Gandhi ´ Islam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi Warrior of Non-Violence P

SATYAGRAHA IN ACTION Indians who had spent nearly all their lives in South Africi Gandhi was able to get assistance for them from South India an appeal was made to the Supreme Court and the deportation system was ruled illegal. Meantime, the satyagraha movement continued, although more slowly as a result of government prosecution of the Indians and the animosity of white people to whom Indian merchants owed money. They demanded immediate payment of the entire sum due. The Indians could not, of course, meet their demands. Freed from jail once again in 1909, Gandhi decided that he must go to England to get more help for the Indians in Africa. He hoped to see English leaders and to place the problems before them, but the visit did little beyond acquainting those leaders with the difficulties Indians faced in Africa. In his nearly half year in Britain Gandhi himself, however, became a little more aware of India’s own position. On his way back to South Africa he wrote his first book. Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule. Written in Gujarati and later translated by himself into English, he wrote it on board the steamer Kildonan Castle. Instead of taking part in the usual shipboard life he used a packet of ship’s stationery and wrote the manuscript in less than ten days, writing with his left hand when his right tired. Hind Swaraj appeared in Indian Opinion in instalments first; the manuscript then was kept by a member of the family. Later, when its value was realized more clearly, it was reproduced in facsimile form. -

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi's Experiments with the Indian

The Social Life of Khadi: Gandhi’s Experiments with the Indian Economy, c. 1915-1965 by Leslie Hempson A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Co-Chair Professor Mrinalini Sinha, Co-Chair Associate Professor William Glover Associate Professor Matthew Hull Leslie Hempson [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5195-1605 © Leslie Hempson 2018 DEDICATION To my parents, whose love and support has accompanied me every step of the way ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ii LIST OF FIGURES iv LIST OF ACRONYMS v GLOSSARY OF KEY TERMS vi ABSTRACT vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: THE AGRO-INDUSTRIAL DIVIDE 23 CHAPTER 2: ACCOUNTING FOR BUSINESS 53 CHAPTER 3: WRITING THE ECONOMY 89 CHAPTER 4: SPINNING EMPLOYMENT 130 CONCLUSION 179 APPENDIX: WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 183 BIBLIOGRAPHY 184 iii LIST OF FIGURES FIGURE 2.1 Advertisement for a list of businesses certified by AISA 59 3.1 A set of scales with coins used as weights 117 4.1 The ambar charkha in three-part form 146 4.2 Illustration from a KVIC album showing Mother India cradling the ambar 150 charkha 4.3 Illustration from a KVIC album showing giant hand cradling the ambar charkha 151 4.4 Illustration from a KVIC album showing the ambar charkha on a pedestal with 152 a modified version of the motto of the Indian republic on the front 4.5 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing the charkha to Mohenjo Daro 158 4.6 Illustration from a KVIC album tracing -

Chapter I Introduction

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Nonviolence is the pillar of Gandhi‘s life and work. His concept of nonviolence was based on cultivating a particular philosophical outlook and was integrally associated with truth. For him, nonviolence not just meant refraining from physical violence interpersonally and nationally but refraining from the inner violence of the heart as well. It meant the practice of active love towards one‘s oppressor and enemies in the pursuit of justice, truth and peace; ―Nonviolence cannot be preached‖ he insisted, ―It has to be practiced.‖ (Dear John, 2004). Non Violence is mightier than violence. Gandhi had studied very well the basic nature of man. To him, "Man as animal is violent, but in spirit he is non-violent.‖ The moment he awakes to the spirit within, he cannot remain violent". Thus, violence is artificial to him whereas non-violence has always an edge over violence. (Gandhi, M.K., 1935). Mahatma Gandhi‘s nonviolent struggle which helped in attaining independence is the biggest example. Ahimsa (nonviolence) has been part of Indian religious tradition for centuries. According to Mahatma Gandhi the concept of nonviolence has two dimensions i.e. nonviolence in action and nonviolence in thought. It is not a negative virtue rather it is positive state of love. The underlying principle of non- violence is "hate the sin, but not the sinner." Gandhi believes that man is a part of God, and the same divine spark resides in all men. Since the same spirit resides in all men, the possibility of reforming the meanest of men cannot be ruled out. -

Domestic Violence Against Women in India: a Case Study

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN INDIA: A CASE STUDY ABSTRACT OF THE /^C THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF fioctor of $I)ilDs;opl)p •^ ^'^ IN (, POLITICAL SCIENCE BY RAHAT ZAMANI Under the Supervision of Dr. Rachana Kanshal DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE ALJGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2009 ABSTRACT Today human beings live in the so-called civilized and democratic society that is based on the principles of equality and freedom for all. It automatically results into the non-acceptance of gender discrimination in principle. Therefore, various International Human Rights norms are in place that insist on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women and advocate equal rights for women. Womens' year, women decade etc. are observed that led to the creation of mass awareness and sensitization of people about rights of women. Many steps are taken by the government in the form of various policies and programmes to promote the status of women and to realize women's rights. But despite all the efforts, the basic issue that threatens and endangers the very existence of women is the issue of domestic violence against women. John Stuart Mill put it into his book 'the subjection of women' in 1869 that, 'marriage should be thought of as a partnership of equals analogous to a business partnership and the family not a school of despotism but the real school of the virtues of freedom'. Contrary to this women who constitute about half of the world's population are the worst victim of violence and exploitation within home. -

Gandhiji on VILLAGES Selected and Compiled with an Introduction By

Gandhiji on VILLAGES Selected and Compiled with an Introduction by Divya Joshi GANDHI BOOK CENTRE Bombay Sarvodaya Mandal 299 Tardeo Road, Nana Chowk Mumbai 400007 INDIA Tel.: 2387 2061 Email: [email protected] www.mkgandhi.org MANI BHAVAN GANDHI SANGRAHALAYA MUMBAI Published with the financial assistance received from the Department of Culture, Government of India. Published with the permission of The Navajivan Trust, Ahmedabad - 380 014 First Edition 1000 copies : 2002 Set in 11/13 Point Times New Roman by Gokarn Enterprises, Mumbai Invitation Price : Rs. 30.00 Published by Meghshaym T. Ajgaonkar, Executive Secretary Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya 19, Laburnum Road, Gamdevi, Mumbai 400 007 Tel. No. 2380 5864, Fax. No. 2380 6239 E-mail: [email protected] and Printed at Mouj Printing Bureau, Mumbai 400 004. Gandhiji on VILLAGES PREFACE Gandhiji's life, ideas and work are of crucial importance to all those who want a better life for humankind. The political map of the world has changed dramatically since his time, the economic scenario has witnessed unleashing of some disturbing forces, and the social set-up has undergone a tremendous change. The importance of moral and ethical issues raised by him, however, remain central to the future of individuals and nations. Today we need him, more than before. Mani Bhavan Gandhi Sangrahalaya has been spreading information about Gandhiji's life and work. A series of booklets presenting Gandhiji's views on some important topics is planned to disseminate information as well as to stimulate questions among students, scholars, social activists and concerned citizens. We thank Government of India, Ministry of Tourism & Culture, Department of Culture, for their support. -

Kasturba Gandhi an Embodiment of Empowerment

Kasturba Gandhi An Embodiment of Empowerment Siby K. Joseph Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai 2 Kasturba Gandhi: An Embodiment…. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations to which they belong. First Published February 2020 Reprint March 2020 © Author Published by Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai Mani Bhavan, 1st Floor, 19 Laburnum Road, Gamdevi, Mumbai 400 007, MS, India. Website :https://www.gsnmumbai.org Printed at Om Laser Printers, 2324, Hudson Lines Kingsway Camp – 110 009 Siby K. Joseph 3 CONTENTS Foreword Raksha Mehta 5 Preface Siby K. Joseph 7-12 1. Early Life 13-15 2. Kastur- The Wife of Mohandas 16-24 3. In South Africa 25-29 4. Life in Beach Grove Villa 30-35 5. Reunion 36-41 6. Phoenix Settlement 42-52 7. Tolstoy Farm 53-57 8. Invalidation of Indian Marriage 58-64 9. Between Life and Death 65-72 10. Back in India 73-76 11. Champaran 77-80 12. Gandhi on Death’s door 81-85 13. Sarladevi 86-90 14. Aftermath of Non-Cooperation 91-94 15. Borsad Satyagraha and Gandhi’s Operation 95-98 16. Communal Harmony 99-101 4 Kasturba Gandhi: An Embodiment…. 17. Salt Satyagraha 102-105 18. Second Civil Disobedience Movement 106-108 19. Communal Award and Harijan Uplift 109-114 20. -

Everyman's A… B… C… of GANDHI

Everyman’s a… b… c… of GANDHI Everyman, I will go with thee, and be thy guide, in thy most need to go by thy side All quotations of Mahatma Gandhi selected from his writings are reproduced with permission of Navajivan Trust Compiled by Mahendra Meghani First Published: May 2007 Published by: Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust, Ahmedabad And Lokmilap Trust P. Box 23 (Sardarnagar), Bhavnagar 364001, Gujarat Tel. (0278)2566 402 | email: [email protected] Everyman’s a… b… c… of GANDHI Dedicated to them — Hark to the thunder, hark to the tramp — a myriad army comes! An army sprung from a hundred lands, speaking a hundred tongues! ... We come from the fields, we come from the forge, we come from the land and sea Chanting of brotherhood, chanting of freedom, dreaming the world to be -... Upton Sinclair www.mkgandhi.org Page 1 Everyman’s a… b… c… of GANDHI COMPILER'S NOTE THE COLLECTED WORKS OF MAHATMA GANDHI have been published in a hundred volumes. Numerous selections from Gandhi's writings have been compiled by editors in many countries. This process must continue till there comes along a single handy publication which, through translations in the world's major languages, might attract, inspire and move millions across the world. This little book is a humble effort in that direction. M. M. www.mkgandhi.org Page 2 Everyman’s a… b… c… of GANDHI JANUARY 1 The acts of men who have come out to serve or lead have always been misunderstood. To put up with these misrepresentations and to stick to one's guns, come what might — this is the essence of the gift of leadership. -

Unit 1 Introducing Gandhi

UNIT 1 INTRODUCING GANDHI Structure 1.1 Introduction Aims and Objectives 1.2 Gandhi’s Methodology 1.3 Synthesis of the Material and the Spiritual 1.4 Nationalism and Internationalism 1.5 Summary 1.6 Terminal Questions Suggested Readings 1.1 INTRODUCTION “The greatest fact in the story of man on earth is not his material achievement, the empires he has built and broken but the growth of his soul from age to age in its search for truth and goodness. Those who take part in this adventure of the soul secure an enduring place in the history of human culture. Time has discredited heroes as easily as it has forgotten everyone else, but the saints remain. The greatness of Gandhi is more in his holy living than in his heroic struggles, in his insistence on the creative power of the soul and its life-giving quality at a time when the destructive forces seem to be in the ascendant.” - Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan How does one introduce Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi? As a frail man, striding across the globe like a colossus? As the indomitable champion of social justice and human rights? As a ‘half-naked’ saint seeking complete identification with the poor and the deprived, silently meditating at the spinning wheel, striving to find the path of salvation for the suffering humanity? It was Winston Churchill who contemptuously described Gandhi as a ‘half-naked fakir’ and an ‘old humbug’, adding that it was “alarming and nauseating to see Mr. Gandhi, a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, striding half-naked up the steps to the Vice-Regal Palace, to parley on equal terms with the representative of the King Emperor”. -

68-77 M.K. Gandhi Through Western Lenses

68 M.K.Gandhi through Western Lenses: Romain Rolland’s Mahatma Gandhi: The Man Who Became One With the Universal Being Madhavi Nikam Volume 1 : Issue 06, October 2020 Volume Department of English, Ramchand Kimatram Talreja College, Ulhasnagar [email protected] Sambhāṣaṇ 69 Abstract: Gandhi, an Orientalist could find a sublime place in the heart and history of the Westerners with the literary initiative of a French Nobel Laureate Romain Rolland. Rolland was a French writer, art historian and mystic who bagged Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915. Rolland’s pioneering biography (in the West) on Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi published in 1924, not only made him popular overnight but also restructured the Indian figure in the minds of people. Since the publication of his biography, number of biographies on Gandhi appeared in the market from various corners of the world. Rolland himself being a pacifist was impressed with Gandhi, a man with different life style and unique modus operandi. Pacifism has greatly benefited from the biographical and historiographical revival by contribution of such great authors. Gandhi’s firm belief in the democratic and four fundamental principles of Truth (Satya), non-violence (Ahimsa), welfare of all (Sarvodaya) and peaceful protest (Satyagraha) left an indelible impact on the writer which helped him to express his resentment at imperialism in his later works. The paper would attempt to reassess Gandhi as a philosopher, and revolutionary in the context with Romain Rolland’s correspondence with Gandhi written in 1923-24. The paper will be a sincere effort to explore Rolland ‘s first but lasting impression of Gandhi who offered attractive regenerative possibilities for Volume 1 : Issue 06, October 2020 Volume Europe after the great war. -

Jagjivan Ram-Pub-4A

ADDRESSES* AT THE UNVEILING OF THE STATUE OF SHRI JAGJIVAN RAM On 25 August 1995, a statue of the former Deputy Prime Minister of India and eminent parliamentarian, Babu Jagjivan Ram was unveiled at the Entrance Hall of the Lok Sabha Lobby in Parliament House by the President of India, Dr. Shanker Dayal Sharma. The statue has been sculpted by the renowned artist, Shri Ram Sutar. The ceremony was followed by a meeting in the Central Hall which was attended by a distinguished gathering. President, Dr. Shanker Dayal Sharma, the Vice-President and Chairman, Rajya Sabha, Shri K.R. Narayanan, the Prime Minister, Shri P.V. Narasimha Rao, the Speaker, Lok Sabha, Shri Shivraj V. Patil and the daughter of Shri Jagjivan Ram, Smt. Meira Kumar addressed the gathering on the occasion. The texts of the Addresses delivered on the occasion are reproduced below. ADDRESS BY THE PRESIDENT OF INDIA, DR. SHANKER DAYAL SHARMA** Shri K.R. Narayanan, Honourable Vice-President of India, Shri P.V. Narasimha Rao, Prime Minister of India, Shri Shivraj V. Patil, Honourable Speaker, Respected Smt. Indrani Ramji, Honourable Members of the Union Council of Ministers, Leaders of the Opposition, Honourable Members of Parliament, Respected Freedom Fighters, Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen: We have gathered here today to pay our respects to Babu Jagjivan Ram, a champion of human rights and dignity and one of the great social reformers of our time. As a representative of the masses, a member of our Constituent Assembly and of successive Parliaments and Governments, Jagjivan Ramji had a profound influence in shaping contemporary India. -

BA (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year

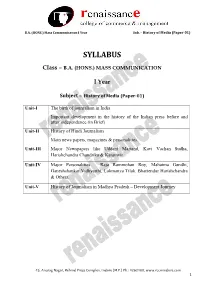

B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) SYLLABUS Class – B.A. (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year Subject – History of Media (Paper-01) Unit-I The birth of journalism in India Important development in the history of the Indian press before and after independence (in Brief) Unit-II History of Hindi Journalism Main news papers, magazines & personalities. Unit-III Major Newspapers like Uddant Martand, Kavi Vachan Sudha, Harishchandra Chandrika & Karamvir Unit-IV Major Personalities – Raja Rammohan Roy, Mahatma Gandhi, Ganeshshankar Vidhyarthi, Lokmanya Tilak, Bhartendur Harishchandra & Others. Unit-V History of Journalism in Madhya Pradesh – Development Journey 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) UNIT-I History of journalism Newspapers have always been the primary medium of journalists since 1700, with magazines added in the 18th century, radio and television in the 20th century, and the Internet in the 21st century. Early Journalism By 1400, businessmen in Italian and German cities were compiling hand written chronicles of important news events, and circulating them to their business connections. The idea of using a printing press for this material first appeared in Germany around 1600. The first gazettes appeared in German cities, notably the weekly Relation aller Fuernemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien ("Collection of all distinguished and memorable news") in Strasbourg starting in 1605. The Avisa Relation oder Zeitung was published in Wolfenbüttel from 1609, and gazettes soon were established in Frankfurt (1615), Berlin (1617) and Hamburg (1618). -

NON-VIOLENCE NEWS February 2016 Issue 2.5 ISSN: 2202-9648

NON-VIOLENCE NEWS February 2016 Issue 2.5 ISSN: 2202-9648 Nonviolence Centre Australia dedicates 30th January, Martyrs’ Day to all those Martyrs who were sacrificed for their just causes. I have nothing new to teach the world. Truth and Non-violence are as old as the hills. All I have done is to try experiments in both on as vast a scale as I could. -Mahatma Gandhi February 2016 | Non-Violence News | 1 Mahatma Gandhi’s 5 Teachings to bring about World Peace “If humanity is to progress, Gandhi is inescapable. He lived, with lies within our hearts — a force of love and thought, acted and inspired by the vision of humanity evolving tolerance for all. Throughout his life, Mahatma toward a world of peace and harmony.” - Dr. Martin Luther Gandhi fought against the power of force during King, Jr. the heyday of British rein over the world. He transformed the minds of millions, including my Have you ever dreamed about a joyful world with father, to fight against injustice with peaceful means peace and prosperity for all Mankind – a world in and non-violence. His message was as transparent which we respect and love each other despite the to his enemy as it was to his followers. He believed differences in our culture, religion and way of life? that, if we fight for the cause of humanity and greater justice, it should include even those who I often feel helpless when I see the world in turmoil, do not conform to our cause. History attests to a result of the differences between our ideals.