Atheism for Lent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Communicator 1

February, 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Communicator 1. Search for New February, 2017 Lead 2. a. New Lead Spirit-Guided Search for the New Lead cont’d. Minister b. February By Rev. Nayiri Karjian, Interim Lead Minister Worship [email protected] c. Shrove Tuesday “How long will you be here?” “How long will the search last?” These are some of the questions 3. a. Organist I am asked as many of you wonder about the search process. I am glad to share how the process b. Soup Fundraiser usually unfolds. c. Peanut Butter The Search Committee currently is gathering information from you, the congregation, to compile 4. Youth & Adult the Church Profile, a 20 page document that introduces our congregation to an interested Ministry candidate. Their goal is to complete the profile by the end of February. 5. The Forum The next step is to activate the listing in the UCC Ministry Opportunities 6. KC Worship http://www.ucc.org/ucc_ministry_opportunities 7. Financial Ministry or exact page http://oppsearch.ucc.org/web/searchresult.aspx?q=jobposition&v=Senior_Pastor 8. JWW Lectureship Once the listing is activated, interested candidates will send their profile/professional resume to our Search Committee via the Rocky Mountain Conference UCC. 9. Mission Giving & Outreach The Search Committee reads the profiles and responds to the candidates. They check candidates’ 10. A Peek in the Past online presence, listening to sermons or reading them, checking Facebook, and so on. They also send candidates information about our church. All communication is usually done electronically. 11. Congregational Life The committee discerns the candidates who are a good match and contacts them for interviews, usually set up via skype. -

The Day of the Lord Will Come Like a Thief

THE DAY OF THE LORD WILL COME LIKE A THIEF 2 Peter 3:1-18 Key Verse: 3:10 “But the day of the Lord will come like a thief. The heavens will disappear with a roar; the elements will be destroyed by fire, and the earth and everything done in it will be laid bare.” The world we live in is overflowing with bad news. Recently we heard about sudden natural disasters—like the mudslides that buried many people in Washington state. And then there have been acts of violence, such as the stabbing of 20 people in a Pennsylvania school, and the fatal shooting of three soldiers in Fort Hood, Texas. There is a threat of war in Ukraine. While these things are happening, many people bury their heads in virtual reality, going from one petty pleasure to another, lost in aimless distractions. Life seems to be a joke. A person is here today and gone tomorrow. The world seems to be a jungle full of accidents and random violence. But this is not new. Where is justice? Where is God? Does God intervene in the universe? Hebrews 1:3 says that Jesus sustains all things by his powerful word. The world could not continue for even one more day without God’s intervention. These days we see many signs of the end of the age. Yet, God is always at work in the midst of them. Jesus said, “My Father is always at his work to this very day, and I too am working” (Jn 5:17). -

A Feminist Analysis of the Emerging Church: Toward Radical Participation in the Organic, Relational, and Inclusive Body of Christ

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Boston University Institutional Repository (OpenBU) Boston University OpenBU http://open.bu.edu Theses & Dissertations Boston University Theses & Dissertations 2015 A feminist analysis of the Emerging Church: toward radical participation in the organic, relational, and inclusive body of Christ https://hdl.handle.net/2144/16295 Boston University BOSTON UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY Dissertation A FEMINIST ANALYSIS OF THE EMERGING CHURCH: TOWARD RADICAL PARTICIPATION IN THE ORGANIC, RELATIONAL, AND INCLUSIVE BODY OF CHRIST by XOCHITL ALVIZO B.A., University of Southern California, 2001 M.Div., Boston University School of Theology, 2007 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 © 2015 XOCHITL ALVIZO All rights reserved Approved by First Reader _________________________________________________________ Bryan Stone, Ph.D. Associate Dean for Academic Affairs; E. Stanley Jones Professor of Evangelism Second Reader _________________________________________________________ Shelly Rambo, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Theology Now when along the way, I paused nostalgically before a large, closed-to-women door of patriarchal religion with its unexamined symbols, something deep within me rises to cry out: “Keep traveling, Sister! Keep traveling! The road is far from finished.” There is no road ahead. We make the road as we go… – Nelle Morton DEDICATION To my Goddess babies – long may you Rage! v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation has always been a work carried out en conjunto. I am most grateful to Bryan Stone who has been a mentor and a friend long before this dissertation was ever imagined. His encouragement and support have made all the difference to me. -

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio

Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 12 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 12:00:10 AM Hold Me Jesus Big Daddy Weave Every Time I Breathe (2006) 12:03:59 AM Do Something Matthew West Into The Light 12:07:59 AM Wonderful Merciful Savior Selah Press On (2001) 12:12:20 AM Jesus Loves Me Chris Tomlin Love Ran Red (2014) 12:15:45 AM Crown Him With Many Crowns Michael W. Smith/Anointed I'll Lead You Home (1995) 12:21:51 AM Gloria Todd Agnew Need (2009) 12:24:36 AM Glory Phil Wickham The Ascension (2013) 12:27:47 AM Do Everything Steven Curtis Chapman Do Everything (2011) 12:31:29 AM O Love Of God Laura Story God Of Every Story (2013) 12:34:26 AM Hear My Worship Jaime Jamgochian Reason To Live (2006) 12:37:45 AM Broken Together Casting Crowns Thrive (2014) 12:42:04 AM Love Has Come Mark Schultz Come Alive (2009) 12:45:49 AM Reach Beyond Phil Stacey/Chris August Single (2015) 12:51:46 AM He Knows Your Name Denver & the Mile High Orches EP 12:55:16 AM More Than Conquerors Rend Collective The Art Of Celebration (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 1 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 1:00:08 AM You Are My All In All Nichole Nordeman WOW Worship: Yellow (2003) 1:03:59 AM How Can It Be Lauren Daigle How Can It Be (2014) 1:08:12 AM Truth Calvin Nowell Start Somewhere 1:11:57 AM The One Aaron Shust Morning Rises (2013) 1:15:52 AM Great Is Thy Faithfulness Avalon Faith: A Hymns Collection (2006) 1:21:50 AM Beyond Me Toby Mac TBA (2015) 1:25:02 AM Jesus, You Are Beautiful Cece Winans Throne Room 1:29:53 AM No Turning Back Brandon Heath TBA (2015) 1:32:59 AM My God Point of Grace Steady On 1:37:28 AM Let Them See You JJ Weeks Band All Over The World (2009) 1:40:46 AM Yours Steven Curtis Chapman This Moment 1:45:28 AM Burn Bright Natalie Grant Hurricane (2013) 1:51:42 AM Indescribable Chris Tomlin Arriving (2004) 1:55:27 AM Made New Lincoln Brewster Oxygen (2014) Praise & Worship from Moody Radio 04/28/15 Tuesday 2 A (CT) Air Time (CT) Title Artist Album 2:00:09 AM Beautiful MercyMe The Generous Mr. -

F : Iwjfv, Lllreaspr of C$E Department of English

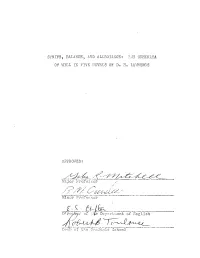

STRIFE, BALANCE, A WD ALLEGIANCE: '11,m SCHEMATA OF WILL IK FIVE NOVELS OF D. H. XAvJRENCK APPROVED: Ma j ox- P r of 0 3 s or / Minor P r of e r> s or f : IWJfv, lllreaSpr of c$e Department of English De?m of the Graduate School STRIFE, BALANCE, AND ALLEGIANCE: THE SCHEMATA OF WILL IN FIVE NOVELS OF D. H. LAWRENCE THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Teresa Monahan Fiddes, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1968 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. D. H. LAWRENCE: THE HERITAGE OF THE IRRATIONAL 1 II. THE NORDIC AND AFRICAN CONSCIOUSNESS: THE WILLS TO NULLITY 9 III. THE THEORY OF BALANCE: A GOOD TIGHT PUNT . 1*1 IV. CONTACT OF THE LEADER: PERSONAL AND COSMIC. 70 BIBLIOGRAPHY 92 iii CHAPTER I D. H. LAWRENCE: THE HERITAGE OF THE IRRATIONAL 125 "The mysteries practiced among men are unholy mysteries." 126 "And they pray to these images, as if one "were to talk •with a man's house, knowing not what gods or heroes are." Heraclitus D. H. Lawrence made the final break through the mask of Victorian prudery to gain a full conception of man and his role in the universe. His principal emphasis is on the restoration of man's conception of himsel£---a^.jinimal, an animal capable of conceptualizing, but essentially animal all the same. In attempting to restore man to the mindless state of irrational animism, Lawrence did away with the con- ventional idea of man as the perfection of God's created universe. -

3.NAPTS Bulletin.38.3.JR

Bulletin The North American Paul Tillich Society Volume XXXVIII, Number 3 Summer 2012 Editor: Frederick J. Parrella, Secretary-Treasurer Religious Studies Department, Santa Clara University Kenna Hall, Suite 300, Room H, Santa Clara, California 95053 Associate Editor: Jonathan Rothchild, Loyola Marymount University Assistant to the Editor: Vicky Gonzalez, Santa Clara University Production Assistant: Alicia Calcutt Telephone: 408.554.4714/ 408.554.4547 FAX: 408.554.2387 Email: [email protected] Website: www.NAPTS.org/ Webmeister: Michael Burch, San Raphael, California _________________________________________________________________________ Membership dues for 2012 are now payable: 50 USD regular, 20 USD student. Please print out or tear off the last page and send your check to: Professor Fre- derick J. Parrella, Religious Studies Dept./ Santa Clara University/ 500 East El Camino Real/ Santa Clara, California 95053. Thank you! In this issue: A Word about Dues (above) New Publications and Corrigendum “Differential Thinking and the Possibility of Faith-Knowledge: Tillich and Kierkegaard between Negative and Positive Philosophy” by Jari Ristiniemi “The Courage to Be (tray): An Emerging Conversation between Paul Tillich and Peter Rollins” by Carl-Eric Gentes “Can There Be a Theology of Disenchantment? Unbinding the Nihil in Tillich” by Thomas A. James “Tillich and Ontotheology: On the Fidelity of Betrayal” by J. Blake Huggins New Publications • Tillich, Paul. On the Boundary. An Autobiographi- cal Sketch. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock, 2011. ipf and Stock has recently re-issued three of New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1966. This W Paul Tillich’s important works. This is a great work, with some revisions, first appeared as the first service to Tillich scholars and new students of Til- chapter of The Interpretation of History, 3–73. -

Kappale Artisti

14.7.2020 Suomen suosituin karaokepalvelu ammattikäyttöön Kappale Artisti #1 Nelly #1 Crush Garbage #NAME Ednita Nazario #Selˆe The Chainsmokers #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat Justin Bieber #thatPOWER Will.i.am Feat. Justin Bieber (Baby I've Got You) On My Mind Powderˆnger (Barry) Islands In The Stream Comic Relief (Call Me) Number One The Tremeloes (Can't Start) Giving You Up Kylie Minogue (Doo Wop) That Thing Lauren Hill (Every Time I Turn Around) Back In Love Again LTD (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Brandy (Everything I Do) I Do It For You Bryan Adams (Hey Won't You Play) Another Somebody Done Somebody Wrong Song B. J. Thomas (How Does It Feel To Be) On Top Of The W England United (I Am Not A) Robot Marina & The Diamonds (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction The Rolling Stones (I Could Only) Whisper Your Name Harry Connick, Jr (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew (If Paradise Is) Half As Nice Amen Corner (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Shania Twain (I'll Never Be) Maria Magdalena Sandra (It Looks Like) I'll Never Fall In Love Again Tom Jones (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life Bill Medley-Jennifer Warnes (I've Had) The Time Of My Life (Duet) Bill Medley & Jennifer Warnes (Just Like) Romeo And Juliet The Re˜ections (Just Like) Starting Over John Lennon (Marie's The Name) Of His Latest Flame Elvis Presley (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Elvis Presley (Reach Up For The) Sunrise Duran Duran (Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty KC And The Sunshine Band (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay Otis Redding (Theme From) New York, New York Frank Sinatra (They Long To Be) Close To You Carpenters (We're Gonna) Rock Around The Clock Bill Haley & His Comets (Where Do I Begin) Love Story Andy Williams (You Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears (You Gotta) Fight For Your Right (To Party!) The Beastie Boys 1+1 (One Plus One) Beyonce 1000 Coeurs Debout Star Academie 2009 1000 Miles H.E.A.T. -

Why Me Lord.P7

This book is designed for your personal reading pleasure and profit. It is also designed for group study. A leader’s guide with helps and hints for teachers and visual aids (Victor Multiuse Transparency Masters) is available from your local bookstore or from the publisher. Fifth printing, 1987 Most of the Scripture quotations in this book are from the King James Version of the Bible (KJV). Other quotations are from the Holy Bible: New International Version (NIV), © 1973, 1978, 1984, International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Bible Publishers; the New American Standard Bible (NASB), © the Lockman Foundation, 1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977. Used by permission. Recommended Dewey Decimal Classification: 241.1 Suggested subject heading: THE WILL OF GOD IN CRISES Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 80-52947 ISBN: 0-89693-007-6 © 1981 by SP Publications, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America VICTOR BOOKS A division of SP Publications, Inc. Wheaton, Illinois 60187 Dedication To the women in my life: Mary, my mother Emma, Pat, and Lillian, my sisters Cathy, my wife Lori, my daughter Gerrie, my editor Gloria, my secretary Anita, my typist Contents Preface 9 Part I—How to Live 1 Why? Why? Why? 13 2 The Choice Is Yours 22 3Triumph Out of Tragedy 28 Part II—How to Die 4 Life after All 39 5 Am I Normal? 45 6 Broken Hearts Do Heal 52 Part III—How to Help 7 How to Help a Grieving Friend 63 8 Helping a Friend Cope with a Terminal Illness 73 9 How to Explain Death to a Child 82 10 Making the Funeral Arrangements 90 11 After the Funeral Is Ove 98 12 Preparing for Your Own Death 105 13 Questions and Answers about Death— 112 Can a Christian Commit Suicide? 112 What Happens to People between Death and the Resurrection? 113 Will We Know Each Other in Heaven? 114 Is Dying Painful? 115 What Happens to Babies after Death? 116 What Is Heaven Like? 117 Preface How to live! How to die! We all need to know how to do that. -

Cross-Examination: an Interrogation of Peter Rollins's Hermeneutic of The

EXT0010.1177/0014524613505261The Expository TimesReyburn 5052612013 Cross-examination: An interrogation of Peter Rollins’s hermeneutic of the crucifixion Duncan Reyburn University of Pretoria, South Africa Abstract This article, which is argumentative in nature, interrogates and critiques Peter Rollins’s hermeneutic of the crucifixion. This is done by calling into question Rollins’s reliance upon the writings of Slovenian dialectical materialist Slavoj Žižek, especially with regard to the focus on the cry of dereliction. It is argued, ultimately, that Rollins’s hermeneutic of the crucifixion contravenes the very co-ordinates that he has set up for his own theological-political project and argues for critically rethinking the way that otherness is conceived of in the hermeneutics of the emergent church milieu that Rollins is proposing. Keywords G. K. Chesterton, Crucifixion, Cry of dereliction, Doubt, Emerging Church, Faith, Hermeneutics, Peter Rollins, Slavoj Žižek “Is it possible then that Jesus himself not only beyond merely affirming labels. This is to say wanted Judas to betray him but actually that he is attempting to contribute to a kind of demanded it? … It is with such a reading in post-tribal, politically rather than doctrinally mind that the philosopher and cultural theorist motivated Christianity — an a/theistic Christianity Slavoj Žižek goes so far as write that, while ‘in that constantly calls its own dogmas into ques- all other religions, God demands that His tion. It is clear that Rollins’s project has some followers remain faithful to Him — only Christ asked his followers to betray Him in order to obviously positive aims, especially with regard to fulfil His mission” — Peter Rollins (2008:21). -

John D. Caputo CURRICULUM VITAE

John D. Caputo CURRICULUM VITAE EMPLOYMENT: Thomas J. Watson Professor of Religion and Humanities, Syracuse University, 2004– David R. Cook Professor Emeritus of Philosophy, Villanova University, 2004– David R. Cook Professor of Philosophy, Villanova University, 1993-2004 Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, Professor, Villanova University, 1968-2004 Visiting Professor, New School for Social Research, Spring, 1994 Distinguished Adjunct Professor, Fordham University Graduate Program, 1985-88 Visiting Professor, Fordham University, Fall, 1980 Visiting Professor, Duquesne University, Fall, 1978 Instructor, St. Joseph's University (Philadelphia, 1965-68) EDUCATION: Ph.D., 1968, Bryn Mawr College M.A., 1964, Villanova University B.A., 1962, La Salle University AWARDS Winner of the ForeWord Magazine Best Philosophy Book of 2007 award for What Would Jesus Deconstruct? 2008 Loyola Medal (Seattle University), 2007 American Academy of Religion Book Award for Excellence in Studies in Religion, “Constructive-Reflective Studies,” for The Weakness of God: A Theology of the Event (Indiana UP, 2007). 2004, Appointed Thomas J. Watson Professor of Religion and Humanities, Syracuse University; David R. Cook Professor Emeritus, Villanova University 1998, Choice Magazine, “Outstanding Academic Book Award” for Deconstruction in a Nutshell (Fordham UP, 1997) 1992, Appointed David R. Cook Professor of Philosophy 1991-92, National Endowment for the Humanities, Fellowship for College Teachers 1989, Phi Beta Kappa, Honorary Member, Villanova Chapter 1985, National Endowment for the Humanities, Summer Stipend 1983-84, American Council of Learned Societies, Fellowship 1982, Outstanding Faculty Scholar Award (V.U.) 1982, Summer Research Grant (V.U.) 1981, Distinguished Alumnus, V.U. Graduate School 1979-80, Phi Kappa Phi Honorary Society, Villanova University Chapter, President 1972, American Council of Learned Societies, Grant-in-aid (Summer grant) OFFICES Member, Book Awards Committee, American Academy of Religion, 2008-2009. -

Astrology and Truth: a Context in Contemporary Epistemology Downloaded from Cosmocritic.Com

Astrology and Truth: A Context in Contemporary Epistemology Garry Phillipson Supervised by: Nicholas Campion, Patrick Curry Submitted in partial fulfilment for the award of PhD University of Wales Trinity Saint David 2019 This is the final version of the text, as submitted for retention in the university’s Research Repository on 27th April 2020. Downloaded from Cosmocritic.com i ii Abstract This thesis discusses and gives philosophical context to claims regarding the truth-status of astrology – specifically, horoscopic astrology. These truth-claims, and reasons for them, are sourced from advocates and critics of astrology and are taken from extant literature and interviews recorded for the thesis. The three major theories of truth from contemporary Western epistemology are the primary structure used to establish philosophical context. These are: the correspondence, coherence, and pragmatic theories. Some alternatives are discussed in the process of evaluating the adequacy of the three theories. No estimation of astrology’s truth-status was found which could not be articulated by reference to the three. From this follows the working assumption that the three theories of truth suffice as a system of analysis with which to define and elucidate the issues that have arisen when astrology’s truth-status has been considered. A feature of recent discourse regarding astrology has been the argument that it should be considered a form of divination rather than as a potential science. The two accounts that embody these approaches – astrology-as-divination, and astrology-as-science – are central throughout the thesis. William James’s philosophy is discussed as a congenial context for astrology-as-divination. -

The Radical Emergent Christian Community of Ikon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Archivserver der Universitätsbibliothek Marburg Marburg Journal of Religion: Volume 15 (2010) ‘Inhabiting a space on the outer edges of religious life’: The Radical Emergent Christian Community of Ikon Stephen Hunt Abstract: What has come to be known as the ‘Emerging Church’ (or colloquially as the ‘emergents’) amounts to an innovating, if somewhat controversial contemporary Christian movement that attempts to be spiritually relevant in the contemporary cultural setting to both its adherents and those outside of its loosely demarcated boundaries. In this paper I overview one significant example of the movement’s more radical wing, the Belfast-based Ikon community in Northern Ireland.i The paper argues that, on the one hand, Ikon exemplifies the means by which a distinctly innovating and even intentionally provocative religious constituency endeavours to forge a juxtaposition within post- modernity. On the other, Ikon self-consciously attempts to avoid conforming to any typology and deliberately escape conceptualization, even underlining its own failures in what it aspires to be. The paper will indicate that the attempt to resist constricting characterizations is embedded in the very nature of the philosophical standpoints and theological leanings (such as they exist) embraced by the community as it seeks a unique but definitive Christian response to the challenges of post- modernity. Introduction The Emerging Church movement claims no one leadership formation, centralized authority or organisational structure, nor stipulates a coherent and over-arching aim or objective. For these reasons, and because of its radical and apparently embryonic nature, the ‘movement’ (itself an unsatisfactory designation) seemingly almost defies a succinct definition.