in Power. Harlow: Pearson Education. Ashe, Geoffrey. 1968. Gandhi: A Biography. New York: Cooper Square Press. Attenborough, Richard, ed. 1982. The Words of Gandhi. New York: Newmarket Press. Badruddin. 2003. Global Peace and Anti-Nuclear Movements. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. Balagangadhara, S. N. 2005. “The Heathen in His Blindness”: Asia, the West and the Dynamic of Religion. New Delhi: Manohar. Barak, Gregg. 2003. Violence and Nonviolence: Pathways to Understanding. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. 2 / King Library Book Catalog Barash, David P., ed. 2000. Approaches to Peace: A Reader in Peace Studies. New York: Oxford University Press. Batra, Shakti, ed. N.d. The Quintessence of Gandhi in His Own Words. New Delhi: Madhu Muskan Publications. Betai, Ramesh S. 2002. Gita and Gandhiji. New Delhi: Gyan Publishing. Bharucha, Rustom. 1993. The Question of Faith. New Delhi: Orient Longman. Bloom, Irene, J. Paul Martin, and Wayne L. Proudfoot, eds. 1996. Religious Diversity and Human Rights. -

Everyman's A… B… C… of GANDHI

Everyman’s a… b… c… of GANDHI Everyman, I will go with thee, and be thy guide, in thy most need to go by thy side All quotations of Mahatma Gandhi selected from his writings are reproduced with permission of Navajivan Trust Compiled by Mahendra Meghani First Published: May 2007 Published by: Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust, Ahmedabad And Lokmilap Trust P. Box 23 (Sardarnagar), Bhavnagar 364001, Gujarat Tel. (0278)2566 402 | email: [email protected] Everyman’s a… b… c… of GANDHI Dedicated to them — Hark to the thunder, hark to the tramp — a myriad army comes! An army sprung from a hundred lands, speaking a hundred tongues! ... We come from the fields, we come from the forge, we come from the land and sea Chanting of brotherhood, chanting of freedom, dreaming the world to be -... Upton Sinclair www.mkgandhi.org Page 1 Everyman’s a… b… c… of GANDHI COMPILER'S NOTE THE COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATMA GANDHI have been published in a hundred volumes. Numerous selections from Gandhi's writings have been compiled by editors in many countries. This process must continue till there comes along a single handy publication which, through translations in the world's major languages, might attract, inspire and move millions across the world. This little book is a humble effort in that direction. M. M. www.mkgandhi.org Page 2 Everyman’s a… b… c… of GANDHI JANUARY 1 The acts of men who have come out to serve or lead have always been misunderstood. To put up with these misrepresentations and to stick to one's guns, come what might — this is the essence of the gift of leadership. -

Jagjivan Ram-Pub-4A

ADDRESSES* AT THE UNVEILING OF THE STATUE OF SHRI JAGJIVAN RAM On 25 August 1995, a statue of the former Deputy Prime Minister of India and eminent parliamentarian, Babu Jagjivan Ram was unveiled at the Entrance Hall of the Lok Sabha Lobby in Parliament House by the President of India, Dr. Shanker Dayal Sharma. The statue has been sculpted by the renowned artist, Shri Ram Sutar. The ceremony was followed by a meeting in the Central Hall which was attended by a distinguished gathering. President, Dr. Shanker Dayal Sharma, the Vice-President and Chairman, Rajya Sabha, Shri K.R. Narayanan, the Prime Minister, Shri P.V. Narasimha Rao, the Speaker, Lok Sabha, Shri Shivraj V. Patil and the daughter of Shri Jagjivan Ram, Smt. Meira Kumar addressed the gathering on the occasion. The texts of the Addresses delivered on the occasion are reproduced below. ADDRESS BY THE PRESIDENT OF INDIA, DR. SHANKER DAYAL SHARMA** Shri K.R. Narayanan, Honourable Vice-President of India, Shri P.V. Narasimha Rao, Prime Minister of India, Shri Shivraj V. Patil, Honourable Speaker, Respected Smt. Indrani Ramji, Honourable Members of the Union Council of Ministers, Leaders of the Opposition, Honourable Members of Parliament, Respected Freedom Fighters, Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen: We have gathered here today to pay our respects to Babu Jagjivan Ram, a champion of human rights and dignity and one of the great social reformers of our time. As a representative of the masses, a member of our Constituent Assembly and of successive Parliaments and Governments, Jagjivan Ramji had a profound influence in shaping contemporary India. -

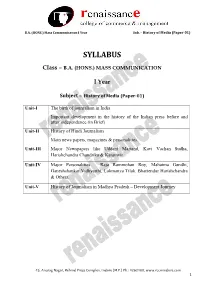

BA (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year

B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) SYLLABUS Class – B.A. (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year Subject – History of Media (Paper-01) Unit-I The birth of journalism in India Important development in the history of the Indian press before and after independence (in Brief) Unit-II History of Hindi Journalism Main news papers, magazines & personalities. Unit-III Major Newspapers like Uddant Martand, Kavi Vachan Sudha, Harishchandra Chandrika & Karamvir Unit-IV Major Personalities – Raja Rammohan Roy, Mahatma Gandhi, Ganeshshankar Vidhyarthi, Lokmanya Tilak, Bhartendur Harishchandra & Others. Unit-V History of Journalism in Madhya Pradesh – Development Journey 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) UNIT-I History of journalism Newspapers have always been the primary medium of journalists since 1700, with magazines added in the 18th century, radio and television in the 20th century, and the Internet in the 21st century. Early Journalism By 1400, businessmen in Italian and German cities were compiling hand written chronicles of important news events, and circulating them to their business connections. The idea of using a printing press for this material first appeared in Germany around 1600. The first gazettes appeared in German cities, notably the weekly Relation aller Fuernemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien ("Collection of all distinguished and memorable news") in Strasbourg starting in 1605. The Avisa Relation oder Zeitung was published in Wolfenbüttel from 1609, and gazettes soon were established in Frankfurt (1615), Berlin (1617) and Hamburg (1618). -

Gandhi ´ Islam

tabah lectures & speeches series • Number 5 GANDHI ISLAM AND THE PRINCIPLES´ OF NON-VIOLENCE AND ATTACHMENT TO TRUTH by KARIM LAHHAM I GANDHI, ISLAM, AND THE PRINCIPLES OF NON-VIOLENCE AND ATTACHMENT TO TRUTH GANDHI ISLAM AND THE PRINCIPLES´ OF NON-VIOLENCE AND ATTACHMENT TO TRUTH by KARIM LAHHAM tabah lectures & speeches series | Number 5 | 2016 Gandhi, Islam, and the Principles of Non-violence and Attachment to Truth ISBN: 978-9948-18-039-5 © 2016 Karim Lahham Tabah Foundation P.O. Box 107442 Abu Dhabi, U.A.E. www.tabahfoundation.org All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any manner without the express written consent of the author, except in the case of brief quotations with full and accurate citations in critical articles or reviews. This work was originally delivered as a lecture, in English, at the Cambridge Muslim College, Cambridge, England, on 11 March 2015 (20 Jumada I 1436). iN the Name of allah, most beNeficeNt, most merciful would like to speak a little tonight about what might at first be seen as incongruous I topics, Gandhi and Islam. It would be best therefore to set out the premises of my examination of Gandhi, given the diverse narratives that have been constructed since his assassination in 1948. Primarily, and as a main contention, I do not believe Gandhi to be essentially a political figure as we understand that term today. Furthermore, he never held a political post nor was he ever elected to one. This is not the same as saying that Gandhi did not engage in politics, which he naturally did. -

Gandhi: Sources and Influences. a Curriculum Guide. Fulbright-Hays Summer Seminars Abroad, 1997 (India)

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 421 419 SO 029 067 AUTHOR Ragan, Paul TITLE Gandhi: Sources and Influences. A CurriculumGuide. Fulbright-Hays SummerSeminars Abroad, SPONS AGENCY United States 1997 (India). Educational Foundationin India. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 28p.; For other curriculum projectreports by 1997 seminar participants, see SO029 068-086. Seminar Her Ethos." title: "India and PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom EDRS PRICE - Teacher (052) MF01/PCO2 PlusPostage. DESCRIPTORS Asian Studies;Civil Disobedience; Culture; Ethnic Cultural Awareness; Groups; ForeignCountries; High Schools; *Indians; Instructional Materials;Interdisciplinary Approach; NonWestern Civilization; Social Studies;*World History; *WorldLiterature IDENTIFIERS Dalai Lama; *Gandhi (Mahatma); *India;King (Martin Luther Jr); Thoreau (HenryDavid) ABSTRACT This unit isintended for secondary literature, Asian students in American history, U.S. history,or a world cultures emphasis is placedon the literary class. Special David Thoreau, contributions of fourindividuals: Henry Mahatma Gandhi,Martin Luther King, The sections Jr., and the DalaiLama. appear in chronologicalorder and contain strategies that objectives and are designed tovary the materials the daily activities. students use in their Study questionsand suggested included. Background evaluation toolsare also is included inthe head notes of primary and secondary each section with sources listed in each is designed for section's bibliography.The unit four weeks, butcan be adapted to fit classroom needs. (EH) ******************************************************************************** -

Role of Gandhi As a Communicator

International Journal of Engineering and Technical Research (IJETR) ISSN: 2321-0869 (O) 2454-4698 (P) Volume-7, Issue-12, December 2017 Role of Gandhi as a Communicator Ms Jamna Mishra, Sonalee Nargunde Abstract– Although Gandhi might appear to be a some specific instance there has been a considerable degree of well-studied subject, there are indeed aspects of this subject that sharing, no matter who the —sharers“ are. At another level await serious scholarly attention. In our view, Gandhi as a Gandhi interacted with a very different part of the population, communicator is one such. It is generally held that Gandhi was a namely, the educated and the sophisticated, through what he great communicator and it has often been observed that Gandhi‘s success as a communicator was due to the various wrote and said. Language here becomes very important, being strategies that he had insightfully designed to communicate with the main resource of communication. Even a cursory look at the people of India, but this is perhaps only part of the his writing reveals the sincerity and the genuineness of his explanation. Besides, one might argue that those strategies concerns because of which his style had a certain character: it worked primarily because it was Gandhi who used them. The was simple, direct and clear. Consider these examples: language and the style of Gandhi and his use of the verbal and (1) Hinduism has sinned in giving sanction to untouchability non-verbal resources for communicative purposes await careful (Young India, April 24, 1921). study. To understand his effectiveness as a communicator one (2) We glibly charge Englishmen with insolence and might also consider studying his ideas and thoughts, although haughtiness.