Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6. June 08 AQUARIAN THEOSOPHIST Supplement V2

TThhee AAqquuaarriiaann TThheeoossoopphhiisstt Volume VIII #8 June 17, 2008 SUPPLEMENT p. 1 Email: [email protected] ARCHIVE: http://www.teosofia.com/AT.html IN SUPPORT OF JUSTICE FOR IN SUPPORT OF JUSTICEWILLIAM TO W.Q.J Q JUDGE “A Good Man’s Heart” This Supplement follows the declared aim to bring justice to bear in the ‘Judge Case’. WQJ, ‘the Raja’ as his friends called him, gave his life’s work in support of his teacher Mme Blavatsky and their joint cause, the modern Theosophical TABLE OF CONTENTS Movement, of which he was a champion and prime mover . IN SUPPORT OF JUSTICE FOR W.Q.J 1 LETTERS Contained here are copies of the letters sent MORELOS, MÉXICO 2 to the Theosophical Society in Adyar in April, BERLIN, GERMANY 3 together with reports and summaries of the UNTERLENGENHARDT, GERMANY 4 previous years of this campaign for justice. LONDON ENGLAND [1] 4 LONDON ENGLAND [2] 5 EDMONTON, CANADA 6 “Nothing is gained by worrying… You do not alter people, and… by being BRASILIA, DF, BRAZIL 7 anxious as to things, you put an occult SANTA CATARINA, BRAZIL 8 obstacle in the way of what you want done. BRASÍLIA, BRAZIL 9 FLORIANÓPOLIS, SC, BRAZIL 10 “It is better to acquire a lot of what is called carelessness by the world, but is PORTO ALEGRE, BRAZIL 11 in reality a calm reliance on the Law, BACKGROUND SO FAR and a doing of one’s own duty, satisfied that the results must be right, A SHORT 2007 REPORT ON LETTERS TO ADYAR 12 no matter what they may be.” THE 2006 ACTIONS AND RESULTS 12 William Q Judge A SHORT REPORT ON 2008 LETTERS TO ADYAR 11 The Aquarian Theosophist Vol. -

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Sociology Department, Faculty Publications Sociology, Department of 4-2-2016 “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons, and the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons Bosch, Brandon, "“Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films" (2016). Sociology Department, Faculty Publications. 287. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/sociologyfacpub/287 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Sociology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sociology Department, Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. VOLUME 17, ISSUE 1, PAGES 37–54 (2016) Criminology, Criminal Justice Law, & Society E-ISSN 2332-886X Available online at https://scholasticahq.com/criminology-criminal-justice-law-society/ “Why So Serious?” Threat, Authoritarianism, and Depictions of Crime, Law, and Order in Batman Films Brandon Bosch University of Nebraska-Lincoln A B S T R A C T A N D A R T I C L E I N F O R M A T I O N Drawing on research on authoritarianism, this study analyzes the relationship between levels of threat in society and representations of crime, law, and order in mass media, with a particular emphasis on the superhero genre. -

The Founding of the Theosophical Society

The Founding of the Theosophical Society by Walter A. Carrithers, Jr. [First published as the "Epilogue" to the 1975 abridged reprint of H.S. Olcott's 1875 Inaugural Address. This article was originally published under Mr. Carrither's pseudonym Adlai E. Waterman ] Writing in 1877, Madame H. P. Blavatsky first publicly disclosed something of her personal acquaintance with those Eastern Adept-Teachers, Brothers of the White Lodge, who since have become better known as the Mahatmas or Masters of Wisdom. In Isis Unveiled, her first book, she declared that the “practical blending of the visible with the invisible world” had found a “refuge” in “the chief lamaseries of Mongolia and Thibet,” and that there “the primitive science of magic” was “practiced to the utmost limits of intercourse allowed between man and ‘spirit.’ ” She urged the “pretended authorities of the West” to “go to the Brahmans and Lamaists of the far Orient, and respectfully ask them to impart the alphabet of true science.” This, she affirmed on the second page of her book, she herself had done: “It was while most anxious to solve these perplexing problems that we came into contact with certain men, endowed with such mysterious powers and such profound knowledge that we may truly designate them as the sages of the Orient. To their instructions we lent a ready ear.” It was five years later, in 1882, that one of these Great Sages, the Rajput Adept, Mahatma Morya, acknowledged responsibility for the initiative behind the confluence of circumstances that had made possible the founding of The Theosophical Society. -

Duplicity: Exploring the Many Faces of Gotham

Duplicity: Exploring the many faces of Gotham “And man shall be just that for the overman: a laughing stock or a painful embarrassment.” - Friedrich Nietzsche, Also Sprach Zarathustra The Dark Knight, Christopher Nolan’s follow up to 2005’s convention- busting Batman Begins, has just broken the earlier box office record set by Spiderman 3 with a massive opening weekend haul of $158 million. While the figures say much about this franchise’s impact on the popular imagination, critical reception has also been in a rare instance overwhelmingly concurrent. What is even more telling is that the old and new opening records were both set by superhero movies. Much has already been discussed in the media about the late Heath Ledger’s brave performance and how The Dark Knight is a gritty new template for all future comic-to-movie adaptations, so we won’t go into much more of that here. Instead, let’s take a hard and fast look at absolutes and motives: old, new, black, white and a few in between. The brutality of The Dark Knight is also the brutality of America post-9/11: the inevitable conflict of idealism and reality, a frustrating political comedy of errors, and a rueful Wodehouseian reconciliation of the improbable with the impossible. Even as the film’s convoluted and always engaging plot breaks down some preconceptions about the psychology of the powerful, others are renewed (at times without logical basis) – that politicians are corruptible, that heroes are intrinsically flawed, that what you cannot readily comprehend is evil incarnate – and it isn’t always clear if this is an attempt at subtle irony or a weary concession to formula. -

The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P

The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett The Early Days of Theosphy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett Theosophical Publishing House Ltd, London, 1922 NOTE [Page 5] Mr. Sinnett's literary Executor in arranging for the publication this volume is prompted to add a few words of explanation. There is naturally some diffidence experienced in placing before the public a posthumous MSS of personal reminiscences dealing in various instances with people still living. It would, however, be impossible to use the editorial blue pencil without destroying the historical value of the MSS. Mr. Sinnett's position and associations with the Theosophical Society together with his standing as an author in the Theosophical movement alike demand that his last writing should be published, and it is left to each reader to form his own judgment as to the value of the book in the light of his own study of the questions involved. Page 1 The Early Days of Theosophy in Europe by A.P. Sinnett CHAPTER - 1 - NO record could truly be called a History of the Theosophical Society if it concerned itself merely with events taking shape on the physical plane of life. From the first such events have been the result of activities on a higher plane; of steps taken by the unseen Powers presiding over human evolution, whose existence was unknown in the outer world when their great undertaking — the Theosophical Movement — was originally set on foot. To those known in the outer world as the Founders of the Theosophical Society — Madame Blavatsky and Colonel Olcott — the existence of these higher powers, The Brothers as they were called at first, was more or less imperfectly comprehended. -

Monday Evening Television

DIARIES AJAMA P THE ERNEST & FRANK WORTH Y MAR FRIENDS BETWEEN BIZARRO OOP ALLEY LEE EDISON OF MIND BRILLIANT Monday Evening Television 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 12:00 2 News at 6:00pm Entertainment To- Kevin Can Wait: Man With a 2 Broke Girls (N) The Odd Couple: I Scorpion: Bat Poop Crazy. The team 2 News at (10:37) The Late Show With Stephen (11:39) The Late Late Show With KUTV (N) (CC) night (N) (s) (CC) Hallow-We-Ain’t- Plan (N) (s) (CC) (s) (CC) (TV14) Kid, You Not. (N) investigates a bat population. (N) (s) 10:00pm (N) (CC) Colbert: Ruth Wilson; J.B. Smoove. James Corden: Harry Connick Jr.; Home. (N) (TVPG) (TVPG) (TVPG) (CC) (TV14) (N) (s) (TVPG) Alice Eve. (N) (s) (CC) (TV14) ABC 4 Utah News Inside Edition (N) Dancing With the Stars: Halloween-themed routines. (N Same-day Tape) (s) (9:01) All Access Nashville: Celebrat- ABC 4 Utah News (10:35) Jimmy Kimmel Live (N) (s) (11:37) Nightline (12:07) Access KTVX at 6pm (N) (s) (CC) (TVPG) (CC) (TVPG) ing the CMA Awards With Robin at 10pm (N) (CC) (TV14) (N) (CC) (TVG) Hollywood (N) (s) Roberts (N) (s) (CC) (CC) (TVPG) KSL 5 News at 6p KSL 5 News at The Voice: The Knockouts, Part 3. Artists perform for the coaches. (N) (s) (9:01) Timeless: The Alamo. The KSL 5 News at 10 (10:34) The Tonight Show Starring (11:37) Late Night With Seth Meyers: KSL (N) (CC) 6:30p (CC) (CC) (TVPG) team is stranded inside the Alamo. -

Batman, Screen Adaptation and Chaos - What the Archive Tells Us

This is a repository copy of Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94705/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Lyons, GF (2016) Batman, screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us. Journal of Screenwriting, 7 (1). pp. 45-63. ISSN 1759-7137 https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.7.1.45_1 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Batman: screen adaptation and chaos - what the archive tells us KEYWORDS Batman screen adaptation script development Warren Skaaren Sam Hamm Tim Burton ABSTRACT W B launch the Caped Crusader into his own blockbuster movie franchise were infamously fraught and turbulent. It took more than ten years of screenplay development, involving numerous writers, producers and executives, before Batman (1989) T B E tinued to rage over the material, and redrafting carried on throughout the shoot. -

Fortean Times 338

THE X-FILES car-crash politics jg ballard versus ronald reagan cave of the witches south america's magical murders they're back: is the truth still out there? phantom fares japan's ghostly cab passengers THE WORLD’S THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA WWW.FORTEANTiMES.cOM FORTEAN TiMES 338 chimaera cats • death by meteorite • flat earth rapper • ancient greek laptop WEIRDES NEWS T THE WORLD OF STRANGE PHENOMENA www.forteantimes.com ft338 march 2016 £4.25 THE SEcRET HiSTORy OF DAviD bOWiE • RETuRN OF THE x-FiLES • cAvE OF THE WiTcHES • AuTOMATic LEPREcHAuNSP • jAPAN'S GHOST ACE ODDITY from aliens to the occult: the strange fascinations of daVid b0Wie FA RES bogey beasts the shape-shifting monsters of british folklore mystery moggies on the trail of alien big MAR 2016 cats in deepest suffolk Fortean Times 338 strange days Japan’s phantom taxi fares, John Dee’s lost library, Indian claims death by meteorite, cretinous criminals, curious cats, Harry Price traduced, ancient Greek laptop, Flat Earth rapper, CONTENTS ghostly photobombs, bogey beasts – and much more. 05 THE CONSPIRASPHERE 23 MYTHCONCEPTIONS 05 EXTRA! EXTRA! 24 NECROLOG the world of strange phenomena 15 ALIEN ZOO 25 FAIRIES & FORTEANA 16 GHOSTWATCH 26 THE UFO FILES features COVER STORY 28 THE MAGE WHO SOLD THE WORLD From an early interest in UFOs and Aleister Crowley to fl irtations with Kabbalah and Nazi mysticism, David Bowie cultivated a number of esoteric interests over the years and embraced alien and occult imagery in his costumes, songs and videos. DEAN BALLINGER explores the fortean aspects and influences of the late musician’s career. -

Redeveloping the Distillery District, Toronto

Place Differentiation: Redeveloping the Distillery District, Toronto by Vanessa Kirsty Mathews A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Geography University of Toronto © Copyright by Vanessa Kirsty Mathews 2010 Place Differentiation: Redeveloping the Distillery District, Toronto Doctor of Philosophy Vanessa Kirsty Mathews, 2010 Department of Geography University of Toronto Abstract What role does place differentiation play in contemporary urban redevelopment processes, and how is it constructed, practiced, and governed? Under heightened forms of interurban competition fueled by processes of globalization, there is a desire by place- makers to construct and market a unique sense of place. While there is consensus that place promotion plays a role in reconstructing landscapes, how place differentiation operates – and can be operationalized – in processes of urban redevelopment is under- theorized in the literature. In this thesis, I produce a typology of four strategies of differentiation – negation, coherence, residue, multiplicity – which reside within capital transformations and which require activation by a set of social actors. I situate these ideas via an examination of the redevelopment of the Gooderham and Worts distillery, renamed the Distillery District, which opened to the public in 2003. Under the direction of the private sector, the site was transformed from a space of alcohol production to a space of cultural consumption. The developers used a two pronged approach for the site‟s redevelopment: historic preservation and arts-led regeneration. Using a mixed method approach including textual analysis, in-depth interviews, visual analysis, and site observation, I examine the strategies used to market the Distillery as a distinct place, and the effects of this marketing strategy on the valuation of art, history, and space. -

Hawkman in the Bronze Age!

HAWKMAN IN THE BRONZE AGE! July 2017 No.97 ™ $8.95 Hawkman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. BIRD PEOPLE ISSUE: Hawkworld! Hawk and Dove! Nightwing! Penguin! Blue Falcon! Condorman! featuring Dixon • Howell • Isabella • Kesel • Liefeld McDaniel • Starlin • Truman & more! 1 82658 00097 4 Volume 1, Number 97 July 2017 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST George Pérez (Commissioned illustration from the collection of Aric Shapiro.) COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Alter Ego Karl Kesel Jim Amash Rob Liefeld Mike Baron Tom Lyle Alan Brennert Andy Mangels Marc Buxton Scott McDaniel John Byrne Dan Mishkin BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury ............................2 Oswald Cobblepot Graham Nolan Greg Crosby Dennis O’Neil FLASHBACK: Hawkman in the Bronze Age ...............................3 DC Comics John Ostrander Joel Davidson George Pérez From guest-shots to a Shadow War, the Winged Wonder’s ’70s and ’80s appearances Teresa R. Davidson Todd Reis Chuck Dixon Bob Rozakis ONE-HIT WONDERS: DC Comics Presents #37: Hawkgirl’s First Solo Flight .......21 Justin Francoeur Brenda Rubin A gander at the Superman/Hawkgirl team-up by Jim Starlin and Roy Thomas (DCinthe80s.com) Bart Sears José Luís García-López Aric Shapiro Hawkman TM & © DC Comics. Joe Giella Steve Skeates PRO2PRO ROUNDTABLE: Exploring Hawkworld ...........................23 Mike Gold Anthony Snyder The post-Crisis version of Hawkman, with Timothy Truman, Mike Gold, John Ostrander, and Grand Comics Jim Starlin Graham Nolan Database Bryan D. Stroud Alan Grant Roy Thomas Robert Greenberger Steven Thompson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Penguin, Gotham’s Gentleman of Crime .......31 Mike Grell Titans Tower Numerous creators survey the history of the Man of a Thousand Umbrellas Greg Guler (titanstower.com) Jack C. -

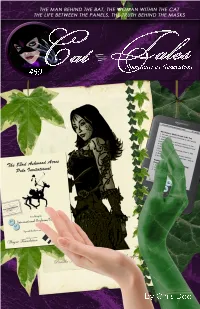

Spontaneous Generation

by Chris Dee CAT-TALES SSPONTANEOUS GGENERATION CAT-TALES SSPONTANEOUS GGENERATION By Chris Dee COPYRIGHT © 2015 BY CHRIS DEE ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. BATMAN, CATWOMAN, GOTHAM CITY, ET AL CREATED BY BOB KANE, PROPERTY OF DC ENTERTAINMENT, USED WITHOUT PERMISSION SPONTANEOUS GENERATION Prologue: Ivy's Song Weakness. If there was one thing that made her physically ill, it was weakness. Nature was not weak. Nature was the ultimate power. What could man make that Nature could not destroy? Their fleshy bodies, their cities, their pitiful notions of achievement? What was a church compared to a forest? A painting compared to a mountain, a symphony next to a flower… Well, actually, she liked music. Even her plants liked music. Mozart in particular. And there was nothing in Nature to compare it to. The mathematical underpinnings of music were absolutely man-made, and it had to be said, it was… beautiful. A THOUGHT THAT MADE HER WANT TO SCREAM! Beautiful belonged to Nature. It belonged to Flowers. It was hers, and this filthy animal, masculine, homo sapien, civilized, plant-eating THING had made something that was wholly theirs, wholly unique, and wholly beautiful. JUST HAVING THE THOUGHT MADE HER WANT TO RIP HER HAIR OUT BY THE ROOT! It was so weak. Pamela’s little thoughts and feelings. As the living embodiment of the Goddess Lifeforce, Poison Ivy rebelled at the idea of hating any part of herself, but that, that… Pamela had become such a burden. People made something beautiful. It was disgusting. But now she had that thought in her head, and it was all because of that part of herself that, for lack of a better term, she called Pam.