Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Experimental Activism at UCSC, 1965-1970

1 Experimental Activism at UCSC, 1965-1970 By Robbie Stockman The 1960s shifted Americans' consciousness from complacency to dissatisfaction and revolt. The Civil Rights, Free Speech, Third World and antiwar movements together with the hippie subculture plunged the nation into chaotic liberation. In response to student concerns, University of California administrators created an ideal learning experiment at Santa Cruz. UC president Clark Kerr, UC Dean of Academic Planning Dean McHenry and University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) history professor Page Smith dedicated the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) to undergraduate education. Through a series of academic reforms and innovative techniques, UCSC administrators and faculty created an intellectually stimulating, communal university. Students at UCSC were compelled to create the culture of their university in this tumultuous time. Though UCSC student activism involved intellectual discussion and peaceful protest, they were ineffective at creating social change and as the campus developed, UC Berkeley and San Francisco State University (SFSU) began to control the direction of UCSC thought and action. UCSC: The Creation of an Aesthetic The dilemma at previous universities resulted from professors torn between their own research and educating undergraduate students. In the "publish or perish" world of higher education, professors focused mostly on their own research at the expense of student learning. UCLA history professor Page Smith considered such actions wasteful, considering -

Signature ---'~L--"-:-~=--~-'-- '___ I/~OO Et

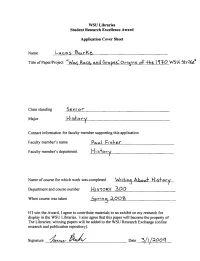

WSU Libraries Student Researcb Excellence Award Application Cover Sbeet Name LlAc.a.s B\ArKe. Title of Paper/Project I'WoJj R~c.E9r c'J\d grg,pes: Ori~i'n5 of +he 1110 W5U 5tril<e\l Class standing Senior Major Contact infonnation for faculty member supporting this application Faculty member's name Po..lA.\ E--,--,i~~h",--,-"""e,,-( _ Faculty member's department _Hi~+ory Name of course for which work was completed Wri-}..in~ Abo\.C.± H"6+~ry Department and course number J:{......l =S--!.1'...:::O:...:.R...:..y~-==3:<...O;o......::O=___ _ When course was taken If! win the Award, I agree to contribute materials to an exhibit on my research for display in the WSU Libraries. I also agree that this paper will become the property of The Libraries; winning papers will be added to the WSU Research Exchange (online research and publication repository). Signature -----'~L--"-:-~=--~-'--_'___ Date 3/I /~OO et ~I WAR, RACE. AND GRAPES: ORIGINS OF TIlE 1970 WASHINGTON STATE UNNERSITY STRIKE Lucas Burke History 300 Spring 2008 Early historians ofthe 1960s provided a narrow and limited view ofthe student protest movement in the United States by emphasizing national student organizations, predominately Students for a Democratic Society (SOS), as the solidifying force for activism on campuses across the United States. I However, recent historians have deemphasized the role ofSOS in the broader national student protest movement and no longer portray student activism as monolithic or unified.2 Furthermore, some historians, especially Caroline Hoefferle, have emphasized that student activism differed among universities because protests were a reaction to local issues as much as national themes.3 As a result, popular student protests, such as the demonstrations held at the University ofCalifornia-Berkeley and Columbia University, cannot define the broader student movement. -

Governmental Response to Campus Unrest

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 22 Issue 3 Article 6 1971 Governmental Response to Campus Unrest Bruce R. Hopkins John H. Myers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bruce R. Hopkins and John H. Myers, Governmental Response to Campus Unrest, 22 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 408 (1971) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol22/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. [Vol. 22: 408 Governmental Response to Campus Unrest Bruce R. Hopkins John H. Myers I. CAMPUS UNREST: ITS CONTEMPORARY NATURE AND ORIGINS A LTHOUGH the phenomenon of campus unrest has pervaded the United States in recent years, campus activism is not new to this country. Instances of student and faculty disturbances punctuate our history. As Julian H. Levi has written: "Neither student unrest, nor political at- tack is novel .... These issues, THE AUTHORS: BRUCE R. HOPKINS as well as the existence of col- (B.A., University of Michigan; J.D and universities antedate LLM., George Washington University) leges is a member of the District of Columbia the founding of the republic Bar and a practicing attorney in Wash- itself."' ington, D. C. JOHN H. MYERS (A.B., Princeton University; J.D., University of Moreover, campus unrest Michigan; LL.M., Georgetown Univer- has not been an uncommon oc- sity) is a member of the District of Co- lumbia, Maryland, U.S. -

Governmental Response to Campus Unrest Bruce R

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 22 | Issue 3 1971 Governmental Response to Campus Unrest Bruce R. Hopkins John H. Myers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bruce R. Hopkins and John H. Myers, Governmental Response to Campus Unrest, 22 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 408 (1971) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol22/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. [Vol. 22: 408 Governmental Response to Campus Unrest Bruce R. Hopkins John H. Myers I. CAMPUS UNREST: ITS CONTEMPORARY NATURE AND ORIGINS A LTHOUGH the phenomenon of campus unrest has pervaded the United States in recent years, campus activism is not new to this country. Instances of student and faculty disturbances punctuate our history. As Julian H. Levi has written: "Neither student unrest, nor political at- tack is novel .... These issues, THE AUTHORS: BRUCE R. HOPKINS as well as the existence of col- (B.A., University of Michigan; J.D and universities antedate LLM., George Washington University) leges is a member of the District of Columbia the founding of the republic Bar and a practicing attorney in Wash- itself."' ington, D. C. JOHN H. MYERS (A.B., Princeton University; J.D., University of Moreover, campus unrest Michigan; LL.M., Georgetown Univer- has not been an uncommon oc- sity) is a member of the District of Co- lumbia, Maryland, U.S. -

National War Protests 1970

National events leading up to the decisions of the Tuck School faculty on May 8, 1970, regarding classes for the balance of the school year On April 30, 1970, President Nixon announced the expansion of the Vietnam War into Cambodia. On May 1, protests on college campuses and in cities throughout the U.S. began. In Seattle, over a thousand protestors gathered at the Federal Courthouse and cheered speakers. At the University of Maryland, an estimated 1,500 students vandalized an armory building where Air Force Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) classes were held. And at the University of Cincinnati, a number of demonstrators were arrested after they conducted a sit-in and blocked a busy intersection in the middle of the city. Other students such as at Princeton University protested by cutting classes and sought to organize a nationwide student strike. At Kent State University in Ohio, a demonstration with about 500 students was held on the Commons. On May 2, students burned down the ROTC building at Kent State. On May 4, poorly-trained National Guardsmen confronted and killed four students while injuring ten others by bullets during a large protest demonstration at the college. Soon, more than 450 university, college and high school campuses across the country were shut down by student strikes and both violent and non-violent protests that involved more than 4 million students. On May 7, violent protests began at the University of Washington with some students smashing windows in their Applied Physics laboratory and throwing rocks at the police while chanting "the pigs are coming!” On May 8, ten days after Nixon announced the Cambodian invasion (and 4 days after the Kent State shootings), 100,000 protesters gathered in Washington and another 150,000 in San Francisco. -

Historical Collections

Historical Collections proquest.com To talk to the sales department, contact us at 1-800-779-0137 or [email protected]. Table of Contents HISTORY & SOCIAL CHANGE ...............................................................3 Black History .............................................................................................................................3 Cultural History ..........................................................................................................................6 Early Modern History ................................................................................................................7 Global Issues .............................................................................................................................7 Indigenous Peoples ..................................................................................................................9 Latino History .............................................................................................................................9 Military & Diplomatic History ..................................................................................................9 U.K. History ...............................................................................................................................11 U.S. History ...............................................................................................................................12 Women’s History .....................................................................................................................16 -

{Rje ©Ttfee Chronicle

{Rje ©ttfee Chronicle EXTRA Volume 65, Number 135 Duke University, Durham, North Carolina Sunday, May 17, 1970 Anti-war rally hears Fonda, Davis, Lane By David Pace author of "Rush to Judgment," were Managing Editor arrested and confined to the fort for passing Special to the Chronicle out leaflets to GI's explaining their rights in FAYETTEVILLE, N.C- Nearly 1500 the Army. people descended on Ft, Bragg here The rally, which lasted for nearly three yesterday, some distributing leaflets, but most talking to GI's in an effort to gain hours, featured speeches by Fonda, Rennie support within the military for the Davis, a member of the Chicago 8, Lane, and disengagement of the United States from the several members of the local GI's united war in Indochina. against the war in Vietnam. The speakers The action at Ft. Bragg followed a rally in were disrupted several times by hecklers Rowan Street Park in downtown, from the crowd. Fayetteville attended by over 3000 people.' Lane brought the overheated crowd to The rally and the discussion at Ft. Bragg their feet with a burst of applause when he marked the first time in recent months that said: a significant number of blacks participated "Nixon is scared because we have closed in the anti-war movement. down the colleges of this country and 13 arrests because we have cancelled Armed Forces Thirteen people, including actress Jane Day. Fonda, singer Barbara Dane, and Mark Lane, "They have Judge Hoffman, but we have Jane Fonda speaking at yesterday's anti-war fally in Fayetteville. -

The Class of 1970 Fiftieth Reunion Book

WESLEYAN 70 FIFTIETH REUNION | MAY 21–24, 2020 | WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY WESLEYAN 70 FIFTIETH REUNION | MAY 21–24, 2020 | WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY Dear Classmates, I have always felt lucky to have been at Wesleyan from 1966–1970. We were able to experience the conflict and change of those years in a safe environment that encouraged learning, arguing, and experimentation. So, when Kate Quigley Lynch asked me to edit our fiftieth reunion yearbook, I was happy to take the job. Ted Reed, a Wesleyan roommate and former Miami Herald reporter, agreed to be my partner in creating the book. Our goals were to let everybody know what our classmates have been doing for the past half century, to celebrate the lives of classmates who have died, and to honor the professors who were important to us. Additionally, we hoped that through preparing essays, compiling Argus stories, and chronicling outside events, we could help you remember not only our time on campus, but also the drama of the unique period when we were there. Jeff Sarles did a terrific job of finding, organizing, and writing captions for photos highlighting events happening in the outside world during our Wesleyan years. Much of this work is in the book. His full presentation is available on the class page (www.wesleyan.edu/classof1970) and will be played as a slide show during reunion weekend. John Sheffield, Maurice Hakim, and Jeremy Serwer read every Argus edition published during our time at Wesleyan and identified stories of interest. Many of you wrote heartfelt remembrances of classmates who died and others helped identify photos. -

Who Killed the Berkeley School?

Who Killed the Berkeley School? WHO KILLED THE BERKELEY SCHOOL? S TRUGGLES OVER RADICAL CRIMINOLOGY Herman & Julia Schwendinger Who Killed the Berkeley School? Struggles Over Radical Criminology Herman Schwendinger, 2014 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ This work is Open Access, which means that you are free to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors, that you do not use this work for commercial gain in any form whatso ever, and that you in no way, alter, transform, or build upon the work outside of its normal use in academic scholarship without express permission of the author and the publisher of this volume. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. First published in 2014 by Thought | Crimes an imprint of http://punctumbooks.com & design/layout: pj lilley and the full book is available for download via our Open Monograph Press website (a Public Knowledge Project) at: http://www.thoughtcrimespress.org a project of the Critical Criminology Working Group, (publishers of the Open Access Journal: Radical Criminology): http://journal.radicalcriminology.org Contact: Jeff Shantz (Editor), Dept. of Criminology, KPU 12666 72 Ave. Surrey, BC V3W 2M8 ISBN-13: 978-0615990934 ISBN-10: 0615990932 To Julia (1926–2013) Contents Foreword “Radical Criminology Lives” i (Jeff Shantz) Introduction: Déjà Vu 1 1 | Gilbert Geis’ Autopsy 3 2 | How Does It Really Add Up? 11 3 | Fighting “Friendly Fascists” 33 4 | “Pigs Off Campus!” 59 Operating -

A History of the New Left at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2007 "Shut It Down, Open It Up": A History of the New Left at the University Of Virginia, Charlottesville Thomas M. Hanna Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/693 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Shut It Down, Open It Up": A History of the New Left at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University. by Thomas Matthew Hanna B.A. Virginia Commonwealth University, 2005 Dr. Timothy N. Thurber, Director of Graduate Studies, History Department Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia December 2007 Acknowledgment I would like to thank my loving wife Caroline and my incredibly supportive parents. Without them none of this would have been possible. I would also like to thank all of my professors at Virginia Commonwealth University, especially my advisor Dr. Thurber, my thesis committee members Dr. Fronc and Dr. Newmann, Dr. Kneebone and Dr. Herman, and Dr. Deal at the Library of Virginia. Last but not least, I would like to thank Dr. Gaston at the University of Virginia and Thomas Gardner for allowing me to interview them for this thesis, Table of Contents List of Abbreviations .. -

Student Protest and the University of New Hampshire in May 1970

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Honors Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2020 The Resistance: Student Protest and the University of New Hampshire in May 1970 Abigeal Wright University of New Hampshire - Main Campus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/honors Part of the Other History Commons, and the Social History Commons Recommended Citation Wright, Abigeal, "The Resistance: Student Protest and the University of New Hampshire in May 1970" (2020). Honors Theses and Capstones. 491. https://scholars.unh.edu/honors/491 This Senior Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Resistance: Student Protest and the University of New Hampshire in May 1970 Abigeal Wright University of New Hampshire Department of History Senior Honors Thesis May 2020 Professor Jason Sokol, Advisor 1 “The basic purpose of a university has always been not solely to provide an encounter with stockpiles of knowledge, but to enable the young to discover and pursue new questions, to develop a spirit of critical inquiry and to test accepted propositions. This theoretical definition of the university’s function should now become, as the students see it, the literal one; and the results are as unsettling as they are promising and enormously exciting.” -Norman Cousins, Saturday Review 2 Introduction In May of 1970, the University of New Hampshire had armed National Guardsmen stationed less than two miles from campus awaiting their chance to quell any disturbances that may arise.