Let Them Eat Kale: the Misplaced Narrative of Food Access, 45 Fordham Urb

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FIC-Prop-65-Notice-Reporter.Pdf

FIC Proposition 65 Food Notice Reporter (Current as of 9/25/2021) A B C D E F G H Date Attorney Alleged Notice General Manufacturer Product of Amended/ Additional Chemical(s) 60 day Notice Link was Case /Company Concern Withdrawn Notice Detected 1 Filed Number Sprouts VeggIe RotInI; Sprouts FruIt & GraIn https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl Sprouts Farmers Cereal Bars; Sprouts 9/24/21 2021-02369 Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Market, Inc. SpInach FettucIne; 02369.pdf Sprouts StraIght Cut 2 Sweet Potato FrIes Sprouts Pasta & VeggIe https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl Sprouts Farmers 9/24/21 2021-02370 Sauce; Sprouts VeggIe Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Market, Inc. 3 Power Bowl 02370.pdf Dawn Anderson, LLC; https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02371 Sprouts Farmers OhI Wholesome Bars Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 4 Market, Inc. 02371.pdf Brad's Raw ChIps, LLC; https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02372 Sprouts Farmers Brad's Raw ChIps Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 5 Market, Inc. 02372.pdf Plant Snacks, LLC; Plant Snacks Vegan https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02373 Sprouts Farmers Cheddar Cassava Root Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 6 Market, Inc. ChIps 02373.pdf Nature's Earthly https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl ChoIce; Global JuIces Nature's Earthly ChoIce 9/24/21 2021-02374 Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- and FruIts, LLC; Great Day Beet Powder 02374.pdf 7 Walmart, Inc. Freeland Foods, LLC; Go Raw OrganIc https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl 9/24/21 2021-02375 Ralphs Grocery Sprouted Sea Salt Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- 8 Company Sunflower Seeds 02375.pdf The CarrIngton Tea https://oag.ca.gov/system/fIl CarrIngton Farms Beet 9/24/21 2021-02376 Company, LLC; Lead es/prop65/notIces/2021- Root Powder 9 Walmart, Inc. -

Wal-Mart Stores Inc at William Blair & Company, LLC Growth Stock

FINAL TRANSCRIPT WMT - Wal-Mart Stores Inc at William Blair & Company, LLC Growth Stock Conference Presentation Event Date/Time: Jun. 15. 2011 / 1:00PM GMT THOMSON REUTERS STREETEVENTS | www.streetevents.com | Contact Us ©2011 Thomson Reuters. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of Thomson Reuters content, including by framing or similar means, is prohibited without the prior written consent of Thomson Reuters. 'Thomson Reuters' and the Thomson Reuters logo are registered trademarks of Thomson Reuters and its affiliated companies. FINAL TRANSCRIPT Jun. 15. 2011 / 1:00PM, WMT - Wal-Mart Stores Inc at William Blair & Company, LLC Growth Stock Conference Presentation CONFERENCE CALL PARTICIPANTS Mark Miller William Blair - Analyst Bill Simon Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. - President & CEO Walmart U.S. PRESENTATION Mark Miller - William Blair - Analyst I think I©ll go ahead and get started so as not to cut in on management©s time. For those of you that I©ve not met, my name is Mark Miller; I follow the broadlines food, drug and e-commerce space at William Blair. I©m required to inform you that for a complete list of disclosures and potential conflicts of interest please see WilliamBlair.com. Following this presentation we will have a breakout in the Bellevue Room which, I think most of you know, is through at the restaurant. It is my pleasure this morning to introduce to you the management of Walmart. Walmart has presented now at our conference for nine of the ten years that I©ve been covering the Company. Carol, I appreciate the Company is back again this year. -

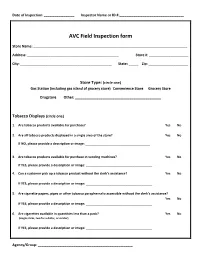

AVC Field Inspection Form

Date of Inspection: _________________ Inspector Name or ID #:____________________________________ AVC Field Inspection form Store Name: ______________________________________________________________________________________ Address: ___________________________________________________ Store #: ______________________ City: ___________________________________________________ State: _____ Zip: ______________________ Store Type: (circle one) Gas Station (including gas island of grocery store) Convenience Store Grocery Store Drugstore Other: ____________________________________________ Tobacco Displays (circle one) 1. Are tobacco products available for purchase? Yes No 2. Are all tobacco products displayed in a single area of the store? Yes No If NO, please provide a description or image: ____________________________________ 3. Are tobacco products available for purchase in vending machines? Yes No If YES, please provide a description or image: _____________________________________ 4. Can a customer pick up a tobacco product without the clerk’s assistance? Yes No If YES, please provide a description or image: _____________________________________ 5. Are cigarette papers, pipes or other tobacco paraphernalia accessible without the clerk’s assistance? Yes No If YES, please provide a description or image: _____________________________________ 6. Are cigarettes available in quantities less than a pack? Yes No (single sticks, two for a dollar, or similar) If YES, please provide a description or image: _____________________________________ Agency/Group: -

NOW ACCEPTING GROCERY COMPETITOR COUPONS and ALL MANUFACTURER COUPONS ARE NOW WORTH up to $1.00 Competitor Coupons

NOW ACCEPTING GROCERY COMPETITOR COUPONS AND ALL MANUFACTURER COUPONS ARE NOW WORTH UP TO $1.00 Competitor Coupons We will gladly accept grocery competitor coupons from Albertsons, Safeway, Basha’s, Fresh & Easy, Sunflower, Sprouts, Walmart Marketside, Walmart Neighborhood Market, Whole Foods, Target, AJ’s, Trader Joes, Food City and Ranch Market. All limits and restrictions apply. All competitor amount-off total order coupons will be redeemed after all other discounts and coupons have been applied, as long as the requirements of the coupon have been met. Only one competitor amount-off total order coupon from the same competitor may be used per shopping visit. Customers may use more than one Competitor. Example: A Fresh & Easy $5 off with a $50 required purchase plus an Albertsons $10 off with a $100 required purchase, for a total required purchase of $150, after all other discounts and coupons have been applied. • Competitor coupons will be accepted on identical items, no substitutions. • For competitor brand items use our comparable brand item. • Sorry, no rain checks. • We accept Print at Home Competitor coupons. o Competitor coupons printed from the internet may be printed in black & white. All Manufacturer Coupons Are Worth Up To $1.00! During this promotion we will make all paper manufacturer coupons up to $1.00, even those that state “Do Not Double” or “Not Subject to Doubling.” o Digital coupons downloaded onto a shopper’s VIP card are not subject to doubling Limit one manufacturer and one competitor coupon per item. Coupons Under $1: We will make up to three of the same coupon for like items up to $1.00. -

WALMART INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter) ______

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 ___________________________________________ FORM 10-K ___________________________________________ ☒ Annual report pursuant to section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 For the fiscal year ended January 31, 2020, or ☐ Transition report pursuant to section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Commission file number 001-6991. ___________________________________________ WALMART INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) ___________________________________________ DE 71-0415188 (State or other jurisdiction of (IRS Employer Identification No.) incorporation or organization) 702 S.W. 8th Street Bentonville, AR 72716 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: (479) 273-4000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered Common Stock, par value $0.10 per share WMT NYSE 1.900% Notes Due 2022 WMT22 NYSE 2.550% Notes Due 2026 WMT26 NYSE Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None ___________________________________________ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ý No ¨ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes ¨ No ý WorldReginfo - ddf1e3e1-b7d7-4a92-84aa-57ea0f7c6df3 Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for at least the past 90 days. -

Houchens Industries Jimmie Gipson 493 2.6E Bowling Green, Ky

SN TOP 75 SN TOP 75 2010 North American Food Retailers A=actual sales; E=estimated sales CORPORATE/ SALES IN $ BILLIONS; RANK COMPANY TOP EXECUTIVE(S) FRancHise STORes DATE FISCAL YEAR ENDS 1 Wal-Mart Stores MIKE DUKE 4,624 262.0E Bentonville, Ark. president, CEO 1/31/10 Volume total represents combined sales of Wal-Mart Supercenters, Wal-Mart discount stores, Sam’s Clubs, Neighborhood Markets and Marketside stores in the U.S. and Canada, which account for approximately 64% of total corporate sales (estimated at $409.4 billion in 2009). Wal-Mart operates 2,746 supercenters in the U.S. and 75 in Canada; 152 Neighborhood Markets and four Marketside stores in the U.S.; 803 discount stores in the U.S. and 239 in Canada; and 605 Sam’s Clubs in the U.S. (The six Sam’s Clubs in Canada closed last year, and 10 more Sam’s are scheduled to close in 2010.) 2 Kroger Co. DAVID B. DILLON 3,634 76.0E Cincinnati chairman, CEO 1/30/10 Kroger’s store base includes 2,469 supermarkets and multi-department stores; 773 convenience stores; and 392 fine jewelry stores. Sales from convenience stores account for approximately 5% of total volume, and sales from fine jewelry stores account for less than 1% of total volume. The company’s 850 supermarket fuel centers are no longer included in the store count. 3 Costco Wholesale Corp. JIM SINEGAL 527 71.4A Issaquah, Wash. president, CEO 8/30/09 Revenues at Costco include sales of $69.9 billion and membership fees of $1.5 billion. -

Feature Advertising by U.S. Supermarkets Meat and Poultry

United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Feature Advertising by U.S. Supermarkets Marketing Service Meat and Poultry Livestock, Poultry and Seed Program Independence Day 2017 Agricultural Analytics Division Advertised Prices effective through July 04, 2017 Feature Advertising by U.S. Supermarkets During Key Seasonal Marketing Events This report provides a detailed breakdown of supermarket featuring of popular meat and poultry products for the Independence Day marketing period. The Independence Day weekend marks the high watershed of the summer outdoor cooking season and is a significant demand period for a variety of meat cuts for outdoor grilling and entertaining. Advertised sale prices are shown by region, state, and supermarket banner and include brand names, prices, and any special conditions. Contents: Chicken - Regular and value packs of boneless/skinless (b/s) breasts; b/s thighs; split, bone-in breasts; wings; bone-in thighs and drumsticks; tray and bagged leg quarters; IQF breast and tenders; 8-piece fried chicken. Northeast .................................................................................................................................................................. 03 Southeast ................................................................................................................................................................. 21 Midwest ................................................................................................................................................................... -

Battle of the Titans in Phoenix, Arizona

SPECIAL REPORT Wal-Mart Pricing ReportRound XIX Battle Of The Titans In Phoenix, Arizona Wal-Mart’s trifecta — the Supercenter, Neighborhood Market and Marketside — rules the roost in Phoenix. BY JIM PREVOR ome believe that the future of American retailing well represented in the marketplace with its Fry’s division. can be glimpsed in Phoenix, AZ. Between its large Tesco, the behemoth from across the sea, also used Phoenix as senior citizen population and large Hispanic popula- a launching grounds for its Fresh & Easy small store concept. tion, one can argue that this is what retailing in In addition to these national chain concepts, we included in America will look like in not all that many years. our comparison a strong independent: Basha’s Supermarkets. SSo we traveled down to Phoenix for the 19th iteration of our What can we surmise from the outcome of our produce pric- Wal-Mart Pricing Study, seeking not just our usual quest — the ing competition among this array of retailers in Phoenix? low price champion in one city — but also seeking enlighten- Many things to be sure, but as a first order, this: If Phoenix ment as to what the future might bring for retailing all across is the future of American retailing, and if price for a cus- the country. tomer walking in off the street is the key variable, then One thing is certain: Phoenix is, in fact, a place where a bat- the future belongs to Wal-Mart. tle of the Titans is playing out. It is the only market in America Not only was the Wal-Mart Supercenter the low price leader where one has a representation of three separate Wal-Mart con- in Phoenix, but the Wal-Mart Neighborhood Market concept cepts — the Wal-Mart Supercenter, the Wal-Mart Neighborhood came in number two, and Wal-Mart’s Marketside concept came Market and the new, small-store Wal-Mart concept known as in third! A trifecta! It hardly seems possible. -

Passover Approved Products Items Listed in This Section Are Certified for Year-Round Use and Are Kosher for Passover Even Without Special Passover Certification

PASSOVER CONSUMER GUIDE INDEX PASSOVER APPROVED PRODUCTS ITEMS LISTED IN THIS SECTION ARE CERTIFIED FOR YEAR-ROUND USE AND ARE KOSHER FOR PASSOVER EVEN WITHOUT SPECIAL PASSOVER CERTIFICATION. AVOCADO OIL ..........................................66 DISH DETERGENTS ......................... 68 PAPER, PLASTIC, WRAPS, FOIL & CANDLES ................................. 72 BAKING SODA ......................................... 66 EGG PRODUCTS .................................. 68 PERSONAL & ORAL HYGIENE 74 BEVERAGES ................................................ 66 FISH RAW ....................................................... 68 RAISINS Not oil-treated only ............ 74 CLEANERS & DETERGENTS 66 JUICES AND JUICE CONCENTRATE Unsweetened 68 SALT Non-iodized only ........................... 74 COCOA POWDER ............................... 66 ................................................................. MEAT & POULTRY ............................. 68 SUGAR 74 COCONUT OIL: Virgin only ......... 66 Brown • White Granulated In Original Manufacturer Packaging ............ 68 ................................................... Broiled Livers (Excluding Ground) ................. 68 COFFEE 66-67 TEA BAGS ....................................................... 74 • Ground or Whole Bean Unflavored • Unflavored, Decaffeinated NUTS ........................................................... 68-69 Not Decaffeinated ............................................... 66 Raw: Whole, Pieces and Nut Meal • Unflavored, Not Decaffeinated & Not Herbal • Ground -

Retail Address City State

RETAIL ADDRESS CITY STATE MILITARY:AAFES ELMEN MAIN STORE BLDG 5800 WESTOVER AVE ELMENDORF AFB AK EIELSON SHOPPING CENTER 451 BROADWAY EIELSON AFB AK MILITARY: ELMENDORF JMM SHOPPETTE 3827 WESTOVER AVE ELMENDORF AFB AK CLEAR AFB PACKAGE STORE BUILDING 201 CLEAR AFB CLEAR AK MILITARY:AAFES PKG FT RICH BLDG 5 FT RICHARDSON AK FT GREELY PX BLDG #602 FORT GREELY AK BROWN JUG #278 - FBK 559 HAROLD BENTLEY AVE FAIRBANKS AK BROWN JUG #242 - ANCH WH 4140 OLD SEWARD HWY ANCHORAGE AK BROWN JUG #267 - WASILLA WH 2521 E MNT VILLAGE DR WASILLA AK BROWN JUG #235 - EAGLE RIVER 11221 OLD GLENN HWY EAGLE RIVER AK BROWN JUG #264 - 1106 N MULDOON 1106 N MULDOON RD STE 110 ANCHORAGE AK BROWN JUG #263 - VICTOR 2203 W DIMOND BLVD ANCHORAGE AK BROWN JUG #276 - EAST N LIGHTS 5400 E NORTHERN LIGHTS BLVD ANCHORAGE AK BROWN JUG #226 - INDEPENDENCE PARK 2121 ABBOTT RD ANCHORAGE AK BROWN JUG #212 - OLD SEWARD S 9200 OLD SEWARD HWY ANCHORAGE AK BROWN JUG #250 - DOWNTOWN 930 W 5TH AVE ANCHORAGE AK BROWN JUG #251 - MULDOON WHALER 171 MULDOON RD ANCHORAGE AK BROWN JUG #255 - S BRAGAW 131 S BRAGAW ST ANCHORAGE AK BROWN JUG #275 - SPENARD 3904 SPENARD RD ANCHORAGE AK BROWN JUG #232 - MT VIEW 119 KLEVIN ST ANCHORAGE AK BROWN JUG #254 - 509 PARKS HWY 509 W PARKS HWY WASILLA AK BROWN JUG #221 - MINNESOTA 3727 SPENARD RD ANCHORAGE AK BROWN JUG #223 - FIREWEED 525 W FIREWEED LN ANCHORAGE AK BROWN JUG #213 - TUDOR 3561 TUDOR RD ANCHORAGE AK BROWN JUG #234 - BRAGAW 1555 S BRAGAW ANCHORAGE AK FRED MEYER #653 - WASILLA 1501 PARKS HWY WASILLA AK FRED MEYER #224 - STEESE HWY 930 -

2013 Global Responsibility Report

Use to arrange cover images 2013 Global Responsibility Report esponsibility to he R Lea l T d g l G rin iv u in ct g fa l u S n u a s M ta l i n s a d b o i li o t F y I r n e i d h e t l x a l e J H o l b s s a n n a d r e O t p e V p o l r t y u t i n s i r t e y v i l D W e t o a m i c e o n s ’ s s A E m l p f o e i w l e e R r m r e e g n n t u l H R l e n y e g w r e a n b E l e 2 Message from Mike Duke Contents 6 How Walmart made a difference in 2012 18 Progress at-a-glance Social responsibility Local responsibility 22 Ethical sourcing 96 Our company 40 Global audit results 98 Africa 42 Global women’s 102 Argentina economic empowerment 106 Brazil 44 Hunger relief 110 Canada 46 Healthier food 114 Central America 48 Giving 118 Chile 49 Disaster relief 122 China 126 India Environmental responsibility 130 Japan 52 Sustainability 360 134 Mexico 53 Sustainable Value Networks 138 United Kingdom 54 Renewable energy 142 U.S. – Walmart 56 Greenhouse gas (GHG) 148 U.S. – Sam’s Club 58 Energy efficiency and buildings 59 Energy: Fleet Our progress 60 Waste 152 2012 commitments and progress 62 Sustainability Index 162 Global Reporting Initiatiave index 64 Sustainable agriculture 68 Supply chain GHG Company responsibility 72 Stakeholder engagement 74 Governance 75 Public policy 76 Ethics and integrity 78 Compliance 82 Safety 84 Diversity 87 Talent development 89 Recruiting 90 Benefits and compensation 92 Associate engagement 93 My Sustainability Plan About this report The scope and boundaries of the 2013 Walmart Global Responsibility Report encompass Company responsibility | 70 our corporate social, environmental and company responsibility efforts, while also providing snapshots into each of our individual markets around the globe. -

Peach Recall Expands Due to Potential Health Hazard

Peach Recall Expands Due to Potential Health Hazard August 24, 2020 - The Kane County Health Department is advising that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and state and local partners, is investigating an ongoing multistate outbreak of Salmonella Enteritidis infections potentially linked to peaches packed or supplied by Prima Wawona or Wawona Packing Company. Retailers that received recall product from Prima Wawona or Wawona Packing Company include, but are not limited to: ALDI, Target, Walmart, Wegmans and Kroger, including the following affiliated retailers: Jay-C, King Soopers, City Market, Fry's, Ralphs, Food 4 Less, Foods Co. and Smiths. The bulk/loose peaches supplied by Prima Wawona are sold in grocery stores in a variety of formats, typically bins where consumers may select their own fruit and may have the following stickers with PLU numbers on them: 4037, 4038, 4044, 4401, 94037, 94038, 94044, 94401. Please note that not all peaches with these PLU codes are supplied by Prima Wawona. If you are unsure of the brand or variety of your loose peaches, you can contact your retailer or supplier, or throw them out. The bagged peaches were distributed and sold in supermarkets with the following product codes: • Wawona Peaches – 033383322001 • Wawona Organic Peaches – 849315000400 • Prima® Peaches – 766342325903 • Organic Marketside Peaches – 849315000400 • Kroger Peaches – 011110181749 • Wegmans Peaches – 077890490488 For bagged peaches, the product codes may be found at the bottom of each package. All affected peaches may be found in stores nationwide. (more) Peach Recall Expands Due to Potential Health Hazard – page 2 CDC reports that epidemiologic evidence indicates that peaches are the likely source of this outbreak.