Public Libraries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transportation on the Minneapolis Riverfront

RAPIDS, REINS, RAILS: TRANSPORTATION ON THE MINNEAPOLIS RIVERFRONT Mississippi River near Stone Arch Bridge, July 1, 1925 Minnesota Historical Society Collections Prepared by Prepared for The Saint Anthony Falls Marjorie Pearson, Ph.D. Heritage Board Principal Investigator Minnesota Historical Society Penny A. Petersen 704 South Second Street Researcher Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 Hess, Roise and Company 100 North First Street Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 May 2009 612-338-1987 Table of Contents PROJECT BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................. 1 RAPID, REINS, RAILS: A SUMMARY OF RIVERFRONT TRANSPORTATION ......................................... 3 THE RAPIDS: WATER TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS .............................................. 8 THE REINS: ANIMAL-POWERED TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ............................ 25 THE RAILS: RAILROADS BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ..................................................................... 42 The Early Period of Railroads—1850 to 1880 ......................................................................... 42 The First Railroad: the Saint Paul and Pacific ...................................................................... 44 Minnesota Central, later the Chicago, Milwaukee and Saint Paul Railroad (CM and StP), also called The Milwaukee Road .......................................................................................... 55 Minneapolis and Saint Louis Railway ................................................................................. -

Hennepin County Library Community Resource Guide

Navigation Guide July 2020 This resource was created by Summer Reads VISTA members. Summer Reads is an AmeriCorps VISTA national service program of Literacy Minnesota. For 8 weeks over the summer, Summer Reads VISTA members volunteer full-time as children’s/youth literacy mentors in schools, libraries and out-of-school-time programs across Minnesota. They bring literacy to life for low-income students through a variety of activities – one-on-one tutoring, creative enrichment activities like using arts and drama to explore language or practicing vocabulary and comprehension in science and other subjects. They also connect students and parents/caregivers to community resources through wrap-around basic needs support. At the same time, the VISTA members build their own leadership, explore career paths, pay for college and become lifelong advocates for the communities they serve due to the power of their experience. www.literacymn.org/summerreads 2 The Library is MORE than just books! The library has so much to offer! Books, events, classes, activities, and information assistance are available online, at the library, and in the community. And best of all? Nearly all these services are free and open to all. • 41 library locations, with more than 70 additional outreach sites • Residents check-out nearly 16 million items each year • 64 percent of Hennepin County residents have a library card • Librarians answer 1.4 million reference questions each year • 40,000 patrons participate Hennepin County Library in summer reading program Fast Facts How to Get a Library Card Library cards are free and give you access to everything the library has to offer. -

Libraries and Innovation: 21 St Century Themes

Libraries and innovation: 21st century themes Dr. Jerry Stein Founder and Director | Learning Dreams School of Social Work |University of Minnesota S.E. Advisory Committee Meeting #2 Hennepin County, Minneapolis Central Library Minneapolis, Minnesota September 26, 2014 Table of contents 1. Lending 2. Makerspaces 3. Libraries as art incubators 4. Mobile libraries 5. Teens 6. Spaces, community & democracy 7. The shifting roles of librarians 8. Library collaborations and partnerships Lending Lending, a traditional library function, has grown to allow libraries to fit into their own communities by being able to offer unique services targeted toward the needs and desires of the specific location. If, in addition to book lending, a library also lends unusual items, objects or services - such as musical instruments - over time, the branch often follows through with additional support like music teachers, concerts, etc. Here are some examples: Tools Berkeley's Tool Lending Library Berkeley, California Seeds Seed lending library Richmond Public Library | Richmond, California Musical instruments Ukulele lending library Musical instruments Portland Public Library Lopez Island Library Portland, ME Lopez Island, WA Internet New York, New York Humans Ottawa Public Library Ontario, Canada Cake pans New Gloucester Public Library New Gloucester, Maine Outdoor equipment Topsham Public Library Topsham, Maine Outdoor exploration York Public Library | York, Maine Makerspaces The nature of knowledge is changing. With technology becoming increasingly accessible, more and more people are transitioning from simple consumers of information to creators and inventors of knowledge. Anyone with a smart phone has, in their pocket, a sound studio, a video production system, an artist's palette and more. -

Minneapolis Public Library Information Center Annual

MINNEAPOLIS PUBLIC LIBRARY & INFORMATION CENTER ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR ANNUAL REPORTS OF DEPARTMENTS AND COMMUNITY LIBRARIES ATHENAEUM 1981 Volume I CONTENTS VOLUME I ADMINISTRATION SPECIAL SERVICES CENTRAL LIBRARY SERVICES ATHENAEUM 1981 Director of the Library • . • . • • • • . • . • . • • • . • • • • . • . 1 Associate Director • • • . • • • • . • . • • . • . • . • • . • . • . • • . • . • . • 7 Accounting Office . • • . • . • • • . • • • . • . • . • • 11 Building Maintenance . • . • • • • . • . • • . • • • • • . • • • • • . • . • • . • • 12 Personnel . 17 Special Services . • • . • • . • . • • . • • . • . • • • • • • . • . • • • . • • • 22 Community Outreach . • • . • . • . • . • • • . • . • . • • . • . • • 25 Environmental Conservation Library.................. 30 INF'OPJ1 . • . • • • . • . • . • • . • . • . • . 3 4 Interlibrary Loan . • . • . • • . • . • . • . • . • . 35 Minneapolis: Portrait of a Lifestyle............... 39 Municipal Information Library . • . • . • . 41 Publicity Off ice . • . • . 45 Chief of Central Library Services •..•..•..•..•............ 48 Machine Assisted Reference Service Advisory Committee •. 54 Central Library Book Selection Librarian............... 59 Subject Departments Art, Music, Films . • . • . • . • . 64 Business and Science . • . • • . • • • • . • . • • • • • 75 Children's Room • . • • . • • . • . • • • . • . • . • • • . • . 86 Government Documents ....•...•...•. , • • • • . • . • . • 93 History and Travel • . • • . • . • . • . 98 Minneapolis History Collection . • • • • . • . • . • 106 Literature -

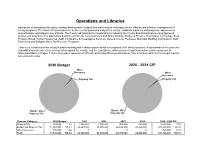

Capital Budget – Operations and Libraries

Operations and Libraries Operations encompasses the policy making, administrative support and staff services necessary for the efficient and effective management of county programs. The Board of Commissioners, as the elected governing body of the county, establishes policies and programs, approves the annual budget, and appoints key officials. The County Administrator is responsible for advising the County Board and implementing approved policies and programs. The Operations departments include Commissioners and Administration, Budget & Finance, Information Technology, Real Property Group, Human Resources, Audit Compliance & Investigative Services, General County Purposes, Municipal Building Commission, Debt Retirement and Ballpark Sales Tax Revenue Programs. Libraries is comprised of the county's award winning public library system which is comprised of 41 library locations, a substantial on-line presence and additional outreach services located throughout the county, and the Law Library, which provides legal information services pursuant to Minnesota Statues Chapter 134A to the judges, government officials, practicing attorneys and citizens from a location within the Hennepin County Government Center. 2020 Budget 2020 - 2024 CIP Other Revenues Other Revenues Property Tax Property Tax #DIV/0! Bonds: GO Bonds: GO Property Tax Property Tax Revenue Category 2020 Budget 2021 2022 2023 2024 2020 - 2024 CIP Property Tax 864,000 1.2% 1,565,000 1,050,000 800,000 800,000 5,079,000 1.5% Bonds: GO Property Tax 71,968,000 97.8% 86,629,000 95,570,000 -

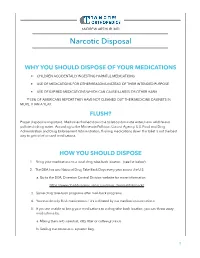

Narcotic Disposal

ANDREW ARTHUR, MD Narcotic Disposal WHY YOU SHOULD DISPOSE OF YOUR MEDICATIONS • CHILDREN ACCIDENTALLY INGESTING HARMFUL MEDICATIONS • USE OF MEDICATIONS FOR OTHER REASONS INSTEAD OF THEIR INTENDED PURPOSE • USE OF EXPIRED MEDICATIONS WHICH CAN CAUSE ILLNESS OR OTHER HARM **33% OF AMERICANS REPORT THEY HAVE NOT CLEANED OUT THEIR MEDICINE CABINETS IN MORE THAN A YEAR. FLUSH? Proper disposal is important. Medicines flushed down the toilet contaminate water, harm wildlife and pollute drinking water. According to the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, U.S. Food and Drug Administration and Drug Enforcement Administration, flushing medications down the toilet is not the best way to get rid of unused medications. HOW YOU SHOULD DISPOSE 1. Bring your medications to a local drug take-back location. (see list below) 2. The DEA has two National Drug Take Back Days every year across the U.S. a. Go to the DEA, Diversion Control Division website for more information https://www.deaddiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_disposal/takeback/ 3. Some drug take-back programs offer mail-back programs 4. You should only flush medications if it’s indicated by the medication instructions 5. If you are unable to bring your medications to a drug take-back location, you can throw away medications by: a. Mixing them with sawdust, kitty litter or coffee grounds. b. Sealing the contents in a plastic bag. !1 LOCATIONS TO DISPOSE Brooklyn Center Minneapolis Police Department Hennepin County District Court Brookdale 1st precinct 6125 Shingle Creek Pkwy, Brooklyn Center, MN 19 N 4th St., Minneapolis, MN Hours: Mon-Thurs 9 a.m. - 9 p.m. -

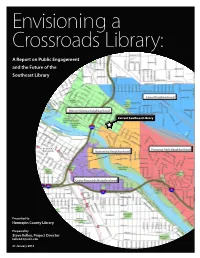

Envisioning a Crossroads Library

Envisioning a Crossroads Library: A Report on Public Engagement and the Future of the Southeast Library Como Neighborhood Marcy-Holmes Neighborhood Current Southeast Library Downtown Prospect Park Neighborhood Minneapolis University Neighborhood Cedar Riverside Neighborhood Presented to Hennepin County Library Prepared by Steve Kelley, Project Director [email protected] 21 January 2015 Acknowledgements Project Collaborators Meredith Brandon – Graduate research assistant and report author Steve Kelley – Senior Fellow, project director Bryan Lopez – Graduate research assistant and report author Dr. Jerry Stein – Project advisor Ange Wang – Design methods consultant Sandra Wolfe-Wood – Design methods consultant Community Contributors Najat Ajaram - Teacher at Minneapple International Montessori School Sandy Brick - Local artist and SE Library art curator Sara Dotty - Literary Specialist at Marcy Open School Rev. Douglas Donley - University Baptist Church Pastor Cassie Hartnett – Coordinator of Trinity Lutheran Homework Help Eric Heideman – Librarian at Southeast Library Paul Jaeger – Recreation Supervisor at Van Cleve Recreation Center David Lenander – Head of the Rivendell Group Gail Linnerson – Librarian with Hennepin County Libraries Wendy Lougee - Director of UMN Libraries Jason McLean – Owner and manager of Loring Pasta Bar and Varsity Theater Marji Miller - Executive Director SE Seniors Mike Mulrooney – Owner of Blarney’s Pub in Dinkytown Huy Nguyen - Luxton Recreation Center Director James Ruiz – Support staff member at Southeast Library -

Minneapolis Public Library Information Center Annual

MINNEAPOLIS PUBLIC LIBRARY & INFORMATION CENTER ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DIRECTOR ANNUAL REPORTS OF DEPARTMENTS AND COMMUNITY LIBRARIES ATHENAEUM 1985 Volume I CONTENTS VOLUME I ADMINISTRATION CENTRAL LIBRARY SERVICES ATHENAEUM 1985 Director of the Library .•••.•.....•.......•..••.••..... 1 Associate Director . • . • . • • . • • . • . • . • • . • • • • • . • • • 5 Accounting Office • . • • . • . • . • . 8 Building Staff • . • • . • . • . • . 9 INFORM . • . • . • • . • . • . • • . • . • . • . • • • • . • 15 Interlibrary Loan • . • • • . • . • • . • • . • . • • • • . • • . • • . • 20 Personnel Off ice . • • • • • . • . • . • . • • . • • • • • . • • . • . • 24 Public Relations Office ..•..••.••....•..•...•.•..... 36 Chief of Central Library Services ..••••...•..•..••..•.. 41 MARS Advisory Committee .•.......•...............•... 45 Central Library Book Selection Office ••............. 50 Subject Departments Art, Music, Films . 58 Business and Economics .•.•..••.•......•...••.••.• 67 Children' s Room • . • . • • . • • . • . • . • . • . • • . • . • • • . • . 7 7 Government Documents • . • . • • . • • • . • • . • . 85 Municipal Information Library .•••.•..........• 91 History and Travel . • . • . • . • . • • . • . • . • . • 94 Minneapolis History Collection .............•.. 102 Literature . • . • • . • . • . • . • . 106 Sociology . • . • . • . • . 113 Technology and Science . • . • • . • . • . • . • . • . • 120 Shelving . • • . • . • . • . • • • . • . • . • . • . • • . 136 Chief of Technical Services ...........•................ 139 Acquisitions/Electronic -

Mission Statement Hennepin County Library's Mission Is to Nourish

Mission Statement Hennepin County Library’s mission is to nourish minds, transform lives and build community together. Cargill Hall Exhibits & Programming Proposal Form Preparation of materials for exhibit and display purposes is the responsibility of the exhibitor and must meet the standards of Hennepin County Library. Please review the Information for Exhibitors before submitting your application. Applications will be reviewed biannually in January and July for exhibition the following year. General Information Contact Person: Organization: Address: City: State: Phone Number: Email: Website of Organization or Exhibiting Artists: 1. Exhibit Content Please attach an exhibit proposal addressing the following as well as any additional information you would like us to know about your exhibit. Limit proposal to one page. • Exhibit Title • Describe the exhibit. What do you want to show and why? Please include the following: o Why do you want to exhibit at the Minneapolis Central Library? o Who are the target audiences? o What types of objects will be on display (i.e. paintings, prints, sculpture, photographs, artifacts, etc.) 2. Sample Images Please include up to 5 jpg images (72-300 dpi) of the work or material that will be on display. Links to online images or videos of the work or material may also be included. For art exhibits where work is not yet complete, please provide sample images of artist’s other work. 3. Proposed Dates/Timing Exhibits run for two months including installation and de-installation. Exhibits are scheduled about one year in advance. When is the exhibition available? (Select all availabilities and indicate year.) ☐ February/March ☐ August/September ☐ April/May ☐ October/November ☐ June/July ☐ December/January / 4. -

Library Board Agenda

THE PUBLIC IS WELCOME AT ALL LIBRARY BOARD MEETINGS May 8, 2019, 5-7:00 p.m. Ridgedale Library | Robert H. Rohlf Meeting Room | 12601 Ridgedale Dr. | Minnetonka, MN Library Board Agenda 1. CALL TO ORDER 8. LIBRARY BOARD DIALOGUE, 2020 A. New Member Introduction OPERATING BUDGET OUTCOMES A. Disparity Reduction, Janet Mills B. Library Budget Overview, Nancy 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA* Palmer C. Library Budget Dialogue, Nick 3. CONSENT* Andrews A. Approval of Minutes of February 27, 2019 B. Acceptance of Donations 9. LIBRARY BOARD POLICIES A. 2019 Policy Review – Review Drafts* 4. PUBLIC COMMENT I. Collection Development and Management 5. COMMENDATION* II. Freedom to Read A. Caitlin Cahill, Library Board III. Freedom to View IV. Lending 6. PRESIDENT’S REPORT V. Policy Review Policy A. Chuck Salter, Hennepin County Attorney 10. DIRECTOR’S REPORT B. Announcements A. Library, County, and Community C. Executive Committee Report Updates D. 2019 Meeting Locations* E. Director Selection Process 11. COMMITTEE REPORTS Committee Report A. Friends of Hennepin County Library, Erin F. Computers in Libraries Conference Vrieze Daniels Report, Chris Damsgard and Jonathan Gaw 12. UNFINISHED BUSINESS 7. ELECTION OF OFFICERS 13. NEW BUSINESS A. Chris Damsgard, Nominating Committee Chair* 14. ADJOURN* Denotes board action item. THE PUBLIC IS WELCOME AT ALL LIBRARY BOARD MEETINGS HENNEPIN COUNTY LIBRARY BOARD MEETING Meeting Minutes The Hennepin County Library Board met Wednesday, February 27, 2019, Ridgedale Library, Robert H. Rohlf meeting room. ATTENDEES Library -

Public Library Services and Facilities in Minneapolis

CITIZENS LEAGUE REPORT No. 175 Public Library Services & Facilities City of Minneapolis March 1965 Citizens League 545 Mobil Oil Building Minneapolis, Minnesota 55402 CONCLUSIONS AND RECO1~DBTIOnTSON THE DIRECTION AND F'UTUXE OF PUBLIC LCBRARY SZRVICE AND FACILITIES IN HEWEPIN CO~TYAND MINN~APOLCS Summary Statement Two compelling conclusions have energed from the Citizens LeagueQs11-month study of City and County libraries -- I. That the Legislature this session should pro- vide for a City-County Library Board with representation from suburban and rural Hennepin County equal to that from the City, and, 11. That closer cooperation be- tween the City and County library systems, continuing to operate as two systems but under a common board, is vitally needed for the development of a satisfactory plan for new library construction and for efficient operations of the two systems through standardization of operating practices and procedures. I, Growth and development have brought the suburbs to the point of crucial decis- ions on the future of their libraries -- mat kind of library service should they have? Wnat size and type facilities and how many libraries should they have? Be- cause of the fundamental and far-reaching importance of these imminent decisions, we believe the suburbs mst have a major voice in determining the librariesq future in Hennepin County. Currently, the Hennepin County Library system is governed by the Minneapolis Library Board-under contract with" the ~enke~in~ount~-~oard. we suggest thk crea- tion of a City-County Library Board with equal city and suburban representation. Although we see much potential merit in a county or areawide library system,we are not suggesting a merged or consolidated library system at this time for the fol- lowing reasons : A. -

Capital Budget – Libraries and Operations

Operations and Libraries Operations encompasses the policy making, administrative support and staff services necessary for the efficient and effective management of county programs. The Board of Commissioners, as the elected governing body of the county, establishes policies and programs, approves the annual budget, and appoints key officials. The County Administrator is responsible for advising the County Board and implementing approved policies and programs. The Operations departments include Commissioners and Administration, Budget & Finance, Information Technology, Real Property Group, Human Resources, Audit Compliance & Investigative Services, General County Purposes, Municipal Building Commission, Debt Retirement and Ballpark Sales Tax Revenue Programs. Libraries is comprised of the county's award winning public library system which is comprised of 41 library locations, a substantial on-line presence and additional outreach services located throughout the county, and the Law Library, which provides legal information services pursuant to Minnesota Statues Chapter 134A to the judges, government officials, practicing attorneys and citizens from a location within the Hennepin County Government Center. 2018 2018 - 2022 CIP Other Other Revenues Revenues Property Tax Property Tax County County Bonds Bonds Revenue Category 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2018 - 2022 CIP Property Tax 900,000 0.7% 1,450,000 1,450,000 1,450,000 1,150,000 6,400,000 2.0% County Bonds 122,913,000 98.8% 75,632,000 56,868,000 44,521,000 17,922,000 317,856,000 97.2% Other