Speculative Phantasms in Three English Chronicles of the 12Th and 13Th Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

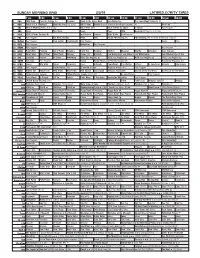

Sunday Morning Grid 5/1/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/1/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Boss Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Rescue Red Bull Signature Series (Taped) Å Hockey: Blues at Stars 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball First Round: Teams TBA. (N) Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Prerace NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program A History of Violence (R) 18 KSCI Paid Hormones Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Landscapes Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Space Edisons Biz Kid$ Celtic Thunder Legacy (TVG) Å Soulful Symphony 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Formula One Racing Russian Grand Prix. -

Fortean Times 338

THE X-FILES car-crash politics jg ballard versus ronald reagan cave of the witches south america's magical murders they're back: is the truth still out there? phantom fares japan's ghostly cab passengers THE WORLD’S THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA WWW.FORTEANTiMES.cOM FORTEAN TiMES 338 chimaera cats • death by meteorite • flat earth rapper • ancient greek laptop WEIRDES NEWS T THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA www.forteantimes.com ft338 march 2016 £4.25 THE SEcRET HiSTORy OF DAviD bOWiE • RETuRN OF THE x-FiLES • cAvE OF THE WiTcHES • AuTOMATic LEPREcHAuNSP • jAPAN'S GHOST ACE ODDITY from aliens to the occult: the strange fascinations of daVid b0Wie FA RES bogey beasts the shape-shifting monsters of british folklore mystery moggies on the trail of alien big MAR 2016 cats in deepest suffolk Fortean Times 338 strange days Japan’s phantom taxi fares, John Dee’s lost library, Indian claims death by meteorite, cretinous criminals, curious cats, Harry Price traduced, ancient Greek laptop, Flat Earth rapper, CONTENTS ghostly photobombs, bogey beasts – and much more. 05 THE CONSPIRASPHERE 23 MYTHCONCEPTIONS 05 EXTRA! EXTRA! 24 NECROLOG the world of strange phenomena 15 ALIEN ZOO 25 FAIRIES & FORTEANA 16 GHOSTWATCH 26 THE UFO FILES features COVER STORY 28 THE MAGE WHO SOLD THE WORLD From an early interest in UFOs and Aleister Crowley to fl irtations with Kabbalah and Nazi mysticism, David Bowie cultivated a number of esoteric interests over the years and embraced alien and occult imagery in his costumes, songs and videos. DEAN BALLINGER explores the fortean aspects and influences of the late musician’s career. -

LEASK-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (1.565Mb)

WRAITHS AND WHITE MEN: THE IMPACT OF PRIVILEGE ON PARANORMAL REALITY TELEVISION by ANTARES RUSSELL LEASK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2020 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Timothy Morris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Timothy Richardson Copyright by Antares Russell Leask 2020 Leask iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • I thank my Supervising Committee for being patient on this journey which took much more time than expected. • I thank Dr. Tim Morris, my Supervising Professor, for always answering my emails, no matter how many years apart, with kindness and understanding. I would also like to thank his demon kitten for providing the proper haunted atmosphere at my defense. • I thank Dr. Neill Matheson for the ghostly inspiration of his Gothic Literature class and for helping me return to the program. • I thank Dr. Tim Richardson for using his class to teach us how to write a conference proposal and deliver a conference paper – knowledge I have put to good use! • I thank my high school senior English teacher, Dr. Nancy Myers. It’s probably an urban legend of my own creating that you told us “when you have a Ph.D. in English you can talk to me,” but it has been a lifetime motivating force. • I thank Dr. Susan Hekman, who told me my talent was being able to use pop culture to explain philosophy. It continues to be my superpower. • I thank Rebecca Stone Gordon for the many motivating and inspiring conversations and collaborations. • I thank Tiffany A. -

The Black Seal Number Three

Terra Occulta: Cages An Atlas of Strange By Nick Brownlow & Places P.J.Holden By Nick Brownlow, David Page 55 Conyers,Adam Crossingham & Daniel Harms False Mythologies: Page 4 How a Euro Cult Alien Landscape L.Abdul Baan © 2004 Manipulates Memory for Publishers: Unusual Suspects: the Benefit of The Black Seal is The Shragged Man Ghatanothoa published twice yearly by the By Brian Boyington By Wood Ingham Brichester Page 11 Page 60 University Press, 74 Union Street, Farnborough, Hampshire A Road Less Travelled: The Further Files of GU14 7QA United Kingdom A Rough Guide to Professor Grant ISSN: Fighting Evil in a Hot Emerson: Report on 1476-1939 Country NYC Burn Victim Product Code: By Jonathan Turner By Graeme Price BUP103E Page 13 Page 71 “We few, we happy few, we band of ruthless The Spiralling: Resolution Zero: bastards.” A PISCES Assignment The United Nations and Internet: into the Heart of the the Starkweather Moore The Black Seal’s web site is: Congo Sample file Conspiracy www.theblackseal.org By David Conyers By Daniel Harms, with Submissions: Page 27 David Conyers & Please check our web site for details of our Adam Crossingham submissions policy The British Museum: Page 73 d20 Cthulhu: London's Centres of All d20 Cthulhu material is presented in square Knowledge, part one Dangerous Places: brackets: [ ] or as d20 stat blocks By David Conyers Timsdown West Page 44 By Ben Counter Page 87 The BLACK SEAL #3 Rare and Unusual: Paranormal Artefacts at Contains: One Tibetan the British Museum God By David Conyers & William By Davide Mana Jones, with Phil Ward Page 91 Page 50 Volume 1 Number 3 Spring 2004 Welcome to the third issue of The Black Seal. -

Sunday Morning Grid 2/3/19 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/3/19 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) Pregame Road to the Super Bowl Tony Romo Sp. The Super Bowl Today (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Hockey Boston Bruins at Washington Capitals. (N) PGA Golf 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News NBA Basketball: Thunder at Celtics 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program 1 1 FOX Paid Program Fox News Sunday News PBC Inside PBC Boxing (N) PBA Bowling CP3 Celebrity Invitational. (Taped) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Martha Christina Suze Orman’s 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Feel Better Fast and Make It Last With Daniel Joni Mitchell Live at Isle 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

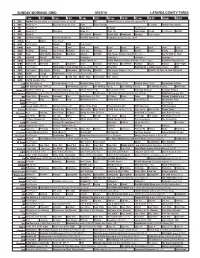

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/23/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 Am 7:30 8 Am 8:30 9 Am 9:30 10 Am 10:30 11 Am 11:30 12 Pm 12:30 2 CBS Football New York Giants Vs

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/23/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS Football New York Giants vs. Los Angeles Rams. (6:30) (N) NFL Football Raiders at Jacksonville Jaguars. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) News Figure Skating F1 Count Formula One Racing 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Regional Coverage. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Martha Hubert Baking Mexican 28 KCET Peep 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Rick Steves’ Europe Travel Skills (TVG) Å Age Fix With Dr. Youn 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Tigres República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Home Alone 2: Lost in New York ›› (1992) (PG) Zona NBA Next Day Air › (2009) Donald Faison. -

Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Spectral Science: Into the World of American Ghost Hunters Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3q71q8f7 Author Li, Janny Publication Date 2015 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Spectral Science: Into the World of American Ghost Hunters DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Anthropology by Janny Li Dissertation Committee: Chancellor’s Professor George Marcus, Chair Associate Professor Mei Zhan Associate Professor Keith Murphy 2015 ii © 2015 Janny Li ii DEDICATION To My grandmother, Van Bich Luu Lu, who is the inspiration for every big question that I ask. And to My sisters, Janet and Donna Li, with whom I never feel alone in this world. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS V CURRICULUM VITAE VII INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: A Case of Quasi-Certainty: William James and the 31 Making of the Subliminal Mind CHAPTER 2: Visions of Future Science: Inside a Ghost Hunter’s Tool Kit 64 CHAPTER 3: Residual Hauntings: Making Present an Intuited Past 108 CHAPTER 4: The Train Conductor: A Case Study of a Haunting 137 CONCLUSION 169 REFERENCES 174 iii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1. Séance at Rancho Camulos 9 Figure 2. Public lecture at Fort Totten 13 Figure 3. Pendulums and dowsing rods 15 Figure 4. Ad for “Ghost Hunters” 22 Figure 5. Selma Mansion 64 Figure 6. -

Haunted Middletown, Usa: an Analysis of Supernatural Beliefs of Protestants in Muncie, Indiana

HAUNTED MIDDLETOWN, USA: AN ANALYSIS OF SUPERNATURAL BELIEFS OF PROTESTANTS IN MUNCIE, INDIANA A THESIS SUMBITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS BY LAUREN HOLDITCH DR. CAILÍN MURRAY DR. PAUL WOHLT DR. JENNIFER ERICKSON BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, IN MAY 2013 1 Table of Contents Title Page 1 Table of Contents 2 Acknowledgements 4 Abstract 6 Chapter I: Introduction Ghosts in Contemporary America 8 Supernatural Scholarship and 12 Religious Context Purpose of this Study 16 Terminology 18 Chapter II: Literature Review Early English Ghost Beliefs 22 Migration of Ghost Beliefs 25 from England to America Spiritualism and Skepticism 28 Social Scientific Theories 32 Middletown, USA: Background 37 Research on Muncie, Indiana Chapter III: Methodology Utilization of Qualitative 41 Methods 2 Data Collection 43 Interviews 45 Chapter IV: Results Ghostly Experiences 48 Alternative Theories and 52 Demonic Forces The Holy Spirit as an 58 Anti-Viral System Paranormal Reality-based 63 Television Shows Chapter V: Discussion Lack of Discussion in Church 66 Church Transitions 69 David Hufford’s Experiential 71 Source Theory Role of the Media 72 Chapter VI: Conclusions 77 References 81 Appendix A – Interview Questions 87 Appendix B – Consent Form 88 Appendix C – Ghost Media Examples 90 3 Acknowledgements I would like to show my deepest appreciation to my committee members. First, my thanks to Dr. Jennifer Erickson, who was willing to join my committee, even though it was late in the process and I was already on the other side of the country. Despite all this, she provided me with wonderful perspective that helped shape the style of this thesis. -

September 2019 New Releases

September 2019 New Releases what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 72 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 13 FEATURED RELEASES SUBHUMANS - KMFDM - FIDDLER ON THE ROOF: CRISIS POINT PARADISE 2018 CAST ALBUM Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 45 Non-Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 49 Order Form 75 Deletions and Price Changes 78 800.888.0486 THE HILLS HAVE EYES 2 NOIR ARCHIVE VOLUME TO HELL AND BACK: 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 [LIMITED EDITION] 3: 1957-1960 (9-FILM THE KANE HODDER SUBHUMANS - DEIDRE & THE DARK - KMFDM - www.MVDb2b.com COLLECTION) STORY CRISIS POINT VARIETY HOUR PARADISE HILLS HAVE EYES 2, SEE YOU IN SEPTEMBER! THE HILLS HAVE EYES 2, Wes Craven’s 1984 follow up to his classic original 1977 film, finds the lone survivor of a cannibal tribe detouring a motocross team across the desert straight into a pack of devouring ogres! The Hills are alive with the sound of screaming! From ARROW VIDEO, THE HILLS HAVE EYES 2 bluray is packed with extras that includes a limited edition 40-page book. If blinding horror is what you’re Craven, then this sequel delivers the goods! THE HILLS HAVE EYES 2 will see you in September, and the ogres will sing ‘Bye-bye, so long, farewell!’ Priests who are able to turn into dinosaurs may be an overused theme in film (!) but nobody does it better than WILD EYE films! THE VELOCIPASTOR DVD and bluray finds a despondent priest moving to China to find himself, only to find he can turn into a giant dinosaur. -

P E R E G R I N E N a T I O

"The Toothsome Twosome" — Elric and Megumi © 2003 by Trinlay Khadro P E R E G R I N E N A T I O N S VOLUME THREE, NUMBER FOUR / JANUARY 2004 This Time ‘Round We Have: Silent eLOCutions / art by Trinlay Khadro / 3 Book Review by Lyn McConchie / art by Rod Marsden / 10 In the Interim: Fanzines Received / art by Marc Schirmeister / 11 The Agriculture and Cuisine of the Shire by E.B. Frohvet / art by Brad Foster / 12 Will the Real Swamp Thing Please Stand Up? / mascot art by Brad Foster / 15 Additional Art: Trinlay Khadro/ cover Alan White / masthead This version has the addresses of contributors removed, for privacy reasons. ________________________________________________________________________________ peregrination, n., L., A traveling, roaming, or wandering about; a journey. (The New Webster Encyclopedic Dictionary of the English Language, Avenel Books, New York: 1980). ________________________________________________________________________________ This issue is dedicated to the animals with whom many of us share our lives. They make us laugh and keep us warm (furry or not), and their departures are never easy. To all the critters in fandom, here's a scritch and a smooch. Thanks for joining us on the ride. ____________________________________________________________________________________ This issue of Peregrine Nations is a © 2004 J9 Press Publication edited and published by J. G. Stinson, P.O. Box 248, Eastlake, MI 49626-0248. Copies available for $2 or the Usual. A quarterly pubbing sked is intended. All material in this publication was contributed for one-time use only, and copyrights belong to the contributors. Contributions are welcome in the form of LoCs, articles, reviews, art, etc. -

Star Channels, Feb

FEBRUARY 3 - 9, 2019 staradvertiser.com WORLD’S BEST DAD Matt LeBlanc and Liza Snyder are back as the Burnses for a third season of their classic family sitcom Man With a Plan. LeBlanc plays Adam, a father and contractor, who struggles to keep control of his brood of three unpredictable children now that his wife, Andi, is back at work. Premiering Monday, Feb 4, on CBS. WEEKLY NEWS UPDATE LIVE @ THE LEGISLATURE Join Senate and House leadership as they discuss upcoming legislation and issues of importance to the community. TOMORROW, 8:30AM | CHANNEL 49 | olelo.org/49 olelo.org ON THE COVER | MAN WITH A PLAN Raising hellions Family sitcom ‘Man With a Plan’ being a stay-at-home mom to their three kids. even more flavor to the mixed bag of char- returns for a third season As a result, Adam has to pick up a greater share acters as Adam’s contracting assistant and of the child care duties, and he begins to learn close friend, Lowell. that his kids aren’t as simple or innocent as he When asked why he was drawn to the con- By Joy Doonan always thought they were. cept of “Man With a Plan,” LeBlanc has said TV Media Adam, a guy who seems to take very little se- that, being a father in real life, he wanted the riously and would rather have a beer and read opportunity to play the classic sitcom family tarting in 2006, Matt LeBlanc took a five- the paper than engage in the bureaucracies man on TV. -

Phil and Sara Whyman

Phil and Sara Whyman Manchester Haunted: Hello Phil and Sara, how are things at the moment with Dead Haunted Nights? Phil Whyman: Hey guys! We're working on some new ideas for 2012, but can't say too much at the moment. Sara Whyman: Hi, we’re just settling down after the Halloween rush, as you can imagine this is our busiest time of year. Like Phil says we have some new ideas that we’re looking at for 2012 and we’re starting to fill up the calendar with bookings. MH: For people who haven’t been on a Dead Haunted Night’s event yet, what can they expect? PW: We're well known for the relaxed and approachable manner in which we run our events, which I think is a vital part of putting our guests at ease (some are pretty nervous!). We aim to give guests a memorable ghost hunting event, where they can participate in such things as seances, glass work experiments, even ouija boards if they want, all under the supervision of our experienced team leaders. Incidentally, for those worried about taking part in experiments all participation is optional. And for peace of mind no team leader is permitted (apart from seances) to take part in any other experiment; as we therefore say, if it happens then it happens for real and not because we are faking anything. We believe we have the best, most trustworthy team leaders in the field working for us. SW: At Dead Haunted we try to give an insight Paranormal Investigation, we look at things more from logical scientific point of view.