Visit the National Academies Press Online, the Authoritative Source for All Books from the National Academy of Sciences, The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historic Costuming Presented by Jill Harrison

Historic Southern Indiana Interpretation Workshop, March 2-4, 1998 Historic Costuming Presented By Jill Harrison IMPRESSIONS Each of us makes an impression before ever saying a word. We size up visitors all the time, anticipating behavior from their age, clothing, and demeanor. What do they think of interpreters, disguised as we are in the threads of another time? While stressing the importance of historically accurate costuming (outfits) and accoutrements for first- person interpreters, there are many reasons compromises are made - perhaps a tight budget or lack of skilled construction personnel. Items such as shoes and eyeglasses are usually a sticking point when assembling a truly accurate outfit. It has been suggested that when visitors spot inaccurate details, interpreter credibility is downgraded and visitors launch into a frame of mind to find other inaccuracies. This may be true of visitors who are historical reenactors, buffs, or other interpreters. Most visitors, though, lack the heightened awareness to recognize the difference between authentic period detailing and the less-than-perfect substitutions. But everyone will notice a wristwatch, sunglasses, or tennis shoes. We have a responsibility to the public not to misrepresent the past; otherwise we are not preserving history but instead creating our own fiction and calling it the truth. Realistically, the appearance of the interpreter, our information base, our techniques, and our environment all affect the first-person experience. Historically accurate costuming perfection is laudable and reinforces academic credence. The minute details can be a springboard to important educational concepts; but the outfit is not the linchpin on which successful interpretation hangs. -

MICROFIBER & MORE LLC Healthcare Systems Distributed by Microfi Ber & More LLC

{DUSTBUNNIESBEWARE} MICROFIBER & MORE LLC Healthcare Systems Distributed by Microfi ber & More LLC SBCART CLEANING SYSTEM SEALING BUCKET PRE-TREAT MOP SYSTEM reduce cross contamination 1.5 gallon of water cleans 15,000 sq. feet 1-2 ounce chemical cleans 15,000 sq. feet no dirty water to dispose no r lling mop buckets launder mops 500 times reduce employee injury reduce absenteeism DUSTING & SURFACES CLEANING overhead dusting white boards counters computer screens RESTROOM FIXTURES, MIRRORS & SHOWERS bathroom xtures mirrors showers FLOORS, WALLS & BASEBOARDS bathroom oors walls baseboards patient room oors MICRO101 HealthCareSaleSheet.FA.indd 1 1/9/10 5:37 PM MICRO103 Catalog_paths.FA.indd 3 1/11/10 2:54 PM MICRO103 Catalog_paths.FA.indd 4 1/11/10 2:54 PM Page 5 Education with bleeds.pdf 1 1/9/13 4:01 PM Education & Office Systems Distributed by Microfi ber & More LLC DUAL COMPARTMENT MOP BUCKET CHART 7 QUICK & EASY STEPS TO A CLEANER AND HEALTHIER ENVIRONMENT. FILL BUCKET MOP SURFACE Front compartment with Mop hard surface areas. 3 gallons of cleaning solution. Use mop until dry. Fill rear compartment with 1 gallon of clear water. STEP 1 STEP 5 INSTALL MOP RINSE MOP Install tab mop on frame and Rinse mop in rear rinse slide tabs through opening compartment. C and clamp down. M STEP 2 STEP 6 Y CM MY CY CHARGE MOP WRING MOP Charge mop in front com- Recharge mop in clean CMY partment with solution. K STEP 7 STEP 3 WRING MOP Wring out excess solution from mop making sure correct moisture. -

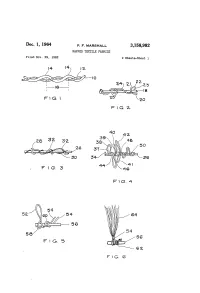

Dec. 1, 1964 P, F, MARSHA 3,158,982 NAPPED TEXTILE FABRICS Filed Nov

Dec. 1, 1964 P, F, MARSHA 3,158,982 NAPPED TEXTILE FABRICS Filed Nov. 29, 1962 2 Sheets-Sheet l F G. 4 Dec. 1, 1964 P, F, MARSHALL 3,158,982 NAPPED TEXTILE FABRICS Filled Nov. 29, 1962 2 Sheets-Sheet 2 3,158,982 United States Patent Office Patented Dec. 1, 1964 2 It is an object of this invention to provide a napped - 3,158,982 fabric comprising wrapped yarns in which the nap is of NAPPED TEXTELEFABRICS exceptional length, is firmly anchored to the base fabric, Preston F. Marshal, Walpole, Mass, assignor to The and is relatively free from lint and broken fibers. Kenda Company, Boston, Mass, a corporation of 5 It is a further object of this invention to provide a Massachusetts -- . - napped fabric comprising yarns wrapped with a plurality M Fied Nov. 29, 1962, Ser. No. 240,942 of strands which comprise filaments of different stiffness, 7 Claims. (C. 57-140) to effect a mixed filamentary nap. This invention relates to napped textile fabrics, and The invention will be more clearly understood in con more particularly to a textile fabric in which the nap is O nection with the accompanying drawings, in which: of superior length, is substantially lint-free, and tightly FIGURE 1 represents a conventional plied yarn, of anchored into the fabric. The present application is a two ends twisted together. continuation-in-part of my copending application Serial FIGURE 2 represents a wrapped yarn of the type Number 212,922, filed July 17, 1962, which is in turn a known as a loop yarn. -

FABRICS/ DYING Dictionary

FABRICS/ DYING dictionary ACRYLIC BABYCORD Acrylic fabric is a manufactured fiber with a soft wool-like feel and Babycord is a ribcord fabric with a very small and thin rib line. The an uneven finish. It is used widely in knits as the fabric has the same fabric is often lighter and softer than normal or corduroy fabric. It is cozy look as wool. Acrylic fabric is favored for a variety of reasons very soft and comfortable, and is often made in a stretch quality. it is warm, quite soft, holds color well, is both stain and wrinkle resistant and it doesn’t itch. These qualities make acrylic a great BLEND substitute for wool. A blend fabric or yarn is made up of more than one fibre. In the yarn, two or more different types of fibres are used to form the yarn. ALPACA Blends are used to create a more comfortable fabric with a softer Alpaca wool comes from a South American animal that roams the feel. A good example is a cotton/wool blend; the mixture of cotton mountain slopes of Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and Chile. The fleece and wool will prevent the fabric from being excessively warm and from an alpaca is similar to wool or mohair, but is softer, silkier, and will make the fabric softer to the skin. warmer. Because alpaca wool takes much longer to grow it is often more expensive and exclusive. However, garments made from this BOUCLE fabric are stronger and more comfortable. The term boucle is derived from the French word boucle, which literally means “to curl”. -

![[Protec 1000 G Is a Decorative, Stipple, Gloss Epoxy Coating for Cast-In-Place Concrete Floors & Walls]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9277/protec-1000-g-is-a-decorative-stipple-gloss-epoxy-coating-for-cast-in-place-concrete-floors-walls-1239277.webp)

[Protec 1000 G Is a Decorative, Stipple, Gloss Epoxy Coating for Cast-In-Place Concrete Floors & Walls]

Protective Industrial Polymers - USA 09 96 13 Manufacturer’s Specification ANTIMICROBIAL GLASS CLOTH-REINFORCED SYSTEM August 13, 2015 This specification covers BrewSpec GlassMat Antimicrobial Glass Cloth-Reinforced System, a high-performance antimicrobial system consisting of an antimicrobial vertical-substrate concrete pretreatment, an antimicrobial block-filler, and antimicrobial flexible hybrid basecoat reinforced with glass cloth mat. A 2nd application of the flexible hybrid basecoat is applied, followed by an application of an antimicrobial glass and fiber-reinforced epoxy build coat. This base is top coated with a high-performance antimicrobial urethane. This smooth, clothe reinforced wall system is easy to wash and is suited for use in areas where superior chemical resistance, durability and UV-stability are crucial. 1.00 GENERAL 1.01 SECTION INCLUDES A. Preparation of concrete or block substrate B. Apply antimicrobial concrete/block pretreatment C. Apply antimicrobial concrete/block filler D. Apply antimicrobial hybrid basecoat E. Apply glass cloth mat F. Apply antimicrobial hybrid basecoat G. Apply antimicrobial glass and fiber-reinforced epoxy coating H. Apply antimicrobial urethane topcoat Specifier Notes: Edit the following list as required by the project. List other sections with work directly related to the floor coating. 1.02 RELATED SECTIONS A. Section 03 30 00 – Cast-In-Place Concrete: [existing or] new slab. B. Section 03 35 00 – Concrete Finishing: specific chemicals on slab. C. Section 03 39 00 - Concrete Curing D. Section 03 01 00 – Concrete Rehabilitation 1.04 REFERENCES STANDARDS A. For reference standards tests & results refer to Manufactures Product Data Sheets 1.05 ADMINISTRATIVE REQUIRMENTS A. Pre installation meeting call if needed. -

INSTALLATION PROCEDURE ® 505/510 Coroline Ceilcote

INSTALLATION PROCEDURE Ceilcote® 505/510 Coroline R e i n f o r c e d T r o w e l A p p l i e d E p o x y L i n i n g / T o p p i n g Description For Application: Installation information contained in this procedure is as specific • Shears or utility knife for cutting glass cloth/mat as possible but cannot cover all variations in field conditions. If Plaster or cement finishing trowel (generally 4“x12“) anticipated conditions do not permit following these guidelines, • do not hesitate to call your CEILCOTE Representative. • Marginal trowels 2“ x 5“ or 2“ x 8“ • Wallpaper brush (for dry pressing glass cloth/mat before CEILCOTE 505 Coroline is a silica filled system. CEILCOTE S-1 saturating) powder is used as the filler for this standard system. • Smoothing brush – good grade horsehair, nylon, and/or short nap mohair paint roller (for topcoat) CEILCOTE 505AR Coroline is an abrasion resistant system. CEILCOTE S-9AR powder is used as the filler for abrasion • Paint roller covers (short 3/8“ nap mohair or equivalent) and resistance. frames • Steel or aluminum ribbed roller if using mat instead of cloth CEILCOTE 505BR Coroline Basecoat/Saturant is optional and • 1 gal (3.78 liter) pail for smoothing liquid (T-420) recommended when surface conditions are exposed to high • 1 gal (3.78 liter) pail for cleaning solvent humidity and/or low temperature, creating the potential condition • Clean Pails -3 or 5 gal (minimum 5 required for mixing, for excess amine blush, common with outside applications. -

Trauma-Informed Practice Guide

Trauma-Informed Practice Guide ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Guide was developed on behalf of the BC Provincial Mental Health and Substance Use Planning Council in consultation with researchers, practitioners and health system planners across British Columbia. Cristine Urquhart and Fran Jasiura of Change Talk Associates prepared the initial draft of this guide. The further development of the Guide, as well as the consultation process, has been led by the TIP Project Team and supported through the advice, input and editorial suggestions of the TIP Advisory Committee. TIP Project Team Emily Arthur, BC Ministry of Health, Mental Health and Substance Use Branch Amanda Seymour, Formerly with BC Ministry of Health, Mental Health and Substance Use Branch Michelle Dartnall, Vancouver Island Health Authority, Youth and Family Substance Use Services Paula Beltgens, Vancouver Island Health Authority, Youth and Family Substance Use Services Nancy Poole, BC Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health (BCCEWH) Diane Smylie, BC Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health (BCCEWH) Naomi North, BC Ministry of Health, Mental Health & Substance Use Branch (until February 2012) Rose Schmidt, BC Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health (BCCEWH) Consulting Psychologist Elizabeth Hartney, Ph.D., R.Psych., BC Ministry of Health , Mental Health and Substance Use Branch TIP Advisory Committee Evan Adams, BC Ministry of Health, Office of the Provincial Health Officer Gayle Read, BC Ministry of Children and Family Development Shabna Ali, BC Society of Transition Houses Rod Macdonald, -

Napping of Cotton Fabrics

TECHNICAL BULLETIN 6399 Weston Parkway, Cary, North Carolina, 27513 • Telephone (919) 678-2220 TRI 3006 NAPPING OF COTTON FABRICS © 1994 Cotton Incorporated. All rights reserved; America’s Cotton Producers and Importers. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION............................................................................................... 1 DEFINITION OF TERMS ................................................................................. 1 HISTORY OF NAPPING................................................................................... 1 NAPPING EQUIPMENT DOUBLE ACTION NAPPER......................................................................... 2 KNIT FABRIC NAPPER ................................................................................ 3 SINGLE ACTION NAPPER........................................................................... 3 COMBINATION NAPPERS .......................................................................... 4 ZERO POINT ...................................................................................................... 4 NAPPER WIRE................................................................................................... 5 SHEARING ......................................................................................................... 7 FABRIC CONSTRUCTION.............................................................................. 7 FIBER LUBRICATION ..................................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION Classic cotton fabrics -

Polishing Pad Selection Guide

Polishing Pad Selection Guide www.metallographic.com Metal Mesh Cloth is a wire mesh material used for coarse and intermediate (15 µm or 30 µm diamond) lapping / polishing. The texture and spacing of the wire mesh allows for the abrasive to become semi-fixed; thus offering the advantage of increased stock removal, while minimizing damage. It is particularly useful for ceramics and composites. POLYPAD™ Polishing Cloth is a synthetic polyester polishing pad which has a similar polishing action to a nylon pad, with the exception that it is more durable. It is used for the intermediate diamond polishing steps using 3,6,9 or 15 µm polycrystalline diamond. TEXPAN™ Polishing Cloth is the most commonly used low napped polymer polishing pad. Its primary applications are as an intermediate polishing pad (3,6 or 9 µm diamond) for metals and as both an intermediate and final polishing pad for hard ceramics and composites (1, 3 or 6 µm diamond). Black Chem™ Polishing Cloth is a porometric polymer pad which has a low nap but behaves as an intermediate polishing pad with a performance between TEXPAN™ pad and POLYPAD™ cloth. It is useful for materials such as silicon or glass which are too brittle for TEXPAN™ pad and too hard for POLYPAD™ cloth. DACRON® Polishing Cloth is a low napped polishing pad for polishing primarily with 1-15 micron diamond abrasives. The DACRON pad is the most popular intermediate polishing pad in Europe NEW! and is used mostly for polishing metals. Note: DACRON is a registered trade name of DUPONT Corporation. TRICOTE™ Polishing Cloth - this is a tightly woven suede final polishing pad for metals and polymers. -

The Rise, Expansion, and Decline of the Italian Wool-Based Cloth

The Rise, Expansion, and Decline of the Italian Wool-Based Cloth Industries, 1100–1730: A Study in International Competition, Transaction Costs, and Comparative Advantage John H. Munro University of Toronto Introduction: Italy and Textiles in the European Economy 1 In the history of the West European economy from the twelfth to the eighteenth centuries, wool-based textiles constituted the single most important manufactured commodity to enter both regional and interna- tional trade. For this reason, such textiles proved to be vitally important for Italian economic development and for Italy’s economic preeminence during many of these centuries, especially up to the sixteenth. Italy was, in fact, one of the three most important regions that supplied good- to high-quality wool-based textiles to much of Christian Europe and to the Islamic world in the Mediterranean basin and the Near East during the I wish to thank the anonymous referees, the editor, and Prof. Samuel Cohen Jr. for their most valuable advice in revising this article. 1 An earlier and much shorter version of this study was published as John Munro, “I panni di lana,” in Il Rinascimento italiano e l’Europa, ed. Luca Ramin, vol. 4: Commercio e cultura mercantile, ed. Franco Franceschi, Richard Goldthwaite, and Reinhold Mueller (Treviso, 2007), 105–41. This version is based on a considerable amount of additional research and an elaboration of my key arguments. Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History, 3rd Series, Vol. 9 (2012) Copyright © 2012 AMS Press, Inc. All rights reserved. 46 Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History medieval and early modern eras. -

Baize Lisa Cooperman

For immediate release A.I.R. Baize Lisa Cooperman August 3 – August 20, 2017 Opening Reception: Thursday, August 3rd, 6 – 8pm A.I.R. Gallery is pleased to announce Baize, an exhibition by Alumni Artist Lisa Cooperman. In her second solo exhibition at A.I.R., Cooperman will show a new body of work featuring textile sculptures inspired by life in California’s Central Valley. Cooperman’s work delves into the complexities of Stockton, an historic river delta town and epicenter of pioneer mythologizing, exploitive labor practices and environmental malfeasance. Stockton’s clamorous narratives inform this series of abstracted wall-hung pieces. Working in the make-do tradition of the city, she uses found and recycled materials selected both for their formal appeal and historic association. Lisa Cooperman, Fek, 2016, mixed media. Baize is a thick woolen fabric traditionally found tacked to interior doors to mule the sounds of domestic activity. Later used on gaming tables, its fuzzy nap slowed the roll of cards and pool balls. The woolen tablecloths at the material core of this exhibition were rescued from the dumpster at the Haggin Museum, where Cooperman worked. For decades these tablecloths were used at the annual card parties of the San Joaquin Chapter of the Ladies Auxiliary of California Pioneers. In Baize they have been remade for wall and floor - cut, sewn, bunched and bundled - and enhanced with other materials including sequins , buttons, and onion bags. Their new forms are an exploration of imaginary conversations and a nod to the labor that enables leisure. Cooperman is the University Curator at the University of the Pacific and was previously the Curator of Education at the Haggin Museum. -

Interesting Textures and a Very Soft Hand Makes Chenille

The Thread Unraveling the Mysteries of Fibers, Fabrics and Floor Coverings LIVING WITH RAYON… Natural Shading And Nap Distortion Rayon Resurgence! pulp, bamboo, cotton trash or If the fibers are oriented away Rayon was the first other natural fiber by-products, from your line of sight, the area manufactured fiber and adding chemicals to break them will appear to have lightened. variations of it have been down, and then forcing the Conversely if the fibers are marketed since the mid 1800’s, mixture through spinnerets to pointing toward you, the area but it wasn’t officially named create a lustrous fiber that is will appear darker. With rayon until 1924. It is the oldest neither a true synthetic nor a continued use, the shading production fiber and for many natural fiber. Rayon is a semi- becomes more noticeable. years was out of favor with synthetic or artificial fiber known manufacturers because so as a manmade cellulosic fiber. many other new fibers were being invented. However, over the past few years, textile The Natural Shading producers have been using of Rayon much more rayon in both Because rayon is now being clothing and home furnishings used so frequently to make fabrics. velvets, chenilles and pile floor coverings, this article will focus Sometimes rayon is hard for on helping consumers to consumers to recognize understand rayon and what to because it has many names – expect when it is used as an This type of shading generally Bemberg, Viscose, upholstery fabric on sofas, does not distract from the Cuprammonium and Art Silk, chair, area rugs and carpet.