RECOMMENDATIONS for Domestic Sheep and Goat Management in Wild Sheep Habitat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Ammotragus Lervia) in Northern Algeria? Farid Bounaceur, Naceur Benamor, Fatima Zohra Bissaad, Abedelkader Abdi, Stéphane Aulagnier

Is there a future for the last populations of Aoudad (Ammotragus lervia) in northern Algeria? Farid Bounaceur, Naceur Benamor, Fatima Zohra Bissaad, Abedelkader Abdi, Stéphane Aulagnier To cite this version: Farid Bounaceur, Naceur Benamor, Fatima Zohra Bissaad, Abedelkader Abdi, Stéphane Aulagnier. Is there a future for the last populations of Aoudad (Ammotragus lervia) in northern Algeria?. Pakistan Journal of Zoology, 2016, 48 (6), pp.1727-1731. hal-01608784 HAL Id: hal-01608784 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01608784 Submitted on 27 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 48(6), pp. 1727-1731, 2016. Is There a Future for the Last Populations of Aoudad (Ammotragus lervia) in Northern Algeria? Farid Bounaceur,1,* Naceur Benamor,1 Fatima Zohra Bissaad,2 Abedelkader Abdi1 and Stéphane Aulagnier3 1Research Team Conservation Biology in Arid and Semi Arid, Laboratory of Biotechnology and Nutrition in Semi-Arid. Faculty of Natural Sciences and Life, University Campus Karmane Ibn Khaldoun, Tiaret, Algeria 14000 2Laboratory Technologies Soft, Promotion, Physical Chemistry of Biological Materials and Biodiversity, Science Faculty, University M'Hamed Bougara, Article Information BP 35000 Boumerdes, Algeria Received 31 August 2015 3 Revised 25 February 2016 Behavior and Ecology of Wildlife, I.N.R.A., CS 52627, 31326 Accepted 23 April 2016 Castanet Tolosan Cedex, France Available online 25 September 2016 Authors’ Contribution A B S T R A C T FB conceived and designed the study. -

REPORT on TRANSBOUNDARY CONSERVATION HOTSPOTS for the CENTRAL ASIAN MAMMALS INITIATIVE (Prepared by the Secretariat)

CONVENTION ON UNEP/CMS/COP13/Inf.27 MIGRATORY 8 January 2020 SPECIES Original: English 13th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Gandhinagar, India, 17 - 22 February 2020 Agenda Item 26.3 REPORT ON TRANSBOUNDARY CONSERVATION HOTSPOTS FOR THE CENTRAL ASIAN MAMMALS INITIATIVE (Prepared by the Secretariat) Summary: This report was developed with funding from the Government of Switzerland within the frame of the Central Asian Mammals Initiative (CAMI) (Doc. 26.3.5) to identify transboundary conservation hotspots and develop recommendations for their conservation. The report builds on existing projects, in particular, the CAMI Linear Infrastructure and Migration Atlas (see Inf.Doc.19) and focusses on the same species and geographical area. The study was discussed during the CAMI Range State Meeting held from 25-28 September 2019 in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia where participants reviewed the pre-identified areas. Their comments are incorporated in this report. Participants also provided new information about important transboundary sites from Bhutan, India, Nepal and Pakistan and recommended to send the report for final review to Range States and experts. It was also recommended that the final report covers all CAMI species as adopted at COP13. This report is therefore a final draft with the last step to expand the geographical and species scope and finalize the report to be undertaken after COP13. Mapping Transboundary Conservation Hotspots for the Central Asian Mammals Initiative Photo credit: Viktor Lukarevsky Report – Draft 5 incorporating comments made during the CAMI Range States Meeting on 25-28 September 2019 in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. The report does not yet consider the Urial, Persian leopard and Gobi bear as CAMI species pending decision at the CMS COP13, as well as the proposed expansion of the geographic and species scope to include the entire CAMI region in this study. -

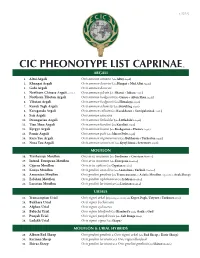

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Early Survival of Punjab Urial

394 Early survival of Punjab urial Ghulam Ali Awan, Marco Festa-Bianchet, and Jean-Michel Gaillard Abstract: There is almost no information on age-specific survival of Asiatic ungulates based on mark–recapture studies. Survival of marked Punjab urial (Ovis vignei punjabiensis Lydekker, 1913) aged 0–2 years was studied in the Salt Range, Pakistan, in 2001–2005. Male lambs were heavier than females at birth. The relationship between litter size and birth mass varied among years, with a tendency for twins to be lighter than singletons. Birth mass had a positive but nonsignificant relation with survival to 1 year. Neither sex nor litter size affected survival to 1 year, which averaged 55% (95% CI = 41%–68%). There was no sex effect on survival of yearlings, which averaged 88% (95% CI = 4%–100%). Although sur- vival of lambs and yearlings was similar to that reported for other ungulates, apparent survival of 2- and 3-year-olds was very low at only 47%, possibly because of emigration. Early survival in this protected area is adequate to allow population growth, but more data are required on adult survival. Re´sume´ : En l’absence de suivis par capture–marquage–recapture, il n’y a pratiquement pas d’information disponible sur la variation des taux de survie en fonction de l’aˆge pour les espe`ces d’ongule´s asiatiques. Nous avons e´tudie´ la survie d’urials du Punjab (Ovis vignei punjabiensis Lydekker, 1913) individuellement marque´s entre 0 et 2 ans dans la re´gion de la chaıˆne de Salt, au Pakistan, entre 2001 et 2005. -

Status and Red List of Pakistan's Mammals

SSttaattuuss aanndd RReedd LLiisstt ooff PPaakkiissttaann’’ss MMaammmmaallss based on the Pakistan Mammal Conservation Assessment & Management Plan Workshop 18-22 August 2003 Authors, Participants of the C.A.M.P. Workshop Edited and Compiled by, Kashif M. Sheikh PhD and Sanjay Molur 1 Published by: IUCN- Pakistan Copyright: © IUCN Pakistan’s Biodiversity Programme This publication can be reproduced for educational and non-commercial purposes without prior permission from the copyright holder, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior permission (in writing) of the copyright holder. Citation: Sheikh, K. M. & Molur, S. 2004. (Eds.) Status and Red List of Pakistan’s Mammals. Based on the Conservation Assessment and Management Plan. 312pp. IUCN Pakistan Photo Credits: Z.B. Mirza, Kashif M. Sheikh, Arnab Roy, IUCN-MACP, WWF-Pakistan and www.wildlife.com Illustrations: Arnab Roy Official Correspondence Address: Biodiversity Programme IUCN- The World Conservation Union Pakistan 38, Street 86, G-6⁄3, Islamabad Pakistan Tel: 0092-51-2270686 Fax: 0092-51-2270688 Email: [email protected] URL: www.biodiversity.iucnp.org or http://202.38.53.58/biodiversity/redlist/mammals/index.htm 2 Status and Red List of Pakistan Mammals CONTENTS Contributors 05 Host, Organizers, Collaborators and Sponsors 06 List of Pakistan Mammals CAMP Participants 07 List of Contributors (with inputs on Biological Information Sheets only) 09 Participating Institutions -

Haplogroup Relationships Between Domestic and Wild Sheep Resolved Using a Mitogenome Panel

Heredity (2011) 106, 700–706 & 2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0018-067X/11 www.nature.com/hdy ORIGINAL ARTICLE Haplogroup relationships between domestic and wild sheep resolved using a mitogenome panel JRS Meadows1,3, S Hiendleder2 and JW Kijas1 1CSIRO Livestock Industries, St Lucia, Queensland, Australia and 2School of Agriculture, Food and Wine & Research Centre for Reproductive Health, School of Animal and Veterinary Science, University of Adelaide, Roseworthy, South Australia, Australia Five haplogroups have been identified in domestic sheep 920 000±190 000 years ago based on protein coding through global surveys of mitochondrial (mt) sequence sequence. The utility of various mtDNA components to inform variation, however these group classifications are often the true relationship between sheep was also examined with based on small fragments of the complete mtDNA sequence; Bayesian, maximum likelihood and partitioned Bremmer sup- partial control region or the cytochrome B gene. This study port analyses. The control region was found to be the mtDNA presents the complete mitogenome from representatives of component, which contributed the highest amount of support to each haplogroup identified in domestic sheep, plus a sample the tree generated using the complete data set. This study of their wild relatives. Comparison of the sequence success- provides the nucleus of a mtDNA mitogenome panel, which can fully resolved the relationships between each haplogroup be used to assess additional mitogenomes and serve as a and provided insight into the relationship with wild sheep. reference set to evaluate small fragments of the mtDNA. The five haplogroups were characterised as branching Heredity (2011) 106, 700–706; doi:10.1038/hdy.2010.122; independently, a radiation that shared a common ancestor published online 13 October 2010 Keywords: Ovis aries; domestication; mitochondria; genome; diversity Introduction Pedrosa et al., 2005; Pereira et al., 2006; Tapio et al., 2006; Meadows et al., 2007). -

Cervid Mixed-Species Table That Was Included in the 2014 Cervid RC

Appendix III. Cervid Mixed Species Attempts (Successful) Species Birds Ungulates Small Mammals Alces alces Trumpeter Swans Moose Axis axis Saurus Crane, Stanley Crane, Turkey, Sandhill Crane Sambar, Nilgai, Mouflon, Indian Rhino, Przewalski Horse, Sable, Gemsbok, Addax, Fallow Deer, Waterbuck, Persian Spotted Deer Goitered Gazelle, Reeves Muntjac, Blackbuck, Whitetailed deer Axis calamianensis Pronghorn, Bighorned Sheep Calamian Deer Axis kuhili Kuhl’s or Bawean Deer Axis porcinus Saurus Crane Sika, Sambar, Pere David's Deer, Wisent, Waterbuffalo, Muntjac Hog Deer Capreolus capreolus Western Roe Deer Cervus albirostris Urial, Markhor, Fallow Deer, MacNeil's Deer, Barbary Deer, Bactrian Wapiti, Wisent, Banteng, Sambar, Pere White-lipped Deer David's Deer, Sika Cervus alfredi Philipine Spotted Deer Cervus duvauceli Saurus Crane Mouflon, Goitered Gazelle, Axis Deer, Indian Rhino, Indian Muntjac, Sika, Nilgai, Sambar Barasingha Cervus elaphus Turkey, Roadrunner Sand Gazelle, Fallow Deer, White-lipped Deer, Axis Deer, Sika, Scimitar-horned Oryx, Addra Gazelle, Ankole, Red Deer or Elk Dromedary Camel, Bison, Pronghorn, Giraffe, Grant's Zebra, Wildebeest, Addax, Blesbok, Bontebok Cervus eldii Urial, Markhor, Sambar, Sika, Wisent, Waterbuffalo Burmese Brow-antlered Deer Cervus nippon Saurus Crane, Pheasant Mouflon, Urial, Markhor, Hog Deer, Sambar, Barasingha, Nilgai, Wisent, Pere David's Deer Sika 52 Cervus unicolor Mouflon, Urial, Markhor, Barasingha, Nilgai, Rusa, Sika, Indian Rhino Sambar Dama dama Rhea Llama, Tapirs European Fallow Deer -

Transcaspian Urial

Transcaspian urial ... the ultimate ram! CAPRINAE TAG Why exhibit Transcaspian urials? • Amaze visitors with these impressive wild sheep. Males have curling horns (over 2½ feet long!) and luxurious ruffs of long hair on their necks! • Enhance your “spring baby boom” — this reliable breeder can have up to three lambs at a time! Guests and staff alike will marvel at the activity and playfulness of kids as they grow. • Weave together the stories of these wild sheep and their domestic descendants: the sheep in your petting zoo! A great way to illustrate the story behind the domestication of livestock. • Ensure an active exhibit that captures the attention of visitors with this lively, gregarious sheep that mixes well with other species. • TAG RECOMMENDATION: Institutions are encouraged to replace generic European mouflon with this SSP Asian sheep. MEASUREMENTS IUCN Stewardship Opportunities Length: 3.5-5 feet VULNERABLE Community-based conservation and management Height: 2.5-3 feet CITES I program for the mountain ungulates of Tajikistan. at shoulder www.wildlife-tajikistan.org/ Weight: 60-140 lbs ~ 6,000 in Dry mountains Western Asia the wild Argali (Asian wild sheep) Ecology and Conservation www.denverzoo.org/conservation/project02.html Care and Husbandry YELLOW SSP: 19.38 (57) in 5 AZA (+1 non-AZA) institutions (2019) Species coordinator: Jon Rolfs, San Diego Zoo Safari Park [email protected] ; 760-473-5248 Social nature: Herd-living. Usually kept as a breeding group: several females with one male. Multiple males can be housed together either in bachelor groups or with females (not recommended for genetic management). Mixed species: Mixes well with a variety of ungulates, including other caprids, wild cattle, and various deer. -

ACE Appendix

CBP and Trade Automated Interface Requirements Appendix: PGA August 13, 2021 Pub # 0875-0419 Contents Table of Changes .................................................................................................................................................... 4 PG01 – Agency Program Codes ........................................................................................................................... 18 PG01 – Government Agency Processing Codes ................................................................................................... 22 PG01 – Electronic Image Submitted Codes .......................................................................................................... 26 PG01 – Globally Unique Product Identification Code Qualifiers ........................................................................ 26 PG01 – Correction Indicators* ............................................................................................................................. 26 PG02 – Product Code Qualifiers ........................................................................................................................... 28 PG04 – Units of Measure ...................................................................................................................................... 30 PG05 – Scientific Species Code ........................................................................................................................... 31 PG05 – FWS Wildlife Description Codes ........................................................................................................... -

International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Argali Ovis Ammon

International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Argali Ovis ammon 1 This Single Species Action Plan has been prepared to assist the fulfillment of obligations under: Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) International Single Species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Argali Ovis ammon CMS Technical Series No. XX April 2014 Prepared and printed with funding from 2 Support for this action plan: The development and production of this action plan has been achieved with the financial support of the European Union via the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH (GIZ) in the framework of the FLERMONECA Regional Project Forest and Biodiversity Governance Including Environmental Monitoring. Compiled by: David Mallon, Navinder Singh, Christiane Röttger1, UNEP / CMS Secretariat, United Nations Premises, Platz der Vereinten Nationen 1 , 53113 Bonn, Germany E-mail for correspondence: [email protected] List of Contributors: Muhibullah Fazli (Afghanistan); Alexander Berber, Maksim Levitin (Kazakhstan); Askar Davletbakov, Nadezhda Emel’yanova, Almaz Musaev, (Kyrgyzstan); Tarun Kathula (India); Onon Yondon, Sukh Amgalanbaatar (Mongolia); Dinesh Prasad Parajuli (Nepal); Nurali Saidov, Munavvar Alidodov, Abdulkadyrkhon Maskaev (Tajikistan); Tatiana Yudina (Russian Federation); Alexandr Grigoryants (Uzbekistan); Sergey Sklyarenko (Association for the Conservation of Biodiversity of Kazakhstan, ACBK); Gerhard Damm, Kai-Uwe Wollscheid (International Council for Game and Wildlife -

Wild, Feral and Domesticated Breeds of Sheep G

Seasonal cycles in the blood plasma concentration of FSH, inhibin and testosterone, and testicular size in rams of wild, feral and domesticated breeds of sheep G. A. Lincoln, C. E. Lincoln and A. S. McNeilly MRC Reproductive Biology Unit, Centre for Reproductive Biology, 37 Chalmers Street, Edinburgh EH3 9EW, UK; and *Kirkton Cottages, Auchtertool, Fife KY2 5XQ, UK Summary. Seasonal cycles in testicular activity in rams were monitored in groups of wild (mouflon), feral (Soay) and domesticated breeds of sheep (Shetland, Blackface, Herdwick, Norfolk, Wiltshire, Portland and Merino) living outdoors near Edinburgh (56\s=deg\N).The changes in the blood plasma concentrations of FSH, inhibin and testoster- one, and the diameter of the testis were measured every half calendar month from 1 to 3 years of age. There were significant differences between breeds in the magnitude and timing of the seasonal reproductive cycle. In the mouflon rams, the seasonal changes were very pronounced with a 6\p=n-\15-foldincrease in the plasma concentrations of FSH, inhibin and testosterone from summer to autumn, and a late peak in testicular diameter in October. In the Soay rams and most of the domesticated breeds, the seasonal increase in the reproductive hormones occurred 1\p=n-\2months earlier with the peak in testicular size in September or October. In the two southern breeds (Portland and Merino), the early onset of testicular activity was more extreme with the seasonal maxi- mum in August. In cross-bred rams, produced by mating Soay ewes (highly seasonal breed) with Portland or Merino rams (less seasonal breeds), there was a seasonal repro- ductive cycle that was intermediate compared to that of the parents. -

Mixed-Species Exhibits with Pigs (Suidae)

Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) Written by KRISZTIÁN SVÁBIK Team Leader, Toni’s Zoo, Rothenburg, Luzern, Switzerland Email: [email protected] 9th May 2021 Cover photo © Krisztián Svábik Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 Use of space and enclosure furnishings ................................................................... 3 Feeding ..................................................................................................................... 3 Breeding ................................................................................................................... 4 Choice of species and individuals ............................................................................ 4 List of mixed-species exhibits involving Suids ........................................................ 5 LIST OF SPECIES COMBINATIONS – SUIDAE .......................................................... 6 Sulawesi Babirusa, Babyrousa celebensis ...............................................................7 Common Warthog, Phacochoerus africanus ......................................................... 8 Giant Forest Hog, Hylochoerus meinertzhageni ..................................................10 Bushpig, Potamochoerus larvatus ........................................................................ 11 Red River Hog, Potamochoerus porcus ...............................................................