April 2018 Newsletter [PDF 2 MB]Biodiversity Survey with The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Additional Information

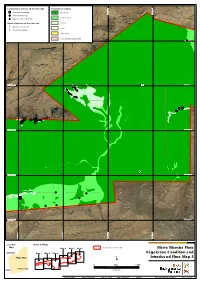

Current Survey Introduced Flora Records Vegetation Condition *Acetosa vesicaria Excellent 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 536,000 mE 536,000 537,000 mE 537,000 534,000 mE 534,000 mE 535,000 534,000 mE 534,000 -

Conservation Management Zones of Australia

Conservation Management Zones of Australia Mitchell Grasslands Prepared by the Department of the Environment Acknowledgements This project and its associated products are the result of collaboration between the Department of the Environment’s Biodiversity Conservation Division and the Environmental Resources Information Network (ERIN). Invaluable input, advice and support were provided by staff and leading researchers from across the Department of Environment (DotE), Department of Agriculture (DoA), the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and the academic community. We would particularly like to thank staff within the Wildlife, Heritage and Marine Division, Parks Australia and the Environment Assessment and Compliance Division of DotE; Nyree Stenekes and Robert Kancans (DoA), Sue McIntyre (CSIRO), Richard Hobbs (University of Western Australia), Michael Hutchinson (ANU); David Lindenmayer and Emma Burns (ANU); and Gilly Llewellyn, Martin Taylor and other staff from the World Wildlife Fund for their generosity and advice. Special thanks to CSIRO researchers Kristen Williams and Simon Ferrier whose modelling of biodiversity patterns underpinned identification of the Conservation Management Zones of Australia. Image Credits Front Cover: Lawn Hill National Park – Peter Lik Page 4: Kowaris (Dasyuroides byrnei) – Leong Lim Page 10: Oriental Pratincole (Glareola maldivarum) – JJ Harrison Page 16: Australian Fossil Mammal Sites (Riversleigh) – World Heritage Listed site – Colin Totterdell Page 18: Mitchell Grasslands -

Summary of Plots in the Lake Eyre Basin

S ummary of Plots in the Lake Eyre Basin 2010 - 2016 Cravens Peak Reserve, QLD Acknowledgments TERN AusPlots Rangelands gratefully acknowledges the staff of the numerous properties both public and private that have helped with the work and allowed access to their land. AusPlots Rangelands also acknowledges the staff from the 4 state and territory governments who have provided assistance on the project. Thanks also to the many volunteers who helped to collect, curate and process the data and samples. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Accessing the Data ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 Point intercept data ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Plant collections ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Leaf tissue samples ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Site description information .............................................................................................................................. 3 Structural summary .......................................................................................................................................... -

DRAFT 25/10/90; Plant List Updated Oct. 1992; Notes Added June 2021

DRAFT 25/10/90; plant list updated Oct. 1992; notes added June 2021. PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE CONSERVATION VALUES OF OPEN COUNTRY PADDOCK, BOOLARDY STATION Allan H. Burbidge and J.K. Rolfe INTRODUCTION Boolardy Station is situated about 150 km north of Yalgoo and 140 km west-north-west of Cue, in the Shire of Murchison, Western Australia. Open Country Paddock (about 16 000 ha) is in the south-east corner of the station, at 27o05'S, 116o50'E. The most prominent named feature is Coolamooka Hill, near the eastern boundary of the paddock. There are no conservation reserves in this region, although there are some small reserves set aside for various other purposes. Previous biological data for the station consist of broad scale vegetation mapping and land system mapping. Beard (1976) mapped the entire Murchison region at 1: 1 000 000. The Open Country Paddock area was mapped as supporting mulga woodlands and shrublands. More detailed mapping of land system units for rangeland assessment purposes has been carried out more recently at a scale of 1: 40 000 (Payne and Curry in prep.). Seven land systems were identified in open Country Paddock (Fig. 1). Apart from these studies, no detailed biological survey work appears to have been done in the area. Open Country Paddock has been only lightly grazed by domestic stock because of the presence of Kite-leaf Poison (Gastrolobium laytonii) and a lack of fresh water. Because of this and the generally good condition of the paddock and presence of a wide range of plant species, P.J. -

Volume 5 Pt 3

Conservation Science W. Aust. 7 (1) : 153–178 (2008) Flora and Vegetation of the banded iron formations of the Yilgarn Craton: the Weld Range ADRIENNE S MARKEY AND STEVEN J DILLON Science Division, Department of Environment and Conservation, Wildlife Research Centre, PO Box 51, Wanneroo WA 6946. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT A survey of the flora and floristic communities of the Weld Range, in the Murchison region of Western Australia, was undertaken using classification and ordination analysis of quadrat data. A total of 239 taxa (species, subspecies and varieties) and five hybrids of vascular plants were collected and identified from within the survey area. Of these, 229 taxa were native and 10 species were introduced. Eight priority species were located in this survey, six of these being new records for the Weld Range. Although no species endemic to the Weld Range were located in this survey, new populations of three priority listed taxa were identified which represent significant range extensions for these taxa of conservation significance. Eight floristic community types (six types, two of these subdivided into two subtypes each) were identified and described for the Weld Range, with the primary division in the classification separating a dolerite-associated floristic community from those on banded iron formation. Floristic communities occurring on BIF were found to be associated with topographic relief, underlying geology and soil chemistry. There did not appear to be any restricted communities within the landform, but some communities may be geographically restricted to the Weld Range. Because these communities on the Weld Range are so closely associated with topography and substrate, they are vulnerable to impact from mineral exploration and open cast mining. -

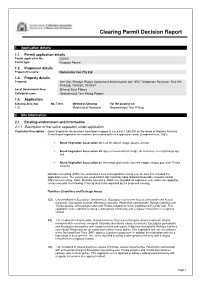

Clearing Permit Decision Report

Clearing Permit Decision Report 1. Application details 1.1. Permit application details Permit application No.: 3009/2 Permit type: Purpose Permit 1.2. Proponent details Proponent’s name: Hamersley Iron Pty Ltd 1.3. Property details Property: Iron Ore (Rhodes Ridge ) Agreement Authorisation Act 1972 , Temporary Reserves 70/4192, 70/4266, 70/4267, 70/4737 Local Government Area: Shire of East Pilbara Colloquial name: Geotechnical Test Pitting Project 1.4. Application Clearing Area (ha) No. Trees Method of Clearing For the purpose of: 112 Mechanical Removal Geotechnical Test Pitting 2. Site Information 2.1. Existing environment and information 2.1.1. Description of the native vegetation under application Vegetation Description Beard Vegetation Associations have been mapped at a scale of 1:250,000 for the whole of Western Australia. Three Beard Vegetation Associations are located within the application areas (Shepherd et al., 2001): • Beard Vegetation Association 18: Low woodland; mulga ( Acacia aneura ); • Beard Vegetation Association 29: Sparse low woodland; mulga, discontinuous in scattered groups; and • Beard Vegetation Association 82: Hummock grasslands, low tree steppe; snappy gum over Triodia wiseana . Mattiske Consulting (2008) has conducted a flora and vegetation survey over an area that included the application areas. The survey was conducted in April and May 2008 following favourable seasonal rainfall (Mattiske Consulting, 2008). Mattiske Consulting (2008) has recorded 25 vegetation units within the vegetation survey area with the following 11 being likely to be impacted by the proposed clearing: Flowlines (Creeklines and Drainage Areas): C2) Low woodland of Eucalyptus xerothermica, Eucalyptus victrix over Acacia citrinoviridis and Acacia maitlandii, Gossypium australe, Melaleuca lasiandra, Petalostylis labicheoides, Rulingia luteiflora over Triodia epactia, Chrysopogon fallax and Triodia pungens on minor creeklines with sandy soils. -

Palatability of Plants to Camels (DBIRD NT)

Technote No. 116 June 2003 Agdex No: 468/62 ISSN No: 0158-2755 The Palatability of Central Australian Plant Species to Camels Dr B. Dorges, Dr J. Heucke, Central Australian Camel Industry Association and R. Dance, Pastoral Division, Alice Springs BACKGROUND About 600,000 camels (Camelus dromedarius) are believed to inhabit the arid centre of Australia, mainly in South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. Most of these camels are feral. A small camel industry has developed, which harvests selected animals for domestic and export markets, primarily for meat. Camels can eat more than 80% of the common plant species found in Central Australia. Some plant species are actively sought by camels and may need to be protected. METHOD Observations of grazing preferences by camels were made periodically for up to 12 years on five cattle stations in Central Australia. Where camels were accustomed to the presence of humans, it was possible to observe their grazing preferences from a few metres. Radio transmitters were fitted on some camels for easy detection and observation at any time. These evaluations were used to establish a diet preference or palatability index for observed food plants. Table 1. Palatability index for camels Index Interpretation 1 only eaten when nothing else is available 2 rarely eaten 3 common food plant 4 main food plant at times 5 preferred food plant 6 highly preferred food plant 7 could be killed by camel browsing More information can be obtained from the web site of the Central Australian Camel Industry Association http://www.camelsaust.com.au 2 RESULTS Table 2. -

Vegetation and Soil Assessment of Selected Waterholes of the Diamantina and Warburton Rivers, South Australia, 2014-2016

Vegetation and Soil Assessment of Selected Waterholes of the Diamantina and Warburton Rivers, South Australia, 2014-2016 J.S. Gillen June 2017 Report to the South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board Fenner School of Environment & Society, Australian National University, Canberra Disclaimer The South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board, and its employees do not warrant or make any representation regarding the use, or results of use of the information contained herein as to its correctness, accuracy, reliability, currency or otherwise. The South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board and its employees expressly disclaim all liability or responsibility to any person using the information or advice. © South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board 2017 This report may be cited as: Gillen, J.S. Vegetation and soil assessment of selected waterholes of the Diamantina and Warburton Rivers, South Australia, 2014-16. Report by Australian National University to the South Australian Arid Lands Natural Resources Management Board, Pt Augusta. Cover images: Warburton River April 2015; Cowarie Crossing Warburton River May 2016 Copies of the report can be obtained from: Natural Resources Centre, Port Augusta T: +61 (8) 8648 5300 E: [email protected] Vegetation and Soil Assessment 2 Contents 1 Study Aims and Funding Context 6 2 Study Region Characteristics 7 2.1 Location 7 2.2 Climate 7 3 The Diamantina: dryland river in an arid environment 10 3.1 Methodology 11 3.2 Stages 12 -

Western Queensland

Western Queensland - Gulf Plains, Northwest Highlands, Mitchell Grass Downs and Channel Country Bioregions Strategic Offset Investment Corridors Methodology Report April 2016 Prepared by: Strategic Environmental Programs/Conservation and Sustainability Services, Department of Environment and Heritage Protection © State of Queensland, 2016. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5470. This publication can be made available in an alternative format (e.g. large print or audiotape) on request for people with vision impairment; phone +61 7 3170 5470 or email <[email protected]>. -

Literaturverzeichnis

Literaturverzeichnis Abaimov, A.P., 2010: Geographical Distribution and Ackerly, D.D., 2009: Evolution, origin and age of Genetics of Siberian Larch Species. In Osawa, A., line ages in the Californian and Mediterranean flo- Zyryanova, O.A., Matsuura, Y., Kajimoto, T. & ras. Journal of Biogeography 36, 1221–1233. Wein, R.W. (eds.), Permafrost Ecosystems. Sibe- Acocks, J.P.H., 1988: Veld Types of South Africa. 3rd rian Larch Forests. Ecological Studies 209, 41–58. Edition. Botanical Research Institute, Pretoria, Abbadie, L., Gignoux, J., Le Roux, X. & Lepage, M. 146 pp. (eds.), 2006: Lamto. Structure, Functioning, and Adam, P., 1990: Saltmarsh Ecology. Cambridge Uni- Dynamics of a Savanna Ecosystem. Ecological Stu- versity Press. Cambridge, 461 pp. dies 179, 415 pp. Adam, P., 1994: Australian Rainforests. Oxford Bio- Abbott, R.J. & Brochmann, C., 2003: History and geography Series No. 6 (Oxford University Press), evolution of the arctic flora: in the footsteps of Eric 308 pp. Hultén. Molecular Ecology 12, 299–313. Adam, P., 1994: Saltmarsh and mangrove. In Groves, Abbott, R.J. & Comes, H.P., 2004: Evolution in the R.H. (ed.), Australian Vegetation. 2nd Edition. Arctic: a phylogeographic analysis of the circu- Cambridge University Press, Melbourne, pp. marctic plant Saxifraga oppositifolia (Purple Saxi- 395–435. frage). New Phytologist 161, 211–224. Adame, M.F., Neil, D., Wright, S.F. & Lovelock, C.E., Abbott, R.J., Chapman, H.M., Crawford, R.M.M. & 2010: Sedimentation within and among mangrove Forbes, D.G., 1995: Molecular diversity and deri- forests along a gradient of geomorphological set- vations of populations of Silene acaulis and Saxi- tings. -

The Vegetation of the Western Australian Deserts

©Reinhold-Tüxen-Gesellschaft (http://www.reinhold-tuexen-gesellschaft.de/) Ber. d. Reinh.-Tüxen-Ges. 18, 219-228. Hannover 2006 The Vegetation of the Western Australian Deserts - Erika and Sandro Pignatti, Rom - Abstract The internal area of W. Australia has arid climate and conditions for plant growth are particularly difficult. The surface of this huge, almost uninhabited territory consists of four landscape systems: the Great Sandy Desert, the Little Sandy Desert, the Great Victoria Desert, the Gibson Desert. The four deserts extend between 21-26° of south- ern latitude, linking to the central Australian deserts and the Nullarbor Plain in the South. Meteorological stations are only in settlements of the surrounding semi-desert areas (Wiluna, Meekatharra, Cue, Warburton), and all show around 200-250 mm year- ly rainfall; in the centre of the deserts rainfall is still much lower, and indicated as “erratic and unreliable”; some areas may lack rain for several years. Despite of the par- ticularly severe ecological conditions, most of the surface is covered by vegetation (at least a discontinuous one) and during expeditions in 2001 and 2002 over 700 species were collected and more than 350 phytosociological relevés were carried out.Two main habitat types can be recognized: Mulga – scattered growth of treelets (Acacia aneura, generally about 3-4 m height), with open understorey (Senna, Eremophila, Solanum) and herbs usually covering less than 20 % of the surface; in the Gibson Desert mulga occurs mainly on hard rock sub- strate (granite, laterite). Because of the discontinuous plant cover, fire can spread only over limited areas. Spinifex – Quite a compact cover of perennial grasses (several species of Triodia, with sharply pointed leaves in dense tussocks 3-5 dm high, panicles up to 1 m and high- er) in monospecific populations covering 60-80 % of the surface; in the sandy deserts, on siliceous sand. -

Sites of Botanical Significance Vol1 Part1

Plant Species and Sites of Botanical Significance in the Southern Bioregions of the Northern Territory Volume 1: Significant Vascular Plants Part 1: Species of Significance Prepared By Matthew White, David Albrecht, Angus Duguid, Peter Latz & Mary Hamilton for the Arid Lands Environment Centre Plant Species and Sites of Botanical Significance in the Southern Bioregions of the Northern Territory Volume 1: Significant Vascular Plants Part 1: Species of Significance Matthew White 1 David Albrecht 2 Angus Duguid 2 Peter Latz 3 Mary Hamilton4 1. Consultant to the Arid Lands Environment Centre 2. Parks & Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory 3. Parks & Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory (retired) 4. Independent Contractor Arid Lands Environment Centre P.O. Box 2796, Alice Springs 0871 Ph: (08) 89522497; Fax (08) 89532988 December, 2000 ISBN 0 7245 27842 This report resulted from two projects: “Rare, restricted and threatened plants of the arid lands (D95/596)”; and “Identification of off-park waterholes and rare plants of central Australia (D95/597)”. These projects were carried out with the assistance of funds made available by the Commonwealth of Australia under the National Estate Grants Program. This volume should be cited as: White,M., Albrecht,D., Duguid,A., Latz,P., and Hamilton,M. (2000). Plant species and sites of botanical significance in the southern bioregions of the Northern Territory; volume 1: significant vascular plants. A report to the Australian Heritage Commission from the Arid Lands Environment Centre. Alice Springs, Northern Territory of Australia. Front cover photograph: Eremophila A90760 Arookara Range, by David Albrecht. Forward from the Convenor of the Arid Lands Environment Centre The Arid Lands Environment Centre is pleased to present this report on the current understanding of the status of rare and threatened plants in the southern NT, and a description of sites significant to their conservation, including waterholes.